Abstract

Rising petroleum costs, trade imbalances and environmental concerns have stimulated efforts to advance the microbial production of fuels from lignocellulosic biomass. Here we identify a novel biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel fuel, bisabolane, and engineer microbial platforms for the production of its immediate precursor, bisabolene. First, we identify bisabolane as an alternative to D2 diesel by measuring the fuel properties of chemically hydrogenated commercial bisabolene. Then, via a combination of enzyme screening and metabolic engineering, we obtain a more than tenfold increase in bisabolene titers in Escherichia coli to >900 mg l−1. We produce bisabolene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (>900 mg l−1), a widely used platform for the production of ethanol. Finally, we chemically hydrogenate biosynthetic bisabolene into bisabolane. This work presents a framework for the identification of novel terpene-based advanced biofuels and the rapid engineering of microbial farnesyl diphosphate-overproducing platforms for the production of biofuels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethanol, the most widely used renewable liquid transportation fuel1, has only 70% of the energy content of gasoline and its hygroscopicity makes it incompatible with existing fuel, storage and distribution infrastructure2. Advanced biofuels with high-energy content and physicochemical properties similar to petroleum-based fuels may be better alternatives, as they would allow use of existing engine designs, distribution systems and storage infrastructure3. The challenge lies in identifying and producing a biofuel with fuel and physicochemical properties similar to petroleum-based fuels.

Terpenes, traditionally used as fragrances and flavours4, have the potential to serve as advanced biofuel precursors5,6. For example, the fully reduced form of the linear terpene farnesene is being pursued as an alternative biosynthetic diesel in the market7. Terpenes are biosynthesized from the C5 universal precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). Prenyltransferases assemble IPP and DMAPP into linear prenyl diphosphate precursors, such as farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), which are rearranged by terpene synthases into a variety of different terpenes, such as sesquiterpenes (C15).

Although plants are the natural source of terpenes, engineered microbial platforms may be the most convenient and cost-effective approach for large-scale production of terpene-based advanced biofuels2. Previously, we engineered the mevalonate pathway in both Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for overproduction of FPP8,9. Introduction of a sesquiterpene synthase to these engineered organisms has allowed the production of a variety of sesquiterpenes8,9,10, albeit not in large enough quantities to serve as biosynthetic precursors to advanced biofuels. For example, amorphadiene, a key intermediate in the semi-synthesis of the antimalarial drug artemisinin, can be produced by introduction of amorphadiene synthase that cyclizes FPP. Amorphadiene is currently the most highly produced sesquiterpene at ~750 mg l−1 in S. cerevisiae11 and ~500 mg l−1 in E. coli12 in shake flasks and 27 g l−1 in E. coli, using fermentors13.

We propose that the generality of the microbial FPP overproduction platforms should allow for the biosynthesis of sesquiterpenes to serve as advanced biofuel precursors by introduction of a sesquiterpene synthase producing the desired compound. The viability of this strategy hinges on identifying a sesquiterpene biofuel precursor, and a sesquiterpene synthase able to microbially produce the desired compound in high titers. Adding to the complexity of this proposition is the limited commercial availability of sesquiterpenes to derivatize and test for fuel properties, and the fact that most sesquiterpene synthases are of plant origin and thus potentially difficult to express in microbes.

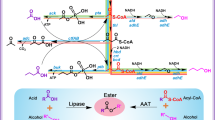

Here we report the identification of a novel biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel fuel, bisabolane, and the engineering of microbial platforms for the overproduction of its immediate precursor, bisabolene (Fig. 1). Hydrogenation of commercially available bisabolene led to the identification of bisabolane as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel. Then, we engineered microbial platforms to produce bisabolene (1), the immediate precursor to bisabolane (2). First, using microbial platforms for the overproduction of FPP, we screened for sesquiterpene synthases able to convert FPP into bisabolene in high titers. Second, we optimized the mevalonate pathway in E. coli for increased bisabolene production by codon-optimization of heterologous pathway genes and introduction of extra promoters to increase expression of key enzymes in the pathway. Third, we produced bisabolene in S. cerevisiae, a widely used platform for the production of ethanol. Finally, we demonstrated the conversion of biosynthetic bisabolene into bisabolane using chemical hydrogenation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a reduced monocyclic sesquiterpene, bisabolane, as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel, and the first microbial overproduction of bisabolene in E. coli and S. cerevisiae at titers over 900 mg l−1 in shake flasks.

The engineered microbe (yellow box) converts simple sugars into acetyl-CoA via primary metabolism. A combination of metabolic engineering of the heterologous mevalonate pathway to convert acetyl-CoA into FPP and enzyme screening to identify a terpene synthase to convert FPP into bisabolene (1) is used to produce bisabolene at high titers. Chemical hydrogenation of biosynthetic bisabolene leads to bisabolane (2), a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel.

