Abstract

Twenty-two cases of oncocytic thymic neuroendocrine carcinomas (carcinoid tumors) are presented. The patients were 17 men and 5 women between the ages of 26 and 84 years (median, 55 years). Nine were asymptomatic, and the tumor was found on routine examination; four patients presented with chest pain, two with weight loss, two with multiple endocrine neoplasia I syndrome, and one with Cushing’s syndrome. Surgical resection of the mediastinal tumor was performed in all cases. The lesions were described as soft, light tan to brown, measuring from 3 to 20 cm in greatest diameter. On cut section, the tumors showed a homogeneous surface, soft consistency, and focal areas of hemorrhage. Microscopically, the lesions were characterized by nests or trabeculae of tumor cells that contained abundant granular to densely eosinophilic cytoplasm, with round to oval nuclei and in some areas prominent nucleoli. Mitotic figures ranged from 2 to 10 per 10 high-power fields; foci of comedonecrosis were seen in all cases. Immunohistochemical studies including broad spectrum keratin, CAM 5.2, chromogranin, synaptophysin, Leu-7, and p53 were performed in 12 cases. All of the tumors were strongly positive for CAM 5.2 low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, 11 showed strong positive reaction for Leu-7, 10 for broad-spectrum keratin, 8 for chromogranin, 7 for synaptophysin, and only 1 case showed focal positive staining of the tumor cells for p53. Clinical follow-up of 14 patients showed that 10 were alive between 2 and 11 years, and 4 patients had died of tumor from 4 to 11 years after diagnosis. Patients with good clinical outcome were those whose tumors showed low mitotic activity and minimal nuclear pleomorphism, whereas those who had died of their tumors were those whose tumors were characterized by marked nuclear atypia and higher mitotic rates. Oncocytic thymic carcinoids should be added to the differential diagnosis of anterior mediastinal neoplasms characterized by a monotonous population of tumor cells with prominent oncocytic features.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the thymus are unusual neoplasms that may take the form of either moderately and well-differentiated tumors (thymic carcinoid) or poorly differentiated neoplasms (small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the thymus). Thymic neuroendocrine carcinomas may display a diverse spectrum of differentiation. Tumors composed predominantly of spindle cells (1, 2), with mucinous stroma (3), with divergent cell lines including mesenchymal elements and amyloid-like stroma (4, 5, 6), and cases showing transitional areas with small cell carcinoma (7) have been described in the literature.

We present a study of 22 cases of another unusual morphologic variant of primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the thymus characterized by prominent oncocytic features. The clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and differential diagnostic features of these lesions are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty-two cases of primary thymic neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus (thymic carcinoid) with prominent oncocytic features were identified from 146 cases of thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms found in the files of the Department of Pulmonary & Mediastinal Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Mount Sinai Medical Center of Greater Miami, Florida, over a 35-year period (1960 to 1995).

From 1 to 12 (average, 5) hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections were available for review in all cases. Histochemical stains for periodic acid-Schiff with and without diastase and mucicarmine were available in selected cases. For immunohistochemical studies, representative formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were available in 12 cases and were incubated with antibodies against CAM 5.2 low-molecular-weight keratin (Becton-Dickinson, Mount View, CA), broad-spectrum keratin cocktail (Dako, Carpinteria, CA; 1:3000), chromogranin (Enzo, New York, NY), synaptophysin (Dako; 1:20), Leu-7 (Dako), and p53 (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA; 1:10) by the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex technique. Sections stained with antibodies for CAM 5.2, chromogranin, and p53 were treated using a microwave epitope retrieval technique with 10 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0, at 700 watts for 20 min. Nonimmune rabbit and mouse serum was substituted for negative controls. Appropriate positive controls were run concurrently for every antibody tested.

For clinical follow-up, a questionnaire was developed and mailed to the respective contributing physicians or tumor registries over a period of 24 months. Information requested included gender, age, presenting symptoms and signs, significant history (namely, the existence of a similar tumor within the lung or extrathoracic area), gross findings, treatment, and follow-up. Responses to the questionnaire were obtained in 14 cases.

