Abstract

The Archaea occupy a key position in the Tree of Life, and are a major fraction of microbial diversity. Abundant in soils, ocean sediments and the water column, they have crucial roles in processes mediating global carbon and nutrient fluxes. Moreover, they represent an important component of the human microbiome, where their role in health and disease is still unclear. The development of culture-independent sequencing techniques has provided unprecedented access to genomic data from a large number of so far inaccessible archaeal lineages. This is revolutionizing our view of the diversity and metabolic potential of the Archaea in a wide variety of environments, an important step toward understanding their ecological role. The archaeal tree is being rapidly filled up with new branches constituting phyla, classes and orders, generating novel challenges for high-rank systematics, and providing key information for dissecting the origin of this domain, the evolutionary trajectories that have shaped its current diversity, and its relationships with Bacteria and Eukarya. The present picture is that of a huge diversity of the Archaea, which we are only starting to explore.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Following the first report of the wide distribution of archaeal lineages in the marine environment (DeLong, 1992), a commentary by Gary Olsen stated enthusiastically: ‘…overlooking the Archaea has been equivalent to surveying one square kilometre of the African savanna and missing over 300 elephants’ (Olsen, 1994). Today, this analogy has been largely verified, and the initial expectations have even been exceeded. A burst in the availability of the first genomic data from a large number of uncultured archaeal lineages has been witnessed in the past few years. According to the NCBI genome database, 1062 archaeal genomes have been made available as of December 2016 (Figure 1), of which 186 are from metagenomes and 111 are single cell genomes. Twice as many are sequenced but not yet released according to the GOLD database. Given that the symbolic number of 100 complete genomes was reached only six years ago (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011), this provides a measure of how rapidly the field of archaeal genomics is moving. As a comparison, the number of isolates and newly described species has remained stationary (Figure 1), and mainly concerns members of well-characterized lineages, stressing the need for a stronger isolation effort. To that end, metabolic predictions derived from genomic data of uncultured archaeal lineages can also provide unprecedented information to guide culture strategies.

Number of archaeal genome sequences and validly described archaeal species over the last 20 years. The orange line and histogram indicate respectively the annual and cumulative number of novel archaeal genome sequences (that is, complete genomes, chromosome, contigs and scaffolds) released in public databases (NCBI, latest update December 2016). The blue line and histogram indicate respectively the annual and cumulative number of validly described archaeal species (Source: List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature with names published until July 2016—http://www.bacterio.net/).

The analysis of the first genomic data from these newly sequenced lineages has had a strong impact on archaeal systematics, leading to the proposal of a multitude of new clades at various taxonomic levels (orders, classes, phyla, superclasses, superphyla), with a wealth of new assigned names that have replaced the original acronyms from environmental 16S rRNA studies (Table 1). It is important to remember here that there is no established criterion to propose a new taxonomic status above the Class level, an important priority to address in modern microbial systematics (Gribaldo and Brochier-Armanet, 2012). Moreover, the phylogenetic coherence of already established high-rank systematics in both Bacteria and Archaea based on 16S rDNA divergence is far from uniform (Yarza et al., 2014). The current and future deluge of genomic sequences from an ever-larger fraction of uncultured microbial diversity prompts for the urgent establishment of common criteria based on genomic data, particularly in the frame of nomenclature and classification consistency of major reference databases.

Under such a deluge of genomic data, the establishment of a robust phylogenetic frame for the Archaea, and, in particular, the placement of all the new uncultured lineages, becomes of paramount importance. This is essential to infer the nature of the last ancestor of Archaea and the very origin of this domain of life, as well as its relationship with eukaryotes. Also, it allows understanding the evolutionary processes that led to present-day archaeal diversity and drove the emergence of specific metabolic capacities and adaptations to different environments, well beyond extreme niches.

The majority of the new genomes originate from uncultured lineages representing a sizeable proportion of microbial life in sediments and water columns, and may significantly increase the already well-recognized importance of Archaea as major players in global biogeochemical cycles (Offre et al., 2013). Thus, access to genomic data and the associated metabolic potential of the first representatives of these lineages is an important step toward understanding their role in the environment, and provides a new outlook on the metabolic diversity of the Archaea (Table 2).

Hereafter, we will present an overview of some of the most significant recent findings, which are discussed based on an updated robust phylogeny of the Archaea obtained from a large taxonomic sampling including all the new uncultured lineages (Figure 2). The fast-evolving nanosized lineages constituting the proposed DPANN superphylum (Rinke et al., 2013) have been treated separately, because their monophyly and phylogenetic placement are unclear, and will be discussed in a dedicated section.

Phylogeny of the Archaea. Bayesian phylogeny (PhyloBayes, CAT+GTR+ Γ4) based on a 41 gene supermatrix (8710 amino acid positions). Scale bar represents the average number of substitutions per site. Node supports refer to posterior probabilities, and ultrafast bootstrap values based on a thousand replicates calculated by maximum likelihood (IQTree, LG+C60). The 41 genes consist of 36 genes from the Phylosift marker genes list (Darling et al., 2014), plus RNA polymerase subunits A and B, and three universal ribosomal proteins (L7-L12, L30, S4) from (Liu et al., 2012). The tree is rooted according to (Raymann et al., 2015), but alternative roots are indicated with numbered red dots (see main text for discussion). Grey font indicates the clades for which no isolates are available. Currently proposed taxonomic status: C=Class; P=Phylum; SC=Super Class; SP=Super Phylum.

