Abstract

Tropical south-western Pacific temperatures are of vital importance to the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), but the role of sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the growth of the GBR since the Last Glacial Maximum remains largely unknown. Here we present records of Sr/Ca and δ18O for Last Glacial Maximum and deglacial corals that show a considerably steeper meridional SST gradient than the present day in the central GBR. We find a 1–2 °C larger temperature decrease between 17° and 20°S about 20,000 to 13,000 years ago. The result is best explained by the northward expansion of cooler subtropical waters due to a weakening of the South Pacific gyre and East Australian Current. Our findings indicate that the GBR experienced substantial meridional temperature change during the last deglaciation, and serve to explain anomalous deglacial drying of northeastern Australia. Overall, the GBR developed through significant SST change and may be more resilient than previously thought.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sea surface temperature (SST) gradients in the south-western tropical Pacific control the extent of the Western Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP, SST >28 °C), the position and intensity of the Australian summer monsoon and, consequently, hydrological changes on the adjacent continent1,2. This region hosts the world’s largest extant coral reef, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) World Heritage Area, with its unique ecosystem that has evolved over hundreds of thousands of years, apparently in response to major environmental perturbations3. The SST rise from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the present is well constrained in the equatorial Pacific Ocean4,5,6,7, but is relatively unknown for the unique GBR region. A previous study suggested regional SST changes of ~1.5 °C or less during the late Pleistocene8, questioning warming SST as an explanation for the rise of the GBR9. However, this result is inconsistent with SST reconstructions for the southeastern Coral Sea10 and the WPWP7 that indicate a ~3 °C cooling during the LGM. Clearly, a better understanding of the temperature history of the GBR ecosystem since the LGM is essential in order to establish a baseline against which to judge the potential response of this region to future climate change.

Here we investigate the Sr/Ca and δ18O environmental proxies in precisely U-Th dated fossil shallow-water corals drilled by Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 325 along the shelf edge seaward of the modern GBR11 to reconstruct the meridional temperature gradient since the LGM (Fig. 1). Sr/Ca variations in aragonitic coral skeletons are a proxy for SST variability12,13. However, significant differences in mean Sr/Ca values among corals living on the same reef, and glacial-interglacial changes in seawater Sr/Ca, have hampered the reconstruction of mean tropical SSTs over the last deglaciation14,15,16,17,18. We circumvent these issues by comparing geochemical averages obtained for a large number of fossil corals from two sites in the GBR. Our premise is that corals from both sites are affected similarly by between-colony offsets, and changes in seawater Sr/Ca, thus allowing us to reconstruct relative changes in the meridional temperature gradient along the GBR. Coral δ18O, a proxy that reflects both temperature and seawater δ18O variations, and which is affected differently by between-colony offsets in mean coral δ18O (refs 19, 20) and glacial-interglacial changes in seawater δ18O, is used to support our reconstruction14,21,22. Contrary to coral Sr/Ca, coral δ18O can be influenced by site-specific changes in seawater δ18O. We show that the meridional SST gradient in the GBR region was considerably steeper than today during the LGM and last deglaciation, which is best explained by northward expansion of cooler subtropical waters, owing to weakening of the South Pacific subtropical gyre and East Australian Current (EAC). Our findings indicate that the GBR experienced substantial and regionally differing temperature change during the last deglaciation, much larger temperature changes than previously recognized. Furthermore, our findings suggest a northward contraction of the WPWP during the LGM and last deglaciation, and serve to explain anomalous drying of northeastern Australia at that time.

Locations of Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 325 drilling sites at Noggin Pass (NOG) and Hydrographer’s Passage (HYD) in the central Great Barrier Reef11 are superimposed on annual mean sea surface temperature35 (SST) and surface ocean circulation patterns in the study area39 (SEC, South Equatorial Current; EAC, East Australian Current; TF, Tasman Front). For reference, the modern coral site at Heron Island (HER) in the southern Great Barrier Reef and sediment core MD97-2125 in the southeastern Coral Sea10 are shown. The Coral Sea is the region off the northeast coast of Australia that is bounded by New Guinea to the north and several smaller islands in the east. The Western Pacific Warm Pool is defined as the region where annual mean SST is greater than 28 °C (ref. 62).

Results

Coral preservation and ages

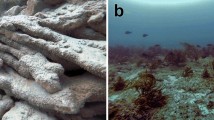

The drill cores of IODP Expedition 325 intersected massive and robust branching/columnar Isopora palifera/cuneata colonies, which are common in shallow-water (0–10 m), high-energy reef crest environments23,24. Fossil Isopora corals were recovered at Noggin Pass (NOG, 17.1°S) and Hydrographer’s Passage (HYD, 19.7°S) in the central GBR11 (Fig. 1). The corals were screened for possible diagenetic alteration of their skeletons using X-radiography, powder X-ray diffraction, thin-section petrography and Mg/Ca screening, and are well preserved (Methods and Supplementary Figs 1–4). U-Th dating yielded coral ages spanning 25 to 12 thousand years before the present (kyr BP; ‘present’ is defined as AD 1950) (Methods and Supplementary Table 1). All coral specimens were analysed for Sr/Ca, δ18O, Mg/Ca and δ13C along their major growth orientation (Methods; Supplementary Figs 1, 3 and 4; Supplementary Table 2). A total of 881 samples were analysed at subseasonal resolution in 7 fossil Isopora corals (Supplementary Fig. 3). An additional 18 fossil and 13 modern Isopora were analysed for bulk geochemical composition, as the major aim of the study is the reconstruction of mean SST changes from geochemical averages of corals.