Results

Bisabolane as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel fuel

We hypothesized that a fully reduced monocyclic sesquiterpene, bisabolane (2), may serve as a biosynthetic alternative to diesel (Fig. 2). D2 diesel, the fuel for compression ignition engines, is a mixture of linear, branched, and cyclic alkanes with an average carbon length of 16 (3). Among other properties, biosynthetic alternatives to D2 diesel should have a similar cetane number and comparable cold properties14. Bisabolane has a carbon length (C15), close to the average carbon length of diesel (C16). Further, the branching found in the linear portion of bisabolane may result in beneficial fuel cold properties. Finally, the ring portion of bisabolane increases the density of the fuel, which will increase the energy density per volume of fuel. To our knowledge, there are no reports of bisabolane as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel.

To determine whether bisabolane could serve as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel, we chemically hydrogenated commercially available bisabolene and measured its fuel properties. Bisabolene was the major component of commercial bisabolene, which also contained impurities such as farnesene (Fig. 3a). Bisabolane was the major component of the hydrogenated commercial bisabolene representing ~50% of the product profile, followed by farnesane (4) (~20%), partially hydrogenated bisabolene (~20%), and aromatized bisabolene (~7%) (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S1). Table 1 shows the physicochemical and fuel properties of D2 diesel15, biodiesel (5)15, and the hydrogenated commercial bisabolene. The hydrogenated commercial bisabolene has a cetane number of 41.9, which lies within the range of D2 diesel (40–55). Further, hydrogenated commercial bisabolene has better cold properties than those of D2 diesel, with a cloud point of −78 °C as compared with −35 °C, and than those of biodiesel, which has a cloud point of −3 °C. Commercial bisabolene has a cetane number of 30 and is not a D2 diesel alternative. The fuel properties of hydrogenated commercial bisabolene may be impacted by the presence of compounds other than bisabolane in the final product. For example, although farnesane may improve some of the biofuel characteristics such as cetane number, partially hydrogenated and aromatized bisabolenes would deteriorate these same fuel properties. Further, the linear structure of farnesane results in a lower density (0.77 g ml−1) than cyclic bisabolane (0.88 g ml−1). Given the similar ratios of potentially beneficial and detrimental byproducts, we estimate that their effect on the fuel properties will cancel each other out. Therefore, the measured cetane number, which is within the range of D2 diesel, can be primarily attributed to the major product, bisabolane. Taken together, these data demonstrate that bisabolane is a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel fuel.

(a) GC trace of commercial bisabolene. Commercial bisabolene (TCI America: bisabolene B1413) has four major peaks (RT: 8.12, 8.22, 8.59 and 8.92). Peak at RT: 8.92 has the same retention time as biosynthetic bisabolene (α-bisabolene). Peak at RT: 8.12 has the same retention time as a commercial sample of farnesene (Fluka: β-farnesene 73492). Peaks at RT: 8.22 and 8.59 are sesquiterpenes based on the m/z=204. The ratio of bisabolene to farnesene is ~2:1. (b) GC trace of hydrogenated commercial bisabolene. Hydrogenated commercial bisabolene has four main peaks (RT: 7.35, 7.70, 7.98, and 8.08). Peaks at RT: 7.99 and 8.08 have the same retention time as the hydrogenated biosynthetic bisabolene (bisabolane geometric isomers). Peak at RT: 7.35 has the same retention time as hydrogenated commercial farnesene (farnesane). Peak at RT: 7.70 is partially hydrogenated bisabolene based on MS analysis of partial hydrogenation of biosynthetic bisabolene (Supplementary Fig. S1). The ratio of bisabolane to farnesane is ~2.5:1.

Screening enzymes for high bisabolene titers in E. coli

Knowing that bisabolane is a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel, we used a previously engineered E. coli platform for the overproduction of FPP to screen for terpene synthases to convert FPP into a monocyclic sesquiterpene in high titers. The monocyclic sesquiterpene could then be chemically hydrogenated to bisabolane. Briefly, wild-type E. coli uses the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate pathway to convert pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to IPP and DMAPP, the precursors to all terpenes. Previously, we showed that the native deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate pathway in E. coli produces negligible amounts of sesquiterpenes when overexpressing a sesquiterpene synthase8. To increase the production of terpenes, we engineered E. coli to heterologously express the mevalonate pathway from S. cerevisiae to overproduce FPP from acetyl-CoA8. Recently, the eight genes of the heterologous mevalonate pathway were assembled in a single plasmid (pJBEI-2704) to reduce metabolic burden and the number of antibiotic markers12. To screen for terpene synthases that produce monocyclic sesquiterpenes, we transformed E. coli with pJBEI-2704 and a plasmid expressing the terpene synthase gene. Terpene synthase screening was necessary, as these enzymes have been previously identified as bottlenecks in microbial sesquiterpene production16. In nature, plants produce three monocyclic sesquiterpenes that could be chemically hydrogenated to bisabolane: curcumene, zingiberene and bisabolene. For biofuel purposes, we needed to identify a terpene synthase that produces a monocyclic sesquiterpene as its major product. The two known zingiberene synthases in the literature17 produce zingiberene as ≤40% of their product profile and were not included in the screen. The only known curcumene synthase in the literature17, that from patchouli (Pogostemon cablin), produced curcumene in ~90% of its product profile. Therefore, we synthesized the E. coli codon-optimized P. cablin curcumene synthase gene and tested it for curcumene production. However, curcumene was produced at only 130 μg l−1 in our E. coli FPP-overproducing platform.

