Abstract

The development of drug addiction involves a transition from recreational use to compulsive drug seeking and taking, and this progression can occur rapidly with cocaine use. These data highlight the importance of early drug exposure and the development of drug dependence; however, little experimental attention has been paid to this phenomenon in animal models of drug abuse. The present experiments demonstrate a progressive and rapid sensitization to the reinforcing strength of cocaine assessed using a progressive ratio (PR) schedule in rats. The first experiment found that rats show increased breakpoints over a 2-week period following acquisition. Subsequent experiments examined the role of total cocaine intake during the initial exposure period and found that low intakes (20 mg/kg/day × 5 days) resulted in sensitization, whereas relatively higher intake (60 or 100 mg/kg/day × 5 days) suppressed the development of sensitization. In contrast, this higher level of intake (60 mg/kg/day × 5 days) only transiently suppressed the expression of sensitization. Examination of breakpoints maintained by various doses of cocaine revealed an upward and leftward displacement of the cocaine dose–effect curve, relative to nonsensitized animals. These studies describe a form of sensitization that occurs rapidly to the reinforcing effects of cocaine, and provide a model to study the potential impact of initial experience on the development of drug dependence.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The process of drug addiction is typically described as a transition from recreational use to compulsive drug taking and seeking (Cami and Farre, 2003). Drug dependence is characterized by augmentation of drug intake, an increase in the time and energy spent on drug seeking and taking, difficulty in remaining abstinent, and drug use in the face of known adverse consequences (DSM IV, 2000; Gawin and Kleber, 1986; Mendelson and Mello, 1996).

Self-administration studies in rodents have provided models that reflect specific aspects of this addiction process. For example, animals show escalation of drug intake and/or binge-like patterns of self-administration when daily sessions are extended to 6 or more hours (Ahmed and Koob, 1998) or drug is available 24 h/day (Morgan and Roberts, 2004). Recent studies have shown that prolonged access to drug results in a persistence of drug seeking in the presence of an aversive conditioned stimulus and drug taking that is less sensitive to punishment (Deroche-Gamonet et al, 2004; Vanderschuren and Everitt, 2004). In addition, animals show progressively increasing levels of reinstatement following withdrawal (Grimm et al, 2001).

Another way to study the addiction process is to examine conditions in which sensitization to the behavioral effects of cocaine occurs. In particular, we have been interested in changes in the reinforcing strength of cocaine using progressive ratio (PR) schedules. PR schedules have been useful in documenting changes in the reinforcing strength of cocaine following various drug histories in self-administering animals (Richardson and Roberts, 1996; Stafford et al, 1998). It has been shown previously that cocaine-reinforced breakpoints on a PR schedule can increase or decrease (ie show sensitization or tolerance) following periods of high drug intake (Li et al, 1994; Morgan et al, 2002, 2005; Roberts et al, 2002). For example, prolonged daily access to cocaine on a discrete-trial (DT) schedule (which allows self-administration 24 h/day) in combination with an extended period of drug deprivation produces sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine (Morgan et al, 2002, 2005; Morgan and Roberts, 2004). All of the above animal models of the addiction process have used drug access conditions that promote high levels of drug intake over relatively prolonged periods of time.

Epidemiological evidence has shown that there is a rapid progression from initial or recreational use to drug dependence in some individuals (Wagner and Anthony, 2002; Ridenour et al, 2003). These studies highlight the fact that early drug experiences can have profound effects on the development of addiction-like behaviors, and suggest that more experimental attention be devoted to the influences of early drug exposure. Interestingly, while examining self-administration on a PR schedule in animals with very little cocaine experience, we found that breakpoints progressively increased over a 2-week period. That is, sensitization of cocaine-reinforced breakpoints was observed in animals with very limited exposure to drug. Here, we describe a systematic evaluation of this phenomenon. Additional studies were conducted to isolate the role of total drug intake on subsequent sensitization, its effects on the cocaine dose–response curve, and differential effects of high levels of intake on the development and expression of sensitization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Surgery