Coral-based SST reconstruction

The performance of Sr/Ca and δ18O in Isopora corals was assessed using modern colonies from Heron Island (HER, 23.4°S) in the southern GBR (Fig. 1), which provides a modern analogue with relatively cool SSTs such as those experienced by last deglacial central GBR corals. The modern corals reveal between-colony offsets in mean Sr/Ca and δ18O that are equivalent to ~1–2 °C (Fig. 2) and similar to those seen in Porites corals18,25 (Supplementary Note 1). We note that the modern Isopora corals represent a range of shallow-water habitats on the reef, comparable to the environment represented by the fossil corals. Thus, the between-colony offsets reflect the combined effects of differences in water depth, location on the reef and different time intervals26,27,28. Furthermore, initial comparison of bulk samples from modern Isopora corals from Papua New Guinea, and the central and southern GBR (spanning a mean SST range of ~4.5 °C), indicates similar Sr/Ca-SST and δ18O-SST relationships to those for Porites, supporting our use of the better-constrained mean relationships established for Porites (Methods and Supplementary Note 2).

(a) Western Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP) sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly7 (left y axis) and southeastern Coral Sea SST10 (right y axis) reconstructed from planktonic foraminiferal Mg/Ca. Modern annual mean WPWP SST is >4 °C warmer than SST in the southeastern Coral Sea35. (b) Mean Sr/Ca of individual Isopora palifera/cuneata corals from Noggin Pass (NOG) and Hydrographer’s Passage (HYD), central Great Barrier Reef (GBR), and Heron Island (HER), southern GBR (approximate latitude indicated). Weighted least-squares regression lines are shown for NOG and HYD, utilizing data variances as weights. HYD coral Sr/Ca is significantly different from NOG coral Sr/Ca (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 5). The coral-based SST anomalies are not adjusted for changes in seawater Sr/Ca, and thus provide upper estimates of the magnitude of cooling. However, the effects of seawater Sr/Ca changes are similar at both sites, so the reconstructed SST differences between sites are not affected. For reference, the fossil coral-based Sr/Ca-SST anomalies are plotted relative to average Sr/Ca at HER (dashed green line). Modern mean SST35 at NOG (26.6 °C) and HYD (26.0 °C) is shown relative to SST at HER (24.5 °C) and scaled using the mean coral Sr/Ca-SST relationships of −0.084 mmol mol−1 per °C (ref. 34) (solid red and blue lines) and −0.140 mmol mol−1 per °C (ref. 32) (dashed red and blue lines). (c) As in b, but for mean coral δ18O corrected for the influence of changes in ice volume using a global compilation of benthic foraminifer δ18O records37 (for uncorrected coral δ18O see Supplementary Fig. 8). The resulting coral δ18O-SST anomalies are shown relative to average δ18O at HER (dashed green line) using the average of three mean coral δ18O-SST relationships (−0.22‰ per °C, refs 32, 33, 34). The larger cooling inferred from coral δ18O compared with Sr/Ca suggests a positive seawater δ18O anomaly. Modern mean SST35 at NOG and HYD is shown relative to HER (solid red and blue lines). The grey shading indicates the timing of the Last Glacial Maximum63,64 (LGM).

The fossil coral Sr/Ca-SSTs show the deglacial warming trend for the interval ~21 to ~12 kyr BP (Fig. 2). Furthermore, they show that the deglacial SST rise began no later than 19 kyr BP, consistent with the ~20 kyr BP onset of the deglacial SST rise in the southeastern Coral Sea (MD97-2125; 161°44′E, 22°34′S)10 (Figs 1 and 2). Importantly, SSTs in the GBR region do not show cooling associated with the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas (YD) event29 (~12.9 to ~11.7 kyr BP). This finding is in contrast to coral Sr/Ca evidence for YD cooling at Vanuatu16 and Tahiti17, located further east, and at the same latitude as the GBR, in the western and central South Pacific. This highlights the regional complexity of the response of low-latitude climates to YD cooling in the North Atlantic region. The relatively warm SSTs in the GBR during the YD are consistent with an Antarctic-type pattern of deglacial warming as observed further to the south30,31, as well as with the near-continuous deglacial warming observed throughout most of the WPWP to the north7.

