Abstract

Quantum teleportation can transfer information between physical systems, which is essential for engineering quantum networks. Of the many technologies being investigated to host quantum bits, photons have obvious advantages as ‘pure’ quantum information carriers, but their bandwidth and energy is determined by the quantum system that generates them. Here we show that photons from fundamentally different sources can be used in the optical quantum teleportation protocol. The sources we describe have bandwidth differing by a factor over 100, but we still observe teleportation with average fidelity of 0.77, beating the quantum limit by 10 standard deviations. Furthermore, the dissimilar nature of our sources exposes physics hidden in previous experiments, which we also predict numerically. These phenomena include converting qubits from Poissonian to Fock statistics, quantum interference, beats and teleportation for spectrally non-degenerate photons, and acquisition of evolving character following teleportation of a qubit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computer nodes may be based on systems such as linear optics1,2, ions3,4 nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond5,6, semiconductor quantum dots7,8 or spins in silicon9. Interfacing any of these platforms with optical networks will require quantum teleportation protocols10 mediated by light, to transfer the information11,12. However, every demonstration so far of teleportation using linear optics use the same13,14 or identical15,16 sources for the input and entangled photons, often accompanied by a fourth heralding photon15.

Linear optics quantum teleportation requires HOM-type (Hong–Ou–Mandel-type) interference17,18 between the input qubit and one ancilla photon from an entangled photon pair10,13. In a HOM interferometer, two-photon interference on a beam splitter results in bosonic coalescence of pairs of indistinguishable photons in the same output arm. This effect is commonly observed as a reduction of photon pairs in opposite output arms, and requires a balanced beam splitter for maximum visibility. Alternatively, two-photon interference may be observed as an increase of photon pairs in the same output arm, which has maximum visibility for any beam-splitter ratio.

In our experiments, input photons are generated by a laser, and teleported using dissimilar, polarization-entangled photon pairs electrically generated by an entangled-light-emitting diode (ELED)19. This is a significant leap towards practical applications, such as extending the range of existing quantum key distribution systems using quantum relays20 and repeaters21, which usually use weak coherent laser pulses for quantum information transport. Furthermore, though in principle a 50:50 beam splitter may be used to interfere input and entangled photons, we use a 95:5 unbalanced beam splitter, which allows efficient use of the photons produced by the quantum dot emitter.

Results

Quantum interference with an unbalanced beam splitter

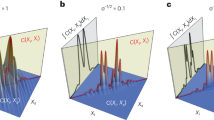

Interactions between dissimilar photons mediated by our unusual beam splitter are probed using the set-up illustrated schematically in Fig. 1a, implemented using single mode fibre components and single-photon counting detectors. Biexciton (XX) photons generated by the quantum dot within the ELED are fed into input port a1 of the unbalanced beam splitter, which couples with 95% efficiency to output mode a3, and the continuous wave laser is fed to input port a2 with coupling 5% to port a3. Using a balanced beam splitter at port a3, we measure second-order correlations for co-polarized (interfering) and cross-polarized (non-interfering) inputs.

(a) Schematic drawing of set-up implemented in fibre optics. Modes a1–a3 couple with 95% efficiency, a2–a3 with 5%. Arrows indicate polarization of sources for interfering measurements. Non-interfering measurements are achieved by rotating the laser polarization by 90°. A spectrometer in mode a4 is used for monitoring purposes and controlling the source detunings. (b) Second-order correlation functions as a function of laser-biexciton photon detuning ΔE, exhibiting interference and quantum beats. Correlations with ΔE>0 have been offset for clarity. For ΔE=0 both interfering (red) and non-interfering (black) correlations are shown. Grey dashed line shows the predicted position of one quantum beat period. (c) Post-selected two-photon interference visibility as a function of detuning. Red dashed curve shows simulated visibility. Error bars indicate 1 s.d.