The expanding TACK superphylum

The TACK superphylum was proposed in 2011 based on phylogenetic proximity and signatures shared with eukaryotes (Guy and Ettema, 2011). At that time, it included the Thaumarchaeota, the Aigarchaeota, the Crenarchaeota and the Korarchaeota (Guy and Ettema, 2011; Table 1). An additional TACK phylum named Geoarchaeota was suggested (Table 1; Kozubal et al., 2013), but was subsequently indicated to represent a deep-branching lineage of the Crenarchaeota (Guy et al., 2014; Table 1), consistently with our analysis (Figure 2). Based on a large-scale phylogenomic analysis it has been recently proposed that the TACK represents a kingdom-level clade named Proteoarchaeota (Petitjean et al., 2014). In recent years, the genomic coverage for members of the TACK has substantially increased, providing a better view on its diversity and evolution.

Thaumarchaeota and the origin of archaeal nitrification

For a long time, the phylum Thaumarchaeota (former Group I Crenarchaeota, Table 1) has been identified with the ecologically important aerobic ammonia oxidizing archaea inhabiting marine (Group I.1a/Nitrosopumilales, Nitrosopumilus, Nitrosoarchaeum, Cenarchaeum), and soil environments (Group I.1b/Nitrososphaerales, Nitrososphaera) (Pester et al., 2011). Increasing availability of genomic data from three new thaumarchaeal lineages (Figure 2) has drastically changed this picture and provided substantial insights into the still largely unexplored metabolic versatility of the Thaumarchaeota. These genomes correspond to Fn1 (Group I.1c) obtained from deep anoxic peat layers (Lin et al., 2015), and to Beowulf (Group I.1d) and Dragon (Group I.1d) obtained from acidic (pH ~3), thermophilic (65–72 °C), iron oxide and sulfur sediments of Yellowstone National Park (Beam et al., 2014; Table 2). Although Fn1 is predicted to obtain energy and carbon from β-oxidation of volatile fatty acids, either by using fumarate as terminal electron acceptor or in syntrophy with methanogens (Lin et al., 2015), both Beowulf and Dragon Thaumarchaeota appear to be versatile chemoorganotrophs, potentially growing on diverse carbohydrates, peptides and amino acids (Beam et al., 2014). Surprisingly, while mostly complete, none of the genomes from these three Thaumarchaeota lineages contains the amoABC genes for ammonia oxidation (Beam et al., 2014). This indicates that the ability to oxidize ammonia is not a general characteristic of the Thaumarchaeota. In this respect, further genomic data and exploration of the metabolic potential and phylogenetic placement of the three lineages, in particular Fn1, which appear to be the closest relatives of aerobic ammonia oxidizing archaea (Figure 2), will provide key information on the emergence of ammonia oxidation in the Thaumarchaeota.

Fn1, Beowulf and Dragon might also provide significant information on the adaptation of ammonia oxidizing Thaumarchaeota to aerobic conditions. Fn1 members were in fact isolated from anaerobic environments (Lin et al., 2015), Dragon members were obtained from hypoxic conditions, and have genes indicating the ability for elemental sulfur reduction (Beam et al., 2014), while Beowulf members were isolated from oxic conditions where they might use oxygen as terminal electron acceptor (as suggested by the presence of a Heme Copper Oxidase, HCO), but might also be capable of growing anaerobically by reducing nitrate to nitrite thanks to the presence of a narGHJI gene cluster (Beam et al., 2014).

Finally, the deep branching of Beowulf and Dragon lineages (Figure 2) may support the hypothesis of a thermophilic ancestor for all Thaumarchaeota and a subsequent adaptation to mesophilic environments (Barns et al., 1996; Eme et al., 2013), a trend becoming more and more evident for many archaeal phyla. Additional genomes and isolation of the first members of these lineages, combined with specific phylogenetic analyses will clarify the overall phylogeny of the Thaumarchaeota and allow further assumptions on the diversity and emergence of various metabolic capacities in this important phylum.

Aigarchaeota and adaptation to oxygen

Genomic coverage has also substantially expanded for the Aigarchaeota (former Hot Water Crenarchaeotic Group, HWCG I, Table 1), a diverse lineage widespread in moderate to extremely hot terrestrial, marine, and subsurface environments (Hedlund et al., 2015) which robustly branch as the sister clade of Thaumarchaeota (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011 and Figure 2). Obtained from a subsurface geothermal water stream, the metagenome of ‘Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum’ was the first to be published (Nunoura et al., 2011), and was followed by several SAGs from various hydrothermal environments (Rinke et al., 2013). Another candidate species named ‘Ca. Caldithenuis aerorheumensis’, from an oxic, hot spring streamer microbial community, has been the target of a metatranscriptomic analysis, providing the first insights into the metabolic potential of Aigarchaeota in situ (Beam et al., 2016). They appear as filamentous microorganisms that are capable of chemoorganoheterotrophy by using several organic carbon substrates (Table 2). Seemingly, Aigarchaeota are auxotrophs for vitamins and cofactors, as well as heme, which they might obtain from other community members (Beam et al., 2016).

The phylogenetic placement of Aigarchaeota makes them a key lineage to investigate the emergence of Thaumarchaeota and their specific metabolic adaptations. For example, the presence of an Heme Copper Oxidase, HCO, in the majority of available Aigarchaeota and Thaumarchaeota genomes indicates that the capacity to grow aerobically is a widespread trait of these lineages (Beam et al., 2016). This raises the question of whether adaptation to aerobic environments preceded the divergence of Aigarchaeota and Thaumarchaeota or instead it occurred independently in the two phyla.