Direct application of modern coral Sr/Ca-SST relationships32,33,34 (Methods) would yield estimates of LGM (~21 kyr BP) SSTs 4–6 °C cooler than today at NOG (17°S), and late LGM (~19 kyr BP) SSTs 6–8 °C cooler than today at HYD (20°S). These estimates use modern Isopora corals from HER (23°S) as the modern benchmark and take into account the modern SST difference between HER and the central GBR (Figs 1 and 2). The modern annual mean SSTs are 24.5 °C at HER, and 26.0 °C (HYD) and 26.6 °C (NOG) at the central GBR sites (ref. 35). However, the estimates of LGM SSTs are uncorrected for changes in seawater Sr/Ca (owing to large uncertainties in this factor15,17,18) and are therefore likely to provide upper estimates of the magnitude of cooling. To further constrain the absolute magnitude of SST change, we consider 21.5 °C as the lower limit for coral growth, this temperature being the annual mean SST experienced by modern Isopora corals at Lord Howe Island (159.1°E, 31.5°S), the southernmost Pacific reef35,36. This ecological constraint implies potential maximum cooling of ~5 °C at NOG and ~4.5 °C at HYD, which is slightly less than the uncorrected coral Sr/Ca-SST estimates, and broadly in line with our understanding of glacial-interglacial changes in seawater Sr/Ca (ref. 15). Interestingly, if coral δ18O is used on its own to estimate glacial SSTs (correcting for glacial-interglacial changes in seawater δ18O (ref. 37) but not for regional seawater δ18O changes), we find LGM SSTs ~7 °C cooler than today at NOG (17°S) and ~9 °C cooler during the late LGM (~19 kyr BP) at HYD (20°S). Taken together, the apparent 2–4 °C difference between the coral Sr/Ca- and ecologically-based estimate (4–5 °C) and δ18O-based estimate (7–9 °C) of LGM SST cooling suggests a positive δ18O anomaly (0.4–0.8‰) for GBR surface waters. This anomaly would be consistent with reduced regional precipitation minus evaporation balance at the time, although other changes in the hydrological cycle and surface ocean circulation may also contribute.

Coral-based SST gradient reconstruction

Our most striking finding is that the mean Sr/Ca values for the 24 fossil Isopora corals with ages spanning ~20 to ~13 kyr BP for the southern (HYD) and northern sites (NOG) form two separate groups (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 2). Regression analysis indicates that the HYD coral Sr/Ca is significantly higher than the NOG coral Sr/Ca (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, the significance of the difference between the HYD and NOG palaeo-SSTs is verified by regression analysis of the coral δ18O values for the two sites (Fig. 2). Importantly, our analysis of relative changes in the meridional SST gradient is not biased by glacial-interglacial changes in seawater Sr/Ca and δ18O because the effects would be essentially the same at both sites. The difference in mean SST changes given by the HYD and NOG coral Sr/Ca and δ18O indicates that the southern site was on average 2–3 °C cooler32,33,34 relative to the northern site from ~20 to ~13 kyr BP (Fig. 2). Given the relatively small meridional difference in SST today (<0.6 °C, ref. 35; Supplementary Discussion) between the two sites (Fig. 1), our results indicate a steeper meridional SST gradient along the central GBR between 17° and 20°S throughout most of the LGM and deglaciation.

Discussion

Today, meridional SST gradients such as those along the GBR during the LGM and deglaciation are only observed south of ~30°S on the eastern Australian margin35 (Fig. 1). At this latitude, the EAC, which transports warm tropical waters southward along the eastern Australian coast, separates from the continent to form the Tasman Front38,39. Therefore, the steeper LGM and deglacial SST gradient may be due to EAC weakening and northward expansion of cooler subtropical waters. Furthermore, the relatively high δ18O of central GBR waters during the LGM, shown by the coral records, supports the interpretation of northward expansion of high-salinity subtropical waters (Supplementary Fig. 6). The results are consistent with studies of planktonic foraminifer assemblages40 and δ18O (ref. 38), indicating northward displacement of subtropical waters, the EAC separation and the Tasman Front to ~25°S during the LGM40 and deglaciation38. However, our results indicate that cooler waters were displaced as far north as 20° to 17°S in the central GBR, and that the steeper meridional SST gradient at this latitude was a robust feature of the LGM and deglaciation. The coral Sr/Ca data indicate that the SST gradient decreased significantly from the LGM towards the late deglaciation (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 5), due to greater warming at the southern site compared with the northern site.

The available palaeoclimate records indicate that the steeper meridional SST gradient in the central GBR does not reflect a regionally steeper meridional SST gradient in the south-western tropical Pacific because the south-western tropical Pacific meridional SST gradient was actually weaker than today during the last deglaciation. The deglacial SST rise in the southeastern Coral Sea (MD97-2125; 161°44′E, 22°34′S) started earlier (~20 kyr BP) and reached modern SST as early as ~17 kyr BP (ref. 10), whereas warming in the WPWP commenced at ~17.5 kyr BP and reached modern SST as late as ~12 kyr BP (ref. 7) (Fig. 2). Both regions cooled by similar amounts during the LGM (~3 °C) (refs 7, 10) and today the WPWP is >4 °C warmer than the southeastern Coral Sea35 (Figs 1 and 2), so the earlier start of the deglacial warming in the southeastern Coral Sea, relative to warming in the WPWP, means that the meridional SST gradient in the tropical southwest Pacific was weaker than today during the last deglaciation. This is opposite to our reconstructed steepening of the meridional SST gradient along the central GBR at that time, and is consistent with weakening of the EAC along the eastern Australian coast during the LGM and deglaciation. Furthermore, the reduction in heat transfer from low to mid-latitudes due to weakening of the EAC, which is the western boundary current of the South Pacific subtropical gyre, may have played an important role in dampening the amplitude of LGM cooling in the WPWP. Interestingly, the increase in heat transfer from low to mid-latitudes implied by EAC strengthening after ~12.7 kyr BP, suggested by the coral records, coincides with the end of the deglacial SST rise in the WPWP7. The results suggest an important role for variations in the strength of the South Pacific’s western boundary current, and changes in the transport of warm tropical waters to higher latitudes, in contributing to SST changes in the WPWP on glacial-interglacial timescales.

