Abstract

Most pathologists assume that a diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) requires the finding of necrotizing vasculitis accompanied by granulomas with eosinophilic necrosis in the setting of asthma and eosinophilia. However, recent data indicate that this definition is too narrow and that adherence to it leads to cases of CSS being missed. CSS has an early, prevasculitic phase that is characterized by tissue infiltration by eosinophils without overt vasculitis. Tissue infiltration may take the form of a simple eosinophilia in any organ, and a fine-needle aspirate showing only eosinophils may suffice for the diagnosis in this situation. The prevasculitic phase appears to respond particularly well to steroids. Even in the vasculitic phase of CSS, many cases do not show a necrotizing vasculitis but often only an apparently nondestructive infiltration of vessel walls by eosinophils. In modern biopsy materials, granulomas frequently cannot be found. In the postvasculitic phase of CSS, healed vascular lesions resemble organized thrombi but typically show very extensive destruction of elastica and, often, an absence of eosinophils. The widespread use of steroids as therapy for asthma has led to the peculiar and confusing situation in which the steroid therapy accidentally suppresses CSS and changes in steroid treatment uncover the disease; this type of “formes frustes” CSS is now well recognized with leukotriene receptor antagonist treatment and will be seen with increasing frequency as other steroid-sparing therapies for asthma are introduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Historic Definitions of Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) as originally described (1) is a syndrome characterized by asthma, blood and tissue eosinophilia, and in its full-blown form, eosinophilic systemic vasculitis, along with necrotizing granulomas centered around necrotic eosinophils. However, experience with increasing numbers of cases indicates that this definition is too narrow. Many cases of CSS, especially the early (“prevasculitic” or “prodromal”) phase cases readily amenable to treatment, do not have overt vasculitis, but often have other, quite typical, patterns of organ involvement. As well, relatively new developments in diagnostic testing, notably ANCA, and new modes of treatment for asthma, have made it clear that a much broader definition is required for accurate diagnosis of CSS. Clinicians are becoming familiar with these findings, particularly the issue of CSS and leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy. However, few pathologists are aware of these issues and CSS appears to be underdiagnosed by pathologists.

The first description of CSS was made by Churg and Strauss in 1951 (1) on 13 patients (11 autopsied) under the title “allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and periarteritis nodosa.” Churg and Strauss emphasized the findings common to all cases: history of asthma; blood and tissue eosinophilia; necrotizing vasculitis; and a granulomatous response to eosinophilic necrosis (Table 1). Although the cases in the original description of CSS were remarkably similar, further experience has shown that exact definition of CSS is a problem, in part because CSS is very protean in its manifestations, a problem common to most forms of vasculitis, and in part because, as will be described, it has become clear that there is a sequence of events in the natural history of CSS and that some relatively early cases do not demonstrate vasculitis. As well, the original cases predated the use of exogenous steroids, and thus represent totally untreated disease. However, most asthmatics now are treated with steroids for their asthma, and this treatment, which is the preferred treatment for CSS as well, in itself changes the clinical appearances of CSS.

Current Definitions of CSS

Historically, pathologic descriptions of CSS were relatively few (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), in part because CSS is a rare disease (incidence on the order of 1–2 cases per million persons per year in the general population (6)). But the recognition that CSS could be successfully treated with steroids led, by the mid-1980s, to a shift in emphasis from purely pathologic diagnosis to clinical diagnosis (7). Unfortunately, clinical diagnosis is also not simple, and thus a variety of definitions exist in the literature as shown in Table 1. The original Churg and Strauss definition (1), the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definition (8), and the Lanham et al. (7) criteria require overt vasculitis, although Lanham et al. (5, 7) also stress the idea of an early, prevasculitic phase of the disease (see below). The broadest definition is that of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR; 9), which is notionally based on subclassifying patients thought to have clinical vasculitis but does not actually require pathologic evidence of vasculitis. The ACR criteria instead allow tissue eosinophilia in the absence of pathologic vasculitis to serve as one criterion for the diagnosis of CSS. Both the ACR and the Lanham criteria also emphasize allergic rhinitis as a part of CSS.