Five of the six bisabolene synthases known in the literature at the beginning of the project produced bisabolene in >90% of their product profile17. Sequence alignment of the five bisabolene synthases revealed two gene structures depending on their plant origin18 (Fig. 4a). Angiosperm bisabolene synthases, Arabidopsis thaliana (Z)-γ-bisabolene synthases TPS12 and TPS13 (ref. 19), have two domains, making them similar to previously characterized plant sesquiterpene synthases, such as amorphadiene synthase. Gymnosperm bisabolene synthases, Pseudotsuga menziesii (E)-γ-bisabolene synthase TPS3 (ref. 20), and Abies grandis (E)-α-bisabolene synthase Ag1 (ref. 21), and Picea abies (E)-α-bisabolene synthase TPS-BIS22, have three domains, making them structurally closer to diterpene synthases, such as abietadiene synthase, than to sesquiterpene synthases. Not knowing whether gene structure would influence the microbial production of bisabolene, we screened both two- and three-domain bisabolene synthases. We synthesized the E. coli codon-optimized version of the two-domain bisabolene synthases, A. thaliana TPS12 and TPS13. From other laboratories, we obtained the plant genes for two three-domain bisabolane synthases P. menziesii TPS3 and A. grandis Ag1. To test all five bisabolene synthases that produce bisabolene in >90% of their product profile, we synthesized the E. coli codon-optimized version of the last three-domain bisabolene synthase, P. abies TPS-BIS. Figure 4b shows the bisabolene production from each of the five bisabolene synthases. Among the two-domain bisabolene synthases, A. thaliana TPS13 showed the highest bisabolene production at 35±13 mg l−1, whereas A. thaliana TPS12 did not produce detectable levels of bisabolene. Among the three-domain bisabolene synthases, P. abies TPS-BIS did not produce detectable levels of bisabolene, P. meziessi TPS3 produced bisabolene at 4±2 mg l−1 and A. grandis Ag1 produced 78±14 mg l−1 of bisabolene. To further increase bisabolene production, we synthesized the E. coli codon-optimized version of the highest bisabolene-producing gene, A. grandis Ag1, to generate AgBIS. As shown in Figure 4b, AgBIS increased bisabolene production fivefold to 389±49 mg l−1. AgBIS produced α-bisabolene as a single product (Supplementary Fig. S2). The increase in microbial bisabolene production seen with AgBIS when compared with that of Ag1 can be attributed to an increase in soluble expression of the bisabolene synthase enzyme in E. coli (Supplementary Fig. S3).

(a) Gene structure of bisabolene synthases screened. (b) E. coli bisabolene production as a function of bisabolene synthase using pJBEI-2704 as the heterologous mevalonate pathway. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Shown is the mean bisabolene production after 73 h of growth in EZ-rich defined medium with 1% glucose. The error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. CO, gene synthesized using E. coli codon usage. Plant, original plant gene.

Metabolic engineering doubles bisabolene titers in E. coli

With the highest bisabolene-producing gene in hand (AgBIS), we set out to improve the E. coli production of FPP via metabolic engineering of the mevalonate pathway (Fig. 5). For optimization, we conceptually divided the mevalonate pathway into a top portion that converts acetyl-CoA into mevalonate and a bottom portion that converts mevalonate into FPP. The mevalonate pathway is heterologous to E. coli, and the genes encoding truncated HMG-CoA reductase (tHMGR), HMG-CoA synthase (HMGS), mevalonate kinase (MK), phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK), and mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (PMD) are derived from S. cerevisiae8. The E. coli strain harbouring AgBIS with our original heterologous mevalonate pathway (pJBEI-2704) produced 388±49 mg l−1 bisabolene. In the first optimization attempt, we codon-optimized four of the five S. cerevisiae genes present in the mevalonate pathway (tHMGR, HMGS, MK, and PMK) to match the E. coli codon usage to generate pJBEI-2997. We did not codon-optimize PMD, as previous proteomic studies showed high protein levels of PMD12. This platform produced 586±65 mg l−1 bisabolene. To improve expression of the enzymes in the bottom portion of the pathway, we placed these genes under control of a second promoter (Ptrc) (pJBEI-2999). This platform produced 912±43 mg l−1 of bisabolene, which is a twofold improvement in bisabolene production over our original platform. On the basis of the mevalonate pathway-dependent theoretical yield of 0.25 g sesquiterpene per g of glucose5, and assuming that only glucose is being converted to bisabolene, we have reached 36% of apparent theoretical yield using defined rich media with 1% glucose. To determine the actual yield and the percentage of theoretical yield for bisabolene production in E. coli, we used the highest E. coli bisabolene production strain, that is, E. coli harbouring JBEI-2999 and AgBIS, and repeated the shake flask production in minimal medium. The actual yield of bisabolene production is 0.01 g g−1 of glucose (~208 mg l−1 after 72 h with 2% glucose). Therefore, our E. coli platform is at 4% of theoretical yield. The lower yield in minimal medium suggests that more optimization is needed for the use of these strains in minimal medium.

