Abstract

Atypical lentiginous melanocytic proliferations in elderly patients continue to pose a diagnostic dilemma with lesions variably categorized as dysplastic nevus, atypical junctional nevus, melanoma in situ (early or evolving) and premalignant melanosis. We present pigmented lesions from 16 patients (seven male and nine female) and with the exception of one case, all were older than 50 years of age. The anatomical sites included trunk (7), head and neck (6) and upper extremity (3). The clinical diagnosis was variable and included lentigo maligna, atypical nevus, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis and lentigo. The initial biopsies mimicked lentiginous nevus or dysplastic nevus and were characterized by a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction both as single cells and as small nests with areas of confluent growth, extending to the edges of the biopsy. The retiform epidermis was maintained and pagetoid spread of melanocytes was not prominent in hematoxylin- and eosin- stained sections. Dermal fibrosis was variably present and the melanocytic proliferation demonstrated cytological atypia. The subsequent re-excisions demonstrated similar atypical melanocytic proliferation occurring over a broad area flanking the prior biopsy sites. The diagnosis of melanoma was more easily recognized in the complete excision specimens. Immunohistochemical stains for Mitf and Mart-1 highlighted the extent of the basalar melanocytic proliferation as well as foci of pagetoid spread by melanocytes. Familiarity with this pattern of early melanoma should facilitate proper classification of lentiginous melanocytic proliferations in biopsies from older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The histopathological recognition of early cutaneous melanoma is to a large extent based on the presence of a proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction. This may occur in atrophic skin, such as that seen in lentigo maligna, or with prominent pagetoid spread as seen in superficial spreading melanoma. In acral sites, there may be a lentiginous proliferation of atypical melanocytes without much pagetoid spread, and with preservation of the epidermal architecture. Mixed patterns of intraepidermal melanocytic proliferation occur in some melanomas and there are melanomas that cannot be easily classified into the traditional groupings of lentigo maligna, superficial spreading or acral lentiginous types. We present a series of patients with early melanomas that on initial biopsy histologically demonstrated an atypical lentiginous melanocytic proliferation resembling a lentiginous or atypical (dysplastic) lentiginous nevus. The re-excision specimens showed an extensive junctional proliferation occurring over a broad area, maintaining a retiform pattern to the epidermis, demonstrating confluence of melanocytes along the basal layer of the epidermis, lacking concentric eosinophilic or lamellar fibroplasia, having focal pagetoid spread of melanocytes, and in two cases showing level II invasive melanoma.

Materials and methods

Three index cases in which the original biopsies were characterized by a prominent lentiginous proliferation of mildly atypical melanocytes, preservation of the epidermal rete ridge pattern, lack of prominent solar elastosis, little pagetoid spread and minimal dermal fibrosis, and in which the melanocytic proliferation extended to the edges of the biopsies, form the basis of this study. The biopsies in these initial three cases were originally interpreted as lentiginous nevi with no additional therapy provided at that time. The lesions persisted and progressed resulting in complete excision and in which the re-excised specimens demonstrated a similar broad proliferation. An additional 13 cases demonstrating similar findings were recovered from the files of Knoxville Dermatopathology Laboratory, over a period of 4 years. The patients' clinical and follow-up data were obtained and the hematoxylin- and eosin- (H and E) stained tissue sections were reviewed. All cases included both biopsy and re-excision specimens.

Immunohistochemistry

Monoclonal antibodies Melan-A / Mart-I (Dako, clone A103, Carpinteria, CA, USA; 1:200) and D5, recognizing human Mitf only (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA, Dr DE Fisher's laboratory, undiluted hybridoma culture supernatant) was used for immunostaining on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Compound nevi were used as positive controls, whereas removal of the primary antibody was used as negative controls. In the case of Mitf, only nuclear staining was regarded as positive.

Results

Clinical Data (Table 1)

There were seven men and nine women ranging in age from 43 to 90 years of age with a mean of 62.9 years. There were seven biopsies from the trunk (three lesions on the back and single lesions on the scapula, chest, breast and abdomen), six from the head–neck region (two lesions on the face, two lesions on the ear and two lesions on the neck) and three lesions were from the upper extremity. Our index cases (patients 3, 11 and 12) had their lesions re-excised 16 months, 3 years, and 3 years and 10 months, respectively. The reason for the delay in complete excision of these lesions was that in these three cases, the initial biopsies were interpreted as lentiginous junctional nevi. The lesions persisted and progressively enlarged, resulting in complete excision.