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, Ind., USA) weighing approximately 350 g upon arrival into the laboratory were used as subjects. Throughout the experiment, animals had food and water available ad libitum and were housed individually in cages under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights off at 1400 hours). After at least 3 days from arrival, each rat was anesthetized with an i.p. injection of a combination of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg) and implanted with a chronic indwelling Silastic cannula into the right jugular vein that exited through the skin on the dorsal surface in the region of the scapulae (Roberts and Goeders, 1989). All rats were administered butorphanol tartrate (0.2 mg/kg, s.c.), as a postsurgery analgesic, and penicillin (1 ml/kg; 300 000 units/ml, i.m.) to prevent infection immediately following the surgery. Catheters were flushed daily with a 2% heparin/2% penicillin solution for an additional 7 days to help prevent clotting and infections. After 7 days, animals were flushed daily with 2% heparin for the remainder of the experiment. Tygon tubing was attached at the back, enclosed by a stainless steel protective tether, and connected to a counterbalanced fluid swivel (Instech Laboratories, Inc., Plymouth Meetings, Pa., USA) mounted above the chamber. Tygon tubing connected the swivel to an infusion pump (Razel Scientific Instruments, Inc., Stamford, Conn., USA). Self-administration began at least 3 days after recovery from surgery.

Self-Administration Training Procedures

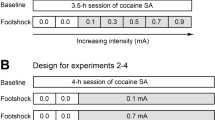

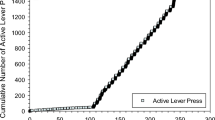

Following surgery, animals were housed in experimental chambers (30 × 30 × 30 cm). Experiments were conducted for 7 days/week and daily sessions started at 1400 hours. The start of a session was indicated by inserting a lever into the chamber. Cocaine (1.5 mg/kg/inj) was available on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement and was injected over approximately 4–5 s (depending on body weight). Following each response, the lever was retracted for a 20-s postresponse time-out period. Each training session lasted until 40 injections had been self-administered, at which time, the levers retracted until the start of the next session. Acquisition of cocaine self-administration was defined as drug-reinforced responding in a regular pattern, with approximately 10-min interresponse intervals during the last 20 injections in one test session (the range of average interresponse intervals across all rats was 7.25–14.05 min). Figure 1 shows an example event record. Animals that did not acquire self-administration within 10 days were excluded (approximately 10%). The animals used in this study acquired self-administration in 1–5 days; total cocaine intake during these sessions ranged from approximately 60 to 150 mg/kg. Following acquisition, animals were randomly placed into experimental groups, and these conditions are described in Table 1.

Cocaine self-administration induced increases in cocaine's reinforcing effects following limited exposure (ie 1 day of training; Group A). Data are expressed as the mean (±SEM) breakpoint and asterisks indicate significant differences from day 1 (F13, 195=7.6; p<0.0001). Horizontal lines represent breakpoints (±SEM) from the last eight published papers from this laboratory. The right panel shows an event record from experimental day 1 (FR schedule) and cumulative records from days 2, 7, and 15 (PR schedule) for a representative rat. Notice the progressive increase in breakpoint and the total number of responses emitted across days.

PR Schedule of Reinforcement

Following training, a PR schedule was introduced. Under these conditions, delivery of intravenous cocaine injections was contingent on an increasing number of responses incremented through the following progression: 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603 (Richardson and Roberts, 1996). Lever pressing was maintained by 1.5 mg/kg/inj cocaine on a PR schedule for at least 14 days. Breakpoints were defined as the final ratio values (ie the response requirement for the last obtained reinforcer). Sessions were conducted 24 h/day although breakpoints were reached within 6 h during nearly every session.

Experiment 1: Effects of Limited Initial Exposure

In order to limit cocaine exposure during training, the day after there was evidence of acquisition of cocaine self-administration, animals (Group A) were tested on a PR schedule for 2 weeks.

