Abstract

Study design:

Secure, web-based survey.

Objectives:

Elicit specific information about sexual function from men with spinal cord injuries (SCI).

Setting:

World-wide web.

Methods:

Individuals 18 years or older living with SCI obtained a pass-code to enter a secure website and then answered survey questions.

Results:

The presence of genital sensation was positively correlated with the ability to feel a build up of sexual tension in the body during sexual stimulation and in the feeling that mental arousal translates to the genitals as physical sensation. There was an inverse relationship between developing new areas of arousal above the level of lesion and not having sensation or movement below the lesion. A positive relationship existed between the occurrence of spasticity during sexual activity and erectile ability. Roughly 60% of the subjects had tried some type of erection enhancing method. Only 48% had successfully achieved ejaculation postinjury and the most commonly used methods were hand stimulation, sexual intercourse, and vibrostimulation. The most commonly cited reasons for trying to ejaculate were for pleasure and for sexual intimacy. Less than half reported having experienced orgasm postinjury and this was influenced by the length of time postinjury and sacral sparing.

Conclusion:

SCI not only impairs male erectile function and ejaculatory ability, but also alters sexual arousal in a manner suggestive of neuroplasticity. More research needs to be pursued in a manner encompassing all aspects of sexual function.

Sponsorship:

Christopher Reeve Foundation (#36708, KDA); Reeve-Irvine Research Center.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

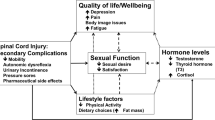

Sexual function is an important part of spinal cord injury (SCI), yet it has traditionally been considered a low priority in regard to research topics and funding. Like many other aspects of SCI, sexual function is influenced by the integrity of motor, sensory, and autonomic pathways as well as by psychological and social factors. There may be debate in the clinical field as to what is considered a sexual ‘dysfunction’, but the simple fact is that sexual impairments occur to some degree in nearly every SCI and individuals living with SCI rate improving sexual function as a high priority to improving quality of life.1, 2

An extensive amount of literature has been published regarding certain aspects of male sexual dysfunction associated with SCI and it is not the intent of this article to be an exhaustive review of those subjects.3, 4, 5, 6 The two most extensively researched areas are erectile dysfunction (ED) and ejaculatory compromise. Briefly, the neurologic injury level and severity have a significant impact on erectile ability and on the occurrence of reflexogenic or psychogenic erections.3, 7 The presence of reflexogenic or psychogenic erections does not necessarily indicate that those erections are rigid enough or can be reliably maintained for sexual intercourse. Several studies have demonstrated that Viagra is a safe and effective treatment for ED in some men with SCI.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Other options for erectile enhancement, aside from various drugs, include penile rings and vacuum devices.14 Data from a small case series suggests that intrathecal infusion of Baclofen for spasticity management may have a negative impact on erectile and ejaculatory ability.15

Ejaculation is a more complicated process and anejaculation results in a significant number of spinal injured men.3 Reflexes, somatic responses, and electrophysiological parameters have been used to try to predict the ability to successfully induce ejaculation.16, 17 Penile vibrostimulation (PVS) and electroejaculation are the two most commonly used methods for inducing ejaculation to collect sperm for fertility purposes.3, 18 Semen retrieved for fertility is not without problems.3 High levels of leukocytes and inflammatory cytokines have been found in the seminal plasma of men with SCI and these have been shown to play a role in reducing sperm motility,19, 20, 21 thus reducing the likelihood of fertilization. Neutralization of specific cytokines by antibody administration has been shown to enhance sperm motility in a recent study involving a small number of subjects.22 There is conflicting evidence as to whether repeated ejaculation via PVS has a beneficial effect on semen quality.23, 24 A significant side effect of assisted ejaculation is that both PVS and electroejaculation can induce autonomic dysreflexia (AD) in men with injuries above T6.25 In some cases, the symptoms of AD can be protracted for several days following an ejaculatory event and this dangerous situation has been termed ‘malignant’ AD.26 Even more dangerous is when the symptoms of AD become ‘silent’, usually during repeated ejaculation, and individuals are not aware of rising blood pressure.27 Another effect of PVS-induced ejaculation is that some men experience reduced spasticity for several hours afterwards.28, 29

Reproduction, however, is not necessarily important to all men with SCI. As demonstrated in the accompanying article,2 intimacy need is the primary driving factor in pursuing sexual relationships for many people in the general community living with SCI. Here, using the same survey instrument, we present detailed information regarding sexual stimulation and arousal in men with SCI and explore the deficits, adaptivity, and/or neuroplasticity that develops with time postinjury. Physical intimacy with a partner is highly dependent on sensations of arousal to stimulation in a sexual context and these factors have seldom been investigated in men with SCI. In this report, we also present a comprehensive analysis of erectile enhancement and reliability, ejaculatory success, and the ability to achieve orgasm.

