Abstract

Adult stem cells reside in adult tissues and serve as the source for their specialized cells. In response to specific factors and signals, adult stem cells can differentiate and give rise to functional tissue specialized cells. Adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have the potential to differentiate into various mesenchymal lineages such as muscle, bone, cartilage, fat, tendon and ligaments. Adult MSCs can be relatively easily isolated from different tissues such as bone marrow, fat and muscle. Adult MSCs are also easy to manipulate and expand in vitro. It is these properties of adult MSCs that have made them the focus of cell-mediated gene therapy for skeletal tissue regeneration. Adult MSCs engineered to express various factors not only deliver them in vivo, but also respond to these factors and differentiate into skeletal specialized cells. This allows them to actively participate in the tissue regeneration process. In this review, we examine the recent achievements and developments in stem-cell-based gene therapy approaches and their applications to bone, cartilage, tendon and ligament tissues that are the current focus of orthopedic medicine.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Odorico JS, Kaufman DS, Thomson JA . Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells 2001; 19: 193–204.

Jiang Y et al. Multipotent progenitor cells can be isolated from postnatal murine bone marrow, muscle, and brain. Exp Hematol 2002; 30: 896–904.

Labat ML . Stem cells and the promise of eternal youth: embryonic versus adult stem cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2001; 55: 179–185.

Martin JA, Buckwalter JA . Aging, articular cartilage chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis. Biogerontology 2002; 3: 257–264.

Martin JA, Buckwalter JA . Human chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis. Biorheology 2002; 39: 145–152.

Prockop DJ . Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science 1997; 276: 71–74.

Pittenger MF et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999; 284: 143–147.

Liechty KW et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med 2000; 6: 1282–1286.

Jankowski RJ, Deasy BM, Huard J . Muscle-derived stem cells. Gene Therapy 2002; 9: 642–647.

Gazit D et al. Engineered pluripotent mesenchymal cells integrate and differentiate in regenerating bone: a novel cell-mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med 1999; 1: 121–133.

Turgeman G et al. Systemically administered rhBMP-2 promotes MSC activity and reverses bone and cartilage loss in osteopenic mice. J Cellular Biochem 2002; 86: 461–474.

Lieberman JR et al. Regional gene therapy with a BMP-2-producing murine stromal cell line induces heterotopic and orthotopic bone formation in rodents. J Orthop Res 1998; 16: 330–339.

Lou J, Xu F, Merkel K, Manske P . Gene therapy: adenovirus-mediated human bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transfer induces mesenchymal progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Orthop Res 1999; 17: 43–50.

Engstrand T et al. Transient production of bone morphogenetic protein 2 by allogeneic transplanted transduced cells induces bone formation. Hum Gene Ther 2000; 11: 205–211.

Lieberman JR et al. The effect of regional gene therapy with bone morphogenetic protein-2-producing bone-marrow cells on the repair of segmental femoral defects in rats. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81: 905–917.

Wozney JM . Overview of bone morphogenetic proteins. Spine 2002; 27S: 2–8.

Ebara S, Nakayama K . Mechanism for the action of bone morphogenetic proteins and regulation of their activity. Spine 2002; 27S: 10–15.

Wozney JM et al. Novel regulation of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science 1988; 242: 1528–1534.

Wang EA et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein induces bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87: 2220–2224.

Volek-Smith H, Urist MR . Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP) induces heterotopic bone development in vivo and in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1996; 211: 265–272.

Yamaguchi A et al. Effects of BMP-2, BMP-4, and BMP-6 on osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow derived stromal cell lines, ST2, and MC3T3-G2/PA6. Biochem Biophysiol Res Commun 1996; 220: 366–371.

Chaudhari A, Ron E, Rethman MP . Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates differentiation in primary cultures of fetal rat clavarial osteoblasts. Mol Cell Biochem 1997; 167: 31–39.

Hanada K, Dennis JE, Caplan AJ . Stimulatory effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Mineral Res 1997; 12: 1606–1614.

Lacenda F, Avioli LV, Cheng SL . Regulation of bone matrix protein expression and induction of differentiation of human osteoblasts and human bone marrow stromal cells by bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Cell Biochem 1997; 67: 386–396.