These definitions also predate the widespread use of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) testing, and ANCA status is not part of any of these diagnostic schemes. CSS is associated with a positive ANCA in some reports in as many as 70% of cases (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15); this is usually p- (myeloperoxidase) ANCA, although c-ANCA–positive patients have also been reported, and sometimes the proportion of positive cases is much smaller (see Reference 11). Microscopic polyangiitis, one of the morphologic differentials of CSS, is also typically p-ANCA positive in about 40–80% of cases, whereas Wegener's granulomatosis, another morphologic differential, is generally c- (proteinase 3) ANCA positive, in some studies in up to 90% of cases (11, 12, 13, 14, 15). There appears to be a consensus that a properly performed ANCA test, which must include an ELISA to show proteinase 3 or myeloperoxidase specificity, provides strong support for a diagnosis of CSS, even if overt vasculitis cannot be found.

Natural History of CSS

The early (“prodromal,” “prevasculitic”) phase

Although the original cases of CSS all had florid vasculitis, it has become apparent from clinical observations (3, 5, 7) that many cases pass through a series of stages before the development of vasculitis and that identification of patients in the early phase is important because they appear to respond well to steroids and to have an excellent prognosis (Table 2).

The idea of a natural history of CSS was introduced by Lanham et al. (7). They summarized 138 cases in the literature and 16 of their own and suggested that the typical sequence of events is, first, the appearance of clinically overt allergic rhinitis (mean age of appearance, 28 years), followed several years later by the development of asthma (mean age of appearance, 35 years), and, finally, the development of vasculitis (mean age of appearance, 38 years). Before vasculitis appears, there is often clinically apparent infiltration of tissues by eosinophils (3), and it is this pathologic tissue eosinophilia that is the diagnostic hallmark of early-stage CSS. This sequence is by no means invariable, and all manifestations may occur together; as well, some patients do not have clinical allergic rhinitis, and in rare cases asthma develops after vasculitis (16).

Allergic rhinitis was believed to be, in retrospect, the earliest manifestation of CSS in about 70% of the cases summarized by Lanham et al. (7) and in 60% of the cases of Guillevin et al. (16). The rhinitis is often severe and may require repeated nasal polypectomies to relieve obstruction and sinusitis. As the disease advances, many patients develop asthma that is increasingly difficult to control, and this is part of early-stage disease (3, 5, 7), although obviously by themselves neither asthma nor allergic rhinitis is specific for nor diagnostic of CSS.

Blood eosinophilia is found at some time in almost all patients with CSS, but may be suppressed by steroid therapy. Lanham et al. (7) suggested that eosinophilia more than 1.5 × 109/L (at some point) is a required feature for diagnosis. Care should be taken not to confuse the eosinophilia of CSS, which is often quite marked, with the low-level eosinophilia (less than 1.0 × 109) sometimes found in otherwise healthy asthmatics. Of note, blood eosinophilia may revert to normal or near-normal values in CSS, but tissue infiltration by eosinophils can still be present (5, 7).

The characteristic feature of the early phase of CSS is extravascular tissue infiltration by eosinophils, and this condition is, in my experience, underrecognized by pathologists, not in the sense of morphology, but in the sense of indicating to the clinician the significance of eosinophils as a confirmatory diagnostic finding. Extravascular tissue infiltration by eosinophils may occur in any organ. In the lung, this event frequently takes the form of the dense peripheral radiographic airspace infiltrates of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (Fig. 1) and often is accompanied by fever and weight loss. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis may present with abdominal pain, bleeding, diarrhea, or obstruction. Eosinophilic lymphadenitis can cause enlarged lymph nodes, and I have seen the same phenomenon in a salivary gland (Fig. 1). Myalgias and arthralgias may be present in the early stage and may reflect eosinophilic tissue infiltration.