The measured second-order correlation functions  for interfering photons are shown in Fig. 1b for increasing detuning between laser and biexciton photons ΔE. For zero detuning (bottom correlation), we also show the second-order correlations

for interfering photons are shown in Fig. 1b for increasing detuning between laser and biexciton photons ΔE. For zero detuning (bottom correlation), we also show the second-order correlations  for non-interfering, orthogonally polarized photons, which shows a clear dip originating from the sub-Poissonian photon stream, in contrast to the clear peak in the co-polarized correlation. This peak originates from direct observation of the ‘bunching’ behaviour due to bosonic coalescence in a3, in contrast to previous experiments that usually observe an absence of coincidences in opposite output ports a3 and a4 (refs 17, 18, 22).

for non-interfering, orthogonally polarized photons, which shows a clear dip originating from the sub-Poissonian photon stream, in contrast to the clear peak in the co-polarized correlation. This peak originates from direct observation of the ‘bunching’ behaviour due to bosonic coalescence in a3, in contrast to previous experiments that usually observe an absence of coincidences in opposite output ports a3 and a4 (refs 17, 18, 22).

As we increase the detuning quantum beats with increasing frequency appear in the correlations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first observation of beats of this kind for a quantum dot emitter. In Fig. 1b, one can see that the energy detuning narrows the central peak in  , reducing the magnitude of the observed bunching as the beat period approaches the detector time resolution (∼80 ps). Figure 1c summarizes this effect in terms of observed and simulated peak interference visibility

, reducing the magnitude of the observed bunching as the beat period approaches the detector time resolution (∼80 ps). Figure 1c summarizes this effect in terms of observed and simulated peak interference visibility  . The interference is surprisingly robust, with appreciable visibility after 15 μeV, and beats still visible at 40 μeV, several times larger than the biexciton linewidth of 2ħ/τc∼8 μeV.

. The interference is surprisingly robust, with appreciable visibility after 15 μeV, and beats still visible at 40 μeV, several times larger than the biexciton linewidth of 2ħ/τc∼8 μeV.

The presence of high-visibility interference despite detuning and decoherence of the biexciton photons, can be attributed to the time delay measurement in our experiments, which temporally post-selects photons emitted coincidentally acting as a quantum eraser. Provided the temporal resolution is less than the photon coherence time and quantum beat period, strong interference can be detected, robust against detuning. For the experiments described below, we estimate the efficiency of the temporal post-selection to be ∼6% (see Methods).

Quantum teleportation

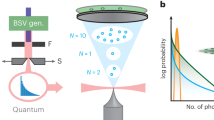

To implement quantum teleportation, we use the set-up shown schematically in Fig. 2a; on the input the ELED is no longer polarized, and the exciton photon (X) originating from the quantum dot within the ELED is now sent to a receiving node (Bob) equipped with a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) and single-photon counting detectors. On the output of the 95:5 splitter, the 50:50 beam splitter is replaced with a PBS, calibrated to measure in the rectilinear basis of the quantum dot exciton (X) eigenstates H–V. The 95:5 splitter, the PBS and the detectors D1 and D2 now constitute a Bell-state measurement apparatus, which we will simply refer to as Alice from now on. A coincident detection by Alice (τ1=0) marks a successful Bell-state measurement which projects the biexciton and laser photons at the input of the 95:5 splitter onto the Bell state  , and signals the successful teleportation of the laser input polarization state onto Bob’s exciton photon (up to a trivial unitary transformation). The time τ2 of Bob’s detection events is measured relative to the triggering of detector D1, and we record third-order correlation functions23.

, and signals the successful teleportation of the laser input polarization state onto Bob’s exciton photon (up to a trivial unitary transformation). The time τ2 of Bob’s detection events is measured relative to the triggering of detector D1, and we record third-order correlation functions23.

(a) Schematic of experimental set-up. Input laser photons interfere with biexciton (XX) photons from an ELED using an unbalanced 95:5 beam splitter. Horizontal (H) and vertical (V) polarized are measured with a PBS and detectors D1 and D2. Teleported exciton (X) photons are measured with another PBS and detectors D3 and D4 (see Methods). (b) Influence of quantum dot to laser intensity ratio η/α2 and detuning ΔE on output fidelity for a superposition input state. (c) Surface plot showing average teleportation fidelity over six input states. Projections on sidewalls show cuts through experimentally measured 2D fidelity map for τ1=0 and τ2=0 (black dots), along with simulated fidelity (red curve). (d) Experimental (red) and simulated (blue) output fidelity for the six input states. (e) Photon statistics of the input (red) and output beams (black) of the teleporter. All error bars indicate 1 s.d.