Bathyarchaeota: key players in the global carbon cycle

The TACK superphylum has recently acquired a new member lineage, the Bathyarchaeota (former Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group, MCG, Table 1), an emerging clade of great ecological interest. Bathyarchaeota are robustly indicated as the sister lineage to the Aigarchaeota/Thaumarchaeota (Figure 2). This phylogenetic affiliation is also supported by the fact that many genomes of Bathyarchaeota contain homologues of the eukaryotic-like Topoisomerase IB (Meng et al., 2014), a character so far defining the Thaumarchaeota/Aigarchaeota (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011), pushing the origin of this enzyme further back in archaeal diversification than previously thought. The Bathyarchaeota are ubiquitous in both terrestrial and marine anoxic sediments (surface and subsurface) where they can represent a major fraction of the archaeal community (Kubo et al., 2012; Lloyd et al., 2013). The extensive diversity of this lineage, divided into as many as 17 subgroups (mostly at the family level), suggests a wide variety of metabolisms and environmental adaptations (Kubo et al., 2012). The genomic data now available for six subgroups has revealed a common capacity to degrade peptides to obtain carbon and energy, and a more variable ability to use carbohydrates, fatty acids or aromatic compounds (Lloyd et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2014; Evans et al., 2015; He et al., 2016; Lazar et al., 2016; Table 2). The utilization of a diverse range of organic compounds for heterotrophic growth is also supported by incorporation of 13C-labelled molecules (Seyler et al., 2014). In addition, several members of the phylum possess a complete H4MPT-type Wood-Ljungdahl (WL) pathway and genes for acetate formation suggesting the possibility of growing autotrophically by acetogenesis from H2+CO2, a capacity previously thought to be limited to Bacteria (He et al., 2016; Lazar et al., 2016). Moreover, some members possess markers of methanogenesis, suggesting a possible role in the methane cycle (Evans et al., 2015; see below). The potential metabolic flexibility between autotrophic and heterotrophic growth on a wide range of compounds represents an ecological advantage for the Bathyarchaeota and underlines the importance of this abundant benthic group in the global carbon cycle.

Lokiarchaeum, Asgard and the origin of eukaryotes

Among the major accomplishments of the exploration of uncultured archaeal diversity is the discovery of new lineages proposed to be the closest relatives of eukaryotes. The phylum Lokiarchaeota was defined following the sequencing of the first metagenomic data from the uncultured DSAG lineage (Spang et al., 2015, Table 1). De novo assembly and binning was applied on DNA extracted from deep marine sediment samples (3283 m below sea level) at the Arctic Mid-Ocean-Ridge, in the vicinities of the hydrothermal Loki’s Castle site (Jorgensen et al., 2012). This resulted in the reconstruction of one nearly complete (Lokiarchaeum) and two partial (Loki 2 and Loki3) genomes related to this lineage. These data revealed a surprisingly large number of eukaryotic signature proteins previously thought to be absent in Archaea, in particular genes coding for components related to membrane remodelling and cytoskeletal functions in eukaryotes (for example, actin, small Ras GTPases, extended ESCRT complex; Spang et al., 2015). Consistent with their genomic content, the inclusion of the three Lokiarchaeota in a universal tree of life indicated them as a sister clade to eukaryotes, suggesting that Lokiarchaeota may represent a ‘missing link’ between the two domains of life (Spang et al., 2015). Additional studies have been consistent with this hypothesis by analysing the Lokiarchaeum genome for homologues of a few eukaryotic-like processes, such as the membrane-trafficking system (Klinger et al., 2016) and the selenocysteine-encoding system (Mariotti et al., 2016).

Very recently, genomic sequences have been obtained from three additional uncultured phyla closely related to Lokiarchaeota (Table 1 and Figure 2): the Thorarchaeota, the Heimdallarchaeota and the Odinarchaeota (Seitz et al., 2016; Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al., 2017). The Thorarchaeota (former MBG-B) were described based on partial- to near-complete genomes obtained from sediments of the White Oak River estuary, in the sulfate–methane transition zone (Seitz et al., 2016). The Odinarchaeota, and the Heimdallarchaeota genomes were obtained from high-temperature habitats and marine sediments, respectively (Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al., 2017). Along with additional metagenomic bins of Lokiarchaeota and Thorarchaeota, they were shown to possess further eukaryotic signature proteins, such as eukaryotic-like tubulins, homologues of the ɛ DNA polymerase and membrane-trafficking components (TRAPP complex, Sec23/24 family proteins), and proposed to form a new superphylum which was named Asgard (Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al., 2017, Figure 2). Further evolutionary analysis of Asgard lineages might provide important information on the processes that led to the emergence of the first eukaryotic cell. To confirm and extend these results, isolation of the first representatives of Asgard members are paramount priorities.

Asgard lineages are common inhabitants of anaerobic marine, estuarine and lake sediments, and they might have an important role in the global carbon cycle (Table 2; Teske and Sørensen, 2008). Metabolic prediction suggests that Thorarchaeota are able to degrade organic matter, contributing to the carbon cycle, but also may have a role in intermediate sulfur cycling (Seitz et al., 2016). Based on the presence of an almost-complete H4MPT-type WL pathway and of some electron-bifurcating hydrogenases coding genes in its genome, it was proposed that Lokiarchaeum might be anaerobic, autotrophic and hydrogen-dependent (Sousa et al., 2016). More in depth genomic analyses and the isolation of representative members will be necessary to clarify further the metabolic potential of the Asgard superphylum.

