Abstract

The cases of two patients with Stage IE primary cutaneous T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL) are described. In both, the lesion showed a dense infiltrate by numerous small T lymphocytes with scattered histiocytes and large atypical B-lymphoid cells. Polymerase chain reaction assays demonstrated that the B cells were monoclonal, with immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement. No clonal rearrangements of the T-cell receptor gamma gene were observed. Both patients were disease-free at 4 months and at 5 years after therapy, respectively. Although rare, primary cutaneous T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma appears to have a better prognosis than its nodal counterpart, with or without skin involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL) was initially proposed in 1988 to describe a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder in which the majority of the cells are reactive T lymphocytes, with the large neoplastic B cells accounting for <15% of the overall infiltrating lymphoid cells (1). It is a rare entity, accounting for approximately 1–2% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and is generally believed to be a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the Revised European-American Lymphoma classification and the upcoming World Health Organization classification. A variant form of TCRBCL, histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma, was described by Delabie et al. (2); it is characterized by a prominent reactive histiocytic infiltrate. The neoplastic B cells are clonal based on results from immunohistochemical and/or immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement studies.

TCRBCL has both nodal and extranodal presentation. Nodal TCRBCL with or without cutaneous involvement is an aggressive lymphoma that often presents as Stage IV disease, with frequent bone marrow involvement, and requires systemic chemotherapy (3, 4, 5). However, the clinical behavior of the extranodal counterparts, particularly the primary cutaneous one, is unclear for several reasons. First, primary cutaneous TCRBCL is so rare that only a handful of cases have been reported in the literature (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Second, TCRBCL in general is frequently misdiagnosed as pseudolymphoma, pleomorphic peripheral T-cell lymphoma, or lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (1, 3, 5, 8). In this report, we describe two cases of primary cutaneous TCRBCL and review the salient histologic as well as clinical features of this rare entity.

CASE REPORT

The first patient was a 51-year-old white man with no relevant medical history who presented to an outside plastic surgeon for a small lesion on the upper lip near the base of the right naris. The lesion was noted by the patient to have grown slowly during the last several months. He was feeling fine without fever, night sweat, weight loss, or other symptoms. At physical examination, the lesion was <1 cm in maximal dimension. No other skin lesions were observed. There was no evidence of peripheral lymphadenopathy. Clinically, the lesion was thought to be a basal cell carcinoma and was excised.

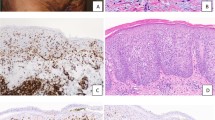

Histologically, the lesion showed a dense polymorphous lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissue. The majority of the cells were small and mature appearing, with a few admixed large, atypical cells (Fig. 1, A–B). The epidermis was unremarkable. By immunoperoxidase staining, the small lymphocytes, which accounted for more than 90% of the lymphocytes, were CD3+ T cells, whereas the scattered, large, atypical lymphocytes were CD20+ B cells (Fig. 2, A–B). Immunostains for kappa and lambda light chains were noncontributory, and in situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus mRNA was negative. A polymerase chain reaction assay using degenerate consensus primers to amplify across the variable and joining region junction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene generated a distinct product (Fig. 3A), demonstrating that the small number of large, atypical B cells were clonal. The T cells showed no evidence of clonal rearrangement of their T-cell receptor gamma gene by polymerase chain reaction assay (data not shown).

Detection of clonal immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement by polymerase chain reaction using consensus primers for the variable (5′-ACA-GGG-C(C/T)(G/C)-TGT-ATT-ACT-GTG-3′) and the joining (5′-GTG-ACC-AGG-GTN-CCT-TGG-CCC-CAG-3′) regions of the gene. Arrow (A) and arrowhead (B) indicate the clonally rearranged products amplified from DNAs of the first and the second patients’ skin biopsies, respectively.

Subsequent chest and abdominal computed tomography scans showed no evidence of visceral lymphadenopathy. A bone marrow biopsy was negative for lymphoma involvement. Complete blood count and other chemical analyses including lactate dehydrogenase level were within normal range. A diagnosis of Stage IE T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma arising from the upper lip was made. The patient received three cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone plus involved field radiation (3600 cGy). He is symptom- and disease-free 4 months after treatment.

The second patient was a 62-year-old white man who presented to an outside hospital in March 1994 with a subcutaneous nodule in his scalp. No other cutaneous lesions or lymphadenopathy were noted during physical examination.