Methods

Survey design

A general questionnaire covering a wide variety of sexual components was developed to acquire more detailed information related to sexual function after SCI. This questionnaire was not designed to be used as a sexual function outcome measure. Rather, it was designed to query the general SCI population beyond those individuals that actively seek out laboratory research studies or fertility clinics.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections. The first section was answered by males and females and those results are presented in the accompanying manuscript.2 The second section was answered only by males. It contained specific and detailed questions regarding arousal, erection, ejaculation, and orgasm. Analyses were then performed (see Statistics below) to identify how SCI alters male sexual function and the factors that influence sexual response over time. Those data are presented in this manuscript. The third section was completed by females only and those results are presented in the other accompanying manuscript.30 Wherever possible, a list of answers was provided for each question to assist in standardization of responses. Few questions required descriptive answers.

The study was approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Review Board. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. Attached to the survey was an introductory statement explaining the purpose of the survey, directions for participating, the right to privacy, what the results were to be used for, and that three of the five investigators conducting the survey also had spinal cord injuries. This information served as the informed consent statement, as required by the Institutional Review Board.

Participant recruitment

The eligibility requirements for the survey were simply that an individual be eighteen years of age or older and be living with permanent spinal paralysis. Advertisements were placed on multiple SCI websites, online support groups, SCI bulletin boards, etc. (including the National Spinal Cord Injury Association, Project Walk, Reeve-Irvine Research Center, NeuroFitness Foundation, SCI Zone, 360mag, Paralysis Resource Center, Mobile Women, Paralysis Project of America, United Spinal/Orbit magazine, Florida SCI Resource Center, Miami Project E-News, and Canadian Paraplegic Association). Print advertisements were also placed in Paraplegia News, New Mobility, and the California Paralyzed Veterans Association monthly newsletter.

Eligible subjects who were willing to participate received a randomly generated pass code in order to enter the secure website. Upon completion of the survey, the pass code used by an individual to enter the website was not linked to his/her answers, thereby preserving anonymity. Individuals interested in participating whom did not have access to the Internet could receive a paper version of the questionnaire in the mail and then send it back to the lead investigator, who then entered the information into the secure database. The study was open for enrollment for a 6-month time period.

Statistical analyses

Statistical assessments were performed using the JMP 6.0.0 Statistical Discovery™ software package from SAS, with guidance from the UCI Center for Statistical Consulting. Descriptive analyses of the data were performed first. After which, a series of bivariate analyses were performed to determine whether any of the following variables (X) influenced any of the following responses (Y):

X factor

-

1

Current age group (under 30, 30–50, over 50)

-

2

Years postinjury group (0–5, 6–10, >10)

-

3

Injury group (cervical, upper thoracic, lower thoracic, lumbosacral)

-

4

Can you feel touch in the anal area? (yes/no)

-

5

Can you lift your legs against gravity? (yes/no)

-

6

Number of medical conditions (0, 1, 2, 3 or more)

-

7

Reported pain (yes/no)

-

8

Reported depression (yes/no)

-

9

Reported spasticity (yes/no)

-

10

Number of medication types using (0, 1, 2 or more)

-

11

Using spasticity medication (yes/no)

-

12

Using pain medication (yes/no)

-

13

Using bladder medication (yes/no)

-

14

Using recreational drugs (yes/no)

-

15

Current bladder management (controlled voiding, manual crede or spontaneous voiding, indwelling catheter, intermittent catheterization, condom catheter, suprapubic catheter, other)

-

16

Current bowel management (voluntary control, digital stimulation alone, enema±digital stimulation, suppository±digital stimulation, other)

-

17

Do you experience AD during bladder care? (yes/no/sometimes)

-

18

Do you experience AD during bowel care? (yes/no/sometimes)

-

19

Are you concerned about bladder incontinence during sexual activity? (not concerned, undecided, concerned)

-

20

Are you concerned about bowel incontinence during sexual activity? (not concerned, undecided, concerned)

-

21

Do bladder and bowel issues prevent you from seeking sexual activity with partners? (yes/no/sometimes)

-

22

Do you have any genital sensation? (yes/no)

-

23

Were you ever involved in any type of sexual relationship preinjury? (yes/no)

-

24

Have you ever been involved in any type of sexual relationship postinjury? (yes/no)

-

25

Are you currently involved in any type of sexual relationship? (yes/no)

-

26

Do you experience AD during any type of sexual activity (alone or with a partner)? (yes/no)

-

27

How much does AD interfere with your sexual activity? (none/some)

-

28

Do you experience the symptoms of AD as pleasurable/arousing? (yes/no/not applicable)

-

29

Number of physical conditions experienced during sexual activity (0, 1, 2 or more)

-

30

Pain during sexual activity (yes/no)

-

31

Headache during sexual activity (yes/no)

-

32

Tingling sensations during sexual activity (yes/no)

-

33

Spasms during sexual activity (yes/no)

-

34

What is the primary reason you are interested in pursuing sexual activity? (sexual need, intimacy need, self-esteem, fertility, to keep my partner, other)

-

35

Do you agree that you injury has altered you sexual sense of self? (disagree, undecided, agree)

-

36

Is improving your sexual function important to improving your quality of life? (yes/no)

Y response

-

1

Do you feel a build up of sexual tension in your body during sexual stimulation? (yes/no)