Fromigue O, Marie PJ, Lomri A . Bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor-beta2 interact to modulate human bone marrow stromal cell proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Biochem 1998; 68: 411–426.

Gori F et al. Differentiation of human marrow stromal cells: bone morphogenetic protein-2 increases OSF2/CBFA1, enhances osteoblast commitment and inhibits late adipocyte maturation. J Bone Mineral Res 1999; 14: 1522–1534.

Gysin R et al. Ex vivo gene therapy with stromal cells transduced with a retroviral vector containing the BMP4 gene completely heals. Gene Therapy 2002; 9: 991–999.

Wright V et al. BMP4-expressing muscle-derived stem cells differentiate into osteogenic lineage and improve bone healing in immunocompetent mice. Mol Ther 2002; 6: 169–178.

Peng H et al. Synergistic enhancement of bone formation and healing by stem cell-expressed VEGF and bone morphogenetic protein-4. J Clin Invest 2002; 110: 751–759.

Chen Y et al. In vivo new bone formation by direct transfer of adenoviral-mediated bone morphogenetic protein-4 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002; 298: 121–127.

Dumont RJ et al. Ex vivo bone morphogenetic protein-9 gene therapy using human mesenchymal stem cells induces spinal fusion in rodents. Neurosurgery 2002; 51: 1239–1244.

Valentin-Opran A et al. Clinical evaluation of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Clin Orthop 2002; 395: 110–120.

Yoon ST, Boden SD . Osteoinductive molecules in orthopaedics: basic science and preclinical studies. Clin Orthop 2002; 395: 33–43.

Moutsatsos IK et al. Exogenously regulated stem cell mediated gene therapy for bone regeneration. Mol Ther 2001; 3: 449–461.

Turgeman G et al. Engineered human mesenchymal stem cells: a novel platform for skeletal cell mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med 2001; 3: 240–251.

Oreffo RO, Virdi AS, Triffitt JT . Retroviral marking of human bone marrow fibroblasts: in vitro expansion and localization in calvarial sites after subcutaneous transplantation in vivo. J Cell Physiol 2001; 186: 201–209.

Bruder SP et al. Bone regeneration by implantation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res 1998; 16: 155–162.

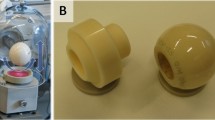

Mankani MH et al. In vivo bone formation by human bone marrow stromal cells: effect of carrier particle size and shape. Biotechnol Bioeng 2001; 72: 96–101.

Laurencin CT et al. Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)/hydroxyapatite delivery of BMP-2-producing cells: a regional gene therapy approach to bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2001; 22: 1271–1277.

Lee JY et al. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2-expressing muscle-derived cells on healing of critical-sized bone defects in mice. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83: 1032–1039.

Musgrave DS et al. Human skeletal muscle cells in ex vivo gene therapy to deliver bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 120–127.

Young BH, Peng H, Huard J . Muscle-based gene therapy and tissue engineering to improve bone healing. Clin Orthop 2002; 403S: 243–251.

Skillington J, Choy L, Derynck R . Bone morphogenetic protein and retinoic acid signaling cooperate to induce osteoblast differentiation of preadipocytes. J Cell Biol 2002; 159: 135–146.

De Ugarte DA et al. Comparison of multi-lineage cells from human adipose tissue and bone marrow. Cells Tissues Organs 2003; 174: 101–109.

Dragoo JL et al. Bone induction by BMP-2 transduced stem cells derived from human fat. J Orthop Res 2003; 21: 622–629.

Wobus AM, Boheler KR . Embryonic stem cells as developmental model in vitro. Preface. Cells Tissues Organs 1999; 165: 129–130.

Phillips BW et al. Compactin enhances osteogenesis in murine embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 284: 478–484.

Robertson JA . Human embryonic stem cell research: ethical and legal issues. Nat Rev Genet 2001; 2: 74–78.

Jiang Y et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 2002; 418: 41–49.

Gerber HP et al. VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nat Med 1999; 5: 623–628.

Yamashita H et al. Growth/differentiation factor-5 induces angiogenesis in vivo. Exp Cell Res 1997; 235: 218–226.

