Abstract

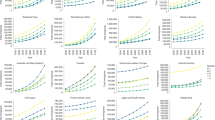

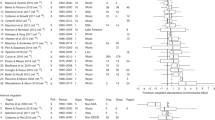

Climate change impacts may drive affected populations to migrate. However, migration decisions in response to climate change could have broader effects on population dynamics in affected regions. Here, I model the effect of climate change on fertility rates, income inequality, and human capital accumulation in developing countries, focusing on the instrumental role of migration as a key adaptation mechanism. In particular, I investigate how climate-induced migration in developing countries will affect those who do not migrate. I find that holding all else constant, climate change raises the return on acquiring skills, because skilled individuals have greater migration opportunities than unskilled individuals. In response to this change in incentives, parents may choose to invest more in education and have fewer children. This may ultimately reduce local income inequality, partially offsetting some of the damages of climate change for low-income individuals who do not migrate.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Black, R., Arnell, N. W., Adger, W. N., Thomas, D. & Geddes, A. Migration, immobility and displacement outcomes following extreme events. Environ. Sci. Policy 27, S32–S43 (2013).

Hino, M., Field, C. B. & Mach, K. J. Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 364–370 (2017).

Hauer, M. E. Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 321–325 (2017).

Shayegh, S., Moreno-Cruz, J. & Caldeira, K. Adapting to rates versus amounts of climate change: a case of adaptation to sea-level rise. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 104007 (2016).

IPCC Climate Change 2014–Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Black, R., Bennett, S. R., Thomas, S. M. & Beddington, J. R. Climate change: migration as adaptation. Nature 478, 447–449 (2011).

Black, R., Kniveton, D. & Schmidt-Verkerk, K. Disentangling Migration and Climate Change 29–53 (Springer, 2013).

McLeman, R. A. Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Raupach, M. R. et al. Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10288–10293 (2007).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. Demographic change and carbon dioxide emissions. Lancet 380, 157–164 (2012).

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K. & Norton, R. M. Environmental dimensions of migration. Annu. Rev. Soc. 41, 377–397 (2015).

Becker, G. S. Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries 209–240 (Columbia Univ. Press, 1960).

Galor, O. Unified Growth Theory (Princeton Univ. Press, 2011).

Bleakley, H. & Lange, F. Chronic disease burden and the interaction of education, fertility, and growth. Rev. Econ. Statist. 91, 52–65 (2009).

Aaronson, D., Lange, F. & Mazumder, B. Fertility transitions along the extensive and intensive margins. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 3701–3724 (2014).

Fernihough, A. Human capital and the quantity–quality trade-off during the demographic transition. J. Econ. Growth 22, 35–65 (2017).

Easterlin, R. A. An economic framework for fertility analysis. Stud. Family Plan. 6, 54–63 (1975).

Bongaarts, J. The supply-demand framework for the determinants of fertility: an alternative implementation. Popul. Stud. 47, 437–456 (1993).

Beine, M. & Parsons, C. Climatic factors as determinants of international migration. Scand. J. Econ. 117, 723–767 (2015).

Gröschl, J. & Steinwachs, T. Do natural hazards cause international migration? CESifo Econ. Stud. Working Paper No. 6145 (2016).

Cattaneo, C. & Peri, G. The migration response to increasing temperatures. J. Dev. Econ. 122, 127–146 (2016).

Adger, W. N. et al. Focus on environmental risks and migration: causes and consequences. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 060201 (2015).

Beine, M., Docquier, F. & Rapoport, H. Brain drain and economic growth: theory and evidence. J. Dev. Econ. 64, 275–289 (2001).

Beine, M., Docquier, F. & Rapoport, H. Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: winners and losers. Econ. J. 118, 631–652 (2008).

Deschenes, O. Temperature, human health, and adaptation: a review of the empirical literature. Energy Econ. 46, 606–619 (2014).

Barreca, A., Deschenes, O. & Guldi, M. Maybe next month? temperature shocks, climate change, and dynamic adjustments in birth rates. NBER Working Paper (NBER, 2015).

Desmet, K. & Rossi-Hansberg, E. On the spatial economic impact of global warming. J. Urban Econ. 88, 16–37 (2015).

Altonji, J. G. & Card, D. Immigration, Trade, and the Labor Market 201–234 (Univ. Chicago Press, 1991).

Card, D. Immigration and Inequality Tech. Rep. (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009).

Xu, P., Garand, J. C. & Zhu, L. Imported inequality? Immigration and income inequality in the american states. State Polit. Policy Quart. 16, 147–171 (2016).

Weyl, E. G. The openness-equality trade-off in global redistribution. Econ. J. (in the press).

Obokata, R., Veronis, L. & McLeman, R. Empirical research on international environmental migration: a systematic review. Popul. Environ. 36, 111–135 (2014).

Findlay, A. M. Migrant destinations in an era of environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 21, S50–S58 (2011).

Nordhaus, W. D. & Boyer, J. Warming the World: Economic Models of Global Warming (MIT, 2003).

Golosov, M., Hassler, J., Krusell, P. & Tsyvinski, A. Optimal taxes on fossil fuel in general equilibrium. Econometrica 82, 41–88 (2014).

Jones, C. I. & Romer, P. M. The new Kaldor facts: ideas, institutions, population, and human capital. Am. Econ. J. 2, 224–245 (2010).

Diamond, P. A. National debt in a neoclassical growth model. Am. Econ. Rev. 55, 1126–1150 (1965).

Caselli, F. & Coleman, W. J. The US structural transformation and regional convergence: a reinterpretation. J. Polit. Econ. 109, 584–616 (2001).

Gollin, D., Lagakos, D. & Waugh, M. E. The agricultural productivity gap. Quart. J. Econ. 129, 939–993 (2014).

Van Vuuren, D. P. et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Climatic Change 109, 5–31 (2011).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Climatic Change 109, 213–241 (2011).

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M. & Hsiang, S. M. Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9780–9785 (2014).

Moss, R. H. et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010).

Acemoglu, D. Directed technical change. Rev. Econ. Stud. 69, 781–809 (2002).

Lutz, W., Butz, W. P. & Samir, K. World Population and Human Capital in the Twenty-First Century (OUP Oxford, 2014).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank G. P. Casey from Brown University for assistance with developing the analytical model and for comments that greatly improved the manuscript. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 703399 for the project ‘Robust Policy’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 954 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shayegh, S. Outward migration may alter population dynamics and income inequality. Nature Clim Change 7, 828–832 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3420

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3420

This article is cited by

-

Identifying key processes and sectors in the interaction between climate and socio-economic systems: a review toward integrating Earth–human systems

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2021)

-

Random forest analysis of two household surveys can identify important predictors of migration in Bangladesh

Journal of Computational Social Science (2021)

-

The economic interaction between climate change mitigation, climate migration and poverty

Nature Climate Change (2020)