-

2

Do you feel a build up of sexual tension in your head during sexual stimulation? (yes/no)

-

3

Do you feel your mental arousal translates to your genitals in physical sensation? (disagree, undecided, agree)

-

4

Difficulty with becoming psychologically aroused (none/some)

-

5

Difficulty with becoming physically aroused (none/some)

-

6

Are you aroused by sensual light stroking of nearby non-genital skin (ex. perineum, inner thigh, etc.)? (yes/no)

-

7

Have you developed new areas of arousal above the level of your lesion? (yes/no)

-

8

Have you developed new areas of arousal at the level of your lesion? (yes/no)

-

9

Aroused by touching genitals (yes/no)

-

10

Aroused by head/neck stimulation (yes/no)

-

11

Aroused by torso stimulation (yes/no)

-

12

Aroused by touching (yes/no)

-

13

Aroused by kissing (yes/no)

-

14

Aroused by oral sex (yes/no)

-

15

What is the quality and reliability of your erection without assistive medication or devices? (lasts, doesn't last, soft)

-

16

What is the quality and reliability of your erection with assistive medication or devices? (lasts, doesn't last, soft, n/a)

-

17

What % most accurately describes your confidence you can rely, or be satisfied, with your erection? (25% or less, 50%, 75% or more)

-

18

Do you use any method of enhancing your erection? (yes/no)

-

19

Ever tried a device (yes/no)

-

20

Ever tried Viagra, Cialis, or Levitra (yes/no)

-

21

Have you tried to achieve ejaculation since your injury with various methods? (yes/no)

-

22

Have you ever achieved ejaculation since your injury? (yes/no)

-

23

Achieve ejaculation by hand stimulation (yes/no)

-

24

Achieve ejaculation by sexual intercourse (yes/no)

-

25

Achieve ejaculation by vibrator (yes/no)

-

26

Achieve ejaculation by oral stimulation (yes/no)

-

27

Achieve ejaculation by electroejaculation (yes/no)

-

28

Ejaculate for pleasure (yes/no)

-

29

Ejaculate for sexual intimacy (yes/no)

-

30

Ejaculate for spasm relief (yes/no)

-

31

Have you ever had the quality of your semen analyzed for fertility purposes? (yes/no)

-

32

Do you experience autonomic dysreflexia during sperm retrieval procedures? (yes, no, sometimes)

-

33

Have you fathered a biological child since your injury? (yes/no)

-

34

Have you ever experienced orgasm postinjury? (yes/no)

The resulting contingency tables were reviewed and factors accounting for <5% of the variability of responses (r2<0.05) were discarded. Factors accounting for >5% of the variability of responses are reported in the text along with the r2 value. In addition, χ2 analyses were performed for those factors and the P-values are reported in the text.

Results

The general demographics of the entire survey study population have been described in the accompanying manuscript.2 Table 1 provides a description specific to male participants (N=199).

General sexual activity and associated influences during sexual activity: male subpopulation

Further characterization of the male subpopulation of the study revealed that 90.5% had experienced a sexual relationship preinjury, 84.4% had experienced a sexual relationship postinjury, and only 55.3% were in a sexual relationship at the time of study participation. A total of 42.9% of the male subjects reported having genital sensation. Additionally, the majority of subjects reported that (1) they were not concerned about bladder (68.3%) or bowel (79.4%) incontinence during sexual activity and (2) bladder or bowel issues did not prevent them from seeking sexual activity (69.3%). Roughly one-third (28.6%) of all male subjects reported experiencing AD symptoms during sexual activity, but only 16.1% indicated that AD interfered with sexual activity and only 6% found AD symptoms during sexual activity to be pleasurable or arousing. Of the subjects who experienced AD during any type of sexual activity (57 of the 199, 28.6% of total), 91.2% had injuries at or above T6, 7% had injuries between T7 and T12, and 1.8% had lumbosacral injuries (r2=0.09 (r=0.30); χ2=18.67, P<0.0001).

Similar to the findings reported for the entire study population, the most commonly reported physical conditions experienced by men engaged in sexual activity were spasms (33.7%) and tingling sensations (32.7%). Many men, however, did not report experiencing any physical conditions during sexual activity (42.2%) or only reported experiencing one condition (31.2%). The primary reason for pursuing sexual activity was intimacy need (52.8%), followed by sexual need (22.6%), self-esteem (12.6%), to keep a partner (6%), other various reasons (5%), and fertility (1%). Additionally, by far the majority of the male participants stated that their SCI had altered their sexual sense of self (86.9%) and that improving sexual function would improve their quality of life (85.9%).

Sexual arousal and stimulation: adaptation

Several questions were asked in order to better determine how SCI impacts arousal in men. In this survey, arousal was not assigned a specific definition. Rather, it was left to the interpretation of each subject and his perception of arousal. Different questions were asked regarding physical and psychological aspects of arousal and stimulation leading to arousal.

