Abstract

While human societies are extraordinarily cooperative in comparison with other social species, the question of why we cooperate with unrelated individuals remains open. Here we report results of a lab-in-the-field experiment with people of different ages in a social dilemma. We find that the average amount of cooperativeness is independent of age except for the elderly, who cooperate more, and a behavioural transition from reciprocal, but more volatile behaviour to more persistent actions towards the end of adolescence. Although all ages react to the cooperation received in the previous round, young teenagers mostly respond to what they see in their neighbourhood regardless of their previous actions. Decisions then become more predictable through midlife, when the act of cooperating or not is more likely to be repeated. Our results show that mechanisms such as reciprocity, which is based on reacting to previous actions, may promote cooperation in general, but its influence can be hindered by the fluctuating behaviour in the case of children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The underlying conflict between one’s own benefit and helping others poses an evolutionary conundrum1 and lies at the heart of many social dilemmas2. In particular, human societies are extraordinarily cooperative in comparison with other social species3,4,5,6. The study of this problem has been addressed in a stylized but insightful manner using the Prisoner’s Dilemma7,8, arguably the most difficult context for the emergence of cooperation: individuals are tempted to defect because of greed (the reward for cheating against a cooperator is the largest payoff in the game) and of fear (players cheated upon receive the lowest possible payoff), while mutual cooperation is the most beneficial outcome in a collective sense. From a theoretical perspective, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how cooperation can arise in such a context9,10. Prominent among those are kin selection11,12, reciprocity7,13, reputation14 and different forms of assortment15, including the greenbeard effect16 and the existence of a structure in the population17. Most of these mechanisms have a wide range of applicability, in which they successfully allow to understand cooperative behaviour. Therefore, although there is no general theory of cooperation, significant and promising progress has certainly been made.

From the experimental part, although much work has been done up to date18, many important issues are yet unresolved or even unexplored. In particular, whether or not humans’ propensity towards cooperation changes through the life cycle is a yet-to-answer challenge. This is the focus of our study. Indeed, a vast majority of experiments conducted up to now involve volunteers coming from Economics, Psychology or other academic disciplines, that is, with a high educational level and typically in the 18- to 25-year-old range (on work with different types of subjects, see, for example, refs 19 and 20). On the other hand, although there are many studies examining altruistic behaviour in children21,22,23, very little is known about how cooperative behaviour changes across generations. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one earlier study in which subjects of different ages were involved in the same experimental set-up to test their cooperativeness, namely the work by Charness and Villeval24. They conducted experiments with employees of two French firms using junior (under 30) and senior (over 50) subjects, and on a conventional laboratory set-up with students and retirees. Their main finding is that seniors were more cooperative than juniors, along with some other characteristics that imply that keeping seniors in the work force may be beneficial. We will come back to this work, very related to ours on the old-age range, in the Discussion. A few other lines of work have investigated the possible decline of decision-making abilities of older individuals as well as the relation of other social interaction contexts, such as trust, and age (see, for example, ref. 24 for references). Among the latter, the paper by Sutter and Kocher25 will also be relevant for our discussion below.

Here we address the issue of possible age dependences of the experimentally observed behaviours by conducting a lab-in-the-field experiment, in which volunteers of different ages play n-player Prisoner’s Dilemmas (PDs). As it has been recently shown that n-player PDs lead to the same qualitative results when n≥3 (ref. 26), we focused on the case of the n=4 game. For the experiments (henceforth referred to as the DAU and School experiments), subjects were placed in a group with other players of similar ages (there were seven groups) or in a group with other participants irrespective of their age (control groups).

Our results show that young teenagers do not have an intrinsic strategy and that elderly people cooperate more. Specifically, we report that there are two transitions in the observed cooperative level as humans get older: children in the range 10–16 years old are neither intrinsically cooperators nor defectors, their behaviour being influenced by their neighbourhood. In adulthood, individuals are differentiated and decisions become much more persistent. Subsequently, cooperativeness increases in the elderly. Our findings imply that mechanisms usually invoked to explain human cooperation are age-independent beyond adolescence and suggest that specific strategies should be developed to foster prosocial behaviour in youth.