(a) The mevalonate pathway converts acetyl-CoA into FPP in eight enzymatic steps: acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (atoB), truncated HMG-CoA reductase (tHMGR), HMG-CoA synthase (HMGS), mevalonate kinase (MK), phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK), mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (PMD), isoprenyl diphosphate isomerase (idi) and farnesyl diphosphate synthase (ispA). Gene names in uppercase are original genes from S. cerevisiae, and gene names in lowercase are endogenous E. coli genes. Gene names in red have been synthesized to match E. coli codon usage. (b) E. coli bisabolene production as a function of the mevalonate pathway using AgBIS as the bisabolene synthase. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Shown is the mean bisabolene production after 73 h of growth in EZ-rich defined media with 1% glucose. The error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

Engineering bisabolene production in S. cerevisiae

In addition to production in E. coli, we also engineered bisabolene production in S. cerevisiae, a host widely used for production of ethanol (Fig. 6). Specifically, we adapted a previously engineered S. cerevisiae FPP overproduction platform for the production of bisabolene. Briefly, in the S. cerevisiae FPP overproduction platform, the truncated HMG-CoA reductase (tHMGR), the FPP synthase (Erg20), and the global transcription regulator of the sterol pathway upc2-1 were overexpressed and the squalene synthase (Erg9) was downregulated from the chromosome9. We adapted this yeast platform for the production of bisabolene by placing the bisabolene synthases under control of the galactose promoter on a high-copy plasmid (2 μ) containing the auxotrophic Leu2d marker previously used to achieve the highest production of amorphadiene11. Given that in vivo enzymatic activity is sometimes context (organism) dependent9,23, we screened the same bisabolene synthases previously screened in E. coli in S. cerevisiae. Figure 6b shows the bisabolene production from each of the five bisabolene synthases in S. cerevisiae. Neither of the two-domain bisabolene synthases, A. thaliana TPS12 or TPS13, showed detectable levels of bisabolene. Unlike in E. coli, all three-domain sesquiterpene synthases produced bisabolene in S. cerevisiae. P. abies TPS-BIS produced 23±7 mg l−1 bisabolene, P. meziessi TPS3 produced 69±7 mg l−1 bisabolene, and A. grandis Ag1 produced 66±11 mg l−1. Interestingly, the bisabolene productions of P. meziessi TPS3 and A. grandis Ag1 are much closer together in S. cerevisiae than in E. coli. The highest production was achieved using AgBIS at 994±241 mg l−1.

(a) S. cerevisiae strain previously engineered for the production of amorphadiene9 (EPY300) was re-engineered to produce bisabolene by overexpressing bisabolene synthase. In S. cerevisiae, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase is Erg10, isoprenyl diphosphate isomerase is IDI1, and farnesyl disphosphate synthase is Erg20. Gene names in blue (upc2-1, tHMGR, ERG20 and BIS) are overexpressed. (b) S. cerevisiae (EPY300) bisabolene production as a function of bisabolene synthase. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Shown is the mean bisabolene production after 96 h of growth in rich medium (YEP) with 1.8% galactose/0.2% glucose. The error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. CO, gene synthesized using E. coli codon usage. Plant, original plant gene.

Bisabolene shows low toxicity to E. coli and S. cerevisiae

In addition to high microbial titers, the feasibility of bisabolene as a biofuel precursor will depend on the toxicity it imparts to the overproducing organism. Figure 7 shows that commercial bisabolene imparts low to no toxicity to E. coli and S. cerevisiae when added exogenously to the medium. The E. coli and S. cerevisiae cell growth are comparable at 0% (v/v) bisabolene and up to 20% (v/v) of exogenously added bisabolene. Above 20% (v/v) of exogenously added bisabolene, bisabolene phase-separated from the culture medium. The lack of toxicity to the tested microbial platforms should enable the production of bisabolene in high titers.

(a) E. coli growth after 24 h in the presence of 0–20% (v/v) of commercial bisabolene. (b) S. cerevisiae growth after 16 h in the presence of 0–20% v/v of commercial bisabolene. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Shown is the mean growth after overnight growth and the error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

Chemical hydrogenation of biosynthetic bisabolene

To demonstrate that microbially produced bisabolene can be converted to the biosynthetic D2 diesel alternative, bisabolane, we used a palladium on carbon catalyst to chemically reduce biosynthetic bisabolene into fully hydrogenated bisabolanes (Fig. 8). First, we isolated biosynthetic bisabolene from E. coli cell cultures and we assigned its NMR spectra (Supplementary Figs S4–6). Then, we fully reduced the biosynthetic bisabolene into a 3:1 mixture of bisabolanes. Bisabolene was fully hydrogenated to bisabolane as demonstrated by the lack of vinylic protons in the 1 H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S7) and the lack of alkenes and 13C NMR (Supplementary Fig. S8) spectrum. On the basis of the chemical structure of α-bisabolene and the reaction mechanism of Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation, we infer that the bisabolanes are geometric isomers (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Discussion

