Abstract

To clarify the significance of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in the development of medullary-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma, we studied the status of promoter methylation and hMLH1 expression in 23 medullary-type and 12 pleomorphic-type carcinomas, as well as the pathology and microsatellite status. In medullary-type carcinomas, the percentages of cases with promoter methylation (83%) and an absence of hMLH1 expression (91%) were significantly higher than in pleomorphic-type carcinomas (14 and 17%), respectively. The rate of microsatellite instability in the medullary type was significantly higher than that of the pleomorphic type (87 vs 40%, P<0.01). Compared with pleomorphic-type carcinomas, medullary-type carcinomas were significantly associated with hMLH1 promoter methylation, absent expression of hMLH1 protein, microsatellite instability, as well as a proximal location, a Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction, a low incidence of lymph node metastasis, and a favorable outcome. Medullary-type carcinomas accumulated with advancing age, especially in the female. These results indicated that hMLH1 hypermethylation, concurrent with a lack of its protein expression, may play an important role in the development of medullary-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas in the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In the large intestine, adenocarcinoma composed of cuboidal epithelial cells showing minimal or no glandular differentiation is defined as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.1, 2, 3 Poorly differentiated lesions are heterogeneous with respect to their clinicopathologic and molecular features.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 A peculiar type of poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma has been recently recognized and termed either medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma,4, 6, 9, 10 solid-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma,5 or large cell minimally differentiated carcinoma.11 Histologically, the tumor is characterized by a small uniform population of tumor cells with fine chromatin and prominent nucleoli. The tumor cells grow in solid sheets and trabeculae, often associated with a prominent intratumoral and/or peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration. The main clinicopathologic features of the tumor are its predominant occurrence in elderly women, a location of the proximal colon, and a relatively favorable prognosis in spite of the high-grade histological features.4, 6, 10 Furthermore, recent molecular studies demonstrate that medullary-type carcinomas show a diploid DNA pattern, a high frequency of microsatellite instability, and low p53 expression.4, 10

Cancers with high levels of microsatellite instability are the hallmark of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, and microsatellite instability occurs in 10–15% of sporadic colorectal carcinomas. Colorectal adenocarcinomas with microsatellite instability often show an absence of hMLH1 protein,12, 13, 14 indicating that the tumor with microsatellite instability may be induced by an abnormality of the mismatch repair gene. A germline mutation has been detected in the mismatch repair gene in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, and hypermethylation has been found in the hMLH1 gene promoter in sporadic colorectal cancer.13 The spread of methylation in the hMLH1 promoter is closely associated with age and the development of sporadic colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability.15

Mucinous or poor differentiation and stromal inflammatory reactions are frequent features of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in which germline mutations of mismatch repair genes cause genetic instability. A link exists between such histological features and somatic genetic instability, consistent with a mutator phenotype, in nonfamilial colorectal cancer.16 However, there are few reports investigating a relationship between medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and methylation of the hMLH1 promoter. In the present study, we focused on investigating this possible relationship and examined 35 cases of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, including 23 medullary-type carcinomas in the elderly.

Materials and methods

Patients

In all, 35 cases, aged 65 years or older with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the large intestine, were selected from the list of colorectal cancers at a geriatric hospital. They were composed of 13 men and 22 women, with an average age of 78 years, ranging from 65 to 99 years old. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease or belonging to families with evidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (according to the Amsterdam criteria), or familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded from the present study. This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Medical Center.

Histopathological Evaluation

All tissue samples were fixed with 10% formalin after resection and then embedded in paraffin in a standard procedure. Serial sections, 3 and 10 μm thick, were prepared for each specimen. The 3 μm-thick section was used for hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunostaining, and the 10 μm-thick section was used for DNA extraction.