Early (prevasculitic) phase CSS. (A) CT scan showing enlarged parotid (arrow) in a patient with asthma and eosinophilia. A fine needle aspirate showed only eosinophils, a finding that, in this setting, strongly supports a diagnosis of early phase CSS. In this particular case the chest CT showed dense peripheral airspace infiltrates consistent with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (B). Open lung biopsy demonstrated a typical histologic picture of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia with areas of necrosis (top of field in D) but without evidence of vasculitis (C,D). BOOP-like areas (E) were also present; BOOP is a common finding in CEPof any cause. Despite the clinical and pathologic absence of vasculitis, the patient was p-ANCA positive, a finding that here is confirmatory of CSS. (C,D,E: H and E × 160)

Pathologic specimens may be obtained in early-stage CSS because the disease is suspected clinically or because there is unexplained organ enlargement or dysfunction of uncertain etiology. The most important issues for the pathologist in this setting are the following: 1) to show the presence of eosinophilic tissue infiltration; 2) to document the presence or absence of vasculitis because this may affect therapy; and 3) to communicate to the clinician the extent to which these findings (and those of ANCA testing as well) can be used to support a diagnosis of CSS.

In regard to tissue eosinophilia, a perfectly acceptable result may be obtained by fine needle aspiration of an accessible organ. For example, Figure 1 shows a patient with asthma and eosinophilia who developed salivary gland enlargement. The initial diagnostic test was a fine-needle aspirate of the salivary gland. This showed only eosinophils. In this clinical setting, the finding of eosinophilic infiltration is sufficient to suggest the diagnosis of CSS. This particular patient also had chronic eosinophilic pneumonia documented on a subsequent biopsy (Fig. 1) and a positive pANCA, although there was no clinical or pathologic evidence of vasculitis.

Pulmonary eosinophilia may, similarly, be documented by bronchoalveolar lavage, but a high percentage of eosinophils is required to support a diagnosis of CSS, because small numbers of eosinophils are common in lavages from asthmatics. The nasal polyps of CSS are histologically similar to those seen in patients without CSS. Heavy eosinophilic infiltrates are the rule, but vasculitis is very rare. However, because nasal polyps of any cause may contain eosinophils, polyps are not generally suitable specimens for diagnosing early-stage CSS.

Up to 70% (5, 7, 16) of cases of CSS have pulmonary infiltrates at some point in their course, and thus lungs are often biopsied. In the early stage of CSS, the histology may be indistinguishable from ordinary chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP; Fig. 1). Foci of eosinophil necrosis and scattered giant cells may be observed: these are not specific, and can be seen in ordinary CEP (17) as well as in CSS. CEP-like foci in CSS may appear to have few or even no eosinophils if the patient has been treated with high-dose steroids, and steroids will produce eosinophil necrosis in CEP type lesions of any cause.

Clinically a radiographic picture of CEP appears to be accepted as a legitimate finding in CSS (18), and there are several reports in the literature identifying chronic eosinophilic pneumonia as a presenting feature of CSS, in one instance eight years before the vasculitic stage developed (19, 20). On careful reading, these reports describe what appears to be prevasculitic stage CSS.

Thus, in a setting clinically suspicious for CSS, the finding of a picture of CEP provides support for that diagnosis. However, the differential diagnosis of asthma, eosinophilia, and histologic CEP must be considered. One major differential is allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Such patients have asthma and eosinophilia, along with serum precipitins against Aspergillus (rarely other) organisms. They usually show a variety of pulmonary changes including central bronchiectasis, mucoid impaction, eosinophilic pneumonia, and necrotizing bronchiolitis/bronchocentric granulomatosis as well as small numbers of Aspergillus organisms in the tissues (21). They do not have evidence of systemic vasculitic disease, and in most cases, the morphologic findings and the chest radiographic findings are quite different from those of CSS. A single case of CSS in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis has been reported (22).

