Abstract

Although there is evidence for the involvement of dopamine (DA) in unipolar depression, no published study has yet used the technique of acute phenylalanine and tyrosine depletion (APTD), a dietary intervention that selectively lowers DA synthesis, in order to investigate the role of DA in mood disturbance. Tyrosine and phenylalanine depleted and placebo amino acid drinks were administered to 20 patients recovered from depression in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design. Measures included subjective effects, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores, and a comprehensive battery of well-validated computerized cognitive tests. APTD induced a substantial reduction in the ratio of plasma tyrosine and phenylalanine to large neutral amino acids. However, relapse of depressive symptoms was not seen. Although performance on most cognitive tests was unaffected, there was a selective effect on decision-making, with APTD causing participants to bet significantly less. In conclusion, These results suggest a specific role for the involvement of DA in reward/punishment processing in humans. While APTD did not induce relapse in any participant, it did cause patients recovered from depression to show lowered sensitivity to reward in a gambling game. It is hypothesized that tests involving reward/punishment processing are preferentially affected by DA depletion, and that a more complete account of depression is likely to result from considering the roles played by serotonin, noradrenaline, and DA in mediating the various cognitive and clinical symptoms, including anhedonia.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Biochemical models of depression have typically focused on the serotonin (5-HT) and noradrenaline (NA) systems. However, the dopamine (DA) system, with its critical role in mediating reward and motivation, is a clear candidate for investigation in relation to mood disorders. DSM-IV (Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition—American Psychiatric Association, 1994) lists the second criterion for a Major Depressive Episode (MDE) as ‘markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day’. By contrast, criteria for a Manic Episode include an ‘increase in goal-directed activity’. It has been hypothesized that these alterations in motivation and reward in the depressed and manic state may be mediated by hypo- and hyperfunction of the DA system, respectively (Miller, 1993; Naranjo et al, 2001; Willner, 1995).

Dysfunctional reward systems, relating to the core symptom of anhedonia, implicate a key role for DA in depression, supported by a number of lines of evidence from experimental animals and humans. In rats, chronic stress models of depression leading to learned helplessness are associated with lasting reductions in extracellular DA levels in the nucleus accumbens (Gambarana et al, 1999; Mangiavacchi et al, 2001). In humans, the most convincing evidence of a role for DA in depression is provided by the efficacious antidepressant effects of the DA agonists piribedil and bromocriptine, particularly in patients with low pretreatment cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) homovanillic acid (HVA), a major DA metabolite (Corrigan et al, 2000; Post et al, 1978; Waehrens and Gerlach, 1981). In addition, many studies have reported low CSF HVA levels in depression, especially in patients with marked psychomotor retardation (Brown and Gershon, 1993; Reddy et al, 1992). However, it is difficult to interpret such results since the observed reductions in DA may be a consequence of psychomotor retardation in these patients. Notably, the same relationship between low CSF HVA and psychomotor retardation has also been observed in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease (Wolfe et al, 1990). Stronger evidence of DA hypofunction in depression comes from post-mortem studies; it has been reported that unmedicated depressed suicide victims have lower dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) concentrations in the caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens (Bowden et al, 1997a), although D1 and D2 receptor binding were unchanged (Allard and Norlen 2001; Bowden et al, 1997b).

Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of DA in depression is somewhat equivocal. Five studies have investigated DA function in depression using the single photon emission computerized tomography ligand 123I-3-iodo-methoxybenzamide (123I-IBZM), a benzamine derivative with high D2/D3 receptor selectivity. Two studies reported higher specific binding of 123I-IBZM in currently depressed subjects (D'Haenen and Bossuyt, 1994; Shah et al, 1997), interpreting these increases as evidence of reduced extra-synaptic DA availability, while three found no difference to a control group (Ebert et al, 1996; Klimke et al, 1999; Parsey et al, 2001). One study reported that depressed patients have decreased 18F-DOPA uptake, which the authors interpreted as decreased presynaptic DA availability (Martinot et al, 2001). However, another reported no differences between depressed patients and controls in terms of DA release following amphetamine administration measured with 123I-IBZM (Parsey et al, 2001).

Acute phenylalanine and tyrosine depletion (APTD) is a safe, dietary intervention involving the administration of an amino-acid mixture lacking in tyrosine and phenylalanine, which can be used to selectively lower DA synthesis in humans. Although a number of studies have made use of the complementary procedure of acute tryptophan depletion to investigate the role of the 5-HT system in depression, no published study has yet investigated the effect of APTD in patients recovered from depression (Booij et al, 2003). Acute tryptophan depletion has been found to produce transient relapse of depressive symptoms in some patients recovered from major depression, in particular those recovered on serotonergic agents, and those who have suffered from more than one major depressive episode (MDE) (Bell et al, 2001; Booij et al, 2002).

APTD is thought to reduce central DA function by limiting the availability of its precursor, tyrosine. In rats, APTD reduces basal ganglia levels of tyrosine, as well as the DA metabolites HVA and DOPAC (Biggio et al, 1976). Furthermore, two recent neuroimaging studies using 11C-Raclopride, a D2 ligand displaced by endogenous DA release, have demonstrated increased striatal binding (indicative of reduced DA function) following APTD (Leyton et al, 2003; Montgomery et al, 2003).