A steeper meridional SST gradient and cooler ocean surface off northeast Australia between ~20 and ~13 kyr BP may explain anomalously dry conditions in northeastern Australia at that time inferred from the Lynch’s Crater sediment record1,41 (145°70′E, 17°37′S). The cooler deglacial waters could have reduced the effectiveness of the southeasterlies in advecting moisture from the Coral Sea to the adjacent continent. Furthermore, these waters could have potentially restricted the southern boundary of the WPWP and southward migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone to a more northerly position, thus inhibiting development of the Australian summer monsoon. The southward displacement of subtropical waters after ~12.7 kyr BP, indicated by the coral records, was potentially accompanied by a southward shift of the southern boundary of the WPWP and the Intertropical Convergence Zone, and was probably driven by spin-up of the South Pacific subtropical gyre and corresponding strengthening of the EAC in response to deglacial warming38.

Our findings indicate that the GBR has experienced much larger SST changes—both spatially and temporally—since the LGM than previously recognized. This was especially the case in the south, owing to significant steepening of the meridional SST gradient resulting from a northward expansion of cooler subtropical waters during the LGM and deglaciation. Combined with evidence for the existence of extensive reefs along the shelf edge seaward of the modern GBR at that time11,42, our results provide new insights into the ability of coral reefs to adapt to temperature change. Most corals are well adapted to their local temperature regime, but are susceptible to thermal stress resulting in bleaching and sometimes mortality, where the mean summer maximum temperature is exceeded by >~1 °C (ref. 43). As a consequence, the absolute thermal limit for coral bleaching is strongly site dependent43, and questions remain on the timescales over which corals may adapt to temperature rise44,45. The apparent resilience of the GBR Isopora coral reef community throughout much of the last deglaciation, despite substantial increases in SST from the LGM condition, demonstrates that adaption occurred over a few thousand years or less. This apparent resilience further suggests that, considering temperature alone, southward expansion of this robust reef crest community could be an important response to future climate warming.

Methods

Coral samples

Fossil Isopora palifera/cuneata corals were recovered in 2010 by IODP Expedition 325 off the central Great Barrier Reef11 (GBR). Corals were recovered at depths between 56 and 126 m below modern sea level at Noggin Pass (NOG; 146.6°E, 17.1°S; IODP sites M0053 and M0057) and Hydrographer’s Passage (HYD; 150.3°E, 19.7°S; IODP sites M0031, M0033, M0035, M0036 and M0039) using the mission-specific platform ‘Greatship Maya’. Modern Isopora palifera/cuneata corals were collected at Heron Island (HER; 151.9°E, 23.4°S) in the southern GBR from 1974 to 1979 at depths between 0 and 14 m.

Screening for diagenesis

The aragonitic skeletons of all fossil corals were analysed by powder X-ray diffraction and X-radiography, indicating ≤1.5% calcite (Supplementary Table 2) and demonstrating that skeletal areas of obvious diagenetic alteration were not analysed (Supplementary Fig. 1). Selected fossil corals were also investigated using petrographic thin sections and showed excellent preservation of primary porosity, with no evidence for significant amounts of secondary aragonite or calcite cements (Supplementary Fig. 2). Skeletal Mg/Ca ratios indicate the absence of significant amounts of high-Mg calcite and secondary aragonite cements along the analysed transects (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). Seven corals were analysed at 0.3-mm resolution for element/Ca and stable isotope ratios. No influence of subtle diagenetic alteration was detected on this spatial scale. The reported mean geochemical values are very similar to those for corals of similar age analysed for bulk composition.

U-Th dating

The chronology of the fossil corals was determined by U-Th dating carried out using different methods at three laboratories: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Australian National University (ANU) and University of Oxford (OX). The originating laboratories are identified alongside the data in Supplementary Table 1. U-Th ages are reported in kyr before the present relative to AD 1950. Interlaboratory replicate age determinations for a single specimen agree to within 100 years, which is similar to the intra-coral variability observed in some specimens measured using the high-precision (WHOI) method. The corals used in this study have initial 234U/238U activity ratios between 1.140 and 1.150, which are close to the modern seawater composition giving additional confidence in the chronology. Briefly the methods are:

At WHOI, U and Th isotopes are measured by MC-ICP-MS in static mode with all isotopes in Faraday collectors46. Large ~5-g subsamples of coral are dissolved and spiked with a mixed 233U:236U:229Th tracer, optimized for deglacial age samples and co-precipitated with Fe. To determine the 230Th/238U, purified U and Th fractions are recombined such that U and Th are measured together at isotope ratios that can be closely matched to bracketing standards. The 234U/238U is similarly determined statically in Faraday collectors but on an unspiked aliquot.