Results

Experiments

In a first stage, we run an experiment during the first Board Games Fair (DAU Barcelona Festival, http://daubarcelona.bcn.cat) in December 2012 (referred to as DAU experiment). Participants with ages between 10 and 87 were randomly recruited among visitors of the Festival to play an iterated four-person PD for 25 rounds (this number was fixed but unknown to the participants). In order to compare the behaviour of subjects of different ages, we divided the age range as follows: 10–16, 17–25 (which corresponds to the typical age range in this sort of experiments) 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65 and 66 and over. In addition, the control groups had four participants irrespective of their age. Table 1 summarizes the main features of these groups. It is worth stressing that the Festival was more an exhibition and a social event than a convention aimed at attracting well-trained players. Moreover, volunteers that participated in the experiment did not know each other and did not show up by themselves, but we had to make efforts to recruit them, somewhat diminishing the possibility of self-selection. As shown below, the youngest group showed a significantly distinct behaviour with respect to the rest of the groups. Therefore, in order to reproduce the results found for the children, we subsequently carried out a sequel with the same experimental set-up at the Jesuïtes Casp (Casp Jesuits School, http://www.casp.fje.edu, hereafter referred to as School experiment), focusing on reproducing the results of the young teenager group with 53 new subjects between 12 and 13 years old. In Methods, we provide a more detailed description of the volunteer profile and recruitment at the DAU and School experiments and the experimental procedure. Full details on the software and the experiment instructions are included in the Supplementary Methods.

Average level of cooperation

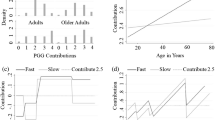

We begin the report on our results with the DAU experiment. The overall fraction of cooperative actions c in each round, averaged over all players (and, therefore, over all age groups) quickly drops from initial values around 0.65 to values around 0.45 (see Supplementary Fig. 1). This behaviour is consistent with previous findings in experiments with humans playing a PD26. Filled circles in Fig. 1 show the probability of cooperation—that is, average fraction of cooperative actions—over the last 15 rounds for the seven groups considered (results averaging over all rounds are qualitatively similar, cf. Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, the horizontal line represents the observed value for the control group. It is apparent that the level of cooperation in groups from 17 to 65 years old and the control is quite similar, showing values in the range of 0.4<c<0.47. In contrast, the stationary level of cooperation, c=0.34, observed in the first group—under 17 years old—is significantly (P value <10−4, binomial test, significance level 0.001, and sample size 25 times the number of subjects in each group) lower than the control group, whereas the cooperation of the last group—over 65 years old—is significantly higher, c=0.55 (P value <10−4, binomial test, significance level 0.001, and sample size 25 times the number of subjects in each group). It thus follows that, in the DAU experiment, extreme age groups showed a behaviour clearly distinct from the mid-aged groups: while children between 10 and 17 years old were quite uncooperative, the elderly adopted a very cooperative behaviour (see Supplementary Table 1 for the results of the null-hypothesis binomial test).

Fraction c of cooperative actions averaged over the last 15 rounds as a function of the average age of each group. Filled circles correspond to the DAU experiment, the filled triangle to the School experiment and the filled squares stand for the average value when all children are considered. The horizontal dashed line shows the value for the control group. x axis bars cover the age range of the groups divided as follows: 10–16, 17–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65 and over 66. y axis error bars represent the s.d. of a binomial distribution over the size of the age group and the number of rounds analysed (15).

The observed behaviour for the young teenager group, impressive as it may look, must be carefully considered. There are a number of reasons why the cooperation level may be lower in this group, but prominent among those is that the people attending the DAU Festival, although it is a board games exhibition rather than a competition, may be more competitive than the average individual. The results for the control group and for the age groups from 17 through 65 years old are consistent with those reported in similar experiments27,28,29,30,31, abundant in particular for the 17–25 group. Most adult participants in the Festival were board game players themselves, so this agreement might rule out the effects of volunteer competitiveness and, in fact, it gives even more relevance to the cooperative level of the elderly players, which we will analyse later on. However, the lack of reference values for the 10–16 group, and the small number of participants we had, prompted us to replicate the experiment for this age segment, which we did with the School experiment. The results for the average cooperation level in the School experiment are also shown in Fig. 1 (filled triangles) and clearly indicate that the level of cooperation in the young teenager group is not statistically different from the control or the other groups, neither for the participants in the School experiment, nor for all participants at DAU and School pooled together (filled squares). Therefore, it can be safely concluded that the average cooperation level is the same in all the age ranges from 10 through 65 years old. As we shall discuss later on, we believe that the observed differences between both sets of children arise from their very same behaviour in front of the dilemma, although we also acknowledge that they could be rooted in the apparent higher competitiveness of the DAU children. Finally, considering that previous studies32 have found evidence on gender differences in cooperation, and given the lack of cross-generational studies on this topic, we have tested the existence of a gender dependency of the behaviour in the different age groups. However, we have not found significant differences in either cooperative levels or conditional transition probabilities between males and females in any age group.