In addition, although NA is synthesized from DA, a number of lines of evidence suggest that APTD lowers DA function without affecting NA function. Firstly, while APTD causes a marked reduction in DA efflux following administration of d-amphetamine (McTavish et al, 1999b), it does not affect the NA response to amphetamine or idazoxan in rats (McTavish et al, 1999a). Secondly, APTD does not effect the evening rise in plasma melatonin, the release of which is controlled by NA (Sheehan et al, 1996), but does raise plasma prolactin levels, indicative of DA depletion (Harmer et al, 2001). Lastly, APTD alters the subjective effects of d-amphetamine, which releases both DA and NA, but only attenuates those effects associated with DA, such as ratings of mind-race/buzz, while leaving unchanged those associated with NA, such as blood pressure and ratings of hunger (McTavish et al, 2001). However, it should be acknowledged that one study has reported a reduction in the CSF concentration of the NA metabolite 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylethylene, as well as that of HVA, following APTD in monkeys (Palmour et al, 1998).

A recent study suggested that APTD resulted in disturbances in the processing of reward/punishment cues and emotional stimuli in healthy volunteers, changes which are similar to those seen in depression (McLean et al, 2004). Healthy volunteers under conditions of APTD made faster responses to sad words compared to happy words on the Affective Go/No-go test (Murphy et al, 1999), the opposite pattern to that seen under the placebo condition, and showed an altered betting strategy on the Decision-making task (Rogers et al, 1999). This cognitive profile mirrors that previously reported in currently depressed patients (Murphy et al, 2001, 1999). However, a range of other neuropsychological tests sensitive to fronto-striatal function were unaffected, leading the authors to conclude that DA is particularly important in mediating the disruption of affect/reward-based processing seen in depression.

The present study investigated the effects of APTD on mood and cognition in patients recovered from depression in a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover design. It was predicted that APTD would lead to transient reoccurrence of certain symptoms in patients recovered from depression, in particular anhedonia. In addition, it was expected that APTD would affect performance on neuropsychological tests sensitive to processing of reward/punishment cues and emotional stimuli, while leaving other indices of cognitive function relatively unaffected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject Recruitment

Approximately 700 people with a history of depression were contacted by letter through their General Practitioner in the Cambridge and King's Lynn areas, and an additional 80 people with a confirmed diagnosis of past MDE were contacted by the Cambridge Family Study. In total, 38 individuals returned reply slips expressing an interest in taking part in the study, and were invited to a screening interview where they were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Revised) (SCID-R: Spitzer et al, 2002). Inclusion criteria were: history of at least one MDE lasting 4 months or more, with full recovery for at least the last 6 months. Exclusion criteria were: history of any other Axis 1 disorder outside a mood episode; current diagnosis of MDE; history of substance dependence; history of alcohol dependence outside a mood episode; history of head injury or other neurological diagnosis; treatment for depression or with any centrally acting drug within the last 6 months. Patients with a history of manic episodes were excluded, but those with a history of previous hypomanic episodes (Bipolar II) were included in the study. Of those who were invited for a screening interview, three did not attend the interview, three were not suitable due to incomplete remission or continued medication, three had a diagnosis of another Axis 1 disorder/head injury/neurological condition, six did not meet DSM-IV criteria for past MDE, and three were suitable for inclusion but chose not to take part in the study. A total of 20 volunteers (six male) with a history of at least one major depressive episode, in full remission, were entered into the study (age range 24–55 years). Three participants (one male) had a history of hypomanic episodes. The National Adult Reading Test (NART: Nelson, 1982) was completed by all participants. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. The majority (15/20) of participants had recovered either without medication or with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Experimental Procedure

All participants in this study were informed of the details of the procedure and risk of mood change at the prior screening interview. All participants provided informed consent on the first day of testing, and the study was approved by the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee (LREC No. 01/074) and the King's Lynn Local Research Ethics Committee (LREC No. 12/01). Participants arrived at the research center (either at the Fermoy Unit, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, King's Lynn or the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge) at approximately 0830 hours, having fasted from 0000 hours the previous night, drinking only water. Following baseline (T0) measurements of mood, cognitive function (Rapid Visual Information Processing—RVIP) and a 10 ml blood sample, participants were administered either a balanced amino-acid mixture (BAL) or an identical mixture save for the absence of tyrosine and phenylalanine (TYR) (for constituents see below). Participants attended two testing sessions, which were separated by a period of at least 1 week in order to minimize carryover effects. The amino acids were dissolved in approximately 400 cm3 tap water and mixed with 50 cm3 calogen and either blackcurrant or orange flavor to improve palatability. Both participants and researchers were blind as to the nature of the drinks. For the next 5 h, participants rested on the ward, and were allowed water ad libitum. At T5, subjects were administered a battery of neuropsychological tests.

Amino-Acid Mixtures

The quantities of amino acids in each drink were identical to those used by McLean et al (2004), who reported a substantial reduction in plasma tyrosine concentration. Amino-acid mixtures were as follows:

BAL: 15 g isoleucine, 22.5 g leucine, 17.5 g lysine, 5 g methionine, 17.5 g valine, 10 g threonine, 2.5 g tryptophan, 12.5 g tyrosine, and 12.5 g phenylalanine—total 115 g.

TYR: 15 g isoleucine, 22.5 g leucine, 17.5 g lysine, 5 g methionine, 17.5 g valine, 10 g threonine, and 2.5 g tryptophan—total 90 g.