We simulate teleportation for different laser intensities and detunings (see Methods for details) using a model that takes the finite photon interference, the quantum dot exciton fine-structure and Poissonian statistics of the laser into account. The results, shown in Fig. 2b, suggests that to achieve <1% reduction of teleportation fidelity of a superposition input state such as  , the energy detuning needs to be ≲10 μeV. We select the experimental laser intensity α2 relative to the fixed quantum dot intensity η (measured at D1 and D2) such that η/α2=2, and predicted fidelity is close to maximum.

, the energy detuning needs to be ≲10 μeV. We select the experimental laser intensity α2 relative to the fixed quantum dot intensity η (measured at D1 and D2) such that η/α2=2, and predicted fidelity is close to maximum.

We test the quantum teleportation protocol for six input laser polarization states symmetrically distributed over the Poincaré sphere in three polarization bases; the rectilinear basis H/V coinciding with Alice’s logical measurement basis, the diagonal basis spanned by  and the circular basis

and the circular basis  For each input state, we measure the teleportation fidelity onto the expected output state by aligning Bob to the corresponding basis. For our choice of input states, the highest possible average output fidelity is 2/3 using the best possible classical teleporter23. For coincident detection by Alice and Bob (τ1=τ2=0), we achieve 0.767±0.012 as shown in Fig. 2c, clearly beating the classical limit and proving that quantum teleportation is taking place. Also shown are cuts through the average teleportation fidelity map at τ1=0 and τ2=0, together with a comparison with the model showing good agreement. At τ1=0 along Bob’s time axis τ2, the peak width is limited by the biexciton–exciton polarization correlations, and for τ2=0 along Alice’s time axis τ1 the peak is limited by the biexciton coherence time τc.

For each input state, we measure the teleportation fidelity onto the expected output state by aligning Bob to the corresponding basis. For our choice of input states, the highest possible average output fidelity is 2/3 using the best possible classical teleporter23. For coincident detection by Alice and Bob (τ1=τ2=0), we achieve 0.767±0.012 as shown in Fig. 2c, clearly beating the classical limit and proving that quantum teleportation is taking place. Also shown are cuts through the average teleportation fidelity map at τ1=0 and τ2=0, together with a comparison with the model showing good agreement. At τ1=0 along Bob’s time axis τ2, the peak width is limited by the biexciton–exciton polarization correlations, and for τ2=0 along Alice’s time axis τ1 the peak is limited by the biexciton coherence time τc.

Figure 2d shows the simulated and experimentally measured teleportation fidelities for individual laser polarization settings. The logical states show the highest fidelity as expected (fH→V=0.835±0.026 and fV→H=0.861±0.024), as these do not require two-photon interference, and require only classically correlated photon pairs. The four superposition states, which rely on both successful interference and entanglement, have similar output fidelities (fD→D=0.725±0.032, fA→A=0.698±0.033, fR→L=0.744±0.028 and fL→R=0.741±0.031). The slightly higher fidelity in the circular basis compared with the diagonal is consistent with polarization correlations observed for this type of quantum dot, which can be attributed to nuclear polarization fluctuations in the quantum dot19,24.

During the teleportation experiment, we simultaneously perform a Hanbury Brown Twiss measurement to determine the second-order correlation function of the exciton photons going down the optical fibre to Bob. We find a characteristic dip with minimum  (0)∼0.257±0.001, which confirms that the set-up erases the Poissonian statistical nature of the input laser field, thus eliminating errors if used in a quantum optics circuit.

(0)∼0.257±0.001, which confirms that the set-up erases the Poissonian statistical nature of the input laser field, thus eliminating errors if used in a quantum optics circuit.