All of the tumors were pathologically diagnosed as poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas.1, 2, 3 The 35 cases were classified into two types, medullary and pleomorphic types, according to the description by Ruschoff et al.4 The medullary type of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma was composed of solid sheets or trabeculae of small- to medium-sized quite uniform cells with a variable amount of eosinophilic or amphophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1a). The nuclei were round to oval, regular, with slight or moderate pleomorphism, and a single nucleolus. Occasional cells with more voluminous nuclei were observed in some tumors. The tumor grew expansively with prominent intra- and peritumoral inflammatory cell infiltration and/or a Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction.17 On the other hand, the pleomorphic-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma was composed of solid sheets of medium- to large-sized variable cells with a variable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1b). The tumor cells demonstrated large irregular nuclei with a few irregular nucleoli, coarse chromatin, atypical mitoses, and an infiltrative growth pattern.

Histology of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the large intestine in the elderly. (a) Medullary-type carcinoma (case 2) showing small uniform tumor cells. (b) Pleomorphic-type carcinoma (case 10) showing tumor cells with atypia. Both figures show the same magnification. Hematoxylin–eosin staining.

DNA Extraction

Three 10-μm sections on glass slides were deparaffinized with xylene, rinsed in 100, 90, and 80% ethanol, and briefly stained with hematoxylin. The tissues of the tumor were scraped from the semi-dried section with a blade under the stereomicroscope. When a lesion was histologically heterogeneous (ie a tumor containing well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and/or adenoma as well as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma), DNA was extracted separately from each individual area under the stereomicroscope. DNA samples from normal colorectal tissue were also extracted. The tissue sample was transferred into a sterile 1.5 ml microtube. DNA was extracted from all of these samples by a phenol–chloroform procedure.

Microsatellite Instability

We screened for microsatellite instability using the mononucleotide repeats BAT-26 and BAT-40 according to protocols described by other investigators.18, 19 These probes are sensitive and recommended for the detection of microsatellite-unstable tumors, especially in case of high-frequency microsatellite instability. The cases where bands of different molecular weights were observed in the tumor DNA, but not observed in normal DNA, were designated as microsatellite-unstable.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of hMLH1 Proteins

The expression of hMLH1 proteins was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by treatment with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 15 min. The sections for hMLH1 proteins were heated at 100°C for 10 min to retrieve antigen. Slides were immunostained by the streptavidin–biotin method using an anti-human MLH1 monoclonal antibody (G168-15, PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and developed with diaminobenzidine substrate. Counterstaining was hematoxylin. For hMLH1 protein, adjacent normal tissues were used as internal controls. The intensity of nuclear staining in the entire tumor was classified as negative, weakly positive, and strongly positive in comparison with that of normal tissues. Focal or heterogeneous staining patterns were also recorded. For the statistical analysis, weak or focal staining was counted as negative for hMLH1.

Methylation Study (Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis, COBRA Method)

Bisulfite treatment was performed using a CpGenome DNA Modification Kit (Oncor, Gaithersburg, USA) according to the manufacturer. The COBRA protocol was performed as described previously.20 Bisulfite-modified DNA was amplified by nested PCR with specific primers for the hMLH1 promoter. The primer sequences used for primary and secondary PCR amplification of hMLH1 were described previously.20 Primary PCR was performed in 25 μl reaction mixtures as follows: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final 10 min extension at 72°C. Secondary PCR was performed in 25 μl reaction mixtures as follows: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 63°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final 10 min extension at 72°C. The PCR products were then digested with a specific restriction enzyme, RsaI for at least 2 h and then electrophoresed on 15% polyacrylamide gels.

Statistical Analysis

All data were subjected to statistical analysis. Comparisons among continuous and categorical variables were made using the Students t-test, χ2 or Fisher's exact probability test. A probability value of less than 0.05 (two-sided) was considered to be significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic Findings

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas of the proximal colon (proximal to the splenic flexure) in women accounted for 91% of the cases, being significantly higher than in men (62%, P<0.05). The incidence rate of proximal colonic cancers increased with advancing age, reaching 100% in patients aged over 85 years. Although no significant difference in site distribution was found among any age groups, a higher proportion of proximal colonic cancer was noted with advancing age. The mean size of the poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, including the accompanying neoplastic lesion, was 9.1 cm (ranging from 1.5 to 12.5 cm). Macroscopically, all cases showed ulcerative-invasive features.