For female participants, same ratios of amino acids were used, but with a 20% reduction in quantity to take account of lower body weight.

Biochemical Measures

Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C. Plasma total large neutral amino acid (LNAA) concentrations (tyrosine, valine, phenylalanine, isoleucine, leucine, and tryptophan) were measured by means of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence end-point detection and precolumn sample derivatization adapted from the methods of Furst et al (1990). Norvaline was used as an internal standard. The limit of detection was 5 nmol/ml using a 10 μl sample volume, and inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were <15 and <10%, respectively.

Psychological Rating Scales

Visual analog scales (Bond and Lader, 1974)

The visual analog scales (VAS) are comprised of 16 100 mm lines, each with contrasting adjectives at either end (eg happy–sad) (Bond and Lader, 1974). Participants were instructed to mark on each line a point that reflected their current state. The scales have been found to load onto three principal factors—alertness, contentedness, and calmness (Bond and Lader, 1974). Participants completed the VAS at T0 as well as at T5.

Apathy scale (McLean et al, 2004)

The Apathy scale, described in McLean et al (2004), is comprised of five 100 mm lines, ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘very’, each associated with one of the following descriptions: motivated, excited, energetic, interested,, full of initiative. Participants were instructed to mark on each line a point that reflected their current state. Participants completed the Apathy Scale at T0 as well as at T5.

Modified Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) (Hamilton, 1960)

Participants were administered a modified version of the HDRS that excluded the five symptoms that could not change over the course of the study day (insomnia initial, insomnia middle, insomnia late, genital symptoms, loss of weight), lowering the number of questions from 21 to 16. Hence, the maximum possible score was reduced from 61 to 49. Participants were administered the HDRS at T0 as well as at T5.

Neuropsychological Assessment

All participants were assessed on the same battery of neuropsychological tests as detailed in Table 2. As all tests used in this study have been described elsewhere, only a brief description is given of each. All participants sat approximately 60 cm from a touch-sensitive computer screen controlled by an Avantech Pentium personal computer (Model PPC-120T-RT). Half the participants carried out the tests in the order as listed in Table 2, while half carried them out in the reverse order, other than the RVIP, which was always administered first. For all tests where the order of stages, blocks, or trials could vary, order was counterbalanced across drink order.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 10 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). This study employed a within-subjects, placebo-controlled crossover design, with repeated measures on various indices of cognitive function (eg level of difficulty, stage of test). Therefore, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed where test assumptions were met (ie if variances were equivalent and data were normally distributed). In general, drink (BAL/TYR) and stage of test were entered as within-subjects factors. Drink order (TYR/BAL or BAL/TYR) and battery order (forward/reverse) were fully counterbalanced, but were initially entered as between-subjects factors. If the main effect of drink order/battery order and interactions involving drink order/battery order were found to be nonsignificant, data were collapsed across drink order/battery order for analysis of within-subjects effects. Post hoc analyses for within-subjects comparisons were carried out by constructing appropriate one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs for each comparison of interest, as recommended in Howell (2002, p. 490). In cases where there was a departure from the assumption of homogeneity of covariance in the repeated-measures ANOVA, an epsilon (ɛ) factor was calculated and used to adjust degrees of freedom accordingly. The Greenhouse–Geisser procedure for adjusting degrees of freedom was used, unless the value calculated was near or above 0.75, in which case the Huynh–Felt procedure was used (Howell, 2002). The index of variation preferred for within-subjects designs is not the standard error of the mean (SEM), but the standard error of the difference between means (SED), calculated according to the formula SED=√{(2 × MSe)/N}, where MSe is the mean squared error term from the repeated-measures ANOVA and N is the number of subjects. Practice effects can confound crossover designs, and any effects of treatment were confirmed using between-subjects comparisons on only first session data if an interaction of drink order by treatment was also found. Where appropriate, data were transformed prior to analysis as appropriate to reduce skew and stabilize variances, although data presented are untransformed values.

RESULTS

As already noted, three participants failed to complete both testing sessions. Of the remaining 17 participants, eight were administered the BAL mixture first and nine were administered the TYR mixture first. These groups did not differ in terms of age (t15=1.4, p=0.18) or NART IQ (t15=1.4, p=0.17). Nor did these groups differ in terms of number of depressive episodes, mean length of depressive episode, length of remission, total time depressed, age of onset of depression, number of patients experiencing suicidal ideation, or number of patients attempting suicide (p>0.2 for all) (see Table 1).

Of the 17 participants who completed both testing sessions, computer failure caused a loss of data for some tests. Numbers of participants completing all stages of each neuropsychological test at all time-points were as follows: RVIP—14; PRM—17; Decision-making—16; Affective Go/No-go—16; One-touch Tower of London—16; Probabilistic Reversal—17. In addition, amino-acid analyses were not available at all four time-points for five participants due to difficulties with blood extraction.

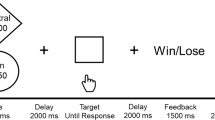

Biochemical Measures

Statistics are based on the measure of tyrosine availability to the brain, measured by calculating the ratio of tyrosine and phenylalanine concentrations combined, to those of other LNAAs (leucine, isoleucine, tryptophan, and valine) (TP : LNAA ratio—see Table 3) (Harmer et al, 2001). There was a significant main effect of time (F1,11=34.4, p<0.001), a significant main effect of treatment (F1,11=8.9, p=0.012), and a significant treatment × time interaction (F1,11=20.5, p<0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that TYR and BAL did not differ on TP : LNAA ratio at T0 (F1,11<1), while at T5 TP : LNAA ratio was significantly reduced following TYR compared to BAL (F1,11=24.0, p<0.001) (see Figure 1).