If one subtracts out the patients with CSS or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, some patients with asthma, eosinophilia, and histologic CEP have true CEP, but it is difficult to determine how often this happens. Fox and Seed (23) summarized 63 cases of CEP in the literature and reported that 53% had asthma. Of note, 70% had asthma for less than 5 years before the appearance of CEP, a temporal pattern also frequent in CSS. Similarly Marchand et al. (24) reviewed 62 more recent cases of CEP and found that 52% had asthma, often severe. Some series of cases of CEP contain patients whose stories lead the clinician to strongly suspect CSS. For example, in Case 7 of the Carrington series (25), the patient developed sudden unexplained heart failure, and the authors speculated about the presence of vasculitis, but eosinophilic myocarditis, a common finding in CSS, would provide an equally good explanation. In the series of Marchand et al. (24), several patients had nonnecrotizing vasculitis on biopsy, one was pANCA positive, one had pericarditis, and one had purpura. These findings support the idea that some proportion of cases reported as CEP may really be CSS, and, of course, such patients might eventually develop vasculitic phase CSS if left untreated. However, given that both CSS and CEP are usually treated with high-dose steroids, the distinction may not be crucial.

Radiographic infiltrates and blood eosinophilia may be seen in a variety of parasitic infections including Strongyloides, Ascaris, Toxocara, and Ancyclostoma in North America (26, 27). However, these patients are typically not asthmatic, although they may wheeze temporarily when the lung is showered with parasites. Similarly, their chest radiographs usually show no lesions or fleeting airspace infiltrates. Marked eosinophilia may also be seen in tropical eosinophilia (occult filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi; 26, 27). Again, these patients are typically not asthmatic and most in fact have restrictive functional abnormalities. Their chest radiographs typically show increased interstitial markings. Organisms may be seen in the lung on biopsy with any of these infections, and occasionally, CEP-like foci are present as well (28). Eosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates may also be seen in drug reactions, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and occasionally in fungal and tuberculous infections (27). Usually, such patients are not asthmatic.

In early CSS, diagnostic gastrointestinal biopsies from any site will show an intense eosinophil infiltrate. Care must be taken not to overinterpret GI biopsies; small numbers of eosinophils are common in normals. Biopsy of other accessible organs such as enlarged lymph nodes may show only eosinophil infiltration without any other specific findings.

Last, it should be remembered that the clinician requesting a biopsy probably expects a diagnosis of vasculitis to confirm his or her impression of CSS. By definition, vasculitis is absent in specimens from early-stage disease, and this absence should be noted along with a comment about whether the findings that are present (for example, tissue eosinophilia) are consistent with early-stage CSS. There is a distinct tendency, in my experience, toward underdiagnosing CSS in this situation, with a consequent delay in appropriate therapy.

The vasculitic phase

The distinction between early-phase and vasculitic-phase disease may be subtle. Any of the pathologic features seen in early-stage CSS may also be seen in the vasculitic phase, and eosinophilic tissue infiltration is almost always present. However, the classic histologic hallmarks of the vasculitic phase are (1) an eosinophil rich necrotizing vasculitis involving primarily small arteries, arterioles, venules, and veins and (2) necrotizing granulomas centered on necrotic eosinophils (Figure 2). What is not widely appreciated is how infrequently all of the classic findings are actually found in modern biopsy material; in a recent series of 23 patients, Reid et al. (29) were able to show the original Churg and Strauss criteria in only 4!

Vasculitic phase CSS in kidney. A, note the necrotizing granuloma in the upper part of the field and the necrotizing vasculitis in the lower part of the field, both superimposed on a background of eosinophilic inflammation in a patient with asthma and eosinophilia. Although described as the classic picture of CSS, in modern biopsy material this combination of features, either in a single site, or merely scattered in different areas of the biopsy, is actually uncommon. B, another small vessel showing fibrinoid necrosis. (A: H and E, 200 ×; B: H and E, 400 ×)