Histologically, medullary, and pleomorphic types of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas accounted for 23 and 12 cases, respectively (Figure 1). In medullary-type carcinomas, glandular differentiation was absent in 11 cases and minimal (<5%) in five cases, whereas in seven cases more extensive features of glandular differentiation were observed. Glandular differentiation was mainly represented by the occurrence of a mucosal layer or well-formed glandular structures within the solid sheets. Crohn's-like lymphoid reactions and/or intensive lymphocytic infiltration in the tumor stroma were detected in 18 cases.

On the other hand, in the pleomorphic-type carcinomas glandular differentiation was absent in eight cases and minimal in four cases. None of the tumors showed more extensive features of glandular differentiation. A Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction was found in five cases of the pleomorphic type.

The mean age at diagnosis in the medullary type was significantly higher than that in the pleomorphic type (80.6 vs 73.6 years). Although both types of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma were staged as pT3 or pT4 at the time of surgery, medullary-type carcinomas exhibited significantly less frequent lymph node metastasis (43.5 vs 83.3%, P=0.03). The mortality rate (20%) of patients with medullary-type carcinomas was significantly lower than that (71%) with pleomorphic-type carcinomas (P=0.03). Corresponding to these data, patients with medullary-type carcinomas had a more favorable outcome.

Immunohistochemistry

In all, 24 cancer specimens (69%) showed an absence of hMLH1 protein expression (Figure 2), while the remaining 11 cancer specimens showed positive nuclear hMLH1 staining. All the adjacent normal tissues, including the 24 cases with absent hMLH1 expression, exhibited nuclear hMLH1 expression. Of the 24 tumors 23 with absent hMLH1 expression were located in the proximal colon.

Immunohistochemistry of hMLH1 expression in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. (a) Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma showing no hMLH1 protein expression, with peritumoral infiltration of hMLH1-positive lymphocytes (case 8). (b) Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma showing positive nuclear staining of hMLH1 protein in cancer cells (case 9). Counterstaining, hematoxylin.

Microsatellite Analysis

Representative microsatellite instability is shown in Figure 3. Of the 35 cases 24 were microsatellite-unstable (69%), and 11 were microsatellite-stable (31%). Of the 24 microsatellite-unstable cases, 13 cases showed the instability of only one marker and 11 cases showed the instability of both markers. In all, 20 (83%) of the microsatellite-unstable cases were medullary-type carcinomas, while only three (27%) of the microsatellite-stable cases were medullary-type carcinomas (P<0.01).

Methylation of hMLH1 Gene Promoter

Of the 35 poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas examined, methylation status was determined in 26 cases. Totally, 16 cancers (62%) presented with hMLH1 methylation (Figure 4). Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter was found in 14 of 18 cancers with absent hMLH1 protein expression, but only two in nine cancers with normal hMLH1 expression exhibited methylation, demonstrating a close correlation of transcriptional loss with hMLH1 methylation (P=0.009).

Associations among Microsatellite Instability, hMLH1 Expression and Methylation Status of hMLH1 Promoter

Table 1 demonstrates the hMLH1 expression and methylation status of the hMLH1 promoter in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with or without microsatellite instability. The absence of hMLH1 protein expression (92%) concurrent with hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter (71%) in microsatellite-unstable cases was significantly higher than those (9 and 25%) in microsatellite-stable cases (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively). Microsatellite-unstable cases were significantly correlated with medullary-type carcinoma (P<0.01). The mortality rate was significantly correlated with microsatellite instability (P<0.01), but not with hMLH1 promoter methylation (P=0.09) or hMLH1 expression (P=0.22). Microsatellite-unstable cases showed a favorable outcome.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Medullary-type and Pleomorphic-type Poorly Differentiated Adenocarcinomas

The clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics of medullary-type carcinomas were compared with those of pleomorphic-type carcinomas (Table 2). Significantly different pathologic and molecular features of medullary-type carcinomas occurred in the elderly such as proximal location, more frequent Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction, low incidence of lymph node metastasis, absent hMLH1 expression, microsatellite instability, hMLH1 promoter methylation, and less frequent mortality from the colorectal cancer.