RESULTS

Clinical Features

The patients were 17 men and 5 women (M:F ratio, 3:1) between the ages of 26 to 84 years (median: 55 years). Nine patients were asymptomatic, and the tumors were discovered on routine medical examination. Four patients presented with symptoms of chest pain, two with weight loss, and three with endocrine abnormalities, including multiple endocrine neoplasia I syndrome (MEN-I) in two and Cushing’s syndrome in one. In four patients, no information regarding presenting or associated symptoms could be obtained. All of the tumors were localized to the anterior mediastinum at the time of diagnosis and were treated by surgical excision. None of the patients had any history or clinical evidence of tumor elsewhere.

Gross Features

The tumors were described as fairly well-circumscribed soft masses measuring from 3 to 20 cm in greatest diameter. On cut section, the tumors showed a homogeneous, light tan to brown surface with focal areas of hemorrhage.

Histopathologic Features

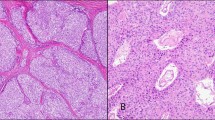

On scanning magnification, the tumors were composed of a monotonous cellular proliferation showing a vaguely “organoid” appearance, with the formation of discrete nests of tumor cells separated by thin fibroconnective tissue septa or forming cords and ribbons that imparted the lesions with a trabecular growth pattern (Fig. 1). Occasionally, the cells were arranged in a haphazard fashion without any particular pattern and were embedded in a loose fibromyxoid stroma. On higher magnification, the tumor cell population was composed of large- to medium-sized, round to polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with a granular appearance, round to oval nuclei, and occasionally prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2). In areas, the oncocytic tumor cells were seen to merge with foci showing more conventional, nononcocytic cytologic features of carcinoid tumors. Mitotic figures were present in all cases and varied from 2 to fewer than 10 per 10 high-power fields (HPF). The tumors were divided into well-differentiated tumors (low grade) and moderately differentiated tumors (intermediate grade) on the basis of their cytologic features and mitotic rate. Fourteen cases showed features of well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma and were characterized by relatively bland round to oval nuclei with occasionally prominent nucleoli, focal areas of comedonecrosis, and low mitotic activity (average, 2 to 3 mitotic figures/10 HPF) (Fig. 3). Eight cases showed features of moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma and were characterized by more pronounced nuclear pleomorphism, with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei, occasional bizarre nuclear shapes, nucleolar prominence, and higher mitotic rates (4 to 10 mitotic figures/10 HPF) (Fig. 4). Small foci of comedonecrosis were seen in all cases; however, the areas of necrosis were more numerous and extensive in the moderately differentiated tumors. Foci of dystrophic calcifications were present in 12 cases; the dystrophic calcifications generally were associated with areas of necrosis. In three cases, focal areas composed predominantly of spindle cells with elongated nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and inconspicuous nucleoli were also present. Periodic acid-Schiff and mucicarmine stains were negative in the tumor cells in all cases.

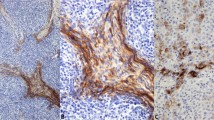

Immunohistochemical Features

Twelve cases were studied using antibodies for CAM 5.2, keratin cocktail, chromogranin, synaptophysin, Leu-7, and p53. Ten cases showed positive staining in the tumor cells for keratin, 11 showed positive staining for Leu-7, 8 for chromogranin, and 7 for synaptophysin. All cases showed positive staining for CAM 5.2 antibodies. It is interesting that only one case showed focal positive staining for p53 antibody.

Follow-Up

Clinical follow-up information was obtained in 14 patients over a period of 2 to 11 years (median, 6 years). Ten patients were alive and well from 2 to 11 years after diagnosis, whereas 4 patients had died of tumor over a period of 4 to 11 years. No follow-up information could be obtained for eight patients. Three of the four patients who had died had moderately differentiated tumors with high mitotic rates and marked cytologic atypia, whereas 11 of the 14 patients who were alive and well had well-differentiated tumors with low mitotic rates and mild nuclear atypical features. The three patients with associated MEN-I or Cushing’s syndrome were alive at the time of follow-up; the tumors in these patients corresponded to well-differentiated (low-grade) neuroendocrine carcinomas.