Experiment 2: Effects of Cocaine Intake during the Initial Exposure

The day following acquisition of the drug-reinforced response, animals were divided into three groups that received an additional 5 days of self-administration on an FR1 schedule (Groups B, C, and D). Rats self-administered either 13, 40, or 67 injections each day, resulting in daily cocaine intakes of 20, 60, or 100 mg/kg, respectively. Schedule conditions were then changed to a PR schedule of reinforcement for 2 weeks. Breakpoints on the PR schedule were obtained using 1.5 mg/kg/inj cocaine.

Experiment 3: Effects of High Drug Intake on the Expression of Sensitization

Following self-administration on a PR schedule for 14 days, animals with restricted initial exposure (60 mg/kg/day × 1 day; Group A) or more prolonged initial exposure (60 mg/kg/day × 5 days; Group C) were given access to 40 injections of 1.5 mg/kg/inj for additional 5 days (a total of 300 mg/kg cocaine). Breakpoints on the PR schedule maintained by cocaine were then assessed for 7 days.

Experiment 4: Determination of the Cocaine Dose–Response Curve

In animals that had restricted initial exposure to cocaine (ie 20 mg/kg/day × 5 days; Group B) and extensive initial exposure to cocaine (ie 100 mg/kg/day × 5 days; Group D), a cocaine dose–response curve was determined following 14 days of self-administration (1.5 mg/kg/inj) on the PR schedule. Breakpoints maintained by 0.19, 0.38, 0.75, and 3 mg/kg/inj cocaine were determined in a random order. Saline self-administration on a PR schedule was then examined. Average breakpoints were obtained from 3 days of stable responding (ie number of injections varied by less than three reinforcers).

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD, USA. Cocaine was dissolved in sterilized 0.9% saline and passed through a microfilter to make a concentration of 5 mg/ml cocaine (expressed at the salt weight). Responses resulted in the pumps being activated for 4–5 s, depending on the animal's body weight, to deliver approximately 0.1 ml solution, which corresponds to 1.5 mg/kg/inj. The effects of various cocaine doses were studied by altering the concentration of cocaine.

Data Analysis

The main dependent variable was breakpoint on a PR schedule. Data were analyzed using one- and two-way ANOVA with GB-stat software (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA) and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Newman–Keuls post hoc analyses were used to identify differences between groups and time effects. Analyses were conducted on data subjected to a logarithmic transformation to increase homogeneity of variance.

RESULTS

Limited Initial Exposure Results in Increases in the Reinforcing Strength of Cocaine

Breakpoints maintained by cocaine following acquisition (Group A) increased progressively and significantly over 14 days (Figure 1; F13, 194=7.6, p<0.01). Animals made approximately 268 responses for the last reinforcer (for a total of 1400 responses in the session) by the end of testing, compared to 50 responses for the final reinforcer (a total of 200 responses) during the first PR session. Horizontal dashed and solid lines in Figure 1 represent the average breakpoints (±1 SEM) from the last eight published papers from this laboratory using a PR schedule. The pattern of responding across days for an individual animal is also shown (Figure 1, right). Note that the group of animals with limited exposure to cocaine had breakpoints that were similar to average breakpoints from previous studies by the second PR session. This indicates that extensive training is not necessary in order to generate typical patterns of cocaine self-administration and cocaine-reinforced breakpoints. Importantly, breakpoints for the group continued to increase over a 14-day period.

Effects of Cocaine Intake during Initial Exposure on the Development of Sensitization

To examine the role of initial drug intake on the development of sensitization, three groups of animals were given different levels of cocaine exposure during 5 days of self-administration on an FR1 schedule. Separate groups self-administered 13, 40, or 67 injections of cocaine per day, resulting in daily intakes of approximately 20, 60, and 100 mg/kg cocaine (see Figure 2, left panel for representative event records). Only animals receiving the lowest initial drug intake (Group B) showed a progressive increase in breakpoints over the 14-day period (Group × Day interaction: F2, 224=55.9, p<0.01). Data from this group are similar to the results shown in Figure 1; these data replicate the initial finding and suggest that sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine can occur following 1 or 5 days of training provided that cocaine intake is restricted. Neither of the groups given access to higher levels of cocaine for 5 days during the initial exposure period (Groups C or D) showed a significant change in breakpoints. The group self-administering 40 injections per day represents our typical training conditions, and replicates our previous findings that these training parameters result in stable breakpoints (Morgan and Roberts, 2004).