Almost half of the subjects (45.2%) stated that their psychological feelings of arousal translated to their genitals as physical sensation (of which 55.5% could feel touch in the anal area). However, 19.1% were undecided regarding this phenomenon and 35.7% disagreed (of which 74.6% could not feel touch in the anal area). Therefore, arousal translated (ie referred) to the genitalia was positively correlated with having genital sensation (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=27.29, P<0.0001).

The majority of men reported the ability to feel a build up of sexual tension in their head during sexual stimulation (59.3%), but slightly fewer could feel a build up of sexual tension in their body during sexual stimulation (51.8%). Individuals that reported having genital sensation were more likely to report the ability to feel the build up of sexual tension in their bodies (r2=0.05 (r=0.22); χ2=14.19, P=0.0002). Additionally, roughly half reported not having any difficulty with becoming psychologically aroused (48.7%), yet the vast majority reported difficulty with becoming physically aroused (84.9%). There was a positive relationship between those individuals who reported having spasticity and who also reported having difficulty becoming physically aroused (r2=0.09 (r=0.30); χ2=11.07, P=0.0009).

Another set of questions were used to further characterize what types, and locations, of sexual stimulation were most arousing. A total of 39.7% of the subjects reported being aroused by sensual light stroking of nearby non-genital skin (such as inner thigh, perineum). This was positively correlated with the ability to feel touch in the anal area (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=17.44, P<0.0001) and the presence of genital sensation (r2=0.13 (r=0.36); χ2=33.92, P<0.0001).

Some individuals developed new areas of arousal AT their level of lesion (27.6%), but many more developed new areas of arousal ABOVE their level of lesion (41.7%). The development of new areas of arousal ABOVE the level of lesion was associated with multiple factors. Not surprisingly, there was a positive relationship with increasing time postinjury (r2=0.06 (r=0.25); χ2=14.42, P=0.0007). Interestingly, however, there was an inverse relationship with several other factors. Individuals who reported not being able to feel touch in the anal area were more likely to report developing new areas of arousal ABOVE their lesion level (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=17.64, P<0.0001). The same was found for individuals who reported not being able to lift their legs against gravity (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=16.32, P<0.0001) and not having genital sensation (r2=0.06 (r=0.25); χ2=15.92, P<0.0001). Conversely, individuals who reported having voluntary control of their bowels (r2=0.05 (r=0.22); χ2=12.97, P=0.0114) or who reported having chronic pain (r2=0.06 (r=0.25); χ2=14.19, P=0.0002) were much more likely to not develop new areas of arousal above their lesion level (78.26 and 78.33%, respectively).

Subjects were asked to describe the nature and location of the specific sexual stimulation that led to the best arousal for them (Figure 1). The most commonly reported type of sexual stimulation was touching the genitalia (35.2%). This was followed by stimulating the head/neck area and torso/arm/shoulder area (14.6% each). Other types of arousing stimulation were touching (11.1%) and kissing (7.5%) in general, visualization (5.5%), and oral sex (6%).

Erections: reliability and enhancement

After arousal changes, the next logical topic was erectile dysfunction. Figure 2 demonstrates that without using medication or assistive devices most men experienced erections, but that they were not reliable and did not last (61.8%). These were subclassified as not lasting but ‘very firm’ (17.1%), ‘firm’ (21.6%), and ‘not firm’ (23.1%). Only 13.1% had erections that did last (ie had a long duration). There was a relationship between the quality of erections without assistive medications or devices and the presence of spasticity during sexual activity (r2=0.08 (r=0.28); χ2=23.04, P<0.0001). A similar relationship and pattern was found for subjects who had genital sensation (r2=0.09 (r=0.30); χ2=31.56, P<0.0001). Table 2 details the percentage of subjects with/without spasticity during sexual activity and with/without genital sensation and the proportions having soft/no erections, non-lasting, or lasting erections.

Figure 3 depicts the quality and reliability of erections with the use of medication or devices. Compared to the data without assistance, there was a shift toward more subjects reporting experiencing erections that lasted (37.1%). When asked about the confidence on which they could rely on or be satisfied with their erections, 48.2% reported ⩽25% of the time and 38.6% reported 75% or more of the time. Those individuals who reported having genital sensation were more likely to report being confident 75% or more of the time on the reliability of their erections (52.0%; r2=0.06 (r=0.25); χ2=21.50, P<0.0001) than those individuals who did not have genital sensation. Neither the level of injury (above T6, between T7 and T12, or lumbosacral) nor experiencing AD during any type of sexual activity had any significant influence on the reliability of erections.

There are several methods available to men with SCI to attempt erection enhancement. There were 59.8% of the subjects who reported having previously tried some type of erection enhancing drug or device. Of those subjects, 22.1% had tried one method, 18.6% had tried two methods, and 19.1% had tried three or more methods. Figure 4 indicates the different types of methods that had been tried. Viagra was the most commonly tried medication (49.2%). Penile rings were the most commonly tried device (20.1%). At the time of participation in the study, the erection enhancing methods currently used by subjects were: nothing (23.1%), Viagra (20.6%), penile injections (7.5%), Cialis (5.5%), penile ring at base (3.5%), vacuum device (3%), Levitra (2.5%), penile prosthesis (1.5%), and other (1%). Some people (12.6%) were using a combination of methods. The most commonly reported side effects of erection enhancement were facial flushing (20.6%), headache (16.6%), lightheadedness (16.6%), and stuffy nose (10.6%), which were likely side effects of medications, and penile bruising (10.1%), which was likely due to devices or injections (Figure 5).