To explore the physics of the teleportation process, we perform single-qubit tomography25 of the output photon density matrix corresponding to input state R by measuring the output teleportation fidelity in the three bases H/V, D/A and R/L. For a perfect quantum teleportation, one would expect input R to yield output L with unit fidelity and fidelity 0.5 in the other bases. At τ1=τ2=0, we measure fidelities fR→L=0.713±0.031, fR→D=0.646±0.034 and fR→H=0.550±0.033 from which we construct the real and imaginary parts of the output state density matrix shown in Fig. 3a,b. Of these states, the maximum fidelity is found for the expected output state L, and it is the same as in Fig. 2d within the accuracy of the experiment, but the measurements also reveal a relatively strong D component which results in the non-zero off-diagonal imaginary components in Fig. 3b.

Density matrix of photon received by Bob when teleporting R-polarized laser photons, showing real (a) and imaginary (b) parts, respectively. Experimental data, thick red bars; simulated data, thin blue bars. (c) Maximum eigenvalue of the density matrix as a function of Bob’s detection time. Error bars are 1 s.d. (d) Measured overlap between the optimal output state |ν1〉 with the desired output state L (black squares) and orthogonal state R (red triangles), respectively, showing time evolution with period determined by the exciton FSS∼2 μeV. Black and red curves show corresponding calculated behaviour.

Figure 3c shows the largest eigenvalue λ1 of the density matrix as a function of Bob’s detection time τ2, with a peak value of 0.763±0.030. This exceeds the output fidelity to L, and confirms that Bob’s measurement was not optimally aligned to the output state. As τ2 increases, the exciton photon detected by Bob is no longer from the same radiative cascade as the biexciton photon detected by Alice, and λ1 approaches 1/2 when the output becomes completely mixed. Experimentally, we can follow the evolution of the output state eigenvector |ν1〉 up to τ2∼1 ns after which the uncertainty becomes too large. Figure 3d depicts the overlap of this pure state with the desired state L and the orthogonal counterpart R, showing a clear evolution of the output from L towards R. The numerical model, in contrast to the experiment, is noise-free and a pure fraction (albeit still asymptotically vanishing for large τ2) can always be separated, and as shown in Fig. 3d, the predicted output state evolution is well-described by the fine-structure splitting (FSS) (∼2 μeV) of the exciton state, and agrees qualitatively well with the experimental observations. Note that measurements and calculations for τ2<0 are not well defined due to the suppression of exciton photon emission preceding that of a biexciton photon, and behaviour is heavily influenced by detector jitter and photon pairs emitted with small positive τ2.

Discussion

We have performed quantum teleportation of input states encoded on photons from a coherent light source, to a stream of photons from a sub-Poissonian semiconductor emitter. With further improvements of the device design, such as placing the emitter in an optical nanocavity26,27, the teleportation method presented here could find application in, for example, the realization of quantum relays and repeaters for dissimilar light sources. The protocol used here, with a strongly unbalanced beam splitter, could also provide a useful interface to remotely initialize quantum information processors using abundant laser-generated photons over long distances, and conserving more exotic sub-Poissonian light fields in the local quantum circuit. Other interesting applications could be to secure quantum key distribution networks, usually implemented using weak lasers, from Trojan horse attacks28.

Methods

Entangled-light-emitting diode

The entangled light source incorporates InAs/GaAs quantum dots in a p-i-n diode structure, with a weak optical cavity19. The device is operated at ∼15 K in with d.c. driving current 90 nAμm−2. The dot has small exciton FSS of 2.0±0.2 μeV, and biexciton photon coherence time τc of 161±4 ps, measured with a Michelson interferometer. The exciton and biexciton emission wavelengths were 889.6 and 888.4 nm, respectively. The quantum interference, six-state teleportation and single-qubit teleportation tomography results are from three independent experiments.

Fibre-based optical circuits

The optical circuits schematically described in Figs 1a and 2a were all implemented in single-mode fibre using unbalanced (95:5) and balanced (50:50) beam splitters, PBS and polarization controllers. A tuneable spectral filter picks out the exciton and biexciton photons without narrowing the transition linewidths. Polarizations in the fibre system were aligned to an external calibration laser beam coupled into the fibre system at the same point as the ELED emission.