DISCUSSION

Primary thymic neuroendocrine carcinomas (thymic carcinoids) are unusual neoplasms that account for 2 to 4% of all mediastinal tumors (8, 9). Rosai and Higa (10) are credited with the first description of such tumors in the thymic region. These authors also were the first to point out that thymic tumors previously reported in association with Cushing’s syndrome most likely represented neuroendocrine tumors (11, 12, 13). Numerous reports of similar lesions in the thymus have been presented in the form of case reports or small series of cases (2, 5, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53).

The term carcinoid tumor was introduced in the early 1900s by Obendorfer (54) for a group of tumors of the small intestine that behaved better than conventional carcinomas. Since then, this term has been widely applied to a variety of well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms at various sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, lung, and thymus (9, 55, 56). Duh et al. (8) stated that thymic carcinoids are clinically malignant in approximately 82% of cases, whereas bronchial carcinoids are malignant in only 26% of cases. Also, Dusmet and McKneally (57) stated that although bronchial carcinoids may not influence life expectancy, thymic carcinoids, regardless of their histopathologic features, have a poor prognosis. Therefore, it may be argued that thymic carcinoids should be coded as “atypical” following the designation given by Arrigoni et al. (58, 59) to similar tumors in the lung. Conversely, there are those who consider the term carcinoid anachronistic and would rather classify such tumors within the spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas (60). We fully support the latter philosophy and believe that thymic carcinoids should be regarded as belonging within the spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas and that they should be further categorized on the basis of their cytologic features into well-, moderately, and poorly differentiated tumors.

Primary thymic neuroendocrine carcinomas may display a broad spectrum of differentiation and morphologic appearances, ranging from well-differentiated lesions with the classical features of carcinoid tumors elsewhere to poorly differentiated neoplasms indistinguishable from small cell carcinomas of the lung. The well-differentiated tumors, in particular, have shown a tendency to adopt unusual cytologic appearances and growth patterns that may introduce difficulties for diagnosis, including prominent spindling of the tumor cells, a small cell pattern reminiscent of lymphoma, and tumors with a variety of stromal changes that may raise the possibility of alternative conditions in the differential diagnosis (61). In the present study, we describe another unusual morphologic variant of primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the thymus that may also cause difficulties for diagnosis because of its prominent oncocytic features. It is interesting that primary thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms that show such features have been only rarely reported (62). This may be because these tumors are underrecognized rather than actually rare. In the present study, the tumors were identified from among 146 cases of primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the thymus, accounting for approximately 15% of the total of primary thymic neuroendocrine carcinomas (carcinoids) reviewed from our files over a 35-year period.

In our study, we were able to demonstrate that oncocytic carcinoid tumors are also associated with endocrinopathies and that they may also show different degrees of cellular atypia or differentiation. For instance, in 14 of our cases, the cellular atypia was mild and the mitotic count was in the range of 2 to 3 mitotic figures/10 HPF. Although foci of comedonecrosis were evident in all cases, they were usually focal rather than extensive in the well-differentiated tumors. Therefore, we classified these tumors as well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas with oncocytic features. However, eight cases showed more pronounced cellular atypia with irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and an increase in mitotic activity in the range of 4 to 10 mitoses/10 HPF. Moderately differentiated tumors correspond to moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas with oncocytic features. The majority of oncocytic neuroendocrine tumors in our study belonged to the better differentiated end of the spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinoma; oncocytic features in thymic carcinoids may therefore be associated with a better prognosis. We also noted that the association of Cushing’s syndrome or MEN-I did not alter the behavior of these tumors.