Tyrosine availability to the brain (the ratio of tyrosine and phenylalanine concentrations combined, to those of the other large neutral amino acids) fell from T0 (baseline) to T5 (immediately prior to testing) to a significantly greater extent when TYR (tyrosine/phenylalanine-depleted drink) was administered compared to when BAL (placebo drink) was administered. Bars represent the mean, error bars 1 SED.

Psychological Rating Scales

Table 3 details HDRS scores, mean VAS factor scores of alertness, contentedness and calmness, and apathy scale scores at the four time-points. HDRS score was not affected by time (F1,15<1) or treatment (F1,15=3.2, p=0.098) with no treatment × time interaction (F1,15<1).

For the VAS, participants felt significantly less alert at T5 compared to T0 (F1,15=15.2, p<0.001), with no effect of treatment (F1,15<1) or treatment × time interaction (F1,15<1). Contentedness was unaffected by time or treatment (p>0.1 for all effects). Participants felt significantly less calm at T5 compared to T0 (F1,15=19.0, p<0.001), with no effect of treatment (F1,15<1) or treatment × time interaction (F1,15<1). Participants felt significantly more apathetic at T5 compared to T0 (F1,15=17.4, p<0.001), with no effect of treatment (F1,15<1) or treatment × time interaction (F1,15<1). In summary, none of the subjective measures were affected differently by TYR compared to BAL.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Table 4 details scores for all neuropsychological tests employed in this study, except the RVIP, data for which can be found in Table 3. Battery order (forward/reverse) was entered as a between-subjects measure for all tests other than RVIP (which was always administered first).

Rapid Visual Information Processing

There was a significant effect of time on A′ (F1,12=12.1, p=0.005), with no main effect of treatment (F1,12=1.4, p=0.21) and a significant time × treatment interaction (F1,12=8.3, p=0.014). Post hoc analyses indicated that there was no difference in A′ at T0 when TYR was to be administered compared to when BAL was to be administered (F1,12=1.2, p=0.29), but at T5, A′ was higher following BAL than following TYR (F1,12=8.9, p=0.011). In addition, A′ improved from T0 to T5 when BAL was administered (F1,12=19.0, p<0.001), but not when TYR was administered (F1,12<1) (see Figure 2a). Participants improved A′ on the second session compared to the first session (treatment × drink order interaction F1,12=39.6, p<0.001).

(a) Rapid Visual Information Processing A′ (sensitivity). Participants improved A′ from T0 (baseline) to T5 (immediately prior to testing) when administered BAL (placebo drink) to a significantly greater extent than when administered TYR (tyrosine/phenylalanine-depleted drink). Bars represent the mean, error bars 1 SED. (b) Rapid Visual Information Processing Latency. Participants were quicker at T5 (immediately prior to testing) compared to T0 (baseline) when administered BAL (placebo drink), but not when administered TYR (tyrosine/phenylalanine-depleted drink). Bars represent the mean, error bars 1 SED.

Two participants scored maximum hits and no false alarms on at least one session, and therefore B″ could be calculated for only 12 participants. B″ was unaffected by treatment or time (p>0.1 for all effects).

There was a trend towards a significant main effect of time on latency (F1,12=3.7, p=0.079), with no main effect of treatment (F1,12=1.1, p=0.31) and a significant time × treatment interaction (F1,12=8.2, p=0.014). Post hoc analyses indicated that there was no difference in latency at T0 when BAL was to be administered compared to when TYR was to be administered, but at T5, participants were quicker following BAL than following TYR (F1,12=10.0, p=0.008). In addition, participants made faster responses at T5 compared to T0 when BAL was administered (F1,13=7.3, p=0.018) but not when TYR was administered (F1,13<1) (see Figure 2b). Participants were quicker on the second session compared to the first (treatment × drink order interaction F1,12=8.0, p=0.015).

Owing to the improvement on session 2 compared to session 1 for A′ and latency, restricted analyses were carried out for session 1 data only to confirm the time × treatment interaction. For A′, the improvement from T0 to T5 for participants administered BAL was greater than that for participants administered TYR (F1,15=2.0, p=0.061). For latency, the quickening from T0 to T5 for participants administered BAL was greater than that for participants administered TYR (F1,15=20.0, p<0.001). Therefore, only session 1 analyses confirmed the detrimental effect of APTD on A′ and latency.

Pattern Recognition Memory

Pattern Recognition Memory was unaffected by TYR. Participants were less accurate at the delayed stage of the task (F1,16=61.5, p<0.001), with no main effect of treatment (F1,16=2.2, p=0.16) and no treatment × delay interaction (F1,16<1). There were no significant effects for response latency (F1,16<1 for all).

Decision-making task

Quality of decision making (choice of the most likely outcome) was unaffected by treatment (F1,15<1) or condition (F1,15<1), but participants increased the choice of the most likely gamble as ratio increased (F2.0,30.7=5.4, p=0.0092, ɛ=0.68). All interaction effects were nonsignificant (p>0.1 for all).