For two-photon interference (Fig. 1a) and for the Bell measurement apparatus (Fig. 2a) superconducting single-photon counting detectors D1 and D2 were employed. In teleportation experiments, Bob was in possession of avalanche photodiodes D3 and D4. All times were measured in relation to a triggering detection event on D1. The experimentally determined pair-wise detector resolutions were; D1–D2: 80 ps, D1–D3: 340 ps, D1–D4: 360 ps. Port a4 of the 95:5 beam splitter (Figs 1a and 2a) was used to monitor the laser and the biexciton spectral detuning using a grating spectrometer and charge-coupled device camera. Through computer control of the external cavity of the tuneable diode laser, we were able to select a desired detuning and maintain with an estimated accuracy of ∼5 μeV.

PBS and electrical polarization controllers at the sources (not shown) allow us to periodically alternate between measuring co-polarized (interfering) and cross-polarized (non-interfering) photons throughout the two-photon interference experiments. Similarly, in teleportation measurements the polarization state of the input laser photons was periodically switched between orthogonal states (D–A, H–V and R–L).

Temporal post-selection

Temporal selectivity was defined by time bins of 48 ps in τ1 and 240 ps in τ2. Increasing the width of these time bins results in an approximately linear increase in detected and simulated three-photon coincidence intensity, and a reduction in average teleportation fidelity. It is not straight forward to define the efficiency of post-selection, as a reference intensity is not well-defined for continuous wave excitation. We choose a reference intensity defined by the temporal width of the biexciton–exciton correlation of 240 ps in τ2, and the radiative lifetime of the biexciton state of 528 ps in τ1 (rounded up to a time-bin boundary). The resulting efficiency of our detected and calculated coincidence intensity is 6.0% and 7.3%, respectively. We note that experimental quantum teleportation with average fidelity >2/3 is observed for weaker post-selection with up to 44.3% efficiency.

Error analysis

The main source of uncertainty is due to Poissonian counting statistics. Quoted errors on teleportation fidelities also include an uncertainty in time calibration of the photon correlation equipment (<1% on individual fidelities). Errors in Fig. 3 are estimated by propagating the counting statistics from the raw data.

Modelling unbalanced two-photon interference

The simulated two-photon interference visibilities for an unbalanced beam splitter shown in Fig. 1c are based on a well-established wavepacket analysis29,30. By considering different cases that can lead to coincident detections at detectors D1 and D2, we can estimate the second-order correlation function for co-polarized laser and ELED22:

where η is proportional to the biexciton photon intensity and α2 is proportional to the laser intensity measured at detectors D1 and D2, τc is the coherence time of the biexciton photons and ΔE is the biexciton to laser energy detuning.  is the biexciton transition second-order auto-correlation function, separately measured and analytically fitted. By convolving the above expression with the instrument response for detectors D1–D2, we arrive at the simulated interference visibility presented in Fig. 1c.

is the biexciton transition second-order auto-correlation function, separately measured and analytically fitted. By convolving the above expression with the instrument response for detectors D1–D2, we arrive at the simulated interference visibility presented in Fig. 1c.

Modelling heterogeneous quantum teleportation

Detecting two photons on Alice’s detectors D1 and D2, where D1 and D2 resolve orthogonal polarizations H and V in the same arm of the beam splitter, effectively projects the detected photons onto the Bell state  , compared with

, compared with  in most quantum teleportation set-ups. Here 1 and 2 refer to the input ports of the beam splitter, as labelled in Fig. 1a, and

in most quantum teleportation set-ups. Here 1 and 2 refer to the input ports of the beam splitter, as labelled in Fig. 1a, and  and

and  are the Bell states. Ideally, the exciton–biexciton pairs emitted by the quantum dot would be in the Bell state

are the Bell states. Ideally, the exciton–biexciton pairs emitted by the quantum dot would be in the Bell state  . With some algebra, we find that for an arbitrary laser input polarization α|H2〉+β|V2〉, we should find the teleported state received by Bob to be α|VX〉+β|HX〉. This means the following set of transformations imposed by the teleportation operation, which is consistent with the experimental results: H→V, V→H, D→D, A→A, R→L and L→R.