The differential diagnosis of oncocytic neuroendocrine carcinomas of the thymus includes metastatic carcinomas, particularly from breast and kidney, metastatic malignant melanoma, malignant mesothelioma, paraganglioma, and parathyroid adenomas (63, 64). The last two tumors, in particular, also show evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation using neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin and synaptophysin and may also display prominent oncocytic features. Mediastinal paragangliomas can also closely resemble oncocytic carcinoids histologically by virtue of their prominent nesting pattern (Zellballen). However, paragangliomas are usually negative for epithelial markers such as keratin or CAM 5.2 low-molecular-weight keratin (63). In addition, paragangliomas may show marked cellular pleomorphism with nucleomegaly, but mitotic activity and areas of necrosis are rarely seen. Parathyroid adenomas can also show granular or densely eosinophilic cytoplasm and display a prominent organoid architecture; however, these tumors will be strongly periodic acid-Schiff positive, whereas carcinoids will show negative reaction using periodic acid-Schiff histochemical stain. In addition, immunohistochemical stains for parathyroid hormone will be of value in equivocal cases, such as in small thoracoscopic biopsies in which the distinction may not be so easy on the basis of routine microscopy. Other conditions that may enter in the differential diagnosis include metastatic carcinomas with prominent oncocytic changes, such as breast cancer or renal cell carcinoma, malignant mesothelioma involving the mediastinal pleura, and metastatic malignant melanoma. These can easily be distinguished from oncocytic carcinoids by a combination of immunohistochemical stains and a careful clinical history. In general, the majority of such conditions will show negative results with neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin and synaptophysin.

We have presented 22 cases of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the thymus with prominent oncocytic features. The majority of cases in our study corresponded to low-grade, well-differentiated tumors (low mitotic activity, mild cellular atypia) that followed a favorable clinical course after surgical excision. Attention to cytologic features of atypia and mitotic activity are of importance, however, to identify cases that may follow a more aggressive biologic behavior.

References

Levine GD, Rosai J . A spindle cell variant of thymic carcinoid tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1976; 100: 293–300.

Manes JL, Taylor HB . Thymic carcinoid in familial multiple endocrine adenomatosis. Arch Pathol 1973; 95: 252–255.

Suster S, Moran CA . Thymic carcinoid with prominent mucinous stroma: report of a distinctive morphologic variant of thymic neuroendocrine neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 1277–1285.

Kuo TT . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus with divergent sarcomatoid differentiation: report of a case with histogenetic consideration. Hum Pathol 1994; 25: 319–323.

Paties C, Zangrandi A, Vasallo G, Rindi G, Solcia E . Multidirectional carcinoma of the thymus with neuroendocrine and sarcomatoid components and carcinoid syndrome. Pathol Res Pract 1991; 187: 170–177.

Sensaki K, Aida S, Takagi K, Shibata H, Ogata T, Tanaka S, et al. Coexisting undifferentiated thymic carcinoma and thymic carcinoid tumor. Respiration 1993; 60: 247–249.

Wick MR, Scheithauer BW . Oat-cell carcinoma of the thymus. Cancer 1982; 49: 1652–1657.

Duh QY, Harbarger CP, Geist R, Gamsu G, Goodman PC, Gooding GAW, et al. Carcinoids associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Am J Surg 1987; 154: 142–148.

Viebahn R, Hiddemann W, Klinke F, Bassewitz DB . Thymus carcinoid. Pathol Res Pract 1985; 180: 445–448.

Rosai J, Higa E . Mediastinal endocrine neoplasm of probable thymic origin related to carcinoid tumor. Cancer 1972; 29: 1061–1074.

Duguid JB, Kennedy AM . Oat-cell tumours of mediastinal glands. J Pathol 1932; 23: 93–99.

Kay S, Willson MA . Ultrastructural studies of an ACTH-secreting thymic tumor. Cancer 1970; 26: 445–452.

Rosai J, Higa E, Davie J . Mediastinal endocrine neoplasm in patients with multiple endocrine adenomatosis: a previously unrecognized association. Cancer 1972; 29: 1075–1083.

Asbun HJ, Calabria RP, Calmes S, Lang AG, Bloch JH . Thymic carcinoid. Am Surg 1991; 57: 442–445.

Birnberg FA, Webb WR, Selch MT, Gamsu G, Goodman PC . Thymic carcinoid tumors with hyperparathyroidism. Am J Radiol 1982; 139: 1001–1004.

Blom P, Johannessen JV . Mediastinal mass in a young man. Ultrastruct Pathol 1983; 4: 391–395.

Brown LR, Aughenbaugh GL, Wick MR, Baker BA, Salassa RM . Roentgenologic diagnosis of primary corticotropin-producing carcinoid tumors of the mediastinum. Radiology 1982; 142: 143–148.

Chalk S, Donald KJ . Carcinoid tumour of the thymus. Virchows Arch [A] 1977; 377: 91–96.