Age-related Alterations of Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Poorly Differentiated Adenocarcinomas

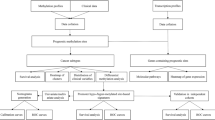

As a result of the stratification of cases according to their ages, medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, concurrent with absent hMLH1 expression and methylation of the hMLH1 promoter, was observed to accumulate with advancing age (Figure 5). Patients aged more than 80 years old with poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma were all female, and patients over 85 years of age all showed medullary-type carcinomas.

Age-related accumulation of medullary-type carcinoma with microsatellite instability, absent hMLH1 protein expression, and hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter. All cases are listed in order of age. (a) M, male; F, female. (b) C, cecum; A, ascending colon; T, transverse colon; D, descending colon; S, sigmoid colon; R, rectum. (c) ▪, medullary-type carcinoma; □, pleomorphic-type carcinoma. (d) ▪, microsatellite-unstable; □, microsatellite-stable. (e) ▪, absent expression of hMLH1 protein; □, normal expression. (f) ▪, methylated hMLH1 promoter; □, unmethylated hMLH1 promoter; ND, not determined.

Discussion

We have shown that in the elderly, approximately two-thirds of poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas have clinicopathologic features of a medullary phenotype. Additionally, hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter with an absence of hMLH1 protein expression is closely correlated with medullary-type carcinomas with microsatellite instability in the elderly.

The present study has provided evidence that medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas showed microsatellite instability associated with absent hMLH1 expression and hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter. Most of the medullary-type carcinomas showed a high proportion of microsatellite instability in comparison with pleomorphic-type carcinomas. This result is in accord with that of other investigators.4, 10, 14 Although the high incidence of absent hMLH1 expression was reported in poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas,14 our results indicated that in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, the medullary-type carcinoma is primarily affected as compared with pleomorphic-type carcinoma. In view of the histopathological type of tumor, we are the first to describe hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in medullary-type carcinomas. The molecular event was detected in sporadic colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability,13, 21 and caused inactivation of the hMLH1 gene, resulting in absent expression of its protein.13 These results suggest that hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter is the underlying cause of the mismatch repair defects observed in medullary-type carcinomas. In contrast, pleomorphic-type carcinomas do not seem to be induced by hMLH1 methylation. Thus, these findings indicate that medullary- and pleomorphic-type carcinomas differ not only in their clinicopathologic features but also in their molecular findings and therefore we hypothesize that both types of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas have different pathways in carcinogenesis.4, 14

Medullary-type carcinomas in the elderly share clinicopathologic and biological features with those occurring in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: predominant occurrence in the proximal colon, large-sized tumors, expansive growth, prominent Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction, low incidence of lymph node or hematogenous metastasis, and favorable outcome.22 Common features are tumor location, histology, and biological behavior while age, gender distribution, and the presence of extra-colorectal primary malignancies are different between the two. Genetically, four human mismatch repair genes, hMSH2, hMLH1, hMSH6, and hPMS2, are involved in 47, 47, <5 and <1% of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, respectively. Mutations in such genes result in a ‘mutator phenotype’ that can be identified by observing genetic instability in the form of deletion and insertion mutations in simple repetitive DNA sequences at microsatellite loci. The present study supports the hypothesis that hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter also results in a ‘mutator phenotype’.13, 23 Consequently, medullary-type carcinomas in the elderly may be induced by an epigenetic event within the hMLH1 gene, whereas hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer results from germ-line mutation of the mismatch repair gene with occasional hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter.24

In the present study, medullary-type carcinomas accumulated with advancing age. The spread of methylation in the hMLH1 promoter in the normal colonic mucosa was closely associated with age and with the development of sporadic colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability.15 The frequency of methylation in those tumors was significantly correlated with aging.21, 25 Methylation has been observed not only in the hMLH1 promoter but also in other gene promoters, such as the estrogen receptor (ER), N33, MyoD, etc.26, 27 Furthermore, our previous study showed that age-related methylation was found in gastric cancer as well as colorectal cancer.20 The absent expression of hMLH1 protein was closely related with aging in gastric and colorectal cancers.20, 28 Since aberrant CpG island methylation is a powerful mechanism for the inactivation of gene activity, age-related methylation of the genes may play a significant role in the increase of malignant neoplasms in the elderly.