Biopsies

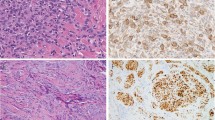

A similar melanocytic proliferation was noted in all biopsies. This was characterized by a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. The melanocytes were disposed as single cells and as small nests and were characterized by areas of confluent growth occurring over broad areas of the dermoepidermal junction (Figures 1a and b). The retiform epidermis was maintained. Focal pagetoid spread of melanocytes was evident in areas, but this was not a prominent finding in any of the biopsies. Slight dermal fibrosis was variably present, but was not well organized into either lamellar fibroplasia or concentric eosinophilic fibrosis. Cytologically, the melanocytes demonstrated atypia manifested by enlarged nuclei with thickened nuclear membranes and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1c). The nuclei approximated the size of adjacent keratinocyte nuclei. Marked cellular pleomorphism and anaplasia of melanocytes was not present. Many of the melanocytes had abundant gray cytoplasm with melanin pigment. The dominant cell type was epithelioid and only rare scattered spindled melanocytes were present. Extension of the melanocytic proliferation down follicles was noted. The melanocytic proliferation extended to the edges of the biopsies in all cases.

Biopsies from patients 1 and 4 demonstrating a similar lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. There is retention of the retiform epidermis with mild dermal fibrosis. The melanocytes are disposed in small nests and single cells (a and b). Higher magnification demonstrates epithelioid melanocytes with enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli (c).

Re-excisions

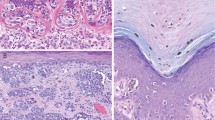

The melanocytic lesions were measured in the excision specimens and all were greater than 1 cm, with the broadest lesion measuring 2.5 cm in greatest dimension. All the lesions were macular with no pigmented nodules discernable. The re-excisions all showed a similar melanocytic proliferation flanking the initial biopsy site (Figure 2a). The melanocytic proliferation was broad in all cases and in two cases (patients 2 and 10), there was evidence of invasion into the papillary dermis, consistent with Clark anatomic level II invasion (Figure 2b). The Breslow thickness corresponded to 0.4 and 0.21 mm, respectively. Mitoses were not identified in either case and a dominant dermal nodule or ulceration was not present.

Re-excision specimen of patient 1 highlighting the extensive nature of the melanocytic proliferation. There is preservation of the retiform epidermis with virtual confluent proliferation of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction (a). Re-excised specimen from patient 2, demonstrating a focus of Clark level II invasion into the papillary dermis (b).

Immunohistochemistry

Mart-1 and Mitf staining in the biopsy and re-excision specimens highlighted the extent of the melanocytic proliferations (Figures 3–c). The broad nature of these lesions was made more apparent in the immunostained sections and pagetoid spread of individual melanocytes was also more readily identifiable with both immunostains. In the case of Mitf, the nuclear staining of individual melanocytes was helpful in semiquantifying the increase in the number of melanocytes.

The broad nature of the melanocytic proliferation is highlighted with melanocytic marker Mart-1 (a). Immunostaining with melanocytic markers Mart-1 (b) and Mitf (c) highlight the extent of the melanocytic proliferation and pagetoid spread of melanocytes, which are not readily identifiable on the H- and E-stained sections.

Discussion

Atypical lentiginous melanocytic proliferations in elderly patients continue to pose a diagnostic dilemma with lesions variably categorized as dysplastic nevus, atypical junctional nevus, melanoma in situ (early or evolving) and premalignant melanosis.1 The spectrum of lentiginous melanocytic lesions vary from benign, to atypical, to malignant (Table 2) and include benign lentiginous nevi, which are characterized by elongation of rete ridges with small nests of melanocytes located at the tips of rete. There is often an accompanying mild lymphohistocytic infiltrate with pigment incontinence and these lesions may evolve from a simple lentigo. Individual melanocytes do not demonstrate cytologic atypia. In contrast to lentiginous nevi, atypical (dysplastic) lentiginous nevus of the elderly demonstrates an irregular rete ridge system, with nests and single melanocytes irregularly distributed within the retiform epidermis. Focal confluent growth of melanocytes is present in the suprapapillary plates and focal atypia, characterized by larger irregular hyperchromatic nuclei, is present. Transition to melanoma in situ may be present, characterized by changes typically seen in lentigo maligna.2

Superficially, our cases shared histologic findings with lentiginous nevi (preservation of the retiform epidermis with nests of melanocytes at the tips of rete) and atypical lentiginous nevi (preservation of the retiform epidermis and lentiginous spread of atypical melanocytes). However, our cases were characterized by the confluent growth of atypical melanocytes spanning the entire lesion, similar to the proliferation seen in melanomas with a lentiginous junctional proliferation (lentigo maligna type, acral lentiginous type and mucosal lentiginous type).3, 4, 5, 6 In contrast to acral and mucosal lentiginous melanoma, our cases were all located on the head and neck, trunk and arm, and, histologically, there was preservation of the retiform epidermis and absence of prominent solar elastosis, in contrast to lentigo maligna. Immunohistochemical stains for Mitf and Mart-1 were useful in highlighting the extensive proliferation of basalar melanocytes as well as foci of pagetoid spread by melanocytes, not readily identifiable on the H- and E-stained sections. Taken together, our cases had features of atypical lentiginous nevi (retention of the retiform epidermal architecture) and lentigo maligna (confluent growth of atypical melanocytes). Based on the biological behavior and these overlapping histologic findings, we believe our lesions represent a variant of lentigo maligna, albeit with retention of the retiform epidermis.