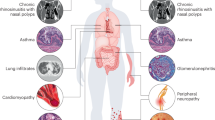

CSS is a systemic vasculitis, and any organ may be affected (Table 3; Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). The vasculitis shows a wide variety of appearances. Necrotizing vasculitis (Fig. 2) can affect any small vessel and consists of infiltration of the wall by inflammatory cells, mostly eosinophils, but sometimes with a proportion of PMN; where this is marked, the vessel wall becomes necrotic and may be replaced by granular pink material somewhat resembling fibrin, so-called fibrinoid necrosis (Fig. 2B). However, in many instances, the vasculitis of CSS consists only of infiltration of the vascular wall by inflammatory cells without any obvious tissue necrosis; in other words, nonnecrotizing vasculitis (Figs. 3 and 6). This finding is commonly seen in venules and small veins, and in my experience, it is particularly frequent in the lung. In the recent large series of Guillevin et al. (16), 48% of muscle biopsies, 63% of nerve biopsies, and 67% of skin biopsies were positive for vasculitis, but necrotizing vasculitis was found in only 33–50% of these specimens. Thus the absence of necrosis in the vessel wall in no way mitigates against the diagnosis. As well, biopsy or autopsy material may be obtained from patients treated with steroids (see below), and steroids can rapidly and often totally suppress eosinophil infiltration. Therefore, in occasional cases, the pathologic picture is one of a small vessel vasculitis without eosinophils, and clinical information is crucial to the correct diagnosis.

Nonnecrotizing vasculitis in CSS. A, a small pulmonary vessel demonstrates extensive eosinophilic infiltration of the wall, but the higher power view (B) indicates that the vascular structure is preserved. Apart from vasculitis, the lung parenchyma had the appearance of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. (H and E; A, 160 ×; B, 400 ×)

Eosinophilic myocarditis in CSS. Myocarditis appears to be invariably seen in the vasculitic rather than prevasculitic phase (compare Fig. 2 from the same case). This is one of the Formes Frustes patients described by Churg et al. (33). The patient had been self-treated with very high dose steroids to control his asthma; when steroids were discontinued because of steroid-induced myopathy, overt vasculitis appeared. He died of cardiac failure (H and E, 200 ×).

CSS granulomas consist of necrotic eosinophils and Charcot-Leyden crystals, usually with a surrounding palisade of giant cells or epithelioid histiocytes (Fig. 2). Churg and Strauss originally called them “allergic granulomas.” In CSS granulomas, the necrotic material is usually distinctly pink on H and E stains, in contrast to the usual finding in Wegener's granulomatosis, where the necrotic material is derived from PMNs and is typically hematoxyphilic (3); this distinction can be diagnostically helpful in equivocal cases. In the original description of Churg and Strauss (1), CSS granulomas were reported in 100% of autopsy cases, and this finding has lead to the idea that they are required for diagnosis. However, in more modern studies, they are much less frequent, perhaps because the volume of tissue available is much smaller in biopsies, or because they are suppressed by steroid therapy. Granulomas are not required for the diagnosis of CSS, and the absence of granulomas should not influence the pathologist against a diagnosis of CSS.

The vasculitis of CSS may also affect capillaries and small venules, and occasionally only vessels of this size are affected. In the skin, this process appears as leukocytoclastic vasculitis with an accompanying eosinophilic infiltrate and sometimes with polymorphonuclear leukocytes as well (Fig. 5), and in the lung as capillaritis, an underrecognized form of vasculitis associated with alveolar hemorrhage (16, 30, 31). In the large series of Guillevin et al. (16), alveolar hemorrhage was diagnosed in only 3 of 96 patients. However, a recent study (32) of lavage fluid in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis and CSS showed large numbers of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in more than 50% of cases, implying that subclinical alveolar hemorrhage is actually quite common in these conditions. Patients with capillaritis can have massive, sometimes fatal, hemoptysis, and thus careful examination of lung biopsies for evidence of capillaritis should be carried out routinely in suspected CSS cases.

The postvasculitic phase

In successfully treated patients, the disease enters the postvasculitic phase (3, 5, 7). Asthma and allergic rhinitis are still present, but there is no active vasculitis, although persisting neuropathy and hypertension may be seen. Microscopically, the only specific finding is usually the presence of healed vasculitis. This takes the form of thrombosed small vessels. The thrombi are usually well organized by the time of pathological sampling (Fig. 7) but can often be distinguished from ordinary thromboemboli by the loss of large portions of the vessel elastica (Fig. 7), an uncommon event with ordinary emboli. Eosinophils may not be present if disease has regressed or is being held in check by steroid therapy. In this situation, the meaning of the morphology depends on the clinical history: similar findings could well be seen in treated microscopic polyangiitis and Wegener's granulomatosis.