Age and gender differences exist in colorectal cancers. The proportion of proximal colonic cancer in women was approximately 10% higher than those in men, and increased with advancing age.29 Molecular evidence showed colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability was most frequent among younger male and older female patients.12, 30 The frequency of hMLH1 methylation with lack of its expression was significantly correlated with females and aging.21, 31 These facts may contribute to the observation that medullary-type carcinomas occur more frequently in the older female patient and in the proximal colon.6, 10

The present study has suggested that medullary-type poorly differentiated carcinomas should be distinguished from other adenocarcinomas with minimal or no glandular differentiation due to its biological behavior. Since approximately 90% of medullary-type carcinomas showed an absence of hMLH1 protein expression together with microsatellite instability, immunohistochemistry for the detection of hMLH1 protein may be useful in predicting the tumor type.12, 32 However, immunohistochemistry cannot replace testing for microsatellite instability to identify microsatellite-unstable sporadic colorectal cancer,33 and morphological prediction of microsatellite-unstable cancer has low sensitivity.34 Thus, we emphasize that both hMLH1 immunohistochemistry and a histopathological evaluation can predict medullary-type carcinomas, but they may miss some cases.32, 33 Molecular analysis is required for therapeutic decisions.34

Colorectal adenocarcinoma are graded predominantly on the basis of the extent of glandular appearances.2, 3 They are divided into well, moderately, and poorly differentiated, and in general the differentiation may reflect a biological behavior. Although medullar-type carcinoma is classified as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma,3 several reports, together with our data, demonstrated that medullary-type carcinoma showed a favorable prognosis.4, 6, 10 The mortality rates in medullary-type carcinoma vs in well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma are unclear, but warrant further examination.

In conclusion, we found an age-related accumulation of medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in the elderly, especially in females, as well as hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter with absent hMLH1 protein expression, which may play an important role in carcinogenesis of the tumor.

References

Jass JR, Sobin LH . Histological Typing of Intestinal Tumours. Berlin, Germany; Springer-Verlag, 1989.

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma, First English Edition. Kanehara: Tokyo, Japan, 1997.

Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, et al. WHO histological classification of tumours of the colon and rectum. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2000, pp 103–143.

Ruschoff J, Dietmaier W, Luttges J, et al. Poorly differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma, medullary type: clinical, phenotypic, and molecular characteristics. Am J Pathol 1997;150:1815–1825.

Sugao Y, Yao T, Kubo C, et al. Improved prognosis of solid-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 1997;31:123–133.

Jessurun J, Romero-Guadarrama M, Manivel JC . Medullary adenocarcinoma of the colon: clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Hum Pathol 1999;30:843–848.

Nakahara H, Ishikawa T, Itabashi M, et al. Diffusely infiltrating primary colorectal carcinoma of linitis plastica and lymphangiosis types. Cancer 1992;69:901–906.

Burke AB, Shekitka KM, Sobin LH . Small cell carcinomas of the large intestine. Am J Clin Pathol 1991;95:315–321.

Kim H, Jen J, Vogelstein B, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of sporadic colorectal carcinomas with DNA replication errors in microsatellite sequences. Am J Pathol 1994;145:148–156.

Lanza G, Gafa R, Matteuzzi M, et al. Medullary-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the large bowel: a distinct clinicopathologic entity characterized by microsatellite instability and improved survival. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2429–2438.

Hinoi T, Tani M, Lucas PC, et al. Loss of CDX2 expression and microsatellite instability are prominent features of large cell minimally differentiated carcinomas of the colon. Am J Pathol 2001;159:2239–2248.

Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Cunningham JM, et al. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: different mutator phenotypes and the principal involvement of hMLH1. Cancer Res 1998;58:1713–1718.