Here we present a framework for the rapid identification and development of a terpene-based advanced biofuels that sets precedent for the discovery of other advanced biofuels. In the absence of a commercial source of bisabolane, chemical hydrogenation of commercial bisabolene led to the identification of bisabolane as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel. The flexibility of the E. coli and S. cerevisiae FPP-overproducing platforms allowed us to rapidly switch from the overproduction of amorphadiene to that of bisabolene, the immediate precursor to bisabolane. In E. coli, bisabolene synthase screening and codon-optimization followed by metabolic engineering of the heterologous mevalonate pathway led to a tenfold increase in bisabolene titers. In S. cerevisiae, screening of the bisabolene synthases led to bisabolene titers >900 mg l−1, the highest sesquiterpene titer in this organism to date. Further, we showed that bisabolene toxicity is not a limit in the microbial production of bisabolene in either S. cerevisiae or E. coli. Finally, we demonstrated chemical conversion of biosynthetic bisabolene into bisabolane using chemical hydrogenation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a reduced monocyclic sesquiterpene, bisabolane, as a biosynthetic alternative to D2 diesel, and the first microbial overproduction of bisabolene at >900 mg l−1.

It is currently difficult to obtain large quantities of biosynthetic bisabolene to hydrogenate and test its fuel properties. The shake flask production experiments reported in this manuscript have been performed with an organic overlay for analysis purposes. Although both the E. coli and S. cerevisiae strains produce high levels of the sesquiterpene, purification of bisabolene is currently challenging due to co-evaporation of the product and the organic overlay. Further improvements in bisabolene production or an alternative separation technology will be required to obtain the quantities of highly pure bisabolene needed for fuel properties testing. Through multiple rounds of large-scale preparation in shake flasks, we have prepared ~20 ml of biosynthetic bisabolene, hydrogenated it, and performed preliminary fuel properties testing. Though the results are preliminary due to an insufficient sample amount for complete testing, the preliminary cetane number of the hydrogenated biosynthetic bisabolene is 52.6. Once the complete fuel properties of hydrogenated biosynthetic bisabolene can be obtained, we will be able to estimate the impact of byproducts present in the hydrogenated commercial bisabolene, such as farnesane and aromatized bisabolene (Fig. 3b). Given the similar ratios of potentially beneficial (farnesane) and detrimental (aromatized and partially reduced bisabolenes) byproducts in the hydrogenated commercial bisabolene, we estimate that the measured physicochemical properties reported in this work can be largely attributed to the major product, bisabolane.

While bisabolane has physicochemical properties similar to D2 diesel, it must be produced at high yields from the sugar source using a relatively simple process to be economically viable. Here we produced bisabolene in E. coli at ~36% of apparent pathway-dependent theoretical yield, and at 4% of pathway-dependent theoretical yield in minimal medium. We are currently optimizing the fermentation conditions, pathway genes and the organism to improve the productivity in minimal medium and also to produce larger quantities of biosynthetic bisabolene for complete fuel property analysis. Further, the low toxicity of bisabolene to E. coli and S. cerevisiae should allow production of bisabolene at very high titers.

An economic analysis on the production of bisabolene takes into consideration many variables including the cost and type of feedstock, biomass depolymerization method, and the microbial yield of biofuel. Assuming a break-even price of sugar at the mill to be close to US $0.10/lb, which is lower than the current volatile spot price but closer to the long-term nominal price of the commodity, we can perform a rough calculation of the theoretical cost of bisabolene. On the basis of that number, the raw material cost of bisabolene production would be, ignoring non-sugar costs, approximately $0.88 per kg of bisabolene. Assuming raw material costs to be only ~50% of the final cost, this would imply a final cost of $1.76 per kg, or $5.73 per gal of bisabolene on the basis of data for ethanol production24. (We assumed the raw material cost for bisabolene as 50% of total cost which is lower than that of ethanol (66%) on the assumption that the bisabolene production process will be more involved and, thus, more costly than the production of ethanol). At an estimated ~$6 per gal, bisabolene is currently more expensive than current D2 diesel. However, it is still promising to investigate this emerging alternative biofuel when considering its superior properties and renewable nature.

Finally, in this work we have resorted to chemical hydrogenation of bisabolene into the final product bisabolane. While industrially feasible, the ultimate goal is the complete microbial production of bisabolane. This will require the reduction of terpenes in vivo using designer reductases and, potentially, balancing cellular reducing equivalents.

Methods

Hydrogenation of commercial bisabolene

Bisabolene (mixture of isomers) was purchased from TCI America (catalogue No. B1413). 10% Pd/C was purchased from Aldrich (catalogue No. 205699). 25 ml of bisabolene was added in Parr high-pressure reaction vessel with 125 ml glass insert. 250 mg of 10% Pd/C (10 wt % of substrate) was added and the reaction vessel was flushed with hydrogen several times at 500 psi. The reaction mixture was pressurized with hydrogen to 1,200 psi and stirred at 25 °C. The reaction vessel was repressurized to 1,200 psi when the pressure dropped below 100 psi and stirred until no further decrease of hydrogen pressure was observed. The excess hydrogen was removed and the mixture was filtered over celite. The filtrate was dried under high vacuum overnight, and the product was directly used for fuel property test without any further purification.