Disease Unmasked by Manipulating Steroid Therapy: Formes Frustes of CSS

In many cases, CSS responds well to steroid therapy. However, steroids are also widely used to treat asthma itself. Thus some patients develop CSS, but the disease is more or less completely, and accidentally, suppressed by steroid therapy for the underlying asthma, only to appear in clinically recognizable form if steroid therapy is discontinued or manipulated.

This sequence of events has been the source of some debate in the literature. In 1995 we (33) described four such patients and labeled them “Formes Frustes of CSS” to indicate that the disease was hidden or incompletely visible until unmasked by changes in steroid therapy. Three of these patients had severe enough asthma to require systemic steroids, but the fourth was using only inhaled steroids. Clinically, the findings ranged from early disease with asthma, eosinophilia, and cervical lymph node enlargement (biopsy showed an eosinophilic lymphadenitis) to severe vasculitis and granuloma formation with death from cardiac failure (see Fig. 2, taken from one of the original cases). Other series of such cases have now been reported (34), including cases where the only change was a switch from systemic to inhaled steroids (35). Apart from the association with changes in steroid therapy, the original formes frustes cases and the subsequent ones all appear to be clinically typical CSS with both early and vasculitic phase disease observed. The pathologic findings also appear to be similar to those in ordinary CSS, albeit the number of biopsy samples available is limited and no formal comparative studies have been done.

Over the past few years, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) therapy for asthma has been introduced; the two most commonly used drugs, zafirlukast and montelukast, are selective antagonists of the Type 1 cysteinyl leukotriene receptor (36). One of the benefits of LRA therapy is that in many instances, it allows tapering or discontinuing of steroid therapy. Within a few months of LRA coming on the market, cases now recognized as CSS began to appear. Initially, Wechsler reported eight such patients who had been taking zafirlukast (37) and raised the question of whether this was a toxic drug effect (38, 39). Similar findings followed shortly when montelukast was introduced (38, 39). However, careful review of the data, including careful comparisons of incidence rates in asthmatics, has led to the conclusion that these are all cases of CSS unmasked by decreasing steroid use (38, 39, 40, 41, 42); that is, represent formes frustes disease. Because most new asthma therapies are likely to be steroid sparing, it is likely that further cases will appear as each agent is introduced, and the pathologist should be aware of this phenomenon.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CSS fundamentally includes two separate categories: diseases characterized by tissue (largely pulmonary) eosinophilia (discussed above) and other forms of ANCA-positive small-vessel vasculitis (Table 4). To a certain extent, the separation among the various forms of ANCA-positive vasculitis is not crucial, since treatment is, in broad outline, the same, although many cases of CSS can be treated with steroids alone, as opposed to microscopic polyangiitis and Wegener's granulomatosis, which usually require both steroids and cyclophosphamide.

Therapy and Prognosis

Systemic steroids at high doses are the usual initial therapy for CSS. In cases that fail to respond to steroids, or that have life-threatening complications, for example, progressive renal failure, and probably in all cases that have cardiac involvement, or that have complications associated with extensive morbidity such as neuropathy with vasculitis, cyclophosphamide may be added (7, 16), Early (prevasculitic) phase disease appears to respond much more quickly and completely than vasculitic disease (7, 16). Systemic vasculitides of this type can progress rapidly, and some argue that on this basis, the vasculitic phase should always be treated with both steroids and cyclophosphamide (5). The role of serum ANCA in monitoring disease activity is presently a controversial topic (11, 12, 13, 14, 15).

