Abstract

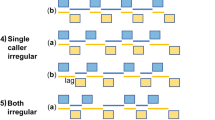

HARTSHORNE1,2 has proposed that a direct relationship exists between the degree of continuity and versatility in bird song. In other words, the more continuously a bird species sings (that is, the longer the song lengths relative to pauses between songs), the higher is the probability that successive songs will be different. Birds of a given species may sing with immediate variety, where successive songs are different, whereas other species tend to sing with eventual variety, where a song type is repeated many times before another is introduced; males of some species have only a single song type, and thus show a lack of variety in their singing. Hartshorne proposed that a monotony threshold exists, making singing behaviours with high continuity and low versatility too monotonous and therefore ineffective. Because Hartshorne collected information primarily by ear, his data on singing behaviours were not always accurate3; also, his philosophical approach to the aesthetics of bird song remains incompatible with the more rigorous approaches used by most biologists. His hypothesis has been further discredited by a report4 which, through quantitative analyses of data compiled for 39 species, found no significant correlation (rs = 0.20) between versatility and continuity of singing. However, because Dobson and Lemon4 used repertoire size as the measure of versatility, Hartshorne's monotony–threshold hypothesis was not actually tested, for his1,2 measure of versatility involved the sequential organisation of different songs during a singing session, not merely the total repertoire size. This is an important distinction, as Hartshorn5,23 stresses, for a species such as the Carolina wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus) may have a large repertoire size but sing a song type 100 times before changing to another. Hartshorne considers such song patterning to be non-versatile5,23, whereas Dobson and Lemon rank this species as highly versatile. The purpose of this report, then, is threefold. First, because of these differences in the definition of versatility, I test Hartshorne's monotony–threshold hypothesis, using the original and some revised (see Table 1) data tabulated by Dobson and Lemon4. Second, I discuss the difficulties involved in measuring continuity and versatility among species with very different singing behaviours. Finally, I review data from wrens (Troglodytidae) which reveal a clear relationship between several different and, I feel, improved measures of continuity and versatility.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hartshorne, C. Auk 73, 176–192 (1956).

Hartshorne, C. Born to Sing (Indiana University Press, Ploomington, 1973).

Verner, J. The Living Bird 14, 263–300 (1975).

Dobson, C. W. & Lemon, R. E. Nature 257, 126–128 (1975).

Hartshorne, C. Auk 73, 177 (1956).

Kroodsma, D. E. Am. Nat. 11, 995–1008 (1977).

Kroodsma, D. E. Condor 77, 294–303 (1975).

Kroodsma, D. E. & Verner, J. The Auk (in the press).

Petrinovich, L. & Peeke, H. V. S. Behav. Biol. 8, 743–748 (1973).

Krebs, J. R. Anim. Behav. 25, 475–478 (1977).

Howard, R. D. Evolution 28, 428–438 (1974).

Kroodsma, D. E. Science 192, 574–575 (1976).

Nottebohm, F. Am. Nat. 106, 116–140 (1972).

Reynard, G. B. Living Bird 2, 139–148 (1963).

Stein, R. C. Auk 73, 507–512 (1956).

Borror, D. J. Ohio J. Sci. 64, 195–207 (1964).

Kroodsma, D. E. Z. Tierpsychol. 35, 352–380 (1974).

Fish, W. R. Condor 55, 250–257 (1953).

Marler, P. & Isaac, D. Condor 62, 272–283 (1960).

Marler, P. & Isaac, D. Auk 77, 433–444 (1960).

Mulligan, J. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 81, 1–76 (1966).

Mulligan, J. A. Proc. 12th int. Orn. Congr. 272–284 (1963).

Hartshorne, C. Born to Sing, 120 (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1973).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

KROODSMA, D. Continuity and versatility in bird song: support for the monotony–threshold hypothesis. Nature 274, 681–683 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1038/274681a0

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/274681a0

This article is cited by

-

Sexual display complexity varies non-linearly with age and predicts breeding status in greater flamingos

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Vocal mimicry in AfricanCossypha robin chats

Journal für Ornithologie (2002)

-

Temporal patterning of within-song type and between-song type variation in song repertoires

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (1994)

-

Temporal patterning of within-song type and between-song type variation in song repertoires

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (1994)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.