« Prev Next »

Poster Presentations

Poster presentations may not seem as prestigious as oral presentations, but they are a great opportunity to interact with other scientists in your field in a reasonably structured way. Just like oral presentations, they force you to crystallize your thoughts about your research and, in this way, focus on its essence. After the conference, you can usually hang your poster in the hallway of your laboratory. Thus, you promote your work to passersby and have a support at hand if you must unexpectedly present your research to visitors.

Being accepted for a poster session at a conference means you must first create the poster itself, then prepare to interact with visitors during the session. At some conferences, you may also have a chance to promote your poster through an extremely brief oral presentation.

Creating your poster

Typically, the scientists who attend a poster session are wandering through a room full of posters, full of people, and full of noise. Unless they have decided in advance which posters or presenters to seek out, they will stop at whatever catches their eyes or ears, listening in on explanations given to other people and perhaps asking an occasional question of their own. They may not be able to see each poster clearly — for example, they may be viewing it from a meter's distance, from a sharp angle of incidence, or over someone else's shoulder. In such situations, they will not want to read much text on the poster — not any more than attendees at a presentation will want to read much text on a slide.

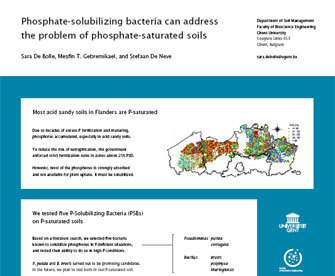

Accordingly, you should design your poster more like a set of slides than like a paper, using all the recommendations given for slides earlier in this series (see Creating Presentation Slides). Strive to get your messages across in a stand-alone way: State each message as a short sentence, then illustrate it as visually as possible. In fact, one simple way to prepare a poster is to create a set of slides, print them full-size on A4 or US-letter-size paper, and pin the sheets next to one another like a comic strip.

If you are designing your poster as one large sheet rather than a juxtaposition of small ones, you have more freedom in the way you organize your poster. Use this freedom to reveal the overall structure of your content; doing so is easier with a single sheet than with a sequence of slides. In particular, organize related pieces of content in coherent visual units. Resist the temptation to place information "wherever it fits" in a desperate attempt to include as many details as possible. Instead of crowding your poster, be selective in what you include so you have the spatial freedom to organize your material into a logical structure that is recognizable at a glance. Also, as on slides, question the usefulness of anything you plan to use, especially frames, arrows, and colors.Scientists often feel obliged to include a large amount of factual information on their posters: their affiliation (with postal address, e-mail address, telephone number, etc.), bibliographical references, funding sources, and the like. Although visitors may well want to take all or part of this information home, few of them actually want to read it on a poster, let alone write it on a notepad while standing in front of a poster. Such information is therefore best placed in a one-page handout that is available at the poster's location — perhaps with a reduced version of the poster on the other side. If these details are included on the poster itself, they should be out of the way, such as in the top-right corner or at the very bottom, so they do not interrupt the logical flow of content on the poster.

Presenting your poster

Even though a well-designed poster stands on its own, you can add value to it through your explanations and answers. Make sure visitors can link you to your poster: Position yourself next to it and wear your name badge visibly. Do not just stand there, however — take steps to attract visitors to your poster, interact with them, and wrap up the exchange before they move on.

As people start entering the room, reach out to them. Standing shyly next to your poster, waiting for questions while hoping not to get any, is not helpful to anyone. Instead, make eye contact with the people who pass, smile at them, and greet them with an inviting "hello" or "welcome." If visitors do come to your poster, give them a moment to take it in, then make it clear that you are available for discussion: Volunteer to answer questions ("If you have any questions, I'll be happy to take them.") or offer to tell your story ("Would you like me to explain the poster?").

When explaining your poster, be brief. You do not have a captive audience: With so many posters to see, visitors have only limited time for yours. If they need more information, they will let you know by asking focused questions. At that point, feel free to go into details with more specialized or more interested individuals, but also be aware of other people who may be waiting to ask you different questions — they may not wait long before deciding to move on. Strike a balance between talking in more depth with a few people and talking in less depth with more people. Be ready to give the same explanations many times as new people replace those who move on to other posters. Maintain your enthusiasm all the way to the end of the session: The last person to see your poster might be just as important as the first.

As visitors indicate their intention to move on (usually with "Thank you"), close the interaction on a positive note (such as by saying "My pleasure" or "Thank you for stopping by") and, if you have not yet done so, exchange business cards or offer them a handout. If you have made your poster or supporting material available on a Web page, be sure to display the URL of this page prominently on your handout.

Promoting your poster

Even without a formal opportunity to promote your poster, and especially when your poster session is later in the conference, you may have many informal moments to introduce your work through chance encounters during coffee breaks or social events. Instead of giving people business cards, you might prepare and distribute small, bookmark-like handouts with your name, affiliation, e-mail, and an invitation to come and see your poster.

No matter how you tell others about your work, make sure you identify your poster clearly, such as by its number. There is no point in promoting your poster if people cannot find it later.

Within this Subject (22)