Yang X et al. Angiogenesis defects and mesenchymal apoptosis in mice lacking SMAD5. Development 1999; 126: 1571–1580.

Kassem M . The type I/type II model for involutional osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J (eds). Osteoporosis. Academic Press: New York, 1996, pp 691–702.

Notelovitz M . Estrogen therapy and osteoporosis: principles & practice. Am J Med Sci 1997; 313: 2–12.

Gazit D, Zilberman Y, Ebner R, Kahn AJ . Bone loss (osteopenia) in old male mice results from diminished activity and availability of TGF-beta. J Cell Biochem 1998; 70: 478–488.

Gazit D et al. Recombinant TGF-β1 stimulates bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells activity and bone matrix synthesis in osteopenic old male mice. J Cell Biochem 1999; 73: 379–389.

Byers RJ, Hoyland JA, Braidman IP . Osteoporosis in men: a cellular endocrine perspective of an increasingly common clinical problem. J Endocrinol 2001; 168: 353–362.

Zhou S et al. Estrogen modulates estrogen receptor alpha and beta expression, osteogenic activity and apoptosis in mesenchymal stem cells (AMSCs) of osteoporotic mice. J Cell Biochem 2001; 81: 144–155.

Goater JJ et al. Efficacy of ex vivo OPG gene therapy in preventing wear debris induced osteolysis. J Orthop Res 2002; 20: 169–173.

Yudoh K et al. Reconstituting telomerase activity using the telomerase catalytic subunit prevents the telomere shorting and replicative senescence in human osteoblasts. J Bone Mineral Res 2001; 16: 1453–1464.

Murray JF . Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 1999, pp 367–370.

Abboud SL et al. Rescue of the osteopetrotic defect in op/op mice by osteoblast-specific targeting of soluble colony-stimulating factor-1. Endocrinology 2002; 143: 1942–1949.

Niyibizi C et al. Transfer of proalpha2(I) cDNA into cells of a murine model of human osteogenesis imperfecta restores synthesis of type I collagen comprised of alpha1(I) and alpha2(I) heterotrimers in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Biochem 2001; 83: 84–91.

Kuhlcke K et al. Highly efficient retroviral gene transfer based on centrifugation-mediated vector preloading of tissue culture vessels. Mol Ther 2002; 5: 473–478.

Kalajzic I et al. Use of VSV-G pseudotyped retroviral vectors to target murine osteoprogenitor cells. Virology 2001; 284: 37–45.

Liu P et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells are efficiently transduced by vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped retrovectors without affecting subsequent osteoblastic differentiation. Bone 2001; 29: 331–335.

Peng H et al. Development of an MFG-based retroviral vector system for secretion of high levels of functionally active human BMP4. Mol Ther 2001; 4: 95–104.

Stover ML et al. Bone-directed expression of Col1a1 promoter-driven self-inactivating retroviral vector in bone marrow cells and transgenic mice. Mol Ther 2001; 3: 543–550.

Walsh DA, Haywood L . Angiogenesis: a therapeutic target in arthritis. Curr Opin Invest Drugs 2001; 2: 1054–1063.

Fernandes JC, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP . The role of cytokines in osteoarthritis. Pathophysiology 2002; 39: 237–246.

Aigner T, Kim HA . Apoptosis and cellular vitality. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 1986–1996.

Robbins PD, Evans CH, Chernajovsky Y . Gene therapy for arthritis. Gene Therapy 2003; 10: 902–911; Review.

Dayer JM . The pivotal role of interleukin-1 in the clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42 (Suppl 2): ii3–ii10; Review.

Nixon AJ et al. Insulin like growth factor-I gene therapy applications for cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Related Res 2000; 379S: 201–213.

Saxer RA et al. Gene mediated insulin-like growth factor-I delivery to the synovium. J Orthop Res 2001; 19: 759–767.

Brower-Toland BD et al. Direct adenovirus-mediated insulin-like growth factor I gene transfer enhances transplant chondrocyte function. Hum Gene Ther 2001; 12: 117–129.

Lee KH et al. Regeneration of hyaline cartilage by cell-mediated gene therapy using transforming growth factor B1-producing fibroblasts. Hum Gene Ther 2001; 12: 1805–1813.

