Abstract

We report seven cases of renal medullary carcinoma collected from several institutions in Brazil. In spite of a relatively high incidence of sickle cell trait in Brazil, this is a rare tumor. All patients were males between the ages of 8 and 69 years (mean 22 years). From the collected information, the most frequent presenting symptoms were gross hematuria and flank or abdominal pain. The duration of symptoms ranged from 1 week to 5 months. Most of the tumors were poorly circumscribed arising centrally in the renal medulla. Size ranged from 4 to 12 cm (mean 7 cm) and hemorrhage and necrosis were common findings. All seven cases described showed sickled red blood cells in the tissue and six patients were confirmed to have sickle cell trait. All cases disclosed the characteristic reticular pattern consisting of tumor cell aggregates forming spaces of varied size, reminiscent of yolk sac testicular tumors of reticular type. Other findings included microcystic, tubular, trabecular, solid and adenoid-cystic patterns, rhabdoid-like cells and stromal desmoplasia. A peculiar feature was suppurative necrosis typically resembling microabscesses within epithelial aggregates. The medullary carcinoma of the 69-year-old patient was associated with a conventional clear cell carcinoma. To our knowledge, this association has not been previously reported and the patient is the oldest in the literature. The survival after diagnosis or admission ranged from 4 days to 9 months. The 8-year-old African–Brazilian patient with a circumscribed mass is alive and free of recurrence 8 years after diagnosis. This case raises the question whether a periodic search for renal medullary carcinoma in young patients who have known abnormalities of the hemoglobin gene and hematuria could result in an early diagnosis and a better survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In 1995, Davis et al,1 reported 34 cases of a very aggressive neoplasm with peculiar microscopic morphology highly predictive of finding sickled erythrocytes in the tissue. The authors designated this tumor ‘renal medullary carcinoma’ and considered it the seventh sickle cell nephropathy.

Renal medullary carcinoma is a rare tumor that arises centrally, in the renal medulla, grows rapidly in an infiltrative pattern and invades the renal sinuses, with nearly all patients dying of the disease within several months after diagnosis. This tumor typically affects young patients and is almost exclusively associated with sickle cell trait. The origin and pathogenesis of renal medullary carcinoma are not completely understood.

Seven cases of renal medullary carcinoma are reported including one case of favorable evolution. All cases were examined for clinical and morphological features and six of them were also studied for immunohistochemical profile. To our knowledge, this is the first Brazilian multiinstitutional report on renal medullary carcinoma. Case 1 has been reported previously.2

Materials and methods

Seven cases of renal medullary carcinoma were collected with the collaboration of several Brazilian pathologists that searched for cases of renal medullary carcinoma in their institution's files. Sections of each case were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin blocks were available for all cases, except for the seventh case with two renal tumors. The antibodies used, their sources and their dilutions are listed in Table 1. These antibodies were selected because of their utility in the differentiation of several renal tumors, including collecting duct carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma. The immunostains were prepared following the biotin-avidin-peroxidase method and the reaction product was visualized with diaminobenzidine.3

Clinical Findings

The clinical data are summarized in Table 2. The age of the patients ranged from 8 to 69 years and all were males. Of five patients with race information available, four were African-Brazilians and one was white. Sickle cell status was known for six patients, five had sickle cell trait and one a positive sickling test.

The clinical presentation was available for six patients, all of them presented with hematuria. Other symptoms included flank or back pain (three cases), weight loss (two cases), neurologic deficit (one case) and dyspnea (one case). The duration of presenting symptoms was known for five cases and ranged from 3 weeks to 5 months.

The right kidney was involved in five cases (Figure 1) and the left in two cases. The patient with bilateral tumors revealed a larger mass in the right kidney and the left renal mass was considered a contralateral metastasis.

The youngest and the oldest patients had tumors restricted to the kidney, whereas the other five patients had metastatic disease at presentation. The sites of metastases were lungs (n=5), lymph nodes (n=3), bones (n=2), contralateral kidney (n=1), liver (n=1) and adrenal (n=1). One case had massive retroperitoneal disease with vertebral infiltration and spinal cord compression.

Radical nephrectomy was performed in four cases. One patient was considered inoperable and one patient died before any treatment was given and an autopsy was performed. Three patients were submitted to chemotherapy and two of them also received radiotherapy. The response to either one treatment was poor for all three cases.