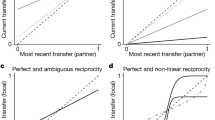

Behavioural rules

Notwithstanding, observing no significant differences in the fraction of cooperative actions among children and mid-aged individuals does not imply that all players, regardless of their ages, play following the same behavioural rules. It might well be the case that the strategies followed give rise to the same average level of cooperation, despite them being distinct. To shed more light on how people of different ages behave in social dilemmas, we analysed how the actions changed in relation to participants’ own choice in the previous round and the cooperation level they observed in their neighbourhood. This analysis has proved to be insightful in recent experiments26,29,30, in which it unveiled an unexpected dependence of the players’ actions on their own previous decision, something that had not been pointed out before. In addition to this behaviour, termed moody in the above referenced papers, conditional cooperation, that is, a dependence of the probability of cooperation on the number of partners that cooperated in the previous round was also observed. The specifics of this dependence may vary from one experiment to another: while there is often a monotonously increasing trend (approximately linear) of the probability to cooperate versus the number of cooperative neighbours of the focal player in the previous round, it is also common to find less clear dependencies.

Results from such analysis for our experiment are shown in Fig. 2 for the control (panel a) and the children groups (DAU and School, panel b). It is immediately apparent from the plot that control players clearly reproduce the moody pattern, namely, the dependence of the current decision on the previous action, while reacting to the context in a not well-defined manner. This is also the case for all age groups except young teenagers (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Remarkably, the latter group did not show any evidence of dependence on their actions on their own previous one, although they did keep their behaviour conditioned to the actions they observe, that is, they reciprocate as all other age groups. The only exception to this behaviour comes when no partner cooperated, and in this situation our findings indicate that young teenagers tend to use an alternating strategy between the two actions.

Empirical probabilities of cooperating after playing C or D, conditioned to the context (number of cooperators in the previous round) for the control sample (a) and for all children in DAU and School experiments pooled together (b), computed over all the rounds (25) of the experiment. Children show a different behaviour as compared with the rest of the groups, namely, their decisions to cooperate or defect do not seem to depend on their own actions in the previous round. The error bars represent one s.d. of a binomial distribution for a simple size equal to the number of times each context appeared.

Further evidence of the previous behaviour is provided in Fig. 3, where we show the measured conditional transition rates that a player cooperates following a cooperative action, p(C|C) or after defecting, p(C|D). These two quantities are markedly different for all groups except for the children—note that irrespective of them being from the DAU or the School experiments results are roughly the same—an observation that confirms our previous statements regarding the noticeable behavioural differences between the youths and the rest of players. We observe, first, that the behaviour of the participants aged above 17 is statistically indistinguishable from that of the control group, and, second, that the probability to cooperate following a cooperation is more than twice that following a defection. This substantial difference between the two conditional probabilities is completely absent in the case of children: they have the largest transition rate to defection after they have cooperated and the smaller permanence probability as cooperators if they did so in the previous round. Indeed, computing the average number of rounds that an individual plays as a cooperator or as a defector sequentially, one finds that children have the shortest cooperative chain, see Table 1. In addition, this happens in the two sets of players analysed, which suggests that the observed difference in the average cooperation level of the two groups of children (noticeable in Fig. 1) should arise from the initial fraction of cooperators in the first rounds—as teenagers mostly reciprocate what they observe in their neighbourhood in spite of their previous action, differences in the level of cooperation at the very first stages will propagate in a sort of feedback till the last round.

Experimentally measured probability to cooperate following a cooperation p(C|C) (filled squares) or a defection p(C|D) (filled circles) for each age group computed over all the rounds (25) of the experiment. For the young teenager group, the filled symbols correspond to the DAU experiment, and the empty symbols to the School experiment. The error bars represent the s.d. of each probability over the different age groups. The sample size for the statistical analysis is equal the number of times each context appeared. Lines correspond to control group results jointly with their s.d.