Cocaine intake during initial exposure is critical to the development of sensitization. In the left panel, event records of representative animals that self-administered 13, 40, or 67 reinforcers per day during FR testing (daily intakes of 20, 60, or 100 mg/kg/day) are shown. Limited intake during initial access to cocaine (Group B) induced increases in breakpoints over time. Higher levels of cocaine during these 5 days (Groups C and D) prevented increases in breakpoint. Symbols represent the mean (±SEM) breakpoint. Asterisks indicate significant differences between Group B and the other two groups (p's<0.05). Filled circles: Group B; open circles: Group C; filled triangles: Group D.

Effects of High Intake on the Expression of Sensitization

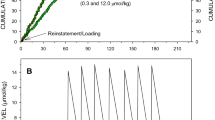

It appeared that exposure to higher levels of cocaine (60 or 100 mg/kg/day × 5 days; Group C or D) prevented the development of sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine. In order to test whether high cocaine intake would affect the expression (rather than the development) of this response, animals in Group A and C were permitted to self-administer 60 mg/kg/day cocaine over 5 days on an FR1 schedule. Breakpoints were determined for 7 days thereafter. In the group that had limited exposure during training (Group A), 5 days of cocaine self-administration on an FR1 schedule transiently decreased breakpoints (Figure 3), but breakpoints quickly returned to their previous levels. In contrast, the animals with lower baseline breakpoints were not changed following 5 days of FR1 self-administration. These data indicate that high levels of cocaine intake inhibited the development (Figure 2), but only transiently affected the expression of this sensitization (Figure 3).

High levels of cocaine intake only transiently alter the expression of sensitization. Group A had significantly higher breakpoints than Group C during baseline. The middle panel shows event records for two representative animals with self-administration of 60 mg/kg/day for 5 days on an FR1 schedule. Although this level of intake blocked the development of this sensitization (see Figure 2), there were only transient decreases in breakpoints in Group A. Cocaine self-administration on an FR1 schedule failed to alter breakpoints in Group C. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups (p<0.05). Filled circles: Group A; open circles: Group C.

Cocaine Dose–Response Curve Following Differential Exposure Conditions

Cocaine dose–response curves were obtained in animals receiving either limited (Group B) or extended (Group D) initial exposure to cocaine (Figure 4). Animals in Group B produced significantly higher breakpoints at doses of 0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg/inj cocaine, representing an upward/leftward shift of the dose–response curve. Similar breakpoints were obtained at lower doses of cocaine (0.19 and 0.38 mg/kg/inj) and saline across groups, suggesting that the increase in breakpoint was dependent on cocaine dose, and was not a consequence of nonspecific increases in lever-pressing.

Limited intake during initial exposure results in an upward/leftward shift of the dose–response curve. The dose–response curve for the group of animals with limited initial exposure to cocaine (Group B) was displaced upward and leftward relative to the dose–response curve in animals with higher levels of cocaine intake during training (Group D). No differences were observed with the lower doses of cocaine and saline. Data symbols represent the mean (±SEM) breakpoint. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present findings demonstrate sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine in self-administering animals that occurs during the early phase of a drug-taking history. The major findings are (1) animals with very limited exposure to cocaine show sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine as demonstrated by a PR schedule; (2) cocaine-reinforced breakpoints increase substantially over a 2-week period; (3) relatively high cocaine exposure abolishes the development, but not the expression of such sensitization; (4) this sensitization resulted in an upward and leftward shift in the dose–effect curve.