Follow-up data were available for six patients, five died of the disease and their survival after diagnosis/admission ranged from 4 days to 9 months. The youngest patient is alive and free of recurrence 8 years after the diagnosis.

Pathological Findings

Gross characteristics

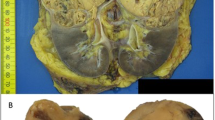

The right kidney was affected in all except two cases (Figure 2). Gross descriptions were available for five tumors. Most of the tumors were poorly circumscribed. The tumor mass was firm to rubbery with whitish to gray color and all of them occupied a predominant central location. The size ranged from 3.5 to 7.8 cm and all of them had areas of necrosis, except for the sixth case (smaller tumor), which showed only hemorrhagic areas.

The surgical specimen of the seventh case revealed two distinct tumors. The smaller tumor was located in the renal medulla and had the same characteristics described above. The larger mass was situated predominantly at the renal cortex and measured 8.1 cm in the highest diameter. This tumor was yellowish with hemorrhagic areas and the morphological examination revealed a conventional renal cell carcinoma.

Microscopic characteristics

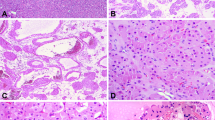

All seven tumors had very similar microscopic characteristics. A reticular pattern of growth and a prominent stromal desmoplasia were the most constant features. The reticular pattern consisted of tumor cell aggregates forming spaces of varied size, reminiscent of yolk sac testicular tumors of reticular type (Figure 3). The stromal desmoplasia (Figure 4) showed several appearances among the tumors and within the same tumor: densely collagenous, edematous, mucoid or myxoid. Microcystic (Figure 5), tubular, trabecular, solid (Figure 6) and adenoid-cystic (Figure 7) patterns were also identified in some of the tumors.

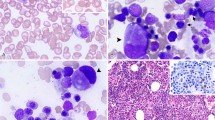

Cytologically, tumor cells showed dark eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with conspicuous and usually prominent nucleoli (Figure 6). The presence of rhabdoid-like cells was observed in four cases. The tumors diffusely infiltrated the renal parenchyma (except for the sixth case) as observed in urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis, but other histological aspects were distinct from this neoplasm. All cases showed at least focal acute inflammatory infiltrate and two cases had areas of suppurative necrosis typically resembling microabscesses within epithelial aggregates (Figure 8). Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate was prominent in four cases and focal in the remaining ones. Sickled red blood cells were seen in blood vessels in all of the seven tumors (Figure 9), including the case with no data on the hemoglobin status of the patient.

The sixth case of an 8-year-old boy was partially circumscribed and although the architectural and cytological aspects were very similar to the other tumors (Figure 10), this tumor did not show the diffuse infiltration of the renal parenchyma that is characteristic of the renal medullary carcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry

All tumors showed homogeneous expression of cytokeratin pool (AE1/AE3), low molecular weight cytokeratin (35βH11) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Coexpression of vimentin was found in all but one tumor. High molecular weight cytokeratin was focally positive in one case and diffusely positive in the sixth case of unusual presentation and evolution. Cytokeratin 7 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were focally positive in all cases and cytokeratin 20 negative in all but one case in which there was a weak focal positivity.

Discussion

Renal medullary carcinoma is a rare, rapidly growing tumor that affects young individuals with sickle cell trait. This tumor was described in 1995 by Davis et al,1 which considered it the seventh sickle cell nephropathy. The six sickle cell nephropathies previously described by Berman,4 in 1974, are gross hematuria, papillary necrosis, nephrotic syndrome, renal infarction, inability to concentrate the urine and pyelonephritis. All of them are to a certain extent related to the obstruction of blood vessels and tissue hypoxia resulting from red blood cell sickling. The renal medulla is particularly susceptible to damage in sickle cell disease due to its unique environment characterized by anoxia, hyperosmolarity and low pH that tend to promote hemoglobin S polymerization and red blood cell sickling.5

Over a period of 22 years, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology had collected only 34 cases,1 and over the next 5 years, only 15 more had been described.6 Simpson et al7 published a study in which a Medline search of the English literature for renal medullary carcinoma from 1995 through 2003 was conducted resulting in a total of 21 distinct reports identified, yielding 95 distinct cases, including the 3 new cases described by the authors. We have performed a Medline search via PubMed of the English literature using renal medullary carcinoma as a search term for the period from January 2003 to May 2007 and 16 distinct reports of new cases were found with a total of 35 cases, including the 3 cases published by Simpson7 in 2005 and the 7 cases presented here. The incidence of sickle cell trait in Brazil is 6.7% in African-Brazilians, 5.4% in Mulattos (persons with mixed White and African-Brazilian ancestry) and 0.21% in Whites.8 Considering the large population at risk, the tumor is, in fact, very rare suggesting that additional factors are likely necessary. This is the first report from Brazil as a result of the collaboration of several pathologists that searched for cases of renal medullary carcinoma in their institution's files.