At ANU, U and Th isotopes are measured by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (ref. 47). Approximately 1–2 g of coral samples are spiked with a mixed 233U: 229Th tracer, and U and Th are separated using U-Teva resin in a single pass. The 229-230-232Th isotopes were measured simultaneously in charge mode, in Faraday cups, using 20 pF feed-back capacitors as active electrometer elements48. U isotopes 233-234-235U are also measured in charge-collection mode while, 238U is measured using a 1010-Ohm feed-back resistor simultaneously in Faraday cups. The magnitude of the 238U low-mass tail was monitored continuously at mass 237U in charge mode. This was used to subtract the 238U tail from under 233-234-235U isotopes. Extensive measurements with an unspiked U-standard HU-1 showed that the curvature of the 238U tail remained invariant under a wide range of operating conditions, in particular, at the expected locations of the 233-236U peaks. U sample loads, on single rhenium filaments, ranged from 0.5 to 0.8 μg and the 238U beam intensity was kept between 8 × 1011 and 10 × 1011 A for several hours. At these intensities, the 1010-Ohm feed-back resistor was used to avoid response-time problems encountered with the considerably slower 1011-Ohm resistors. The instrument was calibrated with reference to a secular equilibrium standard HU-1. Comparisons with Western Australian coral samples for the last interglacial47 showed precise agreement with previous measurements.

At OX, U and Th isotopes are measured by MC-ICP-MS utilizing ion counter collectors for the minor isotope beams. Approximately 0.3 g of coral samples are dissolved and spiked with a mixed 236U:229Th tracer. U and Th are purified and measured separately: U isotopes, statically; and Th by peak hopping the 229 and 230 beams into an ion counter normalizing beam intensity between steps with either 232Th or 235U measured in Faraday collectors. Instrumental biases and relative collector efficiencies are accounted for using standard-sample bracketing using U and Th isotope standards49.

All activity ratios and ages are calculated using the half lives reported in ref. 50. Ages are presented in Supplementary Table 1 as ‘raw’, assuming all 230Th is accumulated in the coral since growth, and an age corrected for detrital 230Th. The detrital correction makes use of the measured 232Th/238U as a proxy for the amount of detrital contamination, an assumed detrital composition of crustal origin51, and an allowance for non-secular equilibrium of the contaminant (232Th/238U=1.21±0.6, 230Th/238U=1±0.25 and 234U/238U=1±0.25). All ages are calculated relative to AD 1950 for consistency.

Microsampling

All coral specimens were microsampled continuously along their major growth orientation (Supplementary Fig. 1). We note that the major growth axis of a coral colony is difficult to discern from drill cores with a diameter much smaller than the colony, and that sampling paths with respect to coral morphology may produce different geochemical variations52,53,54. We cannot completely exclude such effects but note that the majority of our massive Isopora specimens indicate uniform parallel growth of corallites, suggesting the absence of colony morphology effects on this spatial scale. Seven corals were microsampled at subseasonal resolution, by milling a trench 2.4 mm wide and 3.0 mm deep, using a sample-step increment of 0.3 mm. All other corals were sampled for bulk geochemical composition by milling a continuous trench of similar width and depth.

Geochemical and isotopic analyses

Coral element/Ca and stable isotope ratios were analysed on splits of the same sample powders at MARUM (Bremen), ANU (Canberra), LDEO (Palisades), GeoSciences (Edinburgh), AIST (Tsukuba) and AORI (Kashiwa), using ICP-OES, ICP-MS and dual-inlet stable-isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Bulk powders of fossil corals were analysed at least in triplicate. The coral reference material JCp-1 was used to correct for interlaboratory offsets55. The JCp-1 reference compositions used in this study are 8.781 mmol mol−1 for Sr/Ca, −4.75‰ for δ18O, 4.252 mmol mol−1 for Mg/Ca and −1.58‰ for δ13C. These values represent the average of >100 element/Ca and >60 δ18O and δ13C analyses of splits of JCp-1 powder that were treated like samples in the participating laboratories.

Isopora coral as an SST archive

Isopora56 has been considered a subgenus of the coral genus Acropora, but was recently elevated to genus57. Massive and robust branching/columnar Isopora palifera/cuneata corals are common in the upper 10 m of well-flushed reef crest environments23,24, providing an excellent potential archive of open-ocean SST. However, submillimetre-scale analysis of seven massive Isopora, the growth form most common in our study, did not reveal clear annual cycles in Sr/Ca and δ18O (Supplementary Fig. 3). It is possible that the complex skeletal architecture, including discontinuous filament-like structures perpendicular to the growth direction, and spatially heterogeneous calcification processes within massive Isopora corals obscure the annual cycle given that diagenesis was ruled out for these samples. We note that studies on branching Acropora corals (A. palmata, A. nobilis) did not reveal clear annual cycles in Sr/Ca and δ18O along axes of radial growth58,59, which was attributed to spatially heterogeneous calcification processes such as secondary thickening of skeletal elements58,59,60.

In the absence of definitive calibration data for massive Isopora, the average of well-established mean proxy-SST relationships for Porites corals was used to reconstruct changes in mean SST: −0.084 mmol mol−1 per °C (ref. 34), −0.089 mmol mol−1 per °C (ref. 33), −0.140 mmol mol−1 per °C (ref. 32) for coral Sr/Ca and −0.22‰ per °C (refs 32, 33, 34) for coral δ18O. The relationships for Porites are based on rescaled seasonal calibrations for studying changes in mean SST34, on calibrations derived from bulk coral values for reef settings with different average temperatures33 and on annual mean calibrations using coral time series32. Preliminary bulk calibration experiments on modern Isopora corals suggest similar Sr/Ca- and δ18O-SST relationships to the better-studied Porites genera (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Note 2). The Isopora bulk calibration slope for Sr/Ca lies closer to the seasonal Porites slope for Sr/Ca than to the bulk Porites slope. Furthermore, seasonal Sr/Ca calibration slopes similar to Porites were reported for a coral in the same family as Isopora, Acropora palmata58, and early studies found similar Sr/Ca and δ18O bulk calibration slopes for Acropora and Porites26,27.