The histologic appearance of the scalp lesion was similar to that seen in the first patient (not shown). A PCR assay for the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene revealed a single prominent product (Fig. 3B), demonstrating the monoclonal nature of the large transformed B cells in this lesion. There was no evidence of clonal T-cell receptor gamma gene rearrangement. Extensive staging at the time of lymphoma diagnosis failed to reveal visceral lymphadenopathy or bone marrow involvement. After excision, the patient received radiation therapy to the involved field in the scalp (a total of 5940 cGy). In December 1995, a repeat bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a normocellular marrow with focal granulomatous reaction. A liver biopsy at the same time showed a similar granulomatous process. In both biopsy specimens, organisms morphologically compatible with Histoplasma capsulatum were identified by special silver staining. It was thought that in both liver and bone marrow, the granulomas were secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis, and the patient was treated accordingly. Multiple follow-up bone marrow biopsies and magnetic resonance–imaging examinations thereafter showed no evidence of systemic lymphoma. He is disease-free 5 and a half years after the initial diagnosis of Stage IE primary cutaneous TCRBCL.

DISCUSSION

Primary cutaneous TCRBCL is a rare lymphoma. Until now, only 16 cases (including the ones we have described here) have been described in the literature (Table 1). Most patients were men (M:F = 13:3). Their ages ranged from 30 to 87 years, with an average age of 57.6 years at the time of lymphoma diagnosis. In the majority of cases, the lesion was located in the head, arms, or trunk. Most patients had Stage IE disease with lesions confined to the skin. The treatment modalities varied from no treatment to combined radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Except for two patients who died of diseases unrelated to their primary cutaneous TCRBCL, all the remaining patients were alive and well within the period of follow-up.

Histologically, the lymphoid infiltrate in the skin is composed of a mixture of small lymphocytes, some with irregular nuclear contours, epithelioid histiocytes, plasma cells, and sparse individual large lymphoid cells accounting for <15% of the infiltrating cells. The epidermis is usually spared. The large atypical lymphoid cells sometimes have clear cytoplasm and multilobated nuclei. But typical Reed-Sternberg cells are not seen. Frequently, prominent vascular proliferation is present. The histologic appearance mimics that seen in pleomorphic peripheral T-cell lymphoma or Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but the large atypical lymphoid cells are positive for B-cell markers, whereas the background small lymphocytes are reactive T cells on immunohistochemical stain, and the large B cells are always negative for CD15 and CD30. Lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma may be more difficult to distinguish histologically, though cutaneous involvement by this disease is exceedingly rare. In addition, the clonality of the large B cells can usually be demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining for immunoglobulin light-chain protein and/or molecular genetic study for rearrangement of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene.

Numerous studies have documented that primary cutaneous lymphomas often have different clinicopathologic features compared with primary nodal lymphoma of the same histologic subtype, with or without secondary skin involvement. For example, primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma lacks epithelial membrane antigen expression and shows no evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection. The t(2;5) translocation and the resultant expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase are consistently absent in primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. In noncutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cases expressing anaplastic lymphoma kinase have a better prognosis than those not expressing anaplastic lymphoma kinase. However, primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma has an excellent prognosis, with an estimated 5-year survival of >90% (14, 15). Therefore, correct diagnosis and appropriate staging of primary cutaneous lymphomas are essential to avoid unnecessarily aggressive treatment.

Although the histologic appearance of primary cutaneous TCRBCL is similar to its nodal counterpart, the clinical behavior is drastically different. Nodal TCRBCL with or without secondary skin involvement usually presents as advanced-stage disease, with frequent bone marrow involvement and splenomegaly. Despite aggressive treatment with combination chemotherapy, the overall survival rate at 3 years in general is <50% (3, 4, 5). The reported cases of primary cutaneous TCRBCL appear to have a better prognosis. Although the follow-up was relatively short (from 2 months to 13 years, with an average of about 2 years; Table 1), most patients were alive and well without disease during that time. Only two patients died of unrelated diseases, one with residual lymphoma and one without residual lymphoma. Interestingly, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma reported by Yang et al. (16) also had an excellent prognosis. Nodal TCRBCL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are considered to represent a spectrum of disease. It may be that primary cutaneous TCRBCL and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma represent a spectrum of disease, with both showing better outcome than their systemic counterparts.

The massive T-cell infiltration in TCRBCL is probably related to the cytokine milieu of the tumor, such as interleukin-4 (17). It has also been hypothesized that Epstein-Barr virus might participate in the pathogenesis of the B-cell lymphoma, with a corresponding T-cell reaction (18, 19). However, evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection has only been documented in a few cases of nodal TCRBCL and in only one case of primary cutaneous TCRBCL (8). In both cases described here, there was no evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Although the pathogenesis is not completely understood, it has been suggested that the neoplastic B cells are germinal center B cells in origin (20).