Methanogens, methanogens everywhere!

Methanogenesis is an important and ancient metabolism that is specific to the Archaea (Thauer et al., 2008). For a long time, the known diversity of methanogens was known to fall into two large clades, which were called Class I methanogens (Methanococci, Methanopyri, Methanobacteria) and Class II methanogens (Methanomicrobia: Methanosarcinales and Methanomicrobiales) (Bapteste et al., 2005). These two clusters have been confirmed and enriched by new genomic data. In particular, the monophyly of Class I methanogens was supported by a large-scale phylogenomic analysis of the archaeal domain leading to the proposal of the superclass Methanomada (Table 1 and Figure 2; Petitjean et al., 2015). This additionally stabilized the oft-unclear placement of Methanopyri in the archaeal phylogeny as robustly branching with Methanobacteria, a relationship also supported by a shared derived character, the presence of pseudomurein in their cell walls (Albers and Meyer, 2011).

Concerning Class II methanogens/Methanomicrobia, they now firmly include two novel divisions: Methanocellales (former Rice Cluster I) and Methanoflorentaceae (former Rice Cluster II; Table 1), as well as the non-methanogenic Halobacteria (Figure 2). More specific analyses are, however, necessary to fully resolve the internal relationships of this clade, in particular, to clarify which lineage represents the closest outgroup to the Halobacteria, whose specific amino acid composition might be at the origin of incongruent placements in different published studies. This will be essential to understand the process of adaptation to a halophilic, aerobic and heterotrophic lifestyle from a methanogenic ancestor (Nelson-Sathi et al., 2015; Groussin et al., 2016). Given a possible common origin from a methanogenic ancestor, we propose uniting former Methanogens Class II with their closely related non-methanogenic lineages (Halobacteria, ANaerobic MEthanotrophic (ANME-1), Syntropharchaeales, Archaeoglobi) into a new superclass called Methanotecta (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Recently, important progresses have been done on the characterization of methanogenesis cofactors (Zheng et al., 2016; Moore et al., 2017), and enzymes (Wagner, 2016). Also, a novel pathway for utilization of methoxylated compounds (methoxydotrophic methanogenesis) has been discovered in a member of Methanosarcinales, with important implications for deep subsurface methanogenesis (Mayumi, 2016). In addition, the diversity of archaea capable of methanogenesis appears much larger than previously thought, and among the most exciting discoveries in the archaeal field is the identification of a large number of new lineages of methanogens.

Methanomassiliicoccales: from deep sediments to the human gut

The Methanomassiliicoccales (former Rumen Cluster C/Rice Cluster III, Table 1) are a novel order of methanogens present in various environments such as marine and lake sediments, sewers, soils and also animal digestive systems (insects, ruminants, humans; Dridi et al., 2012; Paul et al., 2012; Borrel et al., 2013; Söllinger et al., 2016; Raymann et al., 2017; Table 2). Importantly, they represent the second lineage of methanogens, other than the Methanobacteriales, to include members consistently adapted to the human gastrointestinal tract (Gaci et al., 2014). The analysis of the first genomes of Methanomassiliicoccales isolated/enriched from the human gastrointestinal tract showed that they are unrelated to any previously known Class I and Class II methanogens, but are rather affiliated to a large clade of non-methanogenic lineages (Borrel et al., 2013, 2014b).

In agreement with their placement, the Methanomassiliicoccales display unique characteristics, such as complete lack of genes coding for methanogenesis from H2+CO2 and the MTR complex, making them reliant on methyl-dependent hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in an energy-conservation process that is not completely resolved (Borrel et al., 2014b; Lang et al., 2015). Moreover, the Methanomassiliicoccales use specific methyltransferases that contain the rare 22nd proteinogenic amino acid pyrrolysine (Pyl), which is incorporated during translation by a sophisticated process involving a specific amber non-sense codon suppressor tRNA (Borrel et al., 2014a). This genetic code expansion is potentially handled by distinct mechanisms compared with the few other Pyl-containing bacteria and archaea, and even among different Methanomassiliicoccales (Borrel et al., 2014a, b).

The discovery of Methanomassiliicoccales underlines our still poor understanding of the diversity and role of archaeal methanogens in human health and disease, an important area of future research (for a recent review, see Gaci et al., 2014; Bang and Schmitz, 2015). Indeed, trimethylamine (TMA), which can be depleted into methane by Methanomassiliicoccales, is generated by the gut microbiota from nutrients and is further converted in the liver into the pro-atherogenic compound trimethylamine N-oxide (Brugère et al., 2014). Analyses of human-associated Methanomassiliicoccales have supported their role in trimethylamine utilization in the gut but also revealed that members of the two main clades of Methanomassiliicoccales have contrasting associations with subject health status and microbiota (Borrel et al., 2017). Many aspects of the biology of Methanomassiliicoccales remain largely unknown. For instance, there are currently no genomic data and no isolate/enrichment culture from the large diversity of environmental members. This will provide important information on the role of Methanomassiliicoccales in the environment and on the paths that led to their adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract.