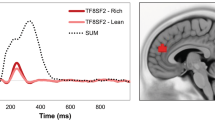

Participants bet less when administered TYR compared to when they were administered BAL (F1,15=12.0, p=0.004) (see Figure 3). In addition, there was a significant main effect of ascend/descend condition (F1,15=103.7, p<0.001) and of ratio (F1.5,22.7=82.3, p<0.001, ɛ=0.50), and a significant condition × ratio interaction (F2.8,634.8=4.8, p=0.007, ɛ=0.93). As expected, participants bet more in the descend condition than in the ascend condition and increased bets as a function of ratio, but did so to a greater extent in the ascend condition than in the descend condition. No other interaction effects were significant (p>0.1 for all).

Response latency was unaffected by treatment (F1,14<1) and condition (F1,14<1), but participants reduced response latency as ratio increased (F3,42=5.1, p=0.004, ɛ=1). A treatment × condition × ratio interaction was also present (F2.9,41.6=3.5, p=0.025, ɛ=0.97), but post hoc analyses failed to confirm the significance of this effect. Participants also reduced latency on the second testing session (treatment × drink order interaction, F1,14=5.2, p=0.039). There were no significant interactions with treatment (p>0.1 for all).

Affective Go/No-go test

Response latency, commission errors, omission errors, and all interaction effects were unaffected by TYR (p>0.1 for all). ‘Affective bias’ measures were calculated by subtracting the mean happy reaction time from the mean sad reaction time, after McLean et al (2004). Participants showed a positive affective bias when administered BAL, and a small negative affective bias when administered TYR, a difference that showed a trend towards significance (t16=1.5, p=0.081, one-tailed).

One-touch Tower of London

Moves per problem was unaffected by treatment (F1,15<1) and increased with difficulty level (F1.8,26.4=10.9, p<0.001, ɛ=0.35), with no treatment × difficulty interaction (F2.9,43.3<1, ɛ=0.58).

Response latency was also unaffected by treatment (F1,14<1), and increased with difficulty level (F1.6,23.0=75.3, p<0.0001, ɛ=0.33) with no treatment × difficulty interaction (F1.9,27.0=1.0, p=0.37, ɛ=0.39). Participants decreased latency on the second testing session (treatment × order interaction F1,14=7.8, p=0.014), particularly at the harder problems (treatment × difficulty × order interaction F1.9,27.0=4.8, p=0.018, ɛ=0.39).

Probabilistic Reversal

Three subjects failed to reach criterion on at least one of the stages of this task having been administered TYR. As reaching criterion is necessary to calculate the measures arising from this test, the following analyses are based on data from 14 participants. Perseverative errors and response latency were unaffected by treatment (F1,13<1 and F1,12=1.3, p=0.27 respectively), but participants reduced response latency on the second testing session (treatment × order reaction F1,12=7.3, p=0.019).

Maintenance error score was unaffected by treatment (F1,13<1) and stage (F1,13<1), with no treatment × stage interaction (F1,13=1.6, p=0.23). Probability of shifting following positive and negative feedback were both unaffected by treatment (F1,13<1 for both) and stage (F1,13=3.2, p=0.10 and F1,13<1 respectively), with no treatment × stage interaction (F1,13<1 for both).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, no other published study has investigated the physiological, subjective, and cognitive effects of APTD in patients recovered from depression. The primary finding was that, unlike acute tryptophan depletion, APTD did not cause a marked lowering of mood in any participant. Therefore, these data suggest that DA does not play as great a role as 5-HT in the production of depressive symptoms, at least as measured by the HDRS. Following both APTD and placebo, participants reported feeling less alert, less calm, and more apathetic than at baseline. However, these effects were no more marked following APTD than following placebo. This is somewhat surprising since previous studies in healthy volunteers have reported that APTD leads to decreased contentedness and increased apathy (McLean et al, 2004). The effects observed are probably attributable to the rigours of the test day, such as the restricted diet and prolonged periods of physical inactivity.

Despite the apparent lack of effect on subjective rating-scales, APTD resulted in a robust reduction in risk-taking behavior on the Decision-making task, but did not change response latency or choice of the most likely outcome (see Figure 3 and Table 4). We hypothesize that APTD, via a reduction in DA synthesis, caused a state akin to anhedonia in patients recovered from depression, and that participants in this study bet less following APTD due to a reduction in reward sensitivity. However, it is also possible that participants showed reduced betting following APTD due to increased expectation of punishment, consistent with the commonly noted clinical characteristic of pessimism. Further studies are required to establish whether this change in behavior is due to decreased sensitivity to reward or increased expectation of punishment, or perhaps both. Whatever the mechanisms underlying this alteration in reward processing, it appears that objective cognitive measures are more sensitive to changes in internal state following neurochemical manipulation than subjective rating-scales.

It is of interest to compare these results to those of McLean et al (2004), who found that APTD did not cause healthy volunteers to bet less overall, but rather caused them to increase bets more slowly with increasing ratio. In the present study such an interaction was not seen, but it is possible that patients recovered from one or more episodes of depression are more sensitive to DA depletion following APTD than healthy controls, leading to a more pronounced change in behavior on the Decision-making task.