Altogether, the previous result for the youth indicates that children are inconstant in their decisions, as they are almost equally likely to repeat the last action and to change it, with defection being slightly more probable. Interestingly, this implies that children behave in a manner that may lead to cooperation breakdown or at least to its decrease, as they are not reliable partners and they may in consequence assume that their partners are not reliable as well, thus making it impossible to establish a stable cooperative scenario that ultimately could sustain long-term cooperation. Furthermore, the results in Figs 2 and 3 together discard the possibility that children play randomly. If this was the case, they would play the same way whatever the level of cooperation in their neighbourhood were, but Fig. 2b shows that they are influenced by what they observe: the larger the number of cooperators in their group, the larger the probability of playing as cooperators.

The conditional transition rates also provide hints on the larger cooperativeness of the elderly. Albeit not statistically significant (see Supplementary Table 2), the results in Fig. 3 suggest that in this group the probabilities to cooperate may be the largest in all groups. In particular, the fact that p(C|C) is very large leads to very long sequences playing as cooperators. Indeed, as seen in Table 1, the elderly show the largest average cooperative chain of all groups, more than two times the average length of the C sequences in children. In turn, the estimated conditional probabilities can be used to inform a Markov chain model that predicts the probability of permanence of a given action for at least n rounds. Such a model fits accurately the experimental observations, as seen in Supplementary Fig. 4. Furthermore, we can also estimate the total probability of cooperation: using Bayes’ theorem one has that p(D|C)p(C)=p(C|D)p(D), which, taking into account the normalization condition p(D)=1−p(C), yields for the probability of cooperation

Supplementary Fig. 5 compares the prediction to the observed result, showing again a very good agreement (see also the null-hypothesis test shown in Supplementary Table 3). This Markov chain model allows us to draw another, most relevant conclusion: one-step memory is enough to explain the actions of the players in n-player PD (in agreement with the statistical analysis presented in ref. 26). The model has also allowed to compute the profit’s distribution, see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 4.

Discussion

The findings of this study represent an important step towards a more comprehensive understanding of cooperation in humans. In particular, our experiment has a number of important implications regarding the evolution of cooperation from childhood to the elderly. The most relevant findings concern the clear differences found between children and the rest of groups and the high cooperation showed by the elderly. As for the teenagers, the observed distinct behaviour might be due to the unsophisticated development of social values in children21 with respect to adult subjects33. Admittedly, children have not fully developed cognitive and strategic abilities related to social and moral implications, such as ethics, morality, collective fairness and cooperation. They are at a stage in which they realize that rules are not rigid and are formed by mutual consent for reasons of fairness and equity and hence that these rules can be changed as the need arises. Therefore, when they meet their peers, they adopt a strategy that essentially looks for a kind of social equality, mostly reciprocating the behaviour they observe. In other words, they are not intrinsically cooperators nor defectors and implement those strategies that they believe will allow them to benefit more in return or based on the principle of what is good for others is also good for me. Interestingly, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 4, their behaviour backfires: they earn less than the other age groups, and their profit distribution is much less scattered. Conversely, mid-aged individuals and the elderly base their decisions on what people around them do and use simple heuristics, reacting to the context of cooperation they observe and attempting to keep their previous action, to some extent, to decide whether or not to cooperate.

Given the relevance of our results, it is important to discuss possible caveats about them. A first relevant point is the sample size, which admittedly is not very big, except for the young teenagers, thanks to our second experiment. During the fair at DAU we recruited as many people as we could but, particularly for the higher ages, we could not do much better because not so many senior citizens attended or were willing to take part in the experiment. However, we stress that the number of individuals we finally had is statistically significant and, in any case, like any other experimental work, it would be of the utmost importance to have this one replicated with a larger sample size in order to confirm our results. Regarding our pool of subjects, self-selection problems might also be a concern in so far as the field experiment was carried out with people attending a board game fair. As we discussed in the Introduction, we believe that this influence is compensated in part by the fact that people do not spontaneously volunteer to take part in our experiment, and we did have to persuade them to come in, often laboriously.

Another important point we have to consider relates to possible cohort effects, as they can affect developmental inferences as the ones we are drawing here. It is clear that people above 65 have experienced very different environments than people below 18. In Spain, the major change in recent times happened in the years 1975–1981, that is, during the transition from Franco's dictatorship to a democratic state34. It is not unreasonable to expect that, due to such a remarkable event, differences between people above and below 40 years arise; notwithstanding, we do not observe anything noticeable in that range of age. Cohort effects may arise also from different education systems. Unfortunately, Spain has had seven education laws and programmes in the last 30 years, so it is very difficult to grasp what the effects of this can be. In any event, the fact that there is not much difference in most of the affected range suggests that cohort effects arising from this cause are not very important. Generally speaking, we do not believe that cohort effects are affecting our results much, although we cannot possibly exclude them.