Methyl-dependent methanogenesis: more widespread than previously thought

The type of methanogenesis present in Methanomassiliicoccales is not an isolated case and as been recently inferred in a number of uncultured lineages. The genome sequences from an uncultured novel methanogenic lineage, WSA2/Arc1 (Table 1) were acquired from a wastewater treatment bioreactor (Nobu et al., 2016; Table 2). Because WSA2/Arc1 did not appear to group with any of the previously known methanogens, it was proposed that they represent a new class, tentatively called ‘Ca. Methanofastidiosa’ (Nobu et al., 2016). This is consistent with our phylogenetic analysis (Figure 2), where Methanofastidiosa are robustly placed within a potential new superclass, the Acherontia (see below, Table 1). Interestingly, the metabolism inferred from these genomic data indicates absence of CO2-reducing or aceticlastic methanogenesis, similarly to Methanomassiiicoccales, and a potential specialization on methylated-thiol reduction with H2 (Nobu et al., 2016; Table 2).

Moreover, potential new lineages of methanogens have been reported for the first time within the TACK superphylum. Metagenomic analysis has highlighted the presence of methanogenesis markers (for example, McrA) in two members of the Bathyarchaeota, and it has been proposed that they may proceed through reduction of methyl compounds by H2, like the Methanomassiliicoccales (Evans et al., 2015). Genomic data from a second lineage of putative methanogens with a similar metabolism of reduction of methyl-compounds (methylamines, methanol and methylthiols) was obtained from various anaerobic environments (Table 2) and proposed to represent a new phylum, the Verstraetearchaeota (Vanwonterghem et al., 2016; Table 1), which robustly cluster with the Crenarchaeota (Figure 2). Interestingly, both Verstraetearchaeota and the potentially methanogenic Bathyarchaeota are predicted to be able to gain energy through metabolisms other than methanogenesis (for example, fermentation of peptides), an observation never reported for any previously known methanogens.

Beyond methanogenesis: variations on a theme

Experimental characterization of members of these novel putative methanogenic lineages is needed to clarify their role in methane cycling and more generally in carbon cycling. Indeed, enzymes traditionally considered as markers of methanogenesis (for example, MCR) can also be used for anaerobic methane oxidation in several ANME lineages (Timmers et al., 2017) and have even been shown to catalyse reactions that do not involve methane in two recently characterized strains of a new genus called ‘Ca. Syntrophoarchaeum’ (Laso-Pérez et al., 2016; Table 2). The two ‘Ca. Syntrophoarchaeum’ strains were enriched from gas-rich hydrothermal sediments. Their genomes contain MCR-like complexes that are likely used to activate butane toward butyl-CoM, and this intermediate is further metabolized into acetyl-CoA by β-oxidation and finally to CO2 through the methyl branch of the WL pathway (Laso-Pérez et al., 2016). To perform this novel anaerobic alkane-degradation pathway, the two ‘Ca. Syntrophoarchaeum’ strains are dependent on a syntrophic partner, the sulfate-reducing bacterium ‘Ca. Desulfofervidus auxilii’ (Laso-Pérez et al., 2016). Direct cell-to-cell electron transfer through nanowire and cytochromes may occur between ‘Ca. Desulfofervidus auxilii’ and ‘Ca. Syntrophoarchaeum’, similarly to what has been observed between ANME and sulfate-reducing bacteria (Wegener et al., 2015; McGlynn, 2017). The two ‘Ca. Syntrophoarchaeum’ are robustly placed as sister group to ANME-1 (proposed Methanophagales, Figure 2, Table 1), and we therefore propose that they represent a new order, the Syntropharchaeales (Table 1). This placement is important because it allows to break the branch leading to Methanophagales, so far represented by a single genome, and might clarify the evolutionary processes that led to loss and tinkering of methanogenesis (Borrel et al., 2016). Based on their phylogenetic proximity with Synthrophoarchaeales MCR homologues, it has been suggested that Bathyarchaeota MCR may be involved in a similar metabolism (Laso-Pérez et al., 2016), which will require experimental demonstration.

These new data provide a novel view on the diversity and evolution of methanogenesis and associated metabolisms (for a recent discussion see (Borrel et al., 2016)). In particular, they highlight the widespread distribution and the likely underestimated environmental importance of methyl-dependent hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, and question its potential antiquity (Borrel et al., 2016). In addition, they are consistent with the hypothesis of a methanogenic ancestor for the Archaea, and a scenario whereby multiple independent losses/tinkering of this metabolism occurred during archaeal diversification (Raymann et al., 2015), the details of which remain to be fully understood.

New emerging clades in the archaeal tree

The availability of genomic data from previously uncharacterized lineages has allowed identification of several interesting new clades.

The Diaforarchaea: a model clade to study adaptive processes in the Archaea

Following the availability of genomic data from previously uncharacterized lineages, the new superclass Diaforarchaea was recently proposed (Petitjean et al., 2015; Table 1). All Diaforarchaea members sequenced so far share two common characters: the lack of eukaryotic-like histones otherwise largely present in archaea and the fact that their 16S and 23S rRNA genes are not clustered in the genome (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011; Borrel et al., 2014b).