. With some algebra, we find that for an arbitrary laser input polarization α|H2〉+β|V2〉, we should find the teleported state received by Bob to be α|VX〉+β|HX〉. This means the following set of transformations imposed by the teleportation operation, which is consistent with the experimental results: H→V, V→H, D→D, A→A, R→L and L→R.

Using the same wave packet analysis as for two-photon interference as a foundation, we can calculate the probability that Bob detects a certain polarization state given a particular input laser polarization23. As an example, the three-fold coincidence probability (Alice H,V, Bob D) for input state  is

is

for detections by Bob at times later than both of Alice’s detections (τ2>0 and τ2>τ1). Here γx is the lifetime of the exciton photon emitted after the biexciton photon. The effects of exciton FSS (s) and laser-quantum dot detuning ΔE is apparent as oscillations in this expression, as well as the importance of the coherence properties of the biexciton photons (τc).

In principle, the model above could let us calculate the fidelity of the detected photons for an idealized source, but PHVD(τ1,τ2) does not take the actual device driving conditions into account. As a full model of the quantum dot states and all associated transition rates is difficult to realize, we take a semi-empirical approach to predict the performance of our teleporter. Under d.c. excitation all photon pairs detected are not from the same radiative cascade, that is, they are not correlated, and we formulate a probability that Bob detects D (conditional on Alice detecting H–V) taking uncorrelated emission at rate Γ into account:

Similar expressions can be formulated for the degree of polarization correlation of the photon pair XX–X, which allows us to extract the parameters  =0.45 ns−1 and γx=2.5 ns−1 from independently measured polarization correlation measurements.

=0.45 ns−1 and γx=2.5 ns−1 from independently measured polarization correlation measurements.

Experimentally we measure third-order correlation functions  and

and  , with Bob simultaneously recording the orthogonal polarizations D and A on his detectors, and we calculate the teleportation fidelity as

, with Bob simultaneously recording the orthogonal polarizations D and A on his detectors, and we calculate the teleportation fidelity as

To simulate the third-order correlation functions for the experimental set-up at hand, we must take all cases that can lead to triple detections into account (similar to equation 1 above):

where α2 and η are proportional to the laser and quantum dot biexciton intensities, respectively, as measured on detectors D1 and D2. The term with FD(τ1,τ2) corresponds to the wanted case with one photon originating from the laser and one from the quantum dot. The second and third terms correspond to unwanted triples where all photons originate from the ELED or the laser, respectively. Again, full theoretical modelling of the quantum dot to calculate  is beyond the scope of this paper, and as in the case of

is beyond the scope of this paper, and as in the case of  in equation 1, we use empirical fits that agree well with experimentally measured correlations.

in equation 1, we use empirical fits that agree well with experimentally measured correlations.

After convolving with the experimentally determined detector time response functions, we find that the modelled third-order correlations have good qualitative agreement with measurements, and allow us to make the predictions of suitable laser to quantum dot intensity ratios and requirements on source detuning presented in Fig. 2b, as well as the simulations presented in Fig. 3.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Stevenson, R. M. et al. Quantum teleportation of laser-generated photons with an entangled-light-emitting diode. Nat. Commun. 4:2859 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3859 (2013).

References

Kok, P. et al. Linear optical quantum computing. Rev. Modern Phys. 79, 135–179 (2007).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Milburn, G. J. A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature 409, 46–52 (2001).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computations with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091–4094 (1995).

Monroe, C., Meekhof, D. M., King, B. E., Itano, W. M. & Wineland, D. J. Demonstration of a fundamental quantum logic gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4714–4717 (1995).

Neumann, P. et al. Multipartite entanglement among single spins in diamond. Science 320, 1326–1329 (2008).

Weber, J. R. et al. Quantum computing with defects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8513–8518 (2010).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Driven coherent oscillations of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 442, 766–771 (2006).

Shulman, M. D. et al. Demonstration of entanglement of electroscatically coupled singlet-triplet qubits. Science 336, 202–205 (2012).