Ejaculation, fertility, and orgasm

The next group of questions was in regard to ejaculation. Approximately 80% of the subjects reported having tried to achieve ejaculation postinjury. However, only 47.7% reported ever having successfully achieved ejaculation postinjury. Note, when taking the survey, any subjects who reported not having achieved ejaculation postinjury were then routed to the next section of questions. For the remainder of the questions regarding ejaculation, thus, those individuals who had not successfully achieved ejaculation postinjury are represented as ‘n/a’ (not applicable). There were several factors associated with successful ejaculation. Not surprisingly, 81.3% of individuals who reported empting their bladders by controlled voiding also reported having achieved ejaculation postinjury (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=17.22, P=0.0085). Likewise, 86.9% of individuals who had voluntary control of their bowels were able to successfully ejaculate (r2=0.07 (r=0.26); χ2=17.93, P=0.0013). Additionally, 65.7% of subjects who reported having spasticity during sexual activity also reported having achieved ejaculation postinjury (r2=0.05 (r=0.22); χ2=13.02, P=0.0003). There was a trend for some individuals who reported experiencing autonomic dysreflexia during any type of sexual activity to also report having achieved ejaculation postinjury. However, this was a very weak relationship (r2=0.03, r=0.17) and was not significant. There was a similar trend and weak relationship for individuals with genital sensation (r2=0.04, r=0.20). There was also a trend for injury level to influence successful ejaculation. Of the subjects who have achieved ejaculation postinjury (95 of the 199, 47.7% of total), 74.7% had injuries at or above T6, 16.9% had injuries between T7 and T12, and 8.4% had lumbosacral injuries (r2=0.03, r=0.17). There was no significant relationship between the ability to feel touch in the anal area or the ability to voluntarily tighten the anal sphincter and having achieved ejaculation postinjury.

Figure 6 demonstrates that multiple methods have been used to achieve ejaculation. The top three most commonly used were hand stimulation (25.6%), sexual intercourse (20.6%), and vibrostimulation (14.1%). For each of the different methods tried, roughly two-thirds of the subjects were currently involved in a sexual relationship and one-third was not involved. There were 22.6% of the subjects who reported only using one method to achieve ejaculation, 14.6% who reported using two methods, and 9% who reported using three or more methods. The most commonly cited reasons for trying to ejaculate were for pleasure (30.7%) and for sexual intimacy (29.6%). As depicted in Figure 7, other reasons for trying to ejaculate were curiosity, general health, spasm relief, and fertility. There was no correlation between reporting having spasms or using spasticity medication and ejaculating for spasm relief in this study population.

Very few of the participants reported having had the quality of their semen analyzed for fertility purposes (14.1%). When asked about the occurrence of autonomic dysreflexia (AD) during sperm retrieval procedures, 12% of the subjects reported ‘yes’ or ‘sometimes’. However, it is important to note that just because 47.7% of the men reported the ability to achieve ejaculation postinjury it does not mean that they all underwent sperm retrieval procedures. Additionally, only 8% of all the subjects had fathered a biological child postinjury.

A total of 40.7% of the respondents reported experiencing orgasm postinjury. This, too, was associated with multiple factors. The length of time postinjury was positively correlated with having experienced orgasm (r2=0.08 (r=0.28); χ2=21.59, P<0.0001). Of the men who reported having experienced orgasm, 74.1% were greater than 10 years postinjury. There was a stronger correlation between having genital sensation and experiencing orgasm (r2=0.12 (r=0.35); χ2=30.42, P<0.0001). Of the men who reported having experienced orgasm, 72.8% had genital sensation. There was also a strong correlation between the reliability of erections and experiencing orgasm (r2=0.11 (r=0.33); χ2=28.23, P<0.0001). Of the men who reported having experienced orgasm, 58% were 75% or more confident in the reliability of their erections. The strongest correlation, by far, was the ability to achieve ejaculation (r2=0.38 (r=0.62); χ2=92.72, P<0.0001). Of the men who reported having experienced orgasm, 88.9% could achieve ejaculation. An in-depth analysis of orgasm in the men and women who participated in the survey will be presented in a subsequent manuscript.