On the other hand, our key finding, the volatile behaviour observed in young teenagers, has been checked with the School experiment, in which there is no self-selection beyond possible socioeconomic effects. We do not have data to study those in our sample; however, semi-private schools in Spain such as Jesuïtes Casp are neither exclusive nor prohibitively expensive, and their students come from a wide range of middle class families, with only the poor (the School itself, jointly with parents has a collective fund for those families with financial problems) or the very rich excluded. The relative size of the rewards compared with the typical income of the different age groups could also play a role here, something that could be controlled by adjusting the reward size. However, as discussed in ref. 25, estimating income is very difficult when dealing with such a wide age range, and therefore we decided to stick to the principle of using the same set-up for all subjects. In any event, experimental results9,35 on trust games suggest that income effects are not very important (see also ref. 18; see ref. 36 for evidence of socioeconomic influence on younger children behaviour in a dictator game). Therefore, while, as we have just seen, there is room for alternative explanations of our results other than particularities of young teenagers, we believe that none of them is very likely to affect our findings significantly. The general agreement of our results with those of Charness and Villeval24 reinforces this conclusion.

Finally, a last possible caveat relates to our choice of school for the second experiment. Being run by the Jesuit order, it is in principle a religious (Catholic) school, and it has been argued (see, for example, refs 37, 38) that religious people are more cooperative. Two comments are in order in this regard. On one hand, at first-year ESO classes (children in their first year in high school) there are students of chinese origin, Muslims, Christians and, in general, believers and non-believers. Among teachers, there are also agnostic and atheist ones. School teachers intend to transmit them the idea that being good people has nothing to do with any specific religion. Not all students take Christian religion classes, neither are they mandatory; the only mandatory subject is a general one on religions, including even pre-religion beliefs. There are three Catholic masses yearly, where attendance is not mandatory for students or teachers, and where the priest makes an effort to speak for a general audience, even for atheists, focusing on common values. In addition, a poll made among the students’ parents makes it clear that the religious character of the school is not at all the main motivation for parents to choose it, confirming that there is not a special religiosity among the school attendance. Finally, in terms of family situations, this general population shows also in the fact that the school has students who live in all types of family environments, from the traditional ones to single parenthood, homosexual parenthood, divorced parents, and so on. Given this profile, it is not to be expected that our subjects are specially religious, although, as we have already clarified, even then their behaviour is exactly the same as we observed in DAU, leaving aside their slightly higher level of cooperation. On the other hand, assuming that indeed the religious character of the school explains the larger cooperativeness of the subjects in our second experiment, it is important to realize that this does not affect our main conclusion, namely their reciprocal behaviour, which is equally observed in both samples. Therefore, we are confident that our choice of school does not exert any influence on our results and conclusions.

Ultimately, our conclusions aligns with previous claims about the existence of a developmental transition in humans over time regarding empathy39 and quantitatively shows that the same shift takes place when humans are faced with social dilemmas, with a strategic change from a response to others’ actions to a more sophisticated moody (also prosocial) conditional behaviour. This finding, obtained by having subjects in a very wide range of ages participating in the same experiment, adds to observations of how altruistic or reciprocal behaviour develops in early childhood22,23. It thus seems possible that, as cooperative behaviour increases with age below 10 years, most likely due to the development of a theory of mind, the same theory of mind might give rise to a period in life in which children’s behaviour is characterized by their flexibility and ability to compromise and change rules as required. This hypothesis could also be related to the transition in trust and trustworthiness observed by Sutton and Kocher25 (see also ref. 40) and to the observed behaviour of children 6- to 12-years old in public goods and dictator experiments41, very different from that of older children and adults as they increase in later rounds of the experiment. The decrease in spitefulness in the same age range42 and the increasing inequality acceptance43 are further hints about such a key developmental transition.

Moreover, our results imply that mechanisms such as reputation and reciprocity, that are based on social perception, might be universal for humans, that is, they are not relative to the age of the individuals. However, their impact on the long-term stability of cooperation might be hindered by the inconstant behaviour in the case of children. At the same time, the large age range in which individuals exhibit similar behaviour allows to generalize observations with the usual experimental subjects. Thus, recent experiments showing that population structure do not support human cooperation in PDs29,30 should indeed be reproducible with subjects aged 17 through 65 years. The inconstant behaviour of young teenagers would also lead to the lack of cooperation in a network setting, albeit for different reasons.