Cetane number of hydrogenated commercial bisabolene

The cetane number measurements were executed by Dr. Matthew Ratcliff at NREL. The ignition delay of the bisabolene sample or the hydrogenated bisabolene sample (~60 ml) was measured with the Ignition quality tester (IQT), using ASTM D6890-08 and converted to derived cetane number. Further ignition delay measurements were made to determine the sensitivity of hydrogenated bisabolene to combustion temperature, pressure and oxygen concentration. The data were regressed on a modified Arrhenius plot to determine the apparent activation energy (Ea) and the oxygen mole fraction dependency (b).

Properties of hydrogenated commercial bisabolene

The properties were measured at the Southwest Research Institute (San Antonio, Texas). The following ASTM methods were used for each property measurement: cloud point measurement (ASTM D5773), specific gravity or density measurement (ASTM D4052), flash point measurement (ASTM D93), kinetic viscosity measurement (ASTM D445), and boiling point (ASTM D2887).

Bisabolene synthase vectors

For bisabolene production in E. coli, the five bisabolene synthase genes were cloned into vector pTrc99 between NcoI and XmaI sites. The genes were amplified from their respective templates using their respective primers, digested with NcoI and XmaI and cloned into pTrc99. For bisabolene production in S. cerevisiae, the five bisabolene synthase genes were cloned into the vector pRSLeu2d11 between NheI and XhoI sites. The genes were amplified from their respective templates using their respective primers, digested with NheI and XhoI, and cloned into pRSLeu2d.

Mevalonate pathway vectors

pBb plasmids were prepared as the BglBrick standard expression vectors25. The top portion of the mevalonate pathway contains genes for the conversion of acetyl CoA to mevalonate: acetoacetyl-CoA synthase from E. coli (atoB), HMG-CoA synthase from S. cerevisiae (HMGS), and an amino-terminal truncated version of HMG-CoA reductase from S. cerevisiae (HMGR). The bottom portion of the mevalonate pathway contains genes for the conversion of mevalonate toFPP: mevalonate kinase from S. cerevisiae (MK), phosphomevalonate kinase from S. cerevisiae (PMK), phosphomevalonate decarboxylase from S. cerevisiae (PMD), IPP isomerase from E. coli (idi), and farnesyl diphosphate synthase from E. coli (ispA). pJBEI-2704 (pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS): The construction of this plasmids has been previously reported12. pJBEI-2997 (pBbA5c-MevT(CO)-MBIS(CO)): pBbA5c-MevT(CO) was constructed by ligating pBbA5c vector (BamHI/XhoI) and BglBrick compatible codon optimized HMGS and HMGR inserts (BglII/XhoI), using BglBrick cloning strategy with compatible BglII and BamHI restriction. Individual genes were PCR-amplified from pAM45 (ref. 16) with primers contain EcoRI and BglII sites at 5′-end and BamHI and XhoI sites at 3′-end of each gene. The BglBrick restriction sites found in each gene were removed by site-specific mutagenesis. pBbA5c-MevT(CO)-MBIS(CO) was prepared by the ligation of pBbA5c-MevT(CO) vector (BamHI/XhoI) and MBIS with E. coli codon optimized MK and PMK insert (BglII/XhoI). pJBEI-2999 (pBbA5c-MevT(CO)-Ptrc-MBIS(CO)): The plasmid was prepared by two-step ligation of pBbA5c-MevT(CO) vector (BamHI/XhoI) and a double terminator-Ptrc gene part (BglII/XhoI) and MBIS(CO) insert (BglII/XhoI) by standard BglBrick cloning strategy.

Bisabolene production in E. coli

For the bisabolene synthase screen, E. coli DH1 was co-transformed with pJBEI-2704 and either pJBEI-3175 (TPS12), pJBEI-3167 (TPS13), pJBEI-3177 (TPS-BIS), pJBEI-3604 (TPS3), pJBEI-3360 (Ag1), or pJBEI-3361 (AgBIS). For the optimization of the mevalonate pathway, E. coli DH1 was co-transformed with AgBIS and any one of pJBEI-2704, pJBEI-2997, and pJBEI-2999. Pre-cultures of E. coli DH1 harbouring the appropriate plasmids were used to inoculate at a 1:100 dilution bisabolene production media (Teknova, EZ-Rich, 1% (v/v) glucose, amp100, cm30, 50 ml). The cultures were grown at 37 °C for 5.5 h (180 r.p.m., OD600=0.6–0.8) before induction with 500 μM IPTG and overlayed with 20% dodecane. After growth for 73 h at 30 °C (180 r.p.m.), 10 μL of the dodecane overlay were sampled and diluted into 990 μl of ethyl acetate spiked with caryophyllene as an internal standard. The samples were analysed by GC/MS (Thermo Trace Ultra with PolarisQ MS) with a TR-5MS column (30 m×0.25 mm ID ×0.25 μm film) using a cadinene standard curve using the following conditions: inlet at 225 °C, 1.2 ml min−1 constant flow, transfer line at 300 °C, ion source at 200 °C, scan m/z 50–300. Oven: 60 °C for 1 min, ramp at 25 °C min−1 to 220 °C, hold 2 min. For actual yield calculations, we used minimal medium with glucose as the only carbon source. Bisabolene production was executed as described above with E. coli DH1 harbouring JBEI-2999 and pJBEI-3361 in minimal medium (M9 medium supplemented with trace elements, 2% (v/v) glucose, amp100, cm30, 50 ml). After 72 h of growth the dodecane layer was sampled and analysed by GC/FID (Thermo Focus with FID) equipped with a DB-5HT column (10 m×0.32 mm ID ×0.1 μm film), using a caryophyllene standard curve using the following conditions: inlet at 250 °C, FID at 320 °C, 100 kPa constant pressure; oven: 60 °C for 0.75 min, 40 °C min−1 to 200 °C. Glucose was measured via high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) before and during bisabolene production. Glucose was completely consumed after 24 h.