The Diaforarchaea currently contain at least six well-defined lineages (Figure 2). Other than the already-mentioned Methanomassiliicoccales, they include: the Thermoplasmatales, which include the only known examples of wall-less archaea and inhabit extreme acidic, hot, solfataric environments, and are important contributors to the release of toxic acid mine drainage into the environment (Baker and Banfield, 2003); the Deep sea Hydrothermal Vent Euryarchaeota group 2 (DHVE-2, Aciduliprofundum), making up 15% of the Archaea at hydrothermal vents, where they contribute to sulfur and iron cycling (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Reysenbach et al., 2006); the Marine Benthic Group D (MBG-D), a class-level lineage abundant in anoxic deep sediments (for which we suggest the name Izemarchaea, Table 1) that has a key role in the global carbon cycling through degradation of organic matter (Lloyd et al., 2013; Table 2); the Terrestrial Miscellaneous Euryarchaeotic Group (TMEG, Table 1), whose members are found in gold mines, freshwater, marine sediment and peat soils, where they degrade long-chain fatty acids and reduce organosulfate or sulfite, important for carbon re-mineralization (Teske, 2006; Teske and Sørensen, 2008; Lin et al., 2015; Table 2); and two class-level lineages corresponding to Marine Group II (MG-II, Thalassoarchaea, Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2015) and Marine Group III (MG-III, Li et al., 2015), for which we propose the name Pontarchaea (Table 1). Thalassoarchaea and Pontarchaea are abundant in oxygenated surface and deep marine waters, where they contribute to the oceanic carbon cycle by degrading extracellular proteins, carbohydrates and straight-chain lipids (Iverson et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). Some Thalassoarchaea occupying the shallow photic zone are also able to obtain energy from light by using proteorhodopsins, which were acquired via lateral gene transfer from marine Proteobacteria (Frigaard et al., 2006; Iverson et al., 2012). Formerly thought to be restricted to deeper waters, some Pontarchaea are now known to also be epipelagic photoheterotrophs (Haro-Moreno et al., 2017).

The wide range of lifestyles of the Diaforarchaea lineages and their specific genomic and cellular characteristics make them a great model to study the processes underlying archaeal evolution and adaptation to contrasted environments. These may include for example the transition between anoxic (methanogenic lineages) and oxic (marine lineages) environments, or the consequences of the loss of the cell wall (Themoplasmatales).

Thermococcales gain new friends

The Thermococcales are one of the main model organisms in the Archaea (Leigh et al., 2011). Although they had no close relatives in the archaeal tree for a long time, they now appear evolutionarily related to four uncultured lineages. These form two large clades, possibly at superclass-level, for which we propose the names Acherontia and Stygia (Table 1 and Figure 2).

The Acherontia include Thermococcales, the aforementioned Methanofastidiosa (WSA2/Arc1), and the recently sequenced Theionarchaea (former Z7ME43, Lazar et al., 2017, Table 1). Theionarchaea appear to be widespread in sediments, and possess the WL pathway of carbon fixation into acetyl-CoA which could enter the Krebs cycle, and are probably capable to degrade detrital proteins as well as fix nitrogen to ammonium (Table 2). They also harbour a sulfhydrogenase through which they might use sulfur or polysulfides as electron acceptors (Lazar et al., 2017).

The Stygia include the Hadesarchaea (former South African Gold Mine Euryarchaeotic Group, SAGMEG) and the MSBL-1 (Mediterranean Seafloor Brine Lake Group 1, for which we suggest the name Persephonarchaea, Table 1). Hadesarchaea metagenomes were recovered from hot spring sediments at the White Oak River estuary and Yellowstone National Park (Baker et al., 2016). Hadesarchaea are predicted to be heterotrophic and possess genes for sulphidogenesis and sulfide oxidation, as well as for CO oxidation coupled to nitrite reduction (Baker et al., 2016). Persephonarchaea genomes were obtained from deep anaerobic ocean brine lakes in the Red sea (Mwirichia et al., 2016). They can import and ferment sugars via the Embden-Meyerhof pathway, and possess gluconeogenesis and a Krebs cycle, but no oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. In addition, Persephonarchaea are able to assimilate sulfur and possibly to import and reduce nitrate (Mwirichia et al., 2016). Interestingly, both lineages of the Stygia seem to be able to fix carbon in unusual ways, by combining partial versions of carbon fixation pathways (reverse TCA, Calvin, WL cycles). So far, all these new members of the Stygia and Acherontia have been retrieved from anaerobic and mostly moderate temperature environments, and possess unusual metabolic capabilities (Table 2). Sequencing of new members as well as exploration of their lifestyle will shed light on their metabolic diversity and evolution, including the emergence of the hyperthermophilic and heterotrophic Thermococcales.

Although they are paraphyletic clades in our Bayesian tree (Figure 2), the Stygia and Acherontia appear monophyletic in ML trees (not shown), consistent with a recent universal phylogeny (Hug et al., 2016). The phylogenetic relationships between Stygia and Acherontia will need to be clarified by more specific analyses when new genomic data become available. In any case, the Stygia and Acherontia appear as the closest relatives to the TACK and Asgard superphyla (Figure 2), hence they might hold clues on the emergence of these clades and their special link to eukaryotes. Finally, according to alternative possible rootings of the archaeal phylogeny (see later), the Stygia and Acherontia might be among the deepest branches in the Archaea, and therefore able to provide key information on the origin and deep evolution of this domain.