Conclusions

Here, we have presented the data from the male portion of the survey questionnaire for which the general results were presented in an accompanying manuscript.2 The findings of the male-specific questions revealed that a significant amount of adaptation occurs regarding sexual stimulation and arousal in men living with ‘complete’ SCI. There was an inverse relationship between developing new areas of sexual arousal above the level of lesion and not having genital sensation, anal sensation, or the ability to lift legs against gravity. The most commonly reported sexual stimulation leading to the best arousal involved touching the genitalia, followed by stimulation of the head/neck and torso areas. Relative to erection and ejaculation, there was a positive relationship between reporting the occurrence of spasticity during sexual activity and erectile ability. Most reported erections did not last (ie short duration), however, and were unreliable without some type of erectile enhancement. Roughly 60% of the subjects had tried some type of erection enhancing drug or device, the most common being Viagra and penile rings, respectively. Only 48% had successfully achieved ejaculation postinjury and the most commonly used methods were hand stimulation, sexual intercourse, and PVS. The most commonly cited reasons for trying to ejaculate were for pleasure and for sexual intimacy, the least common reason being fertility. A total of 41% of subjects reported having experienced orgasm postinjury and this was influenced by the length of time postinjury, presence of genital sensation, reliability of erections, and ability to successfully ejaculate.

Potentially confounding variables

As described in detail in the accompanying manuscript,2 the demographics of the responded population are similar to the general SCI population demographics described for the Model SCI Systems. In summary, the majority of respondents were males, the primary cause of injury was vehicular crashes, and roughly half of the respondents had cervical injuries. The mean age at injury for the males was 28.3 years, which is lower than the 2005 reported mean age at injury of 37.6 years.31 However, it is important to note that the mean number of years post-injury for the males in this study was 14.2 and the younger age at injury is reflective of statistics reported from the Model SCI Systems prior to 2000.32 The proportion of sexually active individuals in the general SCI population is not known, to the best of the authors' knowledge, thus it is not known whether there was any bias toward the study respondents being more sexually active or sexually successful than the general SCI population.

The percentage of male respondents who reported experiencing continuous chronic pain and/or depression was 33 and 23%, respectively. The definition of chronic pain was not limited to neuropathic pain and depression was not limited to clinically diagnosed major depressive disorder. Although the incidence of pain associated with SCI is variable depending on the population and type of pain, it is estimate that roughly 65% of people living with SCI experience some degree of pain and that approximately one-third of that 65% rate their pain as severe.33 According to the 2005 Model SCI Systems statistical report,31 the percentage of people having major depressive disorder or other depressive symptoms ranges from 26 to 15% between 2 and 15 years postinjury, respectively. These estimates suggest that the incidence of continuous chronic pain and/or depression reported by our male study population is similar to that reported in the general SCI population. In that regard, it should be acknowledged that pain and depression are separate risk factors that can negatively impact sexual function separate from SCI.34, 35 It is possible that people who experience severe pain or depression which negatively impacts their participation in sexual activities may also have chosen not to participate in this survey.

Chronic SCI yields adaptive sexual stimulation and arousal in men with ‘complete’ injuries: underlying neuroplasticity

In the population of men who participated in this survey, it appears that subjects with self-described ASIA A injuries (ie no sensation in the anal or genital areas and no motor function below the lesion level) are more likely to develop, over time, new areas above the level of injury that, when stimulated, are sexually arousing. This is evident from multiple inverse relationships. Individuals who could not feel touch in the anal area were more likely to develop new areas of arousal above their injury level. The same relationship was found in subjects who did not have genital sensation and in subjects who could not lift their legs against gravity. This is suggestive of two phenomena. One, when sensation and movement originating in the lower cord are lost, individuals become more psychologically adaptive or open to trying nontraditional sexual stimulation. Two, neuroplasticity occurs in the spinal cord and ascending sensory pathways with time postinjury, which leads to normally non-sexually arousing areas (ie torso, shoulders) becoming arousing when stimulated under sexual circumstances.

Predictors of male sexual function

There appear to be several predictors of different aspects of male sexual function, at least in the population that responded to the survey. The most wide-ranging factor is the presence or absence of genital sensation (the genitals are innervated by the S2/3 dermatomes). When genital sensation is present, there is an increase in the likelihood of experiencing the following components of sexual function: (1) having psychological feelings of arousal translate to the genitals as a physical sensation, (2) feeling the build up of sexual tension in the body, (3) being aroused by sensual light stroking of nearby nongenital skin, (4) being confident ⩾75% of the time with reliability of erections, and (5) experiencing orgasm. Having genital sensation also decreases the likelihood of having soft/no erections when not using any methods of erectile enhancement.

Even more interesting, however, is that when genital sensation is absent, individuals are more likely to develop new areas of arousal above their level of lesion. The same adaptivity occurs in individuals who cannot feel touch in the anal area (innervated by the S4/5 dermatomes) and who cannot lift their legs against gravity. Several factors were found to be associated with the adaptation of arousal and it appears to be dependent upon sacral innervation. When the ability to feel touch in the anal area is present, individuals are more likely to be aroused by sensual light stroking of nearby non-genital skin. When subjects have voluntary control of their bowels, they are less likely to develop new areas of arousal above the level of lesion. Thus, when anal sensation and/or motor function are present or when genital sensation is present, individuals are more likely to be aroused by the ‘normal’ sexual stimulation (ie genital stimulation or nearby non-genital stimulation). When these sensations are lost, however, adaptation occurs and ‘new’ areas of sexual stimulation leading to arousal are developed (ie areas above the injury level, where sensation is intact). A greater length of time postinjury also influences the development of new areas leading to arousal. This adaptation could be due to multiple factors, including, but not limited to, (1) neuroplasticity, (2) increased openness to sexual experimentation, and/or (3) greater comfort in one's own sexuality. Relative to neuroplasticity, electrophysiological evidence for the reorganization of sensory pathways from the penis and anus following long-term spinal injury has been documented in male rats. When recording from a subset of medial thalamic and medullary somatovisceral convergent neurons (normally responsive to stimulation of the penis, anus, and ear/face) after removal of the lumbosacral inputs by ASIA A degree mid-thoracic chronic injury, the neuronal response to skin areas above the level of lesion (face, ear, upper torso) becomes enhanced with lower tactile thresholds.36, 37, 38 This is presumably caused by the removal of below the lesion inputs (genitalia, anus) and the subsequent strengthening of the remaining uninjured inputs (torso, face). This has never been observed in animals with acute injuries (4 h to 2 days) suggesting that the observed neuroplasticity requires time to develop.