Bisabolene production in S. cerevisiae

Pre-cultures of S. cerevisiae strain EPY300 (ref. 9) transformed with the appropriate plasmid for bisabolene synthase expression was used to inoculate at an OD600 of 0.05 into 5 ml of YEP supplemented with 1.8% galactose/0.2% glucose and overlayed with 10% dodecane. After 96 h of growth at 30 °C, 10 μL of the dodecane layer were sampled and diluted into 990 μl of ethyl acetate spiked with caryophyllene as an internal standard. The samples were analysed by GC/FID (Thermo Focus with FID) equipped with a DB-5HT column (10 m×0.32 mm ID ×0.1 μm film) using a caryophyllene standard curve using the following conditions: inlet at 250 °C, FID at 320 °C, 100 kPa constant pressure; oven: 60 °C for 0.75 min, ramp 40 °C min−1 to 200 °C.

Bisabolene microbial toxicity

To E. coli: an overnight culture of E. coli DH1 harbouring AgBIS and JBEI-2999 was used to inoculate 1 ml cultures containing 0–20% (v/v) of commercial bisabolene (TCI America B1413) at an OD600=0.05 in triplicate. The cultures were grown for at 37 °C for 24 h before the OD600 was measured. To S. cerevisiae: an overnight culture of EPY300 (SD-HIS-MET, 2% glucose) was used to inoculate 1 ml cultures containing 0–20% (v/v) of commercial bisabolene at an OD600=0.05 in triplicate. The cultures were grown for at 30 °C for 16 h before the OD600 was measured.

Purification of biosynthetic bisabolene

The E. coli or S. cerevisiae bisabolene production strains were grown as previously described but overlayed with decane, instead of dodecane, to facilitate bisabolene extraction. The decane overlay was separated from the culture medium using a separatory funnel and dried over sodium sulfate. The decane was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the leftover oil was loaded onto a silica gel column for column chromatography using hexanes as the solvent. The product containing fractions were pooled and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The product was obtained as colourless oil.

Chemical hydrogenation of biosynthetic bisabolene

The biosynthesized bisabolene in dodecane overlay or in hexane for purified bisabolene (60 ml, 1.52 mmol. of bisabolene) was dried under high vacuum overnight and was added into Parr high-pressure reaction vessel with 125-ml glass insert. 100 mg of 10% Pd/C was added and the reaction vessel was flushed with hydrogen several times at 500 psi. The reaction mixture was pressurized with hydrogen to 1,200 psi and stirred at 25 °C overnight. The excess hydrogen was removed and the mixture was filtered over celite. The filtrate was dried under high vacuum, and the product was analysed by GC/MS without any further purification. The reaction mixture in hexane was also filtered over celite, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Peralta-Yahya, P. P. et al. Identification and microbial production of a terpene-based advanced biofuel. Nat. Commun. 2:483 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1494 (2011).

References

United Nations Environment Programme, . Towards sustainable production and use of resources - assessing biofuels (www.unep.fr; http://www.uneptie.org/energy/bioenergy/documents/pdf/Assessing%20Biofuels-Summary-Web-.pdf) (2009).

Peralta-Yahya, P. P. & Keasling, J. D. Advanced biofuel production in microbes. Biotechnol. J. 5 147–162 (2010).

Fortman, J. L. et al. Biofuel alternatives to ethanol: pumping the microbial well. Trends Biotechnol. 26 375–381 (2008).

Kirby, J. & Keasling, J. D. Biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids: perspectives for microbial engineering. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60 335–355 (2009).

Rude, M. & Schirmer, A. New microbial fuels: a biotech perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12 274–281 (2009).

Harvey, B. G., Wright, M. E. & Quintana, R. L. High-density renewable fuels based on the selective dimerization of pinenes. Energ. Fuel. 24 267–273 (2010).

Renniger, N. & McPhee, D. Fuel compositions comprising farnesane and farnesane derivatives and method of making and using same. U.S. Patent No. 7399323 (2008).