Gelse K et al. Fibroblast-mediated delivery of growth factor complementary DNA into mouse joints induces chondrogenesis but avoids the disadvantages of direct viral gene transfer. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44: 1943–1953.

Bianco P, Riminucci M, Gronthos S, Robey PG . Bone marrow stromal stem cells: nature, biology, and potential applications. Stem Cells 2001; 19: 180–192.

Mason JM et al. Cartilage and bone regeneration using gene-enhanced tissue engineering. Clin Orthop Related Res 2000; 379S: 171–178.

Adachi N et al. Muscle derived, cell based ex vivo gene therapy for treatment of full thickness articular cartilage defects. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 1920–1930.

Kramer J et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived chondrogenic differentiation in vitro: activation by BMP-2 and BMP-4. Mech Dev 2000; 92: 193.

Akiyama H et al. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev 2002; 16: 2813–2828.

Fischer L, Boland G, Tuan RS . Wnt-3A enhances bone morphogenetic protein-2-mediated chondrogenesis of murine C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 30870–30878.

Hoffmann A et al. The T-box transcription factor Brachyury mediates cartilage development in mesenchymal stem cell line C3H10T1/2. J Cell Sci 2002; 15: 769–781.

Chimich D et al. The effects of initial end contact on medial collateral ligament healing: a morphological and biomechanical study in a rabbit model. J Orthop Res 1991; 9: 37–47.

Thornton GM, Leask GP, Shrive NG, Frank CB . Early medial collateral ligament scars have inferior creep behaviour. J Orthop Res 2000; 18: 238–246.

Martinek V et al. Enhancement of tendon–bone integration of anterior cruciate ligament grafts with bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transfer: a histological and biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84: 1123–1131.

Lou J, Xu F, Merkel K, Manske P . Gene therapy: adenovirus-mediated human bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transfer induces mesenchymal progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Orthop Res 1999; 17: 43–50.

Lou J et al. BMP-12 gene transfer augmentation of lacerated tendon repair. J Orthop Res 2001; 19: 1199–1202.

Helm GA et al. A light and electron microscopic study of ectopic tendon and ligament formation induced by bone morphogenetic protein-13 adenoviral gene therapy. J Neurosurg 2001; 95: 298–307.

Inada M et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-12 and -13 inhibit terminal differentiation of myoblasts, but do not induce their differentiation into osteoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996; 222: 317–322.

Day CS et al. Myoblast-mediated gene transfer to the joint. J Orthop Res 1997; 15: 894–903.

Menetrey J et al. Direct-, fibroblast- and myoblast-mediated gene transfer to the anterior cruciate ligament. Tissue Eng 1999; 5: 435–442.

Gooch KJ et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins-2, -12, and-13 modulate in vitro development of engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng 2002; 8: 591–601.

Lodie TA et al. Systematic analysis of reportedly distinct populations of multipotent bone marrow-derived stem cells reveals a lack of distinction. Tissue Eng 2002; 8: 739–751.

Kuznetsov SA et al. Circulating skeletal stem cells. J Cell Biol 2001; 153: 1133–1140.

Varady P et al. Morphologic analysis of BMP-9 gene therapy-induced osteogenesis. Hum Gene Ther 2001; 12: 697–710.

Viggeswarapu M et al. Adenoviral delivery of LIM mineralization protein-1 induces new-bone formation in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83: 364–376.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gafni, Y., Turgeman, G., Liebergal, M. et al. Stem cells as vehicles for orthopedic gene therapy. Gene Ther 11, 417–426 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302197

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302197

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The ERα/KDM6B regulatory axis modulates osteogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells

Bone Research (2022)

-

RNA-Seq based genetic variant discovery provides new insights into controlling fat deposition in the tail of sheep

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Nucleic acid delivery to mesenchymal stem cells: a review of nonviral methods and applications

Journal of Biological Engineering (2019)

-

Effect of Cr(VI) and Ni(II) metal ions on human adipose derived stem cells

BioMetals (2015)

-

Inhibition of JNK and ERK pathways by SP600125- and U0126-enhanced osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2012)