The enigmatic Altiarchaeales

The Altiarchaeales (former SM1 Euryarchaeon, Table 1) are an uncultured lineage whose members predominate subsurface anaerobic cold groundwater environments, which was proposed to represent a novel archaeal order (Probst et al., 2014). Altiarchaeales are one of the rare cases of archaea with an outer cell membrane, and display unique grappling hooks appendices (‘hami’) and form near pure biofilms in these environments (for a recent review, see Probst and Moissl-Eichinger, 2015). Other than their unique cell envelopes and related structures, the Altiarchaeales are also interesting from a metabolic point of view. The first metagenomic data point in fact to the presence of a complete WL pathway, indicating that they are capable of autotrophic metabolism and may represent an important carbon dioxide sink in the subsurface (Probst et al., 2014; Table 2). Clarifying the placement of Altiarchaeales and their evolutionary relationship with the other archaeal lineages is therefore relevant to all inferences of the metabolic capabilities of the last archaeal ancestor, as well as the origin and evolution of the WL pathway in Archaea.

In early analyses, Altiarchaeales were associated to Methanococcales (Probst et al., 2014). According to the recently proposed new root of the Archaea (Raymann et al., 2015) and our updated analysis, they could represent one of the deepest archaeal branches, possibly at the class or even phylum level (Figure 2). However, due to their fast evolutionary rates, the placement of Altiarchaeales in the archaeal phylogeny should be taken with caution. Other analyses have also suggested that they may be clustered with the fast-evolving DPANN lineages (Bird et al., 2016; Hug et al., 2016), although this may be caused by a tree reconstruction artefact and needs to be confirmed by specific analysis (see below).

Key open questions in the phylogeny of Archaea

The DPANN superphylum: reality or artefact?

One of the most intriguing outcomes of the exploration of archaeal diversity has been the discovery of a large number of archaeal lineages that display extremely reduced cell sizes and genomes. Their 16S rRNA sequences are so divergent that for a long time they have escaped detection by PCR-based environmental surveys. Since the identification of the first nanosized archaeon, Nanoarchaeum equitans, which lives attached to the surface of its crenarchaeotal host (Ignicoccus hospitalis) in hyperthermophilic environments (Huber et al., 2002; Forterre et al., 2009), other similar small archaea have been found in a variety of different environments (Table 3 and references therein). They all display very fast evolution, a phenomenon commonly linked to extreme genome reduction, and lack the coding capacity for most amino acid biosynthetic pathways, indicating dependence on other microorganisms for survival.

It has been suggested that nanosized archaeal lineages form a monophyletic deep-branching clade representing a new superphylum named DPANN (for Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota; Rinke et al., 2013). Since then, four additional DPANN groups have been defined through environmental genomic sequencing: Micrarchaeota, DHVEG-6, Pacearchaeota and Woesearchaeota (Table 3 and references therein). These lineages are found in many different environments (including oxic and anoxic ones; Table 3). Moreover, Pacearchaota and Woesearchaeota, initially sequenced from anoxic environments, are also abundant components of surface waters of oligotrophic alpine lakes (Ortiz-Alvarez and Casamayor, 2016), indicating a wider range of environmental adaptations.

The current picture is that of a very large diversity of DPANN lineages, with at least seven well-supported clades (Figure 3). However, a key question is whether the DPANN constitute a monophyletic clade and where they branch in the archaeal phylogeny. The clustering and deep branching of fast-evolving lineages is in fact a well-known artefact of tree reconstruction called long branch-attraction (Philippe, 2000). Indeed, the monophyly of DPANN was not recovered by in depth phylogenomic analyses (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011; Petitjean et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015). These indicated, for instance, Nanoarchaeota as a sister lineage of Thermococcales, in agreement with previous results (Brochier et al., 2005), and Nanohaloarchaeota grouping with Halobacteria, also consistently with previous reports (Narasingarao et al., 2012; Petitjean et al., 2014), but this placement may also be the result of a bias in amino acid composition driven by similar adaptation of these two lineages to high salt environments. Parvarchaeota and Micrarchaeota have been shown to branch with the Diaforarchaea (Petitjean et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the placement of Parvarchaeota and Micrarchaeota is unstable and they also clustered with other fast-evolving lineages at different places in the archaeal phylogeny (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011; Raymann et al., 2014).

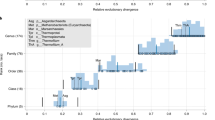

Diversity of the DPANN. Unrooted maximum likelihood phylogeny (IQTree, LG+C60) based on concatenation of the same 41 genes as in Figure 2 (9305 amino acid positions). Scale bar represents the average number of substitutions per site. Node supports refer to ultrafast bootstrap values based on a thousand replicates. The tree is only meant to describe the diversity of the DPANN, with at least seven well-supported clades. The question mark represents uncertainty on the relationships among these clades, as well as on the monophyly of the DPANN.

The distribution of archaeal characters in the DPANN might provide additional information to complement phylogenetic analysis (Figure 4). Evolutionary analysis of archaeal DNA replication components has highlighted the existence of a potential character shared between Nanohaloarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota and Parvarchaeota (but not Micrarchaeota): the presence of a peculiar DNA primase where the large and small subunits (PriS and PriL) are combined in a short version of the protein, distantly related to the classical archaeal enzyme (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011; Raymann et al., 2014). By searching all currently available DPANN genomes, we found that a fused primase appears to be a common feature of the large majority of DPANN lineages apart from Micrarchaeota and Diapherotrites, which possess a classical PriS+PriL primase (Figure 4). This might indicate that at least Micrarchaeota and Diapherotrites could be evolutionarily distinct from other DPANN lineages. However, the presence of a fused primase may also be due to evolutionary convergence for reduced genome sizes, or horizontal gene transfer among DPANN clades.