Our results on the two age groups that behave differently have several policy implications. First, they suggest that, on the side of teenagers, specific strategies should be developed to promote a transition to a more persistent prosocial behaviour and to help them understand the need for some perseverance. Second, the susceptibility of children’s behaviour to what they see in their environment regardless of their own previous choices points to the fact that their future moral and strategic thinking could be conditioned to the education they have received. Finally, as suggested previously, fostering the participation of older individuals in the key social decisions or collective negotiations33 and keeping them longer in the workforce24 may be judicious procedures.

Methods

Ethics statement

All participants in the experiments reported in the manuscript signed an informed consent to participate. Besides, their anonymity was always preserved (in agreement with the Spanish Law for Personal Data Protection) by assigning them randomly a username that would identify them in the system. No association was ever made between their real names and the results. As it is standard in socioeconomic experiments, no ethical concerns are involved other than preserving the anonymity of participants. This procedure was checked and approved by the Viceprovost of Research of Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, the institution responsible for the funding for the experiment.

Experiment at DAU

The experiment was carried out with 168 volunteers selected from the attendants to DAU Barcelona Festival 2012 (first Board Game Fair of Barcelona, December 15 and 16). During the recruitment process, the experiment was referred to as a social experiment and nobody knew in advance what the experiment was about. Following the call for participation, we selected the 168 volunteers regarding age distribution criteria, with 82 males and 86 females representing the 48.81% and 51.19% of the total number of players, respectively. In order to satisfy ethical procedures, all personal data about the participants were anonymized and treated as confidential.

For every age range, and for the control treatment in which people played together irrespectively of their ages, there were six groups, except for the 17–25 range (five groups), the 56–64 range (three groups) and the over 66 range (four groups). Specifically, the volunteers’ set was divided into 42 subsets of four players according to the age distribution shown in Table 1. Control subsets constitute samples with a heterogeneous distribution of ages. Each subset of four volunteers made up a game, that is, every player had partners of his own age range (except in the control subsets) playing everyone against everyone.

All the volunteers played via a web interface specifically created for the experiment (see below) that was accessible through the computers available in the room. At least three researchers supervised the experiment in the room (which had a maximum capacity of 12 players), preventing any interaction among the volunteers. They were not allowed to talk or signal in any way. To further guarantee that potential interactions among players seating next to each other in the room do not influence the results of the experiment, the assignment of players to the different computers of the room was completely random. Hence, physical neighbours do not necessarily correspond with game partners. In addition, as described below, the colours used to code the two available actions of the game were also selected randomly, further decreasing the likelihood that neighbouring participants could influence each other.

Volunteers played a 2 × 2 PD game with each of their three neighbours, choosing the same action, either to cooperate (C) or to defect (D), for all opponents. The experiment was conducted using a slightly modified version of a software that was previously used in another, although larger, experiment30. Volunteers were allowed to choose language between Spanish or Catalan. Upon accessing the software, participants entered the directions for the experiment (detailed information is provided in the Supplementary Information, see also Supplementary Figs 7–9). When every participant of the group finished reading, the experiment begun, lasting for 25 rounds (participants were not aware of the number of rounds). After completing the experiment, participants were asked to fill a short questionnaire and then proceed to a separate part of the room where they received their payments. Volunteers under the legal age played the game by themselves while their guardians waited outside the room and received their payments with the approval and surveillance of their guardians. The overall average payment was 15.12 euros including a 5 euro show-up fee. Total earnings in the experiment ranged from 3.80 to 27.95 euros.

Experiment at jesuïtes

Jesuïtes Casp is located in the city centre of Barcelona. Jesuïtes is part of a school network of seven semi-private centres, most of them located in neighbourhoods of the city of Barcelona. Jesuïtes Casp students have a very diverse profile: it is a large school with about 1,200 students from 6 to 18 years old. Each grade has five class groups.