For the fossil Isopora corals, the subseasonally resolved geochemical records and analysis of density bands in X-radiographs (subseasonally and bulk-sampled corals) indicate that each coral analysed encompasses several years of skeletal growth. On the basis of this anaylsis, there is no clear indication for systematically lower growth rates at the southern site compared with the northern site. Thus the relatively cool reconstructed SSTs at the southern site are not the result of a potential influence of lower growth rates on SST proxies.

Statistical analysis

Regression analysis was performed by applying a straight-line weighted least-squares fit (utilizing data variances as weights, 1/sigma(i)2, ref. 61) to the coral data from HYD and NOG and the difference in straight-line fit (HYD−NOG) was determined. A Monte Carlo error simulation61 was performed for the difference in straight-line fit by generating random deviations from original data points, from which simulated straight lines and simulated fit differences resulted. The s.e. of these differences (versus time) was used to generate the error envelope (Supplementary Fig. 5). Simulations (400) were performed with independent, normally distributed random deviations (s.d. equal to dating error for age simulation and equal to measurement error × inflation factor for proxy simulation). The fit residuals were used to determine the mean deviation from the fitted line (root of residual mean square). This quantity was compared with the mean proxy measurement error, which is smaller by a factor of 2 for HYD coral δ18O, smaller by a factor of 3 for NOG coral δ18O, smaller by a factor of 2 for HYD coral Sr/Ca and about the same for NOG coral Sr/Ca. Consequently, a conservative approach was chosen by artificially inflating the assumed measurement error, in order to simulate the influence of errors induced by effects such as between-colony variability. A measurement-error inflation factor of 3.0 was used to calculate the s.e. band for our difference in straight-line fit. However, the difference is still larger than zero for both coral Sr/Ca and δ18O. Therefore the HYD coral Sr/Ca is significantly different from the NOG coral Sr/Ca, and the HYD coral δ18O is significantly different from the NOG coral δ18O.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Felis, T. et al. Intensification of the meridional temperature gradient in the Great Barrier Reef following the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Commun. 5:4102 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5102 (2014).

Change history

15 June 2016

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Turney, C. S. M. et al. Climatic variability in the southwest Pacific during the last termination (20–10 kyr BP). Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 886–903 (2006).

Reeves, J. M. et al. Palaeoenvironmental change in tropical Australasia over the last 30,000 years—a synthesis by the OZ-INTIMATE group. Quat. Sci. Rev. 74, 97–114 (2013).

Alexander, I. et al. New constraints on the origin of the Australian Great Barrier Reef: results from an international project of deep coring. Geology 29, 483–486 (2001).

Lea, D. W., Pak, D. K. & Spero, H. J. Climate impact of late Quaternary equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature variations. Science 289, 1719–1724 (2000).

Stott, L., Timmermann, A. & Thunell, R. Southern hemisphere and deep-sea warming led deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise and tropical warming. Science 318, 435–438 (2007).

Koutavas, A. & Sachs, J. P. Northern timing of deglaciation in the eastern equatorial Pacific from alkenone paleothermometry. Paleoceanography 23, PA4205 (2008).

Linsley, B. K., Rosenthal, Y. & Oppo, D. W. Holocene evolution of the Indonesian throughflow and the western Pacific warm pool. Nat. Geosci. 3, 578–583 (2010).

Lawrence, K. T. & Herbert, T. D. Late Quaternary sea-surface temperatures in the western Coral Sea: implications for the growth of the Australian Great Barrier Reef. Geology 33, 677–680 (2005).

Peerdeman, F. M., Davies, P. J. & Chivas, A. R. inProceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results Vol. 133, eds McKenzie J. A., Davies P. J., Palmer-Julson A. 163–173Ocean Drilling Program (1993).

Tachikawa, K., Vidal, L., Sonzogni, C. & Bard, E. Glacial/interglacial sea surface temperature changes in the Southwest Pacific ocean over the past 360 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 1160–1170 (2009).

Webster, J. M., Yokoyama, Y. & Cotteril, C. & the Expedition 325 Scientists. Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Vol. 325, Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Management International Inc. (2011).

Beck, J. W. et al. Sea-surface temperature from coral skeletal strontium/calcium ratios. Science 257, 644–647 (1992).

Corrège, T. Sea surface temperature and salinity reconstruction from coral geochemical tracers. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 232, 408–428 (2006).

Guilderson, T. P., Fairbanks, R. G. & Rubenstone, J. L. Tropical temperature variations since 20,000 years ago: modulating interhemispheric climate change. Science 263, 663–665 (1994).

Stoll, H. M., Schrag, D. P. & Clemens, S. C. Are seawater Sr/Ca variations preserved in Quaternary foraminifera? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 3535–3547 (1999).