The present data appear to represent a fundamentally different phenomenon than has previously been reported. It will be argued here that the data suggest that there are at least two distinct stages involved in the addiction process. One, demonstrated here, illustrates that relatively low drug intake can sensitize the user to the reinforcing effects of the drug and a subsequent stage in which high drug intake produces a deteriorating behavioral profile.

The emphasis of a growing research effort has been on modeling aspects of DSM-IV criteria following periods of high drug intake. For example, experimental conditions that result in progressive increases in intake (Ahmed and Koob, 1998), high rates of relapse (Grimm et al, 2001), responding in the presence of adverse consequences (Deroche-Gamonet et al, 2004; Vanderschuren and Everitt, 2004), and increases in the ‘incentive-motivational’ effects of cocaine (Deroche et al, 1999; Deroche-Gamonet et al, 2004) have all been described. With respect to increases in cocaine-reinforced breakpoints, we have shown that round-the-clock access to cocaine for 10 days coupled with a 7-day deprivation period produces an upward shift in the cocaine dose–response curve (Liu et al, 2005). All of these changes require either extended periods of self-administration or very high levels of drug intake. These important demonstrations appear to model aspects of a late stage of the addiction process.

The early stages of the addiction process have received very little attention in the self-administration literature. The clinical evidence suggests that things can happen fast and early (Wagner and Anthony, 2002). Here, we demonstrate that animals exposed to relatively few drug injections (Groups A and B) showed a progressive increase in cocaine-reinforced breakpoints. After this initial change in cocaine-reinforced breakpoints, it was shown that the cocaine dose–effect curve was displaced to the left and upward relative to the group with higher initial exposure (Group D). Note that the robust shift in the cocaine dose–effect curve is roughly the same in magnitude previously reported following the (high intake) binge-abstinence procedure (Morgan et al, 2005). Although the eventual consequences were similar (increases in breakpoints), the experimental conditions producing these changes were very different. For example, the binge-abstinence effects on breakpoints depend on prolonged, high-intake access, and require a deprivation period. The findings described in this paper result from very limited cocaine exposure, they occur very quickly, and a deprivation period is not necessary. While many recent studies have focused on the later stages of addiction process, these findings suggest that important changes can happen early.

Sensitization to the incentive and motivational effects of cocaine has been suggested to be an underlying process of the development of drug addiction (Robinson and Berridge, 1993, 2003, 2004). Most research has studied this process using locomotor sensitization as a model (Kilbey and Ellinwood, 1977; Karler et al, 1989, 1990; Kalivas and Duffy, 1993a, 1993b; Vanderschuren et al, 1999), and a number of labs are now examining the link between psychostimulant-induced locomotor activation and self-administration. For example, self-administration of cocaine produces sensitization to the locomotor-activating effects (Hooks et al, 1994; Phillips and Di Ciano, 1996; Zapata et al, 2003; Ben-Shahar et al, 2004). It has also been demonstrated that rats receiving experimenter-administered stimulants, which produces a sensitized locomotor response, acquire self-administration faster and/or at lower doses (Horger et al, 1990, 1992; Schenk et al, 1991). Animals treated this way also respond to higher breakpoints when subsequently tested on a PR schedule (Mendrek et al, 1998; Lorrain et al, 2000; Covington and Miczek, 2001; Suto et al, 2002, 2003; Vezina et al, 2002). Taken together, there appear to be links between locomotor sensitization and sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine.

Interestingly, the present demonstration of sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine and sensitization of the locomotor-activating effects are behaviorally similar. Both happen rapidly and progressively (eg Vanderschuren et al, 1999), and are suppressed by relatively high doses of cocaine (present study, Dalia et al, 1998). Furthermore, Robinson and co-workers have demonstrated that the development of sensitization to the locomotor-activating effects of cocaine is influenced by the speed of intravenous injection (Samaha et al, 2002, 2004; Samaha and Robinson, 2005). Recently, we have demonstrated that the speed of injection also plays a role in the sensitization of cocaine-reinforced breakpoints (Liu et al, submitted). Given these similarities, we suggest that the behavioral processes may be related, although perhaps not identical.