Biologically, the lesions in our series appeared to persist and progress if left untreated. This course was made evident by our three index cases (patients 3, 11 and 12) whose initial biopsies were interpreted as atypical lentiginous junctional nevi for which no further therapy was implemented. The lesions persisted and progressively enlarged resulting in complete excisions 16 months, 3 years, and 3 years and 10 months, respectively. Recognition of this pattern of proliferation in the biopsy specimens prompted us to recommend re-excision in our subsequent 13 patients with similar findings in the re-excised specimens. Although only two of our 16 cases did have an invasive component corresponding to Clark level II indicating that these lesions have the ability to invade into the dermis, the time to acquire these properties may be prolonged and may explain their persistence as radial growth phase melanomas, similar to the natural biology of classical lentigo maligna.

In melanocytic lesions studied in older individuals, the most common was the dermal nevus,7, 8, 9 and with acquired nevi with a junctional component, there was a rapid drop-off in the presence of a junctional component with increasing age, with less than 10% of patients over the age of 60 years having a junctional component.10 Within this group of patients with a junctional component, there was a distinct category of lesions with overlapping histological features of a solar lentigo and an atypical melanocytic proliferation and the same database was used to analyze nevi in patients over 40 years of age.11 The lesions showed a continuous spectrum resembling senile lentigo with patchy junctional activity, to lesions with a superimposed atypical lentiginous, melanocytic proliferation, bordering on malignant melanoma in situ. The term pigmented lentiginous nevus with atypia was used for lesions bordering on in situ melanoma. Kossard et al2 described similar lesions, which they termed lentiginous dysplastic nevus of the elderly and lesions were commonly associated with transition to malignant melanoma in situ (typically as lentigo maligna).12 Weedon1 believes that this is an under-recognized clinicopathological entity and has been categorized in the past as dysplastic nevus, atypical junctional nevus, melanoma in situ (early or evolving) and premalignant melanosis.

The precise classification of atypical lentiginous melanocytic lesions remains a diagnostic dilemma. This study is an attempt to define a subset of lesions in elderly patients that we believe is melanoma with a lentiginous growth pattern, and most likely a variant of lentigo maligna. We base our findings on their biological behavior to persist and progress if left untreated, and histologically by the broadness of the lesions with the confluent growth of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, albeit with retention of the retiform epidermis. Progression to invasive melanoma in two of the cases was present.

In conclusion, we present 16 elderly patients with radial growth phase melanoma demonstrating a histological pattern resembling superficially a lentiginous or dysplastic nevus. The age of the patient, the central anatomic location and the presence of confluent growth of melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction will aid in the correct diagnosis and appropriate surgical excision of these lesions. The main purpose of this study is to raise awareness that in limited biopsies demonstrating the above clinicopathological findings, complete excision of these lesions for further evaluation is recommended.

References

Weedon D . Lentigenes, nevi and melanomas. In: Weedon D (ed). Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, 2002, pp 803–858.

Kossard S, Commens C, Symons M, et al. Lentiginous dysplastic naevi in the elderly: a potential precursor for malignant melanoma. Australas J Dermatol 1991;32:27–37.

Clark Jr WH . A classification of malignant melanoma in man correlated with histogenesis and biological behavior. In: Montagna W, Hu F (eds). Advances in the Biology of the Skin, Vol. VIII. Pergamon Press: New York, 1967, pp 621–647.

Clark Jr WH, Elder DE, Van Horn M . The biological forms of malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol 1984;17:443–450.

Clark Jr WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res 1969;29:705–727.

McGovern VJ, Mihm Jr MC, Bailly C, et al. The classification of malignant melanoma and its histologic reporting. Cancer 1973;32:1446–1457.

Lund HZ, Stobbe GD . The natural history of the pigmented nevus; factors of age and anatomic location. Am J Pathol 1949;15:1117–1155.

Maize JC, Foster G . Age-related changes in melanocytic naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol 1979;4:49–58.

Winkelmann RK, Rocha G . The dermal nevus and statistics: an evaluation of 1200 pigmented lesions. Arch Dermatol 1962;86:310–315.

Blessing K, Husain A, Coburn P . ‘Benign Naevi’ in older individuals: diagnostic difficulties. J Pathol 1998;186:35A.

Blessing K . Benign atypical naevi: diagnostic difficulties and continued controversy. Histopathology 1999;34:189–198.

Kossard S . Atypical lentiginous junctional naevi of the elderly and melanoma. Vincent McGovern Oration. Australas J Dermatol 2002;43:93–101.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Susan Bryant for her help in the manuscript preparation and performing the immunohistochemical studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, R., Page, R., Googe, P. et al. Lentiginous melanoma: a histologic pattern of melanoma to be distinguished from lentiginous nevus. Mod Pathol 18, 1397–1401 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800454

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800454

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Parakeratosis and pagetoid melanocytosis in the evaluation of dysplastic nevi and melanoma

Archives of Dermatological Research (2022)