APTD had no effect on immediate or delayed Pattern Recognition Memory in this study, but did affect performance on the RVIP. APTD caused participants to respond more slowly and less accurately (see Figure 2 and Table 3). In contrast, APTD did not cause any significant change to response bias (B″), although subjects were close to ceiling on this measure. Previous studies employing APTD in healthy volunteers have not reported any effect on the RVIP (Harmer et al, 2001; McLean et al, 2004), although it is possible that patients recovered from depression are more sensitive to APTD. This finding is of particular interest given that target sensitivity and response latency on the RVIP are both affected in bipolar disorder, and may be thought of as trait markers, since impairment on these measures persists in the euthymic stage and survives partial correlation for residual symptoms (Clark et al, 2002). The current study suggests that this impairment could be due to decreased DA function in bipolar patients, even in the absence of any affective symptoms.

On the Affective Go/No-go test, APTD caused participants to show a trend towards a negative affective bias. It is likely that this effect might reach significance in a larger sample, since healthy volunteers also show a significant negative affective bias following APTD (McLean et al, 2004). It is of interest that APTD caused a bias towards negative words in patients recovered from depression, as this bias is also seen in currently depressed patients (Murphy et al, 1999). Following placebo, participants showed a positive bias, which is important since healthy volunteers also show a slight positive bias, which may represent a resilience buffer against the damaging psychological effects of negative life events (Chamberlain and Sahakian, 2004).

APTD did not cause altered response to negative feedback on the Probabilistic Reversal task in this study, as previously reported in depressed patients (Elliott et al, 1997b; Murphy et al, 2003). Neither did APTD increase latency to respond, as previously reported following acute tryptophan depletion in healthy volunteers (Murphy et al, 2002). In addition, APTD did not produce any impairment in either accuracy or latency on the One-touch Tower of London task. This finding concurs with McLean et al (2004), who also did not report any effects of APTD on the same task in healthy volunteers. The lack of an effect is somewhat surprising given that depressed patients perform poorly on the task (Elliott et al, 1997a, 1997b), and other dopaminergic manipulations do produce detrimental performance on both this and other ‘frontal-executive’ tasks (Harmer et al, 2001; Mehta et al, 1999). However, the mediation of performance on frontal-executive tasks by dopaminergic manipulation has produced inconsistent results, and may depend on the specific drug used and dosage (Robbins, 2000).

A number of studies have found that administration of the tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor alpha-methylparatyrosine (AMPT), which causes depletion of both DA and NA, causes depressive relapse in patients recovered on selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), but not those recovered on SSRIs (Berman et al, 1999; Bremner et al, 2003; Miller et al, 1996). However, it is likely that AMPT treatment is causing relapse in these patients primarily via noradrenergic, rather than dopaminergic mechanisms, as AMPT treatment of more than 24 h is necessary to produce such relapse. Tyrosine depletion, by contrast, is thought to preferentially cause DA depletion, while leaving NA unchanged (McTavish et al, 1999a). In the present study, most patients had recovered either without medication or on SSRIs. It would be of interest in future studies to examine the effects of APTD on patients recovered on SNRIs.

Summary

In this study, patients free of medication who had recovered from major depression were administered either a balanced amino-acid drink or one lacking in tyrosine and phenylalanine, in a within-subjects double-blind crossover design. Administration of TYR resulted in a substantial drop in plasma tyrosine/phenylalanine levels and particularly the TP : LNAA ratio. However, no subjective changes were apparent, and, in contrast to the effect caused by acute tryptophan depletion, APTD did not induce relapse of symptoms in any participant. APTD did induce a number of cognitive changes in patients recovered from depression; in particular, participants showed a trend towards a negative bias on the Affective Go/No-go test, and significantly reduced betting on the Decision-making task, which is hypothesized to be due to decreased sensitivity to reward, akin to the symptom of anhedonia. In addition, APTD caused participants to respond less accurately and more slowly on the RVIP. However, no significant effects were seen on tests of memory, planning, or response to negative feedback. The results of this study support the hypothesis that tasks involving processing of reward/punishment cues and emotional stimuli are particularly sensitive to APTD, and that insensitivity to reward, relating to the core depressive symptom of anhedonia, is mediated in part by a reduction in DA availability. These data indicate that depression cannot be explained by appealing to a deficiency in a single neurotransmitter system, but rather that the various emotional and cognitive symptoms seen in depression are the result of a complex interaction of 5-HT, NA, and DA dysfunction (see also Berman et al, 2002). Future attempts to explain the neurochemical modulation of depression should integrate findings that explicate the roles of these three neurotransmitters in the production and maintenance of the various emotional and cognitive symptoms.

References

Allard P, Norlen M (2001). Caudate nucleus dopamine D(2) receptors in depressed suicide victims. Neuropsychobiology 44: 70–73.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC.

Bell C, Abrams J, Nutt D (2001). Tryptophan depletion and its implications for psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 178: 399–405.

Berman RM, Narasimhan M, Miller HL, Anand A, Cappiello A, Oren DA et al (1999). Transient depressive relapse induced by catecholamine depletion: potential phenotypic vulnerability marker? Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 395–403.

Berman RM, Sanacora G, Anand A, Roach LM, Fasula MK, Finkelstein CO et al (2002). Monoamine depletion in unmedicated depressed subjects. Biol Psychiatry 51: 469–473.

Biggio G, Porceddu ML, Gessa GL (1976). Decrease of homovanillic, dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and cyclic-adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate content in the rat caudate nucleus induced by the acute administration of an aminoacid mixture lacking tyrosine and phenylalanine. J Neurochem 26: 1253–1255.