The experimental set-up followed the same rules as in the case of the experiment at DAU. The same web interface was used and an identical game was played. The experiment was performed on 4 March 2014. However, volunteers participated in a different way. On the basis of the DAU results, we decided to focus on a large group of teenagers between 12 and 13 years old. Young teenagers were from first year of ESO (Compulsory Secondary School) and from two different class groups (ESO 1-A and ESO 1-E). The teenagers only knew in advance that they were going to participate in a scientific experiment during a one hour class but they were not aware of any detail about the specifics of the experiment. The students’ parents were informed of the participation of their children in the experiment and explicitly authorized it. This hour class typically divides these two classes of 26 and 27 pupils, into two different subgroups; in this way, we had groups of 14 and 13 teenagers in four different rooms and split in a random way. Note that, as we played a four-people game, one student did not fit in any group and was set to play against computer robots without informing him in order to avoid leaving any of them out; however, the corresponding data have been ignored in the analysis. They did not know who their partners were, and we made sure that each player in each game was placed in a different room. In each room, one member of the research team and one teacher supervised the evolution of the experiment. The experiment was carried out with 27 males and 26 females representing 51% and 49% of the total number of volunteers, respectively. The average profit for each participant was 14.89 euros. Total earnings ranged from 9.25 euros to 19.45 euros and volunteers were informed about their own profit right after finishing the experiment. Payments were issued in the form of checks valid at a bookstore, which also sells school materials and educational toys, located at 5-min walking distance from Jesuïtes Casp. The checks were delivered to volunteers by the school teachers a couple of weeks after the experiment when parent’s signatures in check receipt were collected.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Gutiérrez-Roig, M. et al. Transition from reciprocal cooperation to persistent behaviour in social dilemmas at the end of adolescence. Nat. Commun. 5:4362 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5362 (2014).

References

Darwin, C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex Murray (1871).

Kollock, P. Social dilemmas: the anatomy of cooperation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 24, 183–214 (1998).

Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation Basic Books (1984).

Hammerstein P. (ed)Genetic and Cultural Evolution of Cooperation MIT Press (2003).

Kappeler P. M., van Schaik C. P. (eds))Cooperation in Primates and Humans: Mechanisms and Evolution Springer Verlag (2006).

Melis, A. P. How is human cooperation different? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2663–2674 (2010).

Axelrod, R. & Hamilton, W. D. The evolution of cooperation. Science 211, 1390–1396 (1981).

Rapoport, A. & Chammah, A. M. Prisoner’s Dilemma University of Michigan Press (1965).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. The nature of human altruism. Nature 425, 785–791 (2003).

Nowak, M. A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314, 1560–1563 (2006).

Hamilton, W. D. The genetical evolution of social behaviour I. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1–16 (1964).

Hamilton, W. D. The genetical evolution of social behaviour II. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 17–52 (1964).

Trivers, R. L. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–57 (1971).

Nowak, M. A. & Sigmund, K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature 393, 573–577 (1998).

Fletcher, J. A. & Doebeli, M. A simple and general explanation for the evolution of altruism. Proc. R. Soc. London B 276, 13–19 (2009).

Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene Oxford University Press (1976).

Nowak, M. A. & May, R. M. Evolutionary games and spatial chaos. Nature 359, 826–829 (1992).

Camerer, C. F. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction Princeton University Press (2003).

Naef, M., Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., Schupp, J. & Wagner, G. Decomposing Trust: Explaining National and Ethnical Trust Differences, Working Paper, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich (2008).

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D. & Sunde, U. The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. Rev. Econ. Studies 79, 645–677 (2012).

Eisenberg, N. & Fabes, R. A. inHandbook of Child Psychology, Social, Emotional, and Personality Development 5th edn Vol. 3, (eds Damon W., Eisenberg N. 701178 (Wiley (1998).

Fehr, E., Bernhard, H. & Rockenbach, B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature 54, 1079–1084 (2008).

House, B., Henrich, J., Sarnecka, B. & Silk, J. B. The development of contingent reciprocity in children. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 86–93 (2013).

Charness, G. & Villeval, M.-C. Cooperation and competition in intergenerational experiments in the field and the laboratory. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 956–978 (2009).

Sutter, M. & Kocher, M. G. Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games Econ. Behav. 59, 364–382 (2007).

Grujic, J., Eke, B., Cabrales, A., Cuesta, J. A. & Sánchez, A. Three is a crowd in iterated prisoner’s dilemmas: experimental evidence on reciprocal behavior. Sci. Rep. 2, 638 (2012).

Ledyard, J. O. inHandbook of Experimental Economics (eds Kagel J., Roth A. 111–114Princeton University Press (1995).

Traulsen, A., Semmann, D., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J. & Milinski, M. Human strategy updating in evolutionary games. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2962–2966 (2010).