The presence of spasticity also appears to be an important factor. When spasticity is present in the typical daily routine, individuals appear to have more difficulty becoming physically aroused when trying to be sexual. This could simply be due to interference of spasms when trying to perform sexual stimulation. When spasticity is present during sexual activity, however, there is a decrease in the likelihood of having soft/no erections when not using erectile enhancing drugs or devices. This does not necessarily indicate that spasms are inducing reflex erections. Rather, it is more likely an indicator of the intact sacral reflex arc. Finally, the presence of spasticity during sexual activity increases the likelihood of achieving ejaculation. The ability to successfully ejaculate post-SCI is also more likely to occur when voluntary control over the bowels and/or bladder is maintained. This suggests that there is some sparing of the descending bulbospinal pathways controlling the coordinated contraction of the urethral/anal sphincters and the perineal muscles which are involved in ejaculation.6 It is known that, in some men with SCI, ejaculation can reduce spasticity for a certain amount of time afterwards.28, 29 In our study population, however, spasm relief was not a commonly cited reason for ejaculating. It is quite possible that many men out in the general SCI community do not know about this phenomenon or about different devices available to assist with inducing ejaculation.

The likelihood of experiencing orgasm post-SCI is influenced by the following factors, in our study population: (1) greater length of time postinjury, (2) having genital sensation, (3) having reliable erections ⩾75% of the time, and (4) achieving ejaculation. As mentioned previously, a more detailed analysis of orgasm in our study population will be presented and discussed in a forthcoming manuscript.

Summary

The findings presented here indicate that SCI not only impairs male erectile function and ejaculatory ability, but also alters sexual arousal in a manner suggestive of neuroplasticity. Additionally, the majority of men pursue sexual activity for pleasure rather than merely reproduction. Clearly, more basic science and clinical research needs to be pursued in a manner not restricted to fertility, but encompassing all aspects of sexual arousal, function, and satisfaction.

References

Anderson KD . Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord injured population. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 1371–1383.

Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL . The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 328–337 (this issue).

Biering-Sørensen F, Sønksen J . Sexual function in spinal cord lesioned men. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 455–470.

Brown DJ, Hill ST, Baker HW . Male fertility and sexual function after spinal cord injury. In: Weaver LC, Polosa C (eds). Autonomic Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury. Elsevier: Amsterdam 2006, pp 427–439.

Elliott SL . Problems of sexual function after spinal cord injury. In: Weaver LC, Polosa C (eds). Autonomic Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury. Elsevier: Amsterdam 2006, pp 387–399.

Johnson RD . Descending pathways modulating the spinal circuitry for ejaculation: effects of chronic spinal cord injury. In: Weaver LC, Polosa C (eds). Autonomic Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury. Elsevier: Amsterdam 2006, pp 415–426.

Ramos AS, Samsó JV . Specific aspects of erectile dysfunction in spinal cord injury. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: S42–S45.

Hultling C, Giuliano F, Quirk F, Peña B, Mishra A, Smith MD . Quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury receiving VIAGRA® (sildenafil citrate) for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 363–370.

Sánchez Ramos A et al. Efficacy, safety and predictive factors of therapeutic success with sildenafil for erectile dysfunction in patients with different spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 636–643.

Derry F, Hultling C, Seftel AD, Sipski ML . Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate (Viagra®) in men with erectile dysfunction and spinal cord injury: a review. Urology 2002; 60 (Suppl 2B): 49–57.

Del Popolo G, Li Marzi V, Mondaini N, Lombardi G . Time/duration effectiveness of sildenafil versus tadalafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in male spinal cord-injured patients. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 643–648.

Mittmann N et al. Erectile dysfunction in spinal cord injury: a cost-utility analysis. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 358–364.

Garcia-Bravo AM et al. Determination of changes in blood pressure during administration of sildenafil (Viagra®) in patients with spinal cord injury and erectile dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 301–308.

DeForge D et al. Male erectile dysfunction following spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 1–9.

Denys P, Mane M, Azouvi P, Chartier-Kastler E, Thiebaut JB, Bussel B . Side effects of chronic intrathecal Baclofen on erection and ejaculation in patients with spinal cord lesions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 494–496.