Cunningham JM, Christensen ER, Tester DJ, et al. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res 1998;58:3455–3460.

Gafa R, Maestri I, Matteuzzi M, et al. Sporadic colorectal adenocarcinomas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Cancer 2000;89:2025–2037.

Nakagawa H, Nuovo GJ, Zervos EE, et al. Age-related hypermethylation of the 5′ region of MLH1 in normal colonic mucosa is associated with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer development. Cancer Res 2001;61:6991–6995.

Risio M, Reato G, di Celle PF, et al. Microsatellite instability is associated with the histological features of the tumor in nonfamilial colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1996;56:5470–5474.

Graham DM, Appelman HD . Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction and colorectal carcinoma: a potential histologic prognosticator. Mod Pathol 1990;3:332–335.

Cravo M, Lage P, Albuquerque C, et al. BAT-26 identifies sporadic colorectal cancers with mutator phenotype: a correlative study with clinico-pathological features and mutations in mismatch repair genes. J Pathol 1999;188:252–257.

Zhou XP, Hoang JM, Cottu P, et al. Allelic profiles of mononucleotide repeat microsatellites in control individuals and in colorectal tumors with and without replication errors. Oncogene 1997;15:1713–1718.

Nakajima T, Akiyama Y, Shiraishi J, et al. Age-related hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in gastric cancers. Int J Cancer 2001;94:208–211.

Miyakura Y, Sugano K, Konishi F, et al. Extensive methylation of hMLH1 promoter region predominates in proximal colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1300–1309.

Jass JR . Pathology of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci 2000;910:62–73.

Toyota M, Ohe-Toyota M, Ahuja N, et al. Distinct genetic profiles in colorectal tumors with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:710–715.

Young J, Simms LA, Biden KG, et al. Features of colorectal cancers with high-level microsatellite instability occurring in familial and sporadic settings: parallel pathways of tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol 2001;159:2107–2116.

Hawkins N, Norrie M, Cheong K, et al. CpG island methylation in sporadic colorectal cancers and its relationship to microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1376–1387.

Issa JP, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, et al. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet 1994;7:536–540.

Ahuja N, Li Q, Mohan AL, et al. Aging and DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa and cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:5489–5494.

Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Thibodeau SN, et al. Frequency of loss of hMLH1 expression in colorectal carcinoma increases with advancing age. Cancer 2003;97:1421–1427.

Arai T, Takubo K, Sawabe M, et al. Pathologic characteristics of colorectal cancer in the elderly: a retrospective study of 947 surgical cases. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;31:67–72.

Breivik J, Lothe RA, Meling GI, et al. Different genetic pathways to proximal and distal colorectal cancer influenced by sex-related factors. Int J Cancer 1997;74:664–669.

Malkhosyan SR, Yamamoto H, Piao Z, et al. Late onset and high incidence of colon cancer of the mutator phenotype with hypermethylated hMLH1 gene in women. Gastroenterology 2000;119:598.

Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, et al. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1043–1048.

Salahshor S, Koelble K, Rubio C, et al. Microsatellite instability and hMLH1 and hMSH2 expression analysis in familial and sporadic colorectal cancer. Lab Invest 2001;81:535–541.

Alexander J, Watanabe T, Wu TT, et al. Histopathological identification of colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol 2001;158:527–535.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff in the Department of Pathology, Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Medical Center for their excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arai, T., Esaki, Y., Sawabe, M. et al. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter with absent hMLH1 expression in medullary-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma in the elderly. Mod Pathol 17, 172–179 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800018

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800018

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Estrogen concentration and estrogen receptor-β expression in postmenopausal colon cancer considering patient/tumor background

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Mismatch repair proteins immunohistochemical null phenotype in colon medullary carcinoma

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2021)

-

Clinicopathological importance of colorectal medullary carcinoma

European Surgery (2019)

-

Histopathologic risk stratification of stage IIB colorectal cancer

Surgery Today (2017)

-

The Increasing Relevance of Tumour Histology in Determining Oncological Outcomes in Colorectal Cancer

Current Colorectal Cancer Reports (2015)