Bond A, Lader M (1974). The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br J Med Psychol 47: 211–218.

Booij L, Van der Does AJ, Riedel WJ (2003). Monoamine depletion in psychiatric and healthy populations: review. Mol Psychiatry 8: 951–973.

Booij L, Van der Does W, Benkelfat C, Bremner JD, Cowen PJ, Fava M et al (2002). Predictors of mood response to acute tryptophan depletion. A reanalysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 852–861.

Bowden C, Cheetham SC, Lowther S, Katona CL, Crompton MR, Horton RW (1997a). Reduced dopamine turnover in the basal ganglia of depressed suicides. Brain Res 769: 135–140.

Bowden C, Theodorou AE, Cheetham SC, Lowther S, Katona CL, Crompton MR et al (1997b). Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor binding sites in brain samples from depressed suicides and controls. Brain Res 752: 227–233.

Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Ng CK, Vermetten E, Nazeer A, Oren DA et al (2003). Regional brain metabolic correlates of alpha-methylparatyrosine-induced depressive symptoms: implications for the neural circuitry of depression. JAMA 289: 3125–3134.

Brown AS, Gershon S (1993). Dopamine and depression. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 91: 75–109.

Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ (2004). Cognition in Depression and Mania, Solvay Cognition Conference. IOP Press: London.

Clark L, Iversen SD, Goodwin GM (2002). Sustained attention deficit in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 180: 313–319.

Corrigan MH, Denahan AQ, Wright CE, Ragual RJ, Evans DL (2000). Comparison of pramipexole, fluoxetine, and placebo in patients with major depression. Depress Anxiety 11: 58–65.

D'Haenen HA, Bossuyt A (1994). Dopamine D2 receptors in depression measured with single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry 35: 128–132.

Ebert D, Feistel H, Loew T, Pirner A (1996). Dopamine and depression—striatal dopamine D2 receptor SPECT before and after antidepressant therapy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 126: 91–94.

Elliott R, Baker SC, Rogers RD, O'Leary DA, Paykel ES, Frith CD et al (1997a). Prefrontal dysfunction in depressed patients performing a complex planning task: a study using positron emission tomography. Psychol Med 27: 931–942.

Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, Herrod JJ, Robbins TW, Paykel ES (1997b). Abnormal response to negative feedback in unipolar depression: evidence for a diagnosis specific impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 63: 74–82.

Furst P, Pollack L, Graser TA, Godel H, Stehle P (1990). Appraisal of four pre-column derivatization methods for the high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of free amino acids in biological materials. J Chromatogr 499: 557–569.

Gambarana C, Masi F, Tagliamonte A, Scheggi S, Ghiglieri O, De Montis MG (1999). A chronic stress that impairs reactivity in rats also decreases dopaminergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens. A microdialysis study. J Neurochem 72: 2039–2046.

Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry 23: 56–62.

Harmer CJ, McTavish SFB, Clark L, Goodwin GM, Cowen PJ (2001). Tyrosine depletion attenuates dopamine function in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 154: 105–111.

Howell DC (2002). Statistical Methods for Psychology, 5th edn. Duxbury Press: London.

Klimke A, Larisch R, Janz A, Vosberg H, Muller-Gartner HW, Gaebel W (1999). Dopamine D2 receptor binding before and after treatment of major depression measured by [123I]IBZM SPECT. Psychiatry Res 90: 91–101.

Leyton M, Dagher A, Boileau I, Casey K, Baker GB, Diksic M et al (2003). Decreasing amphetamine-induced dopamine release by acute phenylalanine/tyrosine depletion: a PET/[(11)C]raclopride study in healthy men. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 427–432.

Mangiavacchi S, Masi F, Scheggi S, Leggio B, De Montis MG, Gambarana C (2001). Long-term behavioral and neurochemical effects of chronic stress exposure in rats. J Neurochem 79: 1113–1121.

Martinot M, Bragulat V, Artiges E, Dolle F, Hinnen F, Jouvent R et al (2001). Decreased presynaptic dopamine function in the left caudate of depressed patients with affective flattening and psychomotor retardation. Am J Psychiatry 158: 314–316.

McLean A, Rubinsztein JS, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2004). The effects of tyrosine depletion in normal healthy volunteers: implications for unipolar depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171: 286–297.

McTavish SFB, Callado L, Cowen PJ, Sharp T (1999a). Comparison of the effects of alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine and a tyrosine-free amino acid load on extracellular noradrenaline in the rat hippocampus in vivo. J Psychopharmacol 13: 379–384.

McTavish SFB, Cowen PJ, Sharp T (1999b). Effect of a tyrosine-free amino acid mixture on regional brain catecholamine synthesis and release. Psychopharmacology 141: 182–188.

McTavish SFB, McPherson MH, Harmer CJ, Clark L, Sharp T, Goodwin GM et al (2001). Antidopaminergic effects of dietary tyrosine depletion in healthy subjects and patients with manic illness. Br J Psychiatry 179: 356–360.

Mehta MA, Sahakian BJ, McKenna PJ, Robbins TW (1999). Systemic sulpiride in young adult volunteers simulates the profile of cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146: 162–174.

Miller HL, Delgado PL, Salomon RM, Berman R, Krystal JH, Heninger GR et al (1996). Clinical and biochemical effects of catecholamine depletion on antidepressant-induced remission of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 117–128.