Corrège, T. et al. Interdecadal variation in the extent of South Pacific tropical waters during the Younger Dryas event. Nature 428, 927–929 (2004).

Asami, R. et al. Evidence for tropical South Pacific climate change during the Younger Dryas and the Bølling-Allerød from geochemical records of fossil Tahiti corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 288, 96–107 (2009).

Felis, T. et al. Pronounced interannual variability in tropical South Pacific temperatures during Heinrich Stadial 1. Nat. Commun. 3, 965 (2012).

Felis, T. et al. Increased seasonality in Middle East temperatures during the last interglacial period. Nature 429, 164–168 (2004).

Hayashi, E. et al. Growth-rate influences on coral climate proxies tested by a multiple colony culture experiment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 362, 198–206 (2013).

Tudhope, A. W. et al. Variability in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation through a glacial-interglacial cycle. Science 291, 1511–1517 (2001).

Kilbourne, K. H., Quinn, T. M. & Taylor, F. W. A fossil coral perspective on western tropical Pacific climate ~350 ka. Paleoceanography 19, PA1019 (2004).

Done, T. J. Patterns in the distribution of coral communities across the central Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 1, 95–107 (1982).

Done, T. J. inPerspectives on coral reefs ed. Barnes D. J. 107–147Australian Institute of Marine Science (1983).

Linsley, B. K., Messier, R. G. & Dunbar, R. B. Assessing between-colony oxygen isotope variability in the coral Porites lobata at Clipperton Atoll. Coral Reefs 18, 13–27 (1999).

Weber, J. N. & Woodhead, P. M. J. Temperature dependence of oxygen-18 concentration in reef coral carbonates. J. Geophys. Res. 77, 463–473 (1972).

Weber, J. N. Incorporation of strontium into reef coral skeletal carbonate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 37, 2173–2190 (1973).

Fallon, S. J., McCulloch, M. T. & Alibert, C. Examining water temperature proxies in Porites corals from the Great Barrier Reef: a cross-shelf comparison. Coral Reefs 22, 389–404 (2003).

Denton, G. H. et al. The last glacial termination. Science 328, 1652–1656 (2010).

Kaplan, M. R. et al. Glacier retreat in New Zealand during the Younger Dryas stadial. Nature 467, 194–197 (2010).

Bostock, H. C. et al. A review of the Australian–New Zealand sector of the Southern Ocean over the last 30 ka (Aus-INTIMATE project). Quat. Sci. Rev. 74, 35–57 (2013).

Felis, T. et al. Subtropical coral reveals abrupt early-twentieth-century freshening in the western North Pacific Ocean. Geology 37, 527–530 (2009).

DeLong, K. L., Quinn, T. M., Shen, C.-C. & Lin, K. A snapshot of climate variability at Tahiti at 9.5 ka using a fossil coral from IODP Expedition 310. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, Q06005 (2010).

Gagan, M. K., Dunbar, G. B. & Suzuki, A. The effect of skeletal mass accumulation in Porites on coral Sr/Ca and δ18O paleothermometry. Paleoceanography 27, PA1203 (2012).

Locarnini, R. A. et al. inWorld Ocean Atlas 2009: Temperature. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 68 Vol. 1, (ed Levitus S. 184US Government Printing Office (2010).

Veron, J. E. N. & Done, T. J. Corals and coral communities of Lord Howe Island. Aust. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 30, 203–236 (1979).

Waelbroeck, C. et al. Sea-level and deep water temperature changes derived from benthic foraminifera isotopic records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 295–305 (2002).

Bostock, H. C., Opdyke, B. N., Gagan, M. K., Kiss, A. E. & Fifield, L. K. Glacial/interglacial changes in the East Australian current. Clim. Dyn. 26, 645–659 (2006).

Hill, K. L., Rintoul, S. R., Ridgway, K. R. & Oke, P. R. Decadal changes in the South Pacific western boundary current system revealed in observations and ocean state estimates. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C01009 (2011).

Anderson, D. M., Prell, W. L. & Barratt, N. J. Estimates of sea surface temperature in the Coral Sea at the Last Glacial Maximum. Paleoceanography 4, 615–627 (1989).

Muller, J. et al. Possible evidence for wet Heinrich phases in tropical NE Australia: the Lynch’s Crater deposit. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 468–475 (2008).

Abbey, E., Webster, J. M. & Beaman, R. J. Geomorphology of submerged reefs on the shelf edge of the Great Barrier Reef: the influence of oscillating Pleistocene sea-levels. Mar. Geol. 288, 61–78 (2011).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs. Mar. Freshwater Res. 50, 839–866 (1999).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301, 929–933 (2003).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742 (2007).

O'Leary, M. J. et al. Ice sheet collapse following a prolonged period of stable sea level during the last interglacial. Nat. Geosci. 6, 796–800 (2013).

Stirling, C. H., Esat, T. M., McCulloch, M. T. & Lambeck, K. High-precision U-series dating of corals from Western Australia and implications for the timing and duration of the Last Interglacial. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 135, 115–130 (1995).

Esat, T. M. Charge collection thermal ion mass spectrometry of thorium. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 148, 159–170 (1995).

Mason, A. J. & Henderson, G. M. Correction of multi-collector-ICP-MS instrumental biases in high-precision uranium–thorium chronology. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 295, 26–35 (2010).