Many have drawn a parallel between locomotor sensitization and dopamine responsivity (eg Akimoto et al, 1989, 1990; Kalivas and Duffy, 1993a, 1993b; Pierce and Kalivas, 1995; Pierce et al, 1996; Tanabe et al, 2004; Anderson and Pierce, 2005) and Vezina and co-workers (see review, Vezina, 2004) have clearly demonstrated that noncontingent stimulant administration that increases subsequent PR performance also increases dopaminergic responsivity (Vezina et al, 2002). However, changes in dopamine dynamics may not account for all changes in the reinforcing effects of cocaine. For example, Ahmed et al (2003) show no change in dopamine dynamics following high intake, and extended access to cocaine. Following discrete-trial cocaine self-administration (high intake, 24 h/day access) and deprivation, conditions that result in increased breakpoints (Morgan et al, 2005), animals appear to be hypodopaminergic and show a blunted dopamine response to cocaine administration (Mateo et al, 2005). Interestingly, in one report showing sensitization to the dopaminergic effects of cocaine as a consequence of self-administration (Bradberry, 2000), it was noted that only a small amount of drug exposure was required to produce progressive increases in the brain response to self-administered cocaine. It is unclear at this point, whether the sensitization observed in the present study is associated with greater or lower responsivity of the dopaminergic system.

Taken together, the present findings emphasize the need to study the process of the development of drug addiction from multiple angles. Here, we have an important demonstration of sensitization that occurs during the very early phases of drug use, and may represent a method to study the sometimes rapid transition from initial drug use to drug dependence and addiction. This model provides one more tool to evaluate environmental determinants and neurobiological correlates of the addiction process and may allow for the testing of pharmacological interventions designed to reduce drug use.

References

Ahmed SH, Koob GF (1998). Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science 282: 298–300.

Ahmed SH, Lin D, Koob GF, Parsons LH (2003). Escalation of cocaine self-administration does not depend on altered cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens dopamine levels. J Neurochem 86: 102–113.

Akimoto K, Hamamura T, Kazahaya Y, Akiyama K, Otsuki S (1990). Enhanced extracellular dopamine level may be the fundamental neuropharmacological basis of cross-behavioral sensitization between methamphetamine and cocaine—an in vivo dialysis study in freely moving rats. Brain Res 507: 344–346.

Akimoto K, Hamamura T, Otsuki S (1989). Subchronic cocaine treatment enhances cocaine-induced dopamine efflux, studied by in vivo intracerebral dialysis. Brain Res 490: 339–344.

Anderson SM, Pierce RC (2005). Cocaine-induced alteration in dopamine receptor signaling: implication for reinforcement and reinstatement. Pharmacol Therap. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.12.004.

Ben-Shahar O, Ahmed SH, Koob GF, Ettenberg A (2004). The transition from controlled to compulsive drug use is associated with a loss of sensitization. Brain Res 995: 46–54.

Bradberry CW (2000). Acute and chronic dopamine dynamics in a nonhuman primate model of recreational cocaine use. J Neurosci 20: 7109–7115.

Cami J, Farre M (2003). Drug addiction. N Engl J Med 349: 975–986.

Covington III HE, Miczek KA (2001). Repeated social-defeat stress, cocaine or morphine. Effects on behavioral sensitization and intravenous cocaine self-administration ‘binges’. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 158: 388–398.

Dalia AD, Norman MK, Tabet MR, Schlueter KT, Tsibulsky VL, Norman AB (1998). Transient amelioration of the sensitization of cocaine-induced behaviors in rats by the induction of tolerance. Brain Res 797: 29–34.

Deroche V, Le Moal M, Piazza PV (1999). Cocaine self-administration increases the incentive motivational properties of the drug in rats. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2731–2736.

Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV (2004). Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science 305: 1014–1017.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2000). 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

Gawin FH, Kleber HD (1986). Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43: 107–113.

Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y (2001). Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 412: 141–142.

Hooks MS, Duffy P, Striplin C, Kalivas PW (1994). Behavioral and neurochemical sensitization following cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 115: 265–272.

Horger BA, Giles MK, Schenk S (1992). Preexposure to amphetamine and nicotine predisposes rats to self-administer a low dose of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 107: 271–276.

Horger BA, Shelton K, Schenk S (1990). Preexposure sensitizes rats to the rewarding effects of cocaine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 37: 707–711.

Kalivas PW, Duffy P (1993a). Time course of extracellular dopamine and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. I. Dopamine axon terminals. J Neurosci 13: 266–275.

Kalivas PW, Duffy P (1993b). Time course of extracellular dopamine and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. II. Dopamine perikarya. J Neurosci 13: 276–284.

Karler R, Calder LD, Chaudhry IA, Turkanis SA (1989). Blockade of ‘reverse tolerance’ to cocaine and amphetamine by MK-801. Life Sci 45: 599–606.

Karler R, Chaudhry IA, Calder LD, Turkanis SA (1990). Amphetamine behavioral sensitization and the excitatory amino acids. Brain Res 537: 76–82.

Kilbey MM, Ellinwood Jr EH (1977). Reverse tolerance to stimulant-induced abnormal behavior. Life Sci 20: 1063–1075.

Li DH, Depoortere RY, Emmett-Oglesby MW (1994). Tolerance to the reinforcing effects of cocaine in a progressive ratio paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 116: 326–332.

Liu Y, Roberts DC, Morgan D (2005). Effects of extended-access self-administration and deprivation on breakpoints maintained by cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179: 644–651.

Liu Y, Roberts DC, Morgan D (2005). Sensitization to the reinforcing effects of self-administered cocaine: effects of dose and intravenous injection speed (in press).

Lorrain DS, Arnold GM, Vezina P (2000). Previous exposure to amphetamine increases incentive to obtain the drug: long-lasting effects revealed by the progressive ratio schedule. Behav Brain Res 107: 9–19.

Mateo Y, Lack CM, Morgan D, Roberts DC, Jones SR (2005). Reduced dopamine terminal function and insensitivity to cocaine following cocaine binge self-administration and deprivation. Neuropsychopharmacology. DOI:10.1038/sj.npp.1300687.

Mendelson JH, Mello NK (1996). Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. N Engl J Med 334: 965–972.

Mendrek A, Blaha CD, Phillips AG (1998). Pre-exposure of rats to amphetamine sensitizes self-administration of this drug under a progressive ratio schedule. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 135: 416–422.

Morgan D, Brebner K, Lynch WJ, Roberts DC (2002). Increases in the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine after particular histories of reinforcement. Behav Pharmacol 13: 389–396.

Morgan D, Roberts DC (2004). Sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine following binge-abstinent self-administration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 803–812.

Morgan D, Smith MA, Roberts DC (2005). Binge self-administration and deprivation produces sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 178: 309–316.

Phillips AG, Di Ciano P (1996). Behavioral sensitization is induced by intravenous self-administration of cocaine by rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 124: 279–281.

Pierce RC, Born B, Adams M, Kalivas PW (1996). Repeated intra-ventral tegmental area administration of SKF-38393 induces behavioral and neurochemical sensitization to a subsequent cocaine challenge. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278: 384–392.

Pierce RC, Kalivas PW (1995). Amphetamine produces sensitized increases in locomotion and extracellular dopamine preferentially in the nucleus accumbens shell of rats administered repeated cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275: 1019–1029.

Richardson NR, Roberts DC (1996). Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 66: 1–11.

Ridenour TA, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL, Cunningham-Williams RM (2003). Is there a progression from abuse disorders to dependence disorders? Addiction 98: 635–644.

Roberts DC, Brebner K, Vincler M, Lynch WJ (2002). Patterns of cocaine self-administration in rats produced by various access conditions under a discrete trials procedure. Drug Alcohol Depend 67: 291–299.