CONCLUSION

Even in the modern era, it is clear that a significant fraction of patients in the vasculitic phase do not respond to therapy, a point that emphasizes the need for accurate and early diagnosis, preferably in the prevasculitic phase. Guillevin et al. (16) reported that of 96 patients, 8.5% failed to achieve remission, and 26% had at least one relapse. In their series, cardiac involvement or serious gastrointestinal involvement such as bowel infarction were particularly associated with mortality. Their 78-month survival was 72%. In the slightly older collected series of cases from Lanham et al. (7), approximately half of the deaths were associated with cardiac disease. It is of interest that in a large series comparing CSS and microscopic polyarteritis, both diseases had about the same overall prognosis, although the causes of death were different (43).

References

Churg J, Strauss L . Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol 1951; 27: 277–301.

Chumbley LC, Harrison EG Jr, De Remee RE . Allergic granulomatosis and angiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome). Mayo Clin Proc 1977; 52: 477–484.

Churg J . Churg-Strauss syndrome.In: Thurlbeck WM, Churg A, editors. Pathology of the lung. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1995.p. 425–435.

Koss MN, Antonovych T, Hochholtzer L . Allergic granulomatosis (Churg-Strauss syndrome). Am J Surg Pathol 1981; 5: 21–28.

Lanham JG, Churg J . Churg-Strauss syndrome.In: Churg A, Churg J, editors. Systemic vasculitides. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1991.pp. 101–120.

Watts RA, Carruthers DM, Scott DG . Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: changing incidence or definition? Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995; 25: 28–34.

Lanham JG, Elkon KB, Pusey CD, Hughes GRV . Systemic vasculitis with asthma and eosinophilia: A clinical approach to the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1984; 63: 65–81.

Jennette JC, Flak RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Hunder GG, Kallenberg CG . Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37: 187–192.

Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, Michel A, Bloch DA, Arend WP, Clabrese LH, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY, Lightfoot RW, McShane DJ, Mills JA, Stevens MB, Wallace SL, Zvaifler NJ . The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 1094–1100.

Guillevin L, Visser H, Noel LH, Pourrat J, Vernier I, Gayraud M, Oksman F, Lesaave P . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in systemic polyarteritis nodosa with and without hepatitis B infection and Churg-Strauss syndrome—62 patients. J Rheum 1993; 20: 1345–1349.

Hoffman GS, Specks U . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41: 1521–1537.

Gross WL, Csernok E, Helmchen U . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies, autoantigens, and systemic vasculitis. APMIS 1995; 103: 81–97.

Homer RJ . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as markers for systemic autoimmune disease. Clin Chest Med 1998; 19: 627–639.

Kallenberg CGM, Tervaert JWC . What is new with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: diagnostic pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1999; 8: 307–315.

Kyndt X, Reumaux D, Bridoux F, Tribout B, Bataille P, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Duthilleul P, Vanhille P . Serial measurements of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in patients with systemic vasculitis. Am J Med 1999; 106: 527–533.

Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Casassus P . Churg-Strauss syndrome. Clinical study and long-term follow-up of 96patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78: 26–37.

Colby TV, Carrington CB . Interstitial lung disease.In: Thurlbeck WM, Churg A, editors. Pathology of the lung. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1995.p. 668.

Choi YH, Im JG, Han BK, Kim JH, Lee KY, Myoung NH . Thoracic manifestation of Churg-Strauss syndrome: radiologic and clinical findings. Chest 2000; 117: 117–124.

Golstein MA, Steinfeld S . Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia followed by Churg-Strauss syndrome. Rev Rheum 1996; 6: 624–628.

Hueto-Perez-de-Heredia JJ, Dominguez-del-Valle FJ, Garcia E, Gomex ML, Gallego J . Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia as a presenting feature of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Eur Respir J 1994; 7: 1006–1008.

Katzenstein A–L A . Immunologic lung disease.In: Katzenstein and Askin's surgical pathology of non-neoplastic lung disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997.p. 138–166.

Stephens M, Reynolds S, Gibbs AR, Davies B . Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis progressing to allergic granulomatosis and angiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome). Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 37: 1226–1228.

Fox B, Seed WA . Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Thorax 1980; 5: 570–580.

Marchand E, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Lauque D, Duriew J, Tonnel AB, Cordier JF . Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1998; 77: 299–312.