Bird VG, Brackett NL, Lynne CM, Aballa TC, Ferrell SM . Reflexes and somatic responses as predictors of ejaculation by penile vibratory stimulation in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 514–519.

Courtois F, Geoffrion R, Landry E, Bélanger M . H-Reflex and physiologic measures of ejaculation in men with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 910–918.

Sønksen J, Ohl DA . Penile vibratory stimulation and electroejaculation in the treatment of ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Androl 2002; 25: 324–332.

Trabulsi EJ, Shupp-Byrne D, Sedor J, Hirsch IH . Leukocyte subtypes in electroejaculates of spinal cord injured men. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83: 31–34.

Randall JM, Evans DH, Bird VG, Aballa TC, Lynne CM, Brackett NL . Leukocytospermia in spinal cord injured patients is not related to histological inflammatory changes in the prostate. J Urol 2003; 170: 897–900.

Basu S, Aballa TC, Ferrell SM, Lynne CM, Brackett NL . Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are elevated in seminal plasma of men with spinal cord injuries. J Androl 2004; 25: 250–254.

Cohen DR, Basu S, Randall JM, Aballa TC, Lynne CM, Brackett NL . Sperm motility in men with spinal cord injuries is enhanced by inactivating cytokines in the seminal plasma. J Androl 2004; 25: 922–925.

Sønksen J, Ohl DA, Giwercman A, Biering-Sørensen F, Skakkebæk NE, Kristensen JK . Effect of repeated ejaculation on semen quality in spinal cord injured men. J Urol 1999; 161: 1163–1165.

Hamid R, Patki P, Bywater H, Shah PJR, Craggs MD . Effects of repeated ejaculations on semen characteristics following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 369–373.

Sheel AW, Krassioukov AV, Inglis JT, Elliott SL . Autonomic dysreflexia during sperm retrieval in spinal cord injury: influence of lesion level and sildenafil citrate. J Appl Physiol 2005; 99: 53–58.

Elliott SL, Krassioukov AV . Malignant autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injured men. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 386–392.

Elliott SL, McBride K, Ekland M, Krassioukov A . Characteristics of autonomic dysreflexia in men with SCI undergoing 296 procedures of vibrostimulation for sperm retrieval. J Spinal Cord Med 2005; 28: abstract #52, p149, ASIA 31st Annual Meeting.

Læssøe L, Nielsen JB, Biering-Sørensen F, Sønksen J . Antispastic effect of penile vibration in men with spinal cord lesion. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 919–924.

Alaca R, Goktepe AS, Yildiz N, Yilmaz B, Gunduz S . Effect of penile vibratory stimulation on spasticity in men with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 84: 875–879.

Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL . Spinal cord injury influences psychogenic as well as physical components of female sexual ability. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 349–359 (this issue).

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Annual report for the model spinal cord injury care systems. University of Alabama: Birmingham, AL 2005.

Nobunaga AI, Go BK, Karunas RB . Recent demographic and injury trends in people served by the Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1372–1382.

Siddall PJ, Loeser JD . Pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 63–73.

Harrison J, Glass CA, Owens RG, Soni BM . Factors associated with sexual functioning in women following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 687–692.

Kwan KS, Roberts LJ, Swalm DM . Sexual dysfunction and chronic pain: the role of psychological variables and the impact on quality of life. Eur J Pain 2005; 9: 643–652.

Hubscher CH, Johnson RD . Effects of acute and chronic mid-thoracic spinal cord lesions on the neural circuitry mediating male sexual function – I. Ascending pathways. J Neurophysiol 1999; 82: 1381–1389.

Johnson RD, Hubscher CH . Plasticity in supraspinal viscerosomatic convergent neurons following chronic spinal cord injury. In: Burchiel K, Yezierski R (eds). Spinal Cord Injury Pain: Assessment, Mechanisms, Management. IASP Press: Seattle 2002, pp 205–217.

Hubscher CH, Johnson RD . Chronic spinal cord injury-induced changes in the response of thalamic neurons. Exp Neurol 2006; 197: 177–188.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dave Pataky for technical assistance related to setting up the survey software and website. Additionally, we thank the Vancouver-based GF Strong Sexual Health Rehabilitation team for their input in the development of the questionnaire. Above all else, sincere gratitude is expressed to the community living with spinal cord injury for their continued willingness to provide input about important and real issues related to SCI to better enable researchers to ask and answer clinically relevant questions through experimental means.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, K., Borisoff, J., Johnson, R. et al. Long-term effects of spinal cord injury on sexual function in men: implications for neuroplasticity. Spinal Cord 45, 338–348 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101978

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101978

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Orgasm and SCI: what do we know?

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Fertility and sexuality in the spinal cord injury patient

World Journal of Urology (2018)

-

Evaluation of sexual and fertility dysfunction in spinal cord-injured men in Jamaica

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)

-

The relationship between anxiety, depression and religious coping strategies and erectile dysfunction in Iranian patients with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

Development of a comprehensive survey of sexuality issues including a self-report version of the International Spinal Cord Injury sexual function basic data sets

Spinal Cord (2016)