In conclusion, the unusual good prognosis of primary cutaneous TCRBCL compared with its nodal counterpart is exactly analogous to what has been seen with other types of histologically aggressive lymphomas, including CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Though more cases need to be studied to further characterize this entity, if true, our findings further support the notion that the skin is a special site of involvement for lymphomas of many types and that the usual adverse histologic features may not necessarily predict poor outcome in cutaneous lesions.

References

Ramsay AD, Smith WJ, Isaacson PG . T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1988; 12: 433–443.

Delabie J, Vandenberghe E, Kennes C, Verhoef G, Foschini MP, Stul M, et al. Histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity possibly related to lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s disease, paragranuloma subtype. Am J Surg Pathol 1992; 16: 37–48.

Greer JP, Macon WR, Lamar RE, Wolff SN, Stein RS, Flexner JM, et al. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas: diagnosis and response to therapy of 44 patients. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1742–1750.

Skinnider BF, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD . Bone marrow involvement in T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1997; 108: 570–578.

Chittal SM, Brousset P, Voigt JJ, Delsol G . Large B-cell lymphoma rich in T-cells and simulating Hodgkin’s disease. Histopathology 1991; 19: 211–220.

Osborne BM, Butler JJ, Pugh WC . The value of immunophenotyping on paraffin sections in the identification of T-cell rich B-cell large-cell lymphoma: lineage confirmed by JH rearrangement. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14: 933–938.

Arai E, Sakurai M, Nakayama H, Morinaga S, Katayama I . Primary cutaneous T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol 1993; 129: 196–200.

Krishnan J, Wallberg K, Frizzera G . T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a study of 30 cases, supporting its histologic heterogeneity and lack of clinical distinctiveness. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18: 455–465.

Dommann SNW, Dommann-Scherrer CC, Zimmerman D, Dours-Zimmermann M-T, Hassam S, Burg G . Primary cutaneous T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a case report with a 13-year follow-up. Am J Dermatopathol 1995: 17: 618–624.

Take H, Kubota K, Fukuda T, Shinonome S, Ishikawa O, Shirakura T . An indolent type of Epstein-Barr virus-associated T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma of the skin: report of a case. Am J Hematol 1996; 52: 221–223.

Sander CA, Kaudewitz P, Kutzner H, Simon M, Schirren CG, Sioutos N, et al. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma presenting in skin. A clinicopathologic analysis of six cases. J Cutan Pathol 1996; 23: 101–108.

Wollina U . Complete response of a primary cutaneous T-cell-rich B cell lymphoma treated with interferon α2a. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1998; 124: 127–129.

Dunphy CH, Nahass GT . Primary cutaneous T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas with flow cytometric immunophenotypic findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1999; 123: 1236–1240.

Beljaards RC, Kaudewitz P, Berti E, Gianotti R, Neumann C, Rosso R, et al. Primary cutaneous CD-30+ large cell lymphoma: definition of a new type of cutaneous lymphoma with a favorable prognosis. A European multicenter study of 47 patients. Cancer 1993; 71: 2097–2104.

Vergier B, Beylot-Barry M, Pulford K, Michel P, Bosq J, de Muret A, et al. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic and prognostic features of CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1192–1202.

Yang B, Tubbs RR, Finn W, Carlson A, Pettay J, His ED . Clinicopathologic reassessment of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with immunophenotypic and molecular genetic characterization. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 694–702.

Macon WR, Cousar JB, Waldron JA Jr, Hsu SM . Interleukin-4 may contribute to the abundant T-cell reaction and paucity of neoplastic B cells in T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas. Am J Pathol 1992; 141: 1031–1036.

Loke SL, Ho F, Srivastava G, Fu KH, Leung B, Liang R . Clonal Epstein-Barr virus genome in T-cell-rich lymphomas of B or probable B lineage. Am J Pathol 1992; 140: 981–989.

Baddoura FK, Chan WC, Masih AS, Mitchell D, Sun NC, Weisenburger DD . T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1995; 103: 65–75.

Brauninger A, Kuppers R, Spieker T, Siebert R, Strickler JG, Schlegelberger B, et al. Molecular analysis of single B cells from T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma shows the derivation of the tumor cells from mutating germinal center B cells and exemplifies means by which immunoglobulin genes are modified in germinal center B cells. Blood 1999; 93: 2679–2687.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Griffin, C., Mann, R. et al. Primary Cutaneous T-Cell–Rich B-Cell Lymphoma: Clinically Distinct from Its Nodal Counterpart?. Mod Pathol 14, 10–13 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880250

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880250