Carrington CB, Addington WW, Goff AM, Madoff IM, Marks A, Schwaber JR, Gaensler EA . Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1969; 280: 787–798.

Petersen C, Mills J . Parasitic infections.In: Murry JF, Nadel JA, editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994.p. 1201–1244.

Allen JN, Davis WB . Eosinophilic lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 150: 1423–1438.

Udwadia FE, Josahi VV . A study of tropical eosinophilia. Thorax 1964; 19: 548–556.

Reid AJ, Harrison BD, Watts RA, Watkin SW, McCann BG, Scott DG . Churg-Strauss syndrome in a district hospital. QJM 1998; 91: 219–229.

Clutterbuck EJ, Pusey CD . Severe alveolar haemorrhage in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Eur J Respir Dis 1987; 71: 158–163.

Lai RS, Lin SL, Lai NS, Lee PC . Churg-Strauss syndrome presenting with pulmonary capillaritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Scand J Rheumatol 1998; 27: 230–232.

Schnabel A, Reuter M, Csernok E, Richter C, Gross WL . Subclinical alveolar bleeding in pulmonary vasculitides: correlation with indices of disease activity. Eur Respir J 1999; 14: 118–124.

Churg A, Brallas M, Stephen R, Cronin MD, Churg J . Formes frustes of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Chest 1995; 320–323.

Bili A, Condemi JJ, Bottone SM, Ryan CK . Seven cases of complete and incomplete forms of Churg-Strauss syndrome not related to leukotriene receptor antagonists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 104: 1060–1065.

Le Gall C, Pham S, Vignes S, Garcia G, Nunes H, Fichet D, Simonneau G, Duroux P, Humbert M . Inhaled cortocosteroids and Churg-Strauss syndrome: a report of five cases. Eur Respir J 2000; 15: 978–981.

Lipworth BJ . Leukotriene-receptor antagonists. Lancet 1999; 353: 57–62.

Wechsler ME, Garpestad E, Flier SR, Kocher O, Weiland DA, Polito AJ, Klinek MM, Bigby TD, Wong GA, Helmers RA, Drazen JM . Pulmonary infiltrates, eosinophilia, and cardiomyopathy following corticosteroid withdrawal in patients with asthma receiving Zafirlukast. JAMA 1998; 279: 455–457.

Wechsler ME, Pauwels R, Drazen JM . Leukotriene modifiers and Churg-Strauss syndrome: adverse effect or response to corticosteroid withdrawal? Drug Saf 1999; 21: 241–251.

Wechsler ME, Finn D, Gunawardena D, Westlake R, Barker A, Haranath SP, Pauwels RA, Kips JC, Drazen JM . Churg-Strauss syndrome in patients receiving montelukast as treatment for asthma. Chest 2000; 117: 708–713.

Churg A, Churg J . Steroids and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Lancet 1998; 352: 32–33.

Churg A, Churg J . Zafirlukast and Churg-Strauss syndrome. JAMA 1998; 279: 1949–1950.

Martin RM, Wilton LV, Mann RD . Prevalence of Churg-Strauss syndrome, vasculitis, eosinophilia and associated conditions: retrospective analysis of 58 prescription-event monitoring cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1999; 8: 179–189.

Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, Cohen P, Jarrousse B, Lortholary O, Thibult N, Casassus P . Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996; 75: 17–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Churg, A. Recent Advances in the Diagnosis of Churg-Strauss Syndrome. Mod Pathol 14, 1284–1293 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880475

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880475

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Long-term mepolizumab treatment reduces relapse rates in super-responders with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology (2023)

-

Eosinophile Granulomatose mit Polyangiitis (EGPA)

rheuma plus (2023)

-

Eosinophile Granulomatose und Polyangiitis – Diagnostik und Therapie

Der Pneumologe (2018)

-

Necrotizing eosinophilic granulomatous lymphadenitis with ring- and C-shaped granulomas—an underrecognized specific manifestation of nodal Churg-Strauss syndrome

Journal of Hematopathology (2017)