DeLellis RA, Wolfe HJ . Calcitonin in spindle cell thymic carcinoid tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1976; 100: 340.

Economopoulos GC, Lewis JW, Lee MW, Silverman NA . Carcinoid tumors of the thymus. Ann Thorac Surg 1990; 50: 58–61.

Fetissof F, Boivin F . Microfilamentous carcinoid of the thymus: correlation of ultrastructural study with Grimelius stain. Ultrastruct Pathol 1982; 3: 9–15.

Fishman ML, Rosenthal S . Optic nerve metastasis from a mediastinal carcinoid tumour. Br J Ophthalmol 1976; 60: 583–588.

Floros D, Dosios T, Tsourdis A, Yiatromanolakis N . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus with multiple endocrine adenomatosis. Pathol Res Pract 1982; 175: 404–409.

Gartner LA, Voorhess ML . Adrenocorticotropin hormone-producing thymic carcinoid in a teenager. Cancer 1993; 71: 106–111.

Gelfand ET, Basualdo CA, Callaghan JC . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus associated with recurrent pericarditis. Chest 1981; 79: 350–351.

Herbst WM, Kummer W, Holmann W, Otto H, Heym C . Carcinoid tumors of the thymus: an immunohistochemical study. Cancer 1987; 60: 2465–2470.

Hughes UP, Ancalmo N, Leonard GL, Ochsner JL . Carcinoid tumors of the thymus gland: report of a case. Thorax 1975; 30: 470–475.

Huntrakoon M, Lin F, Heitz PU, Tomita T . Thymic carcinoid tumor with Cushing’s syndrome: report of a case with electron microscopic and immunoperoxidase studies for neuron-specific enolase and corticotropin. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984; 108: 551–554.

Kimura N, Ishikawa T, Sasaki Y, Sasano N, Onodera K, Shimizu Y, et al. Expression of prohormone convertase, PC2, in adrenocorticotropin-producing thymic carcinoid with elevated plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81: 390–395.

Kogan J . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus. Postgrad Med 1984; 75: 291–296.

Lieske TR, Kincaid J, Sunderrajan JV . Thymic carcinoid with cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Arch Intern Med 1985; 145: 361–363.

Lokich JJ, Li F . Carcinoid of the thymus with hereditary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Intern Med 1978; 89: 364–365.

Loon G, Schiby G, Milo S . Lesions of the thymus. A study of 53 cases. Isr J Med Sci 1980; 16: 433–439.

Lowenthal RM, Gumpel JM, Kreel L, McLaughlin JE, Skeggs BL . Carcinoid tumour of the thymus with systemic manifestations: a radiological and pathological study. Thorax 1974; 92: 553–558.

Marchevsky AM, Dikman SH . Mediastinal carcinoid with an incomplete Sipple’s syndrome. Cancer 1979; 43: 2497–2501.

Miettinen M, Partanene S, Lehto VP, Virtanene I . Mediastinal tumors: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical evaluation of intermediate filaments as diagnostic aids. Ultrastruct Pathol 1983; 4: 337–347.

Miura K, Sasaki C, Katsushima I, Ohtomo T, Sato S, Demura H, et al. Pituitary adrenocortical studies in a patient with Cushing’s syndrome induced by thymoma. J Clin Endocrinol 1967; 27: 631–637.

Mizuno T, Masaoka A, Hashimoto T, Shibata K, Yamakawa Y, Torii K, et al. Coexisting thymic carcinoid tumor and thymoma. Ann Thorac Surg 1990; 50: 650–652.

Pimstone BL, Uys CJ, Vogelpoel L . Studies in a case of Cushing’s syndrome due to an ACTH-producing thymic tumour. Am J Med 1972; 53: 521–528.

Rao U, Takita H . Carcinoid tumour of possible thymic origin: a case report. Thorax 1977; 32: 771–776.

Salyer WR, Salyer DC, Egglestone JC . Carcinoid tumors of the thymus. Cancer 1976; 37: 958–973.

Steen RE, Rapelrud H, Haug E, Frey H . In vivo and in vitro inhibition by ketoconazole of ACTH secretion from a human thymic carcinoid tumour. Acta Endocrinol 1991; 125: 331–334.