Miller R (1993). Striatal dopamine in reward and attention: a system for understanding the symptomatology of acute schizophrenia and mania. Int Rev Neurobiol 35: 161–278.

Montgomery AJ, McTavish SF, Cowen PJ, Grasby PM (2003). Reduction of brain dopamine concentration with dietary tyrosine plus phenylalanine depletion: an [(11)C]raclopride PET study. Am J Psychiatry 160: 1887–1889.

Murphy FC, Michael A, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2003). Neuropsychological impairment in patients with major depressive disorder: the effects of feedback on task performance. Psychol Med 33: 455–467.

Murphy FC, Rubinsztein JS, Michael A, Rogers RD, Robbins TW, Paykel ES et al (2001). Decision-making cognition in mania and depression. Psychol Med 31: 679–693.

Murphy FC, Sahakian BJ, Rubinsztein JS, Michael A, Rogers RD, Robbins TW et al (1999). Emotional bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychol Med 29: 1307–1321.

Murphy FC, Smith KA, Cowen PJ, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2002). The effects of tryptophan depletion on cognitive and affective processing in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 163: 42–53.

Naranjo CA, Tremblay LK, Busto UE (2001). The role of the brain reward system in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 25: 781–823.

Nelson HE (1982). National Adult Reading Test (NART): Test Manual. NFER-Nelson: Windsor.

Palmour RM, Ervin FR, Baker GB, Young SN (1998). An amino acid mixture deficient in phenylalanine and tyrosine reduces cerebrospinal fluid catecholamine metabolites and alcohol consumption in vervet monkeys. Psychopharmacology 136: 1–7.

Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Zea-Ponce Y, Rodenhiser J, Kegeles LS, Pratap M et al (2001). Dopamine D(2) receptor availability and amphetamine-induced dopamine release in unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 50: 313–322.

Post RM, Gerner RH, Carman JS, Gillin JC, Jimerson DC, Goodwin FK et al (1978). Effects of a dopamine agonist piribedil in depressed patients: relationship of pretreatment homovanillic acid to antidepressant response. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35: 609–615.

Reddy PL, Khanna S, Subhash MN, Channabasavanna SM, Rao BS (1992). CSF amine metabolites in depression. Biol Psychiatry 31: 112–118.

Robbins TW (2000). Chemical neuromodulation of frontal-executive functions in humans and other animals. Exp Brain Res 133: 130–138.

Rogers RD, Everitt BJ, Baldacchino A, Blackshaw AJ, Swainson R, Wynne K et al (1999). Dissociable deficits in the decision-making cognition of chronic amphetamine abusers, opiate abusers, patients with focal damage to prefrontal cortex, and tryptophan-depleted normal volunteers: evidence for monoaminergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 20: 322–339.

Shah PJ, Ogilvie AD, Goodwin GM, Ebmeier KP (1997). Clinical and psychometric correlates of dopamine D2 binding in depression. Psychol Med 27: 1247–1256.

Sheehan BD, Tharyan P, McTavish SFB, Campling GM, Cowen PJ (1996). Use of a dietary manipulation to deplete plasma tyrosine and phenylalanine in healthy subjects. J Psychopharmacol 10: 231–234.

Spitzer MB, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002). Stuctured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). Biometrics Research, New York State Biometrics Institute: New York.

Waehrens J, Gerlach J (1981). Bromocriptine and imipramine in endogenous depression. A double-blind controlled trial in out-patients. J Affect Disord 3: 193–202.

Willner P (1995). Dopaminergic mechanisms in depression and mania. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ (eds). Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Raven Press: New York. pp 921–931.

Wolfe N, Katz DI, Albert ML, Almozlino A, Durso R, Smith MC et al (1990). Neuropsychological profile linked to low dopamine: in Alzheimer's disease, major depression, and Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 53: 915–917.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Program Grant (Number 019407) to Trevor Robbins, Barbara Sahakian, Barry Everitt, and Angela Roberts, and was completed within the MRC Centre for Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience. Andrew Blackwell was supported by the same grant. Barbara Sahakian is a consultant for Cambridge Cognition. Jonathan Roiser was funded by a Medical Research Council Studentship. Ian Goodyer and Diane Bamber were supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (Number 053642) and a Heath Foundation Project grant. Many thanks to Caroline Humphries and all the staff at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Addenbrooke's Hospital, for their help and support. We would like to express our gratitude to Dr Antony Warren and colleagues at the Lensfield Medical Practice, Cambridge, for assistance in recruitment, and to Dr Graham Murray for clinical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roiser, J., McLean, A., Ogilvie, A. et al. The Subjective and Cognitive Effects of Acute Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Depletion in Patients Recovered from Depression. Neuropsychopharmacol 30, 775–785 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300659

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300659

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Metabolomic changes in animal models of depression: a systematic analysis

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)

-

Post-inflammatory behavioural despair in male mice is associated with reduced cortical glutamate-glutamine ratios, and circulating lipid and energy metabolites

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Efficacy of Pharmacological Interventions in Targeting Decision-Making Impairments across Substance and Behavioral Addictions

Neuropsychology Review (2019)

-

Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: a transdiagnostic approach

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2018)

-

Discovery, screening and evaluation of a plasma biomarker panel for subjects with psychological suboptimal health state using 1H-NMR-based metabolomics profiles

Scientific Reports (2016)