Roberts DC, Goeders NE (1989). Drug self-administration: experimental methods and determinants. In: Greenshaw AJ (ed). Neuromethods: Psychopharmacology. Humana: Clifton, pp 349–398.

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993). The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 18: 247–291.

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (2003). Addiction. Annu Rev Psychol 54: 25–53.

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (2004). Incentive-sensitization and drug ‘wanting’. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171: 352–353.

Samaha AN, Li Y, Robinson TE (2002). The rate of intravenous cocaine administration determines susceptibility to sensitization. J Neurosci 22: 3244–3250.

Samaha AN, Mallet N, Ferguson SM, Gonon F, Robinson TE (2004). The rate of cocaine administration alters gene regulation and behavioral plasticity: implications for addiction. J Neurosci 24: 6362–6370.

Samaha AN, Robinson TE (2005). Why does the rapid delivery of drugs to the brain promote addiction? Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 82–87.

Schenk S, Snow S, Horger BA (1991). Pre-exposure to amphetamine but not nicotine sensitizes rats to the motor activating effect of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 103: 62–66.

Stafford D, LeSage MG, Glowa JR (1998). Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: a review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 139: 169–184.

Suto N, Austin JD, Tanabe LM, Kramer MK, Wright DA, Vezina P (2002). Previous exposure to VTA amphetamine enhances cocaine self-administration under a progressive ratio schedule in a D1 dopamine receptor dependent manner. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 970–979.

Suto N, Tanabe LM, Austin JD, Creekmore E, Vezina P (2003). Previous exposure to VTA amphetamine enhances cocaine self-administration under a progressive ratio schedule in an NMDA, AMPA/kainate, and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent manner. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 629–639.

Tanabe LM, Suto N, Creekmore E, Steinmiller CL, Vezina P (2004). Blockade of D2 dopamine receptors in the VTA induces a long-lasting enhancement of the locomotor activating effects of amphetamine. Behav Pharmacol 15: 387–395.

Vanderschuren LJ, Everitt BJ (2004). Drug seeking becomes compulsive after prolonged cocaine self-administration. Science 305: 1017–1019.

Vanderschuren LJ, Schmidt ED, De Vries TJ, Van Moorsel CA, Tilders FJ, Schoffelmeer AN (1999). A single exposure to amphetamine is sufficient to induce long-term behavioral, neuroendocrine, and neurochemical sensitization in rats. J Neurosci 19: 9579–9586.

Vezina P (2004). Sensitization of midbrain dopamine neuron reactivity and the self-administration of psychomotor stimulant drugs. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 827–839.

Vezina P, Lorrain DS, Arnold GM, Austin JD, Suto N (2002). Sensitization of midbrain dopamine neuron reactivity promotes the pursuit of amphetamine. J Neurosci 22: 4654–4662.

Wagner FA, Anthony JC (2002). From first drug use to drug dependence; developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacology 26: 479–488.

Zapata A, Chefer VI, Ator R, Shippenberg TS, Rocha BA (2003). Behavioural sensitization and enhanced dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens after intravenous cocaine self-administration in mice. Eur J Neurosci 17: 590–596.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to DCSR (R01DA14030 and DA06643) and DM (K01DA13957).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, D., Liu, Y. & Roberts, D. Rapid and Persistent Sensitization to the Reinforcing Effects of Cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 121–128 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300773

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300773

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

S-Equol mitigates motivational deficits and dysregulation associated with HIV-1

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

D-amphetamine maintenance treatment goes a long way: lasting therapeutic effects on cocaine behavioral effects and cocaine potency at the dopamine transporter

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)

-

Intermittent access cocaine self-administration produces psychomotor sensitization: effects of withdrawal, sex and cross-sensitization

Psychopharmacology (2020)

-

HIV-1 proteins dysregulate motivational processes and dopamine circuitry

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

High and escalating levels of cocaine intake are dissociable from subsequent incentive motivation for the drug in rats

Psychopharmacology (2018)