Stewart CA, Kingston CW . Carcinoid tumour of the thymus with Cushing’s syndrome. Pathology 1980; 12: 487–494.

Sundstrom C, Wilander E . Thymic carcinoid: a case report. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1976; 84: 311–316.

Tanaka T, Tanaka S, Kimura H, Ito J . Mediastinal tumor of thymic origin and related to carcinoid tumor. Acta Pathol Jpn 1974; 24: 413–426.

Vener JD, Zuckerbraun L, Goodman D . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus associated with a parathyroid adenoma. Arch Otolaryngol 1982; 108: 324–326.

Wang DY, Chang DB, Kuo Sh, Yang PC, Lee YC, Hsu HC, et al. Carcinoid tumours of the thymus. Thorax 1994; 49: 357–360.

Waxman DM, Millac P . Spinal cord compression due to metastatic spread from a primary carcinoid tumour of the thymus. Clin Oncol 1993; 5: 321–322.

Wick MR, Scheithauer BW . Thymic carcinoid. Cancer 1984; 53: 475–484.

Wick MR, Scott RE, Li YC, Carney JA . Carcinoid tumor of the thymus: a clinicopathologic report of seven cases with a review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc 1980; 55: 246–254.

Wollensak G, Herbst EW, Beck A, Schaefer HE . Primary thymic carcinoid with Cushing’s syndrome. Virchows Arch [A] Pathol Anat 1992; 420: 191–195.

Zahner J, Borchard F, Schmitz U, Scheneider W . Thymus carcinoid in multiple endocrine neoplasms type I. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1994; 119: 135–140.

Zeiger MA, Swartz SE, MacGillivray DC, Linnoila I, Shakir M . Thymic carcinoid in association with MEN syndromes. Am Surg 1992; 58: 430–434.

Obendorfer S . Oncocytic neuroendocrine carcinomas of the mediastinum. Frankfurt Z Pathol 1907; 1: 426–430.

Smith RA . Bronchial carcinoid tumours. Thorax 1969; 24: 43–47.

Williams ED, Sandler M . The classification of carcinoid tumours. Lancet 1963; 2: 238–239.

Dusmet ME, McKneally MF . Pulmonary and thymic carcinoid tumors. World J Surg 1996; 20: 189–195.

Arrigoni MG, Woolner LB, Bernatz PE . Atypical carcinoid tumors of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1972; 64: 413–421.

Valli M, Fabris GA, Dewar A, Chikte S, Fisher C, Corrin B, et al. Atypical carcinoid tumours of the thymus: a study of eight cases. Histopathology 1994; 24: 371–375.

Montpreville VT, Macchicarini P, Dulmet E . Thymic neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid): a clinicopathologic study of fourteen cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111: 134–141.

Suster S . Mediastinal pathology. In: Weidner N, editor. The difficult diagnosis in surgical pathology. Philadelphia:W.B. Saunders; 1995. p. 143–176.

Yamaji I, Iimura O, Mito T, Yoshida S, Shimamoto K, Minase T . An ectopic ACTH-producing oncocytic carcinoid tumor of the thymus: report of a case. Jpn J Med 1984; 23: 62–66.

Moran CA, Suster S, Fishback N, Koss MN . Mediastinal paragangliomas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 16 cases. Cancer 1993; 72: 2358–2364.

Wick MR, Rosai J . Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the mediastinum. Semin Diagn Pathol 1991; 8: 35–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The opinions expressed herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as the official view of the Department of the Army or Defense.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moran, C., Suster, S. Primary Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (Thymic Carcinoid) of the Thymus with Prominent Oncocytic Features: A Clinicopathologic Study of 22 Cases. Mod Pathol 13, 489–494 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880085

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880085

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A rare case of thymic carcinoid presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms and pericardium effusion

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2021)

-

Thymus neuroendocrine tumors with CTNNB1 gene mutations, disarrayed ß-catenin expression, and dual intra-tumor Ki-67 labeling index compartmentalization challenge the concept of secondary high-grade neuroendocrine tumor: a paradigm shift

Virchows Archiv (2017)

-

Images in Endocrine Pathology

Endocrine Pathology (2013)

-

Oncocytic mania: A review of oncocytic lesions throughout the body

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2011)