Grujic, J., Fosco, C., Araujo, L., Cuesta, J. A. & Sánchez, A. Social experiments in the mesoscale: humans playing a spatial prisoner’s dilemma. PLoS ONE 5, e13749 (2010).

Gracia-Lázaro, C. et al. Heterogeneous networks do not promote cooperation when humans play a prisoner’s dilemma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12846–12947 (2012).

Grujic, J., Röhl, T., Semmann, D., Milinski, M. & Traulsen, A. Consistent strategy updating in spatial and non-spatial behavioral experiments does not promote cooperation in social networks. PLoS ONE 7, e47718 (2012).

Molina, J. A. et al. Gender differences in cooperation: experimental evidence on high school students. PLoS ONE 8, e83700 (2013).

Grossmann, I. et al. Reasoning about social conflicts improves into old age. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17246–17250 (2010).

Tusell, J. Spain: From Dictatorship to Democracy, 1939 to the Present (A History of Spain) Wiley-Blackwell (2007).

Bellemare, C. & Krüger, S. On representative social capital. Eur. Econ. Rev. 51, 183–202 (2007).

Benenson, J. F., Pascoe, J. & Radmore, N. Children's altruistic behavior in the dictator game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 168–175 (2007).

Shariff, A. F. & Norenzayan, A. God is watching you: Priming God concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous economic game. Psychol. Sci. 18, 803–809 (2007).

Rand, D. G. et al. Religious motivations for cooperation: an experimental investigation using explicit primes. Religion Brain Behav. 4, 31–48 (2014).

Hoffman, M. L. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice Cambridge University Press (2000).

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., von Rosenbladt, B., Schupp, J. & Wagner, G. G. A nationwide laboratory. Examining trust and trustworthiness by integrating behavioral experiments into representative surveys. Working paper 141. Institute for Empirical Research in Economics. University of Zurich.

Harbaugh, W. T. & Krause, K. Children’s altruism in public good and dictator experiments. Econ. Inquiry 38, 95–109 (2000).

Fehr, E., Rützler, D. & Sutter, M. The Development of Egalitarianism, Altruism, Spite and Parochialism in Childhood and Adolescence. IZA Discussion paper No. 5530 (2011).

Almas, I., Cappelen, A. W., Sorensen, E. O. & Tungodden, B. Fairness and the Development of Inequality Acceptance. Science 328, 1176–1178 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participation of 221 anonymous volunteers who have made this research possible. We are indebted to Barcelona Lab programme (especially to Nadala Fernández, Fran Iglesias and Pedro Lorente) promoted by the Direction of Creativity and Innovation from the Barcelona City Council led by Inés Garriga for their help and support setting up the experiment at the DAU Barcelona Festival at Fabra i Coats to the director of the DAU (Oriol Comas) for giving us the opportunity to make the experiment, and also to BIFI people for programming. We are also indebted to Jesuïtes Casp school and specially to teachers Pau Laball and Sandro Maccarrone for organizing and allowing us to perform the experiment at their centre. This work was supported in part by MINECO (Spain) through grants PRODIEVO, FIS2011-25167 and FIS2009-09689, by Comunidad de Madrid (Spain) through grant MODELICO, by Comunidad de Aragón (Spain) through a grant to the group FENOL, by Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain) through grant Complexity Lab Barcelona (under contract 2014 SGR 608), by the EU FET Proactive project MULTIPLEX (contract no. 317532), by Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, and by Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología (FECYT) through the Barcelona Citizen Science Office project of the Barcelona Lab programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.G.-L.,Y.M., J.P. and A.S. designed research, M.G.-R., C.G.-L.,Y.M., J.P. and A.S. performed research and wrote the paper; M.G.-R., C.G.-L. and J.P. analysed the data, and M.G.-R. and J.P. proposed and studied the theoretical model. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-10, Supplementary Tables 1-5, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Reference (PDF 651 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-Roig, M., Gracia-Lázaro, C., Perelló, J. et al. Transition from reciprocal cooperation to persistent behaviour in social dilemmas at the end of adolescence. Nat Commun 5, 4362 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5362

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5362

This article is cited by

-

Multistability, intermittency, and hybrid transitions in social contagion models on hypergraphs

Nature Communications (2023)

-

On the robustness of gender differences in economic behavior

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Gender-based pairings influence cooperative expectations and behaviours

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Strategically influencing an uncertain future

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

The influence of heterogeneous learning ability on the evolution of cooperation

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.