Renal medullary carcinoma is typically seen in young patients with the sickle cell trait and exceptionally with sickle cell disease. All seven cases described here showed sickled red blood cells in the tissue and six patients were confirmed to have sickle cell trait. In one case (case 3), the hemoglobin profile was not studied. Renal medullary carcinoma shows a male predominance (2:1) and the mean age at presentation is approximately 22 years, with ages ranging from 5 to 40 years.1, 9, 10 Our cases confirmed the male predominance and the mean age was similar to the literature. As far as we know, the seventh case of the 69-year-old patient corresponds to the oldest patient with renal medullary carcinoma reported.

The most frequent presenting symptoms are gross hematuria and flank or abdominal pain. A palpable abdominal mass is often observed. Some patients may present with symptoms of metastatic disease. Spontaneous gross hematuria, the first sickle cell nephropathy, is usually unilateral and occurs at the same age range that of renal medullary carcinoma. It is worth noting, however, that most of these spontaneous benign bleedings occur from the left kidney and most of the renal medullary carcinomas arise on the right kidney.

Grossly, most of the tumors are poorly circumscribed arising centrally in the renal medulla. Size ranges from 4 to 12 cm (mean 7 cm) and hemorrhage and necrosis are common findings. The microscopic features previously described are characteristic of this tumor. The infiltrative pattern of growth contrasts with renal cell carcinoma and Wilms' tumor, which grow by expansion. Keratin AE1/AE3 is nearly always positive as is EMA, but typically less strong. CEA is usually positive. Some studies showed strong expression for low molecular cytokeratin (CAM 5.2), but no expression of high molecular cytokeratin.10, 11 Of 15 tumors analyzed by Swartz et al,10 cytokeratin 7 and 20 were heterogeneous and variable, and Ulex europeus was focally positive in a minority of cases. Electron microscopy may disclose intracytoplasmatic lumens with short microvilli, lipid vacuoles and intercellular junctions,10, 11 but no consistent ultrastructural characteristic specific of this neoplasm was identified.

The origin and pathogenesis of renal medullary carcinoma are not completely understood. Accumulated experience with radiographic and pathologic findings suggests that renal medullary carcinoma probably originates in the calyceal epithelium in or near the renal papillae,1 which could be the result of the chronic ischemic damage of the epithelium of the renal papillae related to sickled erythrocytes. Positivity for vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia induced factor supports that chronic hypoxia secondary to the hemoglobinopathy may be involved in the pathogenesis of renal medullary carcinoma.10

In several texts, renal medullary carcinoma is classified as a subtype of collecting duct carcinoma, in spite of their clinical, morphological and immunoprofile differences.10 In fact, the main differential diagnosis of renal medullary carcinoma is collecting duct carcinoma,12 for it shares certain features with renal medullary carcinoma. However, collecting duct carcinoma typically occurs in older patients without sickle cell trait, especially males with a mean age of 53 years.12 In addition, collecting duct carcinoma shows a predominantly tubulopapillary pattern, the inflammatory infiltrate is usually less prominent and dysplastic lesions are seen in the adjacent collecting ducts. Despite its central location in the kidney, the histological spectrum of collecting duct carcinoma is more closely related to renal cell carcinoma rather than to renal pelvic carcinoma.1 Besides, the characteristic immunoprofile of collecting duct carcinoma is positivity for high molecular weight cytokeratin (34βE12) and Ulex europeus agglutinin 1 lectin (UEA-1).12, 13, 14 Cytokeratin 34βE12 is frequently negative in renal medullary carcinoma and UEA-1 is present in only a minority of cases in a focal distribution.10

Renal medullary carcinoma shares similarities with high-grade urothelial carcinoma with regard to its location, infiltrating pattern and tumor cell morphology.15 Of interest is the case reported by Figenshau16 that showed an association of renal medullary carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma. The authors speculated whether the finding represents a collision tumor or dedifferentiation of the pelvic urothelial carcinoma. We report here a case of an association of renal medullary carcinoma and conventional renal cell carcinoma. To our knowledge, this association has not been previously reported in the literature and probably corresponds to an association by chance. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the tumors were distinct masses, situated in different areas of the renal parenchyma, the first was located centrally, in the renal medulla and the second in the renal cortex, suggesting that they represent a collision tumor.