Kane, B. E. A silicon-based nuclear spin quantum computer. Nature 393, 133–137 (1998).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895–1899 (1993).

Riebe, M. et al. Deterministic quantum teleportation with atoms. Nature 429, 734–737 (2004).

Barrett, M. D. et al. Deterministic quantum teleportation of atomic qubits. Nature 429, 737–739 (2004).

Bouwmeester, D. et al. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 390, 575–579 (1997).

Boschi, D., Branca, S., De Martini, F., Hardy, L. & Popescu, S. Experimental realization of teleporting an unknown pure quantum state via dual classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1121–1125 (1998).

Ma, X.-S. et al. Quantum teleportation over 143 kilometres using active feed-forward. Nature 489, 269–273 (2012).

Halder, M. et al. Entangling independent photons by time measurement. Nat. Phys. 3, 692–695 (2007).

Hong, C. K., Ou, Z. Y. & Mandel, L. Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2044–2046 (1987).

Santori, C., Fattal, D., Vuckovic, J., Solomon, G. S. & Yamamoto, Y. Indistinguishable photons from a single-photon device. Nature 419, 594–597 (2002).

Salter, C. L. et al. An entangled-light-emitting diode. Nature 465, 594–597 (2010).

Jacobs, B. C., Pittman, T. B. & Franson, J. D. Quantum relays and noise suppression using linear optics. Phys. Rev. A 66, 052307 (2002).

Briegel, H.-J., Dür, W., Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum repeaters: the role of imperfect local operations in quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5932–5935 (1998).

Bennett, A. J., Patel, R. B., Nicoll, C. A., Ritchie, D. A. & Shields, A. J. Interference of dissimilar photon sources. Nat. Phys. 5, 715–717 (2009).

Nilsson, J. et al. Quantum teleportation using a light-emitting diode. Nat. Photon. 7, 311–315 (2013).

Stevenson, R. M. et al. Coherent entangled light generated by quantum dots in the presence of nuclear magnetic fields. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.2969 (2011).

Altepeter, J. B., Jeffrey, E. R. & Kwiat, P. G. Photonic state tomography. Adv. Atom. Mol. Opt. Phys. 52, 105–159 (2005).

Dousse, A. et al. Ultrabright source of entangled photon pairs. Nature 466, 217–220 (2010).

Pooley, M. A. et al. Controlled-NOT gate operating with single photons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 211103 (2012).

Lo, H.-K. & Chau, H. F. Unconditional security of quantum key distribution over arbitrarily long distances. Science 283, 2050–2056 (1999).

Legero, T., Wilk, T., Kuhn, A. & Rempe, G. Time-resolved two-photon quantum interference. Appl. Phys. B 77, 797–802 (2003).

Patel, R. B. et al. Quantum interference of electrically generated single photons from a quantum dot. Nanotechnology 21, 274011 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge partial financial support through the European Union Initial Training Network Spin Effects for Quantum Optoelectronics (SPIN-OPTRONICS) and the Seventh Framework Programme Future and Emerging Technologies Collaborative Project Quantum Interfaces, Sensors and Communication Based on Entanglement (Q-ESSENCE), the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the Cambridge Overseas Trust. The authors also thank C. Salter for support in device fabrication, and M. B. Ward for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samples were grown by I.F. and D.A.R. and processed by J.S.-S. and J.N. Optical measurements were made by J.N. and R.M.S and calculations were performed by J.N. A.J.S. guided the work. All authors discussed the experiments, results and their interpretation. R.M.S., J.N. and A.J.B. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stevenson, R., Nilsson, J., Bennett, A. et al. Quantum teleportation of laser-generated photons with an entangled-light-emitting diode. Nat Commun 4, 2859 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3859

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3859

This article is cited by

-

Applications of single photons to quantum communication and computing

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Quantum teleportation with imperfect quantum dots

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Recent advances in nanowire quantum dot (NWQD) single-photon emitters

Quantum Information Processing (2020)

-

An entangled-LED-driven quantum relay over 1 km

npj Quantum Information (2016)

-

Quantum teleportation with independent sources and prior entanglement distribution over a network

Nature Photonics (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.