Martin, V. J., Pitera, D. J., Withers, S. T., Newman, J. D. & Keasling, J. D. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat. Biotechnol. 21 796–802 (2003).

Ro, D. K. et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature 440 940–943 (2006).

Yoshikuni, Y., Ferrin, T. E. & Keasling, J. D. Designed divergent evolution of enzyme function. Nature 440 1078–1082 (2006).

Ro, D. K. et al. Induction of multiple pleiotropic drug resistance genes in yeast engineered to produce an increased level of anti-malarial drug precursor, artemisinic acid. BMC Biotechnol. 8 83 (2008).

Redding-Johanson, A. M. et al. Targeted proteomics for metabolic pathway optimization: Application to terpene production. Metab. Eng. 13 194–203 (2011).

Tsuruta, H. et al. High-level production of amorpha-4,11-diene, a precursor of the antimalarial agent artemisinin, in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4 e4489 (2009).

Lee, S. K., Chou, H., Ham, T. S., Lee, T. S. & Keasling, J. D. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for biofuels production: from bugs to synthetic biology to fuels. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19 556–563 (2008).

National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Biodiesel handling and use guide (Fourth Edition) (www.nrel.gov; http://www.nrel.gov/vehiclesandfuels/pdfs/43672.pdf) (2009).

Anthony, J. R., Anthony, L. C., Nowroozi, F., Kwon, G., Newman, J. D. & Keasling, J. D. Optimization of the mevalonate-based isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli for production of the anti-malarial drug precursor amorpha-4,11-diene. Metab. Eng. 11 13–19 (2009).

Degenhardt, J., Kollner, T. G. & Gershenzon, J. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants. Phytochemistry 70 1621–1637 (2009).

Trapp, S. C. & Croteau, R. B. Genomic organization of plant terpene synthases and molecular evolutionary implications. Genetics 158 811–832 (2001).

Ro, D. K., Ehlting, J., Keeling, C. I., Lin, R., Mattheus, N. & Bohlmann, J. Microarray expression profiling and functional characterization of AtTPS genes: Duplicated Arabidopsis thaliana sesquiterpene synthase genes At4g13280 and At4g13300 encode root-specific and wound-inducible (Z)-gamma-bisabolene synthases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 448 104–116 (2006).

Huber, D. P., Philippe, R. N., Godard, K. A., Sturrock, R. N. & Bohlmann, J. Characterization of four terpene synthase cDNAs from methyl jasmonate-induced Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii. Phytochemistry 66 1427–1439 (2005).

Bohlmann, J., Crock, J., Jetter, R. & Croteau, R. Terpenoid-based defenses in conifers: cDNA cloning, characterization, and functional expression of wound-inducible (E)-alpha-bisabolene synthase from grand fir (Abies grandis). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95 6756–6761 (1998).

Martin, D. M., Fäldt, J. & Bohlmann, J. Functional characterization of nine Norway spruce TPS genes and evolution of gymnosperm terpene synthases of the TPS-d subfamily. Plant Physiol. 135 1908–1927 (2004).

Chang, M. C., Eachus, R. A., Trieu, W., Ro, D.- K. & Keasling, J. D. Engineering Escherichia coli for production of functionalized terpenoids using plant P450s. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 274–277 (2007).

Von Lampe, P. Agricultural market impacts of future growth in the production of biofuels. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (www.oecd.org; www.oecd.org/dataoecd/58/62/36074135.pdf) (2006).

Anderson, J. C. et al. BglBricks: A flexible standard for biological part assembly. J. Biol. Eng. 4 1 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (http://www.jbei.org) supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the US Department of Energy. We thank Prof. Rodney Croteau at Washington State University for the Abies grandis bisabolene synthase gene (pSBAg1), Prof. Jörg Bohlmann at The University of British Columbia for the Pseudotsuga menziesii bisabolene synthase gene (pPmeTPS3), Dr Matthew Ratcliff at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) for the cetane number measurement, and Dr Daniel Klein-Marcuschamer at JBEI for economic analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.P.-Y., M.O., A.M., J.D.K. and T.S.L. designed the experiments. P.P.-Y., T.S.L., M.O. and R.C. performed the experiments. P.P.-Y., T.S.L. and J.D.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JDK has financial interest in Amyris Biotechnologies and LS9 Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S17, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Methods. (PDF 1281 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Peralta-Yahya, P., Ouellet, M., Chan, R. et al. Identification and microbial production of a terpene-based advanced biofuel. Nat Commun 2, 483 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1494

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1494

This article is cited by

-

A flavin-monooxygenase catalyzing oxepinone formation and the complete biosynthesis of vibralactone

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Highly efficient biosynthesis of β-caryophyllene with a new sesquiterpene synthase from tobacco

Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts (2022)

-

Biocatalytic production of the antibiotic aurachin D in Escherichia coli

AMB Express (2022)

-

Identification of the sesquiterpene synthase AcTPS1 and high production of (–)-germacrene D in metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Microbial Cell Factories (2022)

-

Precursor prioritization for p-cymene production through synergistic integration of biology and chemistry

Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.