The prognosis of renal medullary carcinoma is very poor due to the highly aggressive behavior of this neoplasm and to its resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Metastases are both lymphatic and hematogenous with liver and lungs most often involved. The mean duration of life after surgery is about 15 weeks9 and the longest documented survival for renal medullary carcinoma was 15 months.10 Chemotherapy has been known to prolong survival by few months, but generally, neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy has altered the course of the disease.17 We report one case of unusual outcome, in which the patient is alive and free of recurrence 8 years after surgery. This unique long survival is probably due to the early diagnosis of a small tumor restricted to the kidney and to the lack of prominent infiltrative growth. This case emphasizes the importance of considering renal medullary carcinoma in the differential diagnosis of young patients with sickle cell trait or disease presenting with hematuria and also raises question whether a screening for this neoplasm in such patients could result in an early diagnosis and a better survival.

References

Davis Jr CJ, Mostofi FK, Sesterhenn IA . Renal medullary carcinoma. The seventh sickle cell nephropathy. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1–11.

Leitao VA, Silva Jr W, Ferreira U, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma. Case report and review of the literature. Urol Int 2006;77:184–186.

Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H . Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques. A comparison between ABC labeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 1981;29:557–589.

Berman LB . Sickle cell nephropathy. JAMA 1974;228:1279.

Beutler E . Disorders of hemoglobin structure: sickle cell anemia and related abnormalities. In: Lichtman MA, Beutler E, Kipps TJ, Seligsohn U, Kaushansky K, Prchal JT (eds). Williams Hematology, 7th edn. McGraw-Hill: New-York, 2006, pp 667–700.

Khan A, Thomas N, Costello B, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma: sonographic, computed tomography, magnetic resonance and angiographic findings. Eur J Radiol 2000;35:1–7.

Simpson L, He X, Pins M, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma and ABL gene amplification. J Urol 2005;173:1883–1888.

Chapadeiro E, Maciel R, Jamra M, et al. Linfonodos, baço, medula óssea e sangue. Tumores do Sistema Hemolinfático. Timo. In: Lopes ER, Chapadeiro E, Raso P, Tafuri WL (eds). Bogliolo Patologia, 4th edn. Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, 1987, pp 651–652.

Davis Jr CJ . Renal medullary carcinoma. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, et al (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2004, pp 162–192.

Swartz MA, Karth J, Schneider DT, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma: clinical, pathologic, immunohistochemical, and genetic analysis with pathogenetic implications. Ped Urol 2002;60:1083–1089.

Rodriguez-Jurado R, Gonzalez-Crussi F . Renal medullary carcinoma. J Urol Pathol 1996;4:191–203.

Srigley JR, Eble JN . Collecting duct carcinoma of kidney. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:54–67.

Kennedy SM, Merino MJ, Linehan WM, et al. Collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney. Hum Pathol 1990;21:449–456.

Amin MB, Varma MD, Tickoo SK, et al. Collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney. Adv Anat Pathol 1997;4:85–94.

Yang XJ, Sugimura J, Tretiakova MS, et al. Gene expression profiling of renal medullary carcinoma: potential clinical relevance. Cancer 2004;100:976–985.

Figenshau RS, Basler JW, Ritter JH, et al. Renal medullary carcinoma. J Urol 1998;159:711–713.

Pisani P, Bray F, Parkin DM . Estimates of the world-wide prevalence of cancer for 25 sites in the adult population. Int J Cancer 2002;97:72–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, I., Billis, A., Guimarães, M. et al. Renal medullary carcinoma: report of seven cases from Brazil. Mod Pathol 20, 914–920 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800934

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800934

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Distinctive mechanisms underlie the loss of SMARCB1 protein expression in renal medullary carcinoma: morphologic and molecular analysis of 20 cases

Modern Pathology (2019)

-

Novel therapy for pediatric and adolescent kidney cancer

Cancer and Metastasis Reviews (2019)