Cheng, H. et al. The half-lives of Uranium-234 and Thorium-230. Chem. Geol. 169, 17–33 (2000).

Taylor, S. R. & McLennan, S. M. The Continental Crust: its Composition and Evolution: an Examination of the Geochemical Record Preserved in Sedimentary Rocks 312Blackwell Scientific (1985).

McConnaughey, T. 13C and 18O isotopic disequilibrium in biological carbonates: I. Patterns. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 151–162 (1989).

Alibert, C. & McCulloch, M. T. Strontium/calcium ratios in modern Porites corals from the Great Barrier Reef as a proxy for sea surface temperature: calibration of the thermometer and monitoring of ENSO. Paleoceanography 12, 345–363 (1997).

Cohen, A. L. & Hart, S. R. The effect of colony topography on climate signals in coral skeleton. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3905–3912 (1997).

Hathorne, E. C. et al. Interlaboratory study for coral Sr/Ca and other element/Ca ratio measurements. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 3730–3750 (2013).

Studer, T. Zweite Abtheilung der Anthozoa polyactinia, welche während der Reise S. M. S. Corvette Gazelle um die Erde gesammelt wurden. Monatsber. Königlich Preussischen Akad. Wissenschaften Berlin 1878, 524–550 (1878).

Wallace, C. C., Chen, C. A., Fukami, H. & Muir, P. R. Recognition of separate genera within Acropora based on new morphological, reproductive and genetic evidence from Acropora togianensis, and elevation of the subgenus Isopora Studer, 1878 to genus (Scleractinia: Astrocoeniidae; Acroporidae). Coral Reefs 26, 231–239 (2007).

Gallup, C. D. et al. Sr/Ca-Sea surface temperature calibration in the branching Caribbean coral Acropora palmata. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L03606 (2006).

Shirai, K. et al. Minor and trace element incorporation into branching coral Acropora nobilis skeleton. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 5386–5400 (2008).

Gladfelter, E. H. Skeletal development in Acropora cervicornis: I. Patterns of calcium carbonate accretion in the axial corallite. Coral Reefs 1, 45–51 (1982).

Mudelsee, M. Climate Time Series Analysis: Classical Statistical and Bootstrap Methods 474Springer (2010).

Yan, X.-H., Ho, C.-R., Zheng, Q. & Klemas, V. Temperature and size variabilities of the Western Pacific Warm Pool. Science 258, 1643–1645 (1992).

Mix, A. C., Bard, E. & Schneider, R. Environmental processes of the ice age: land, oceans, glaciers (EPILOG). Quat. Sci. Rev. 20, 627–657 (2001).

MARGO Project Members. Constraints on the magnitude and patterns of ocean cooling at the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 2, 127–132 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research used samples provided by IODP, drilled on a mission-specific platform expedition (Expedition 325—Great Barrier Reef Environmental Changes) conducted by the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD) Science Operator (ESO). We thank the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority for permissions. Funding was provided by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FE 615/4-1), Australian Research Council (Discovery grant DP1094001), Australia and New Zealand IODP Consortium, Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering, Natural Environmental Research Council (NE/H014136/1, NE/H014268/1), the Cooperative Research Program of the Center for Advanced Marine Core Research (10B039, 11A013, 11B041), Ministry of Earth Sciences, Govt. of India (with partial support from DST & ISRO-GBP) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS NEXT-GR031). We thank M. Kölling, S. Pape, M. Segl, C. Vogt, O. Mund, J. Cowley, L. McMorrow, H. Scott-Gagan, J. Abrantes, J. Gaudry, H. Schofield, T. Okai and T. Ishimura for analytical and technical support; A. Timmermann and P.N. DiNezio for discussion; K. Tachikawa for providing data; Expedition 325 project manager C. Cotterill; the crew and drilling team of the Greatship Maya; and the IODP Bremen Core Repository for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.F., H.V.M., B.K.L., A.W.T., A.S., M.I., M.K.G., M.T. and Y.Y. were responsible for coral geochemical analysis; A.L.T., T.M.E. and W.G.T. carried out coral U-Th dating; D.C.P. provided modern corals; M.M. performed statistical analyses; Y.Y. and J.M.W. were Expedition 325 co-chief scientists; T.F., B.K.L., A.W.T., M.K.G., A.S., M.I., A.L.T., T.M.E., W.G.T., M.T. and D.C.P. were Expedition 325 scientists; T.F. was responsible for data compilation and wrote the manuscript together with H.V.M., M.K.G., A.W.T. and B.K.L.; all authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Notes 1-2, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 16974 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Felis, T., McGregor, H., Linsley, B. et al. Intensification of the meridional temperature gradient in the Great Barrier Reef following the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat Commun 5, 4102 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5102

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5102

This article is cited by

-

Mid-Holocene expansion of the Indian Ocean warm pool documented in coral Sr/Ca records from Kenya

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Unbiased Proxy Calibration

Mathematical Geosciences (2023)

-

Response of the Great Barrier Reef to sea-level and environmental changes over the past 30,000 years

Nature Geoscience (2018)

-

Rapid glaciation and a two-step sea level plunge into the Last Glacial Maximum

Nature (2018)

-

Use of skeletal Sr/Ca ratios to determine growth patterns in a branching coral Isopora palifera

Marine Biology (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.