Distribution of marker genes in Archaea. Homologues were searched by Blast and HMM searches against a local database of 646 representative archaeal genomes (one per species). Alignment, phylogenetic analysis and examination of genomic synteny were performed to confirm homology when necessary. To account for the presence/absence of characters in very recent genomes added in public databases, we also checked by Blast on the NCBI. Full circles represent presence in most or all members of the taxon, empty circles absence and partial circles presence in a few members only. It should be noted, however, that absence of genes in uncultured taxa may be due to genomes incompleteness. For the ubiquitin system, we considered presence when at least two out of the three main components were found. For RNA polymerase beta and alpha genes, a single square means a fused gene and two squares a split gene. For primase, a single square means a unitary ‘fused’ primase, and two squares means the classical archaeal two subunit primase (PriS+PriL). Asterisks in the Asgard ESCRT system indicate that they are more similar to eukaryotic than archaeal homologues.

Clearly, the placement of fast-evolving nanosized lineages in the archaeal tree remains an important open issue and a future methodological challenge. Combined with the evidence of a similar phenomenon in Bacteria (Candidate Phyla Radiation; Brown et al., 2015; Hug et al., 2016), exciting avenues of research arise to understand the mechanisms (and potential convergences) that led to such extreme reduction of cell and genome sizes in nanosized lineages, to analyse the impact on fundamental cellular processes, and to obtain information on their largely unknown biology.

The root of the Archaea, the nature of the last archaeal common ancestor and the puzzling distribution of archaeal characters

Rooting the tree of a domain of life is a key issue, as it allows to polarize characters, to establish deep evolutionary relationships among the major phyla, to infer the nature of the ancestor and to propose high-rank systematics categories. The traditional root of the Archaea has been historically placed between Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota (Woese et al., 1990) and by extension the TACK (Figure 2, node #1). This root has also been supported by large-scale phylogenomic analyses, leading to a proposal for restructuring high-rank systematics of the Archaea with two major kingdoms, the Proteoarchaeota (TACK) and the Euryarchaeota (Petitjean et al., 2014). Nevertheless, by applying a sophisticated approach to uncover the ancient phylogenetic signal in proteins shared between Archaea and Bacteria, we have recently challenged this root. Support was found for a new root of the archaeal tree that falls within the Euryarchaeota, de facto breaking apart this phylum (Raymann et al., 2015; Figure 2, node #2). We suggested that the traditional root of the Archaea might be the result of an artefact linked to the presence of noisy phylogenetic signal in sequence data, important elements affecting deep phylogenies (Raymann et al., 2015). According to the new root, the first divergence in the Archaea would have separated two large clusters (Figure 2): Cluster I including Proteoarchaeota/TACK, Methanobacteriales, Methanococcales and Thermococcales, and Cluster II including all remaining ‘Euryarchaeota’ (Raymann et al., 2015). The inclusion of the new archaeal lineages described here extends greatly these two clusters (Figure 2).

The possibility of a new root lying within the Euryarchaeota opens up a new look on the origin and early evolution of the Archaea. For example, past inferences on the nature of the last archaeal common ancestor will have to be reconsidered. What used to be regarded as ‘euryarchaeal’ characters might be ancestral while the TACK ones would become derived. Furthermore, as both Cluster I and Cluster II include methanogenic lineages (Figure 2), the possibility arises that the last archaeal common ancestor itself was capable of methanogenesis, and that this metabolism was lost multiple times independently during archaeal evolution (Raymann et al., 2015). The large number of additional potential methanogenic lineages highlighted recently, including members of the TACK (Evans et al., 2015; Vanwonterghem et al., 2016), further supports this scenario (Borrel et al., 2016).

The new root is not at odds with current genomic data. The split between Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota for long supported by the distribution of specific characters has now become less sharp following their identification in other phyla (Brochier-Armanet et al., 2011; Eme and Doolittle, 2015; Figure 4). For instance, homologues of the cell division protein FtsZ, of eukaryotic-like histones H3/H4, and of DNA polymerase PolD, all characters previously considered as hallmarks of Euryarchaeota, are now evident in several lineages of the TACK superphylum (Figure 4), and can be inferred in the last archaeal common ancestor, regardless of where the root lies (Figure 2). Moreover, the distribution of these markers in the new divisions provides further interesting information on the diversity and evolution of fundamental cellular processes in the archaea; PolD appears to have been specifically lost in the ancestor of Crenarchaeota/Geoarchaeota, and FtsZ in the common ancestor of Verstraetearchaeota and Crenarchaeota/Geoarchaeota, possibly compensated for by the presence of crenactin or archaeal-like ESCRT systems for cell division (Figure 4).

In general, a search for the distribution of archaeal characters in all novel lineages reveals a much more complex pattern than previously thought. For example, complete eukaryotic-like ubiquitin systems, initially identified in one Aigarchaeota, appear to be present in all available Aigarchaeota, as well as most Asgard and Theionarchaea, and a few Methanomassiliicoccales and Izemarchaea (Figure 4). As already mentioned, homologues of TopoIB, for long indicated as a distinctive marker of Thaumarchaeota, are more widely distributed and scattered among various lineages. Homologues of bacterial type DNA gyrases (GyrA and B), in the past suggested as a possible marker of Cluster II archaea (Raymann et al., 2014), also appear to be more widely present in archaea. Finally, the pattern of split/fusion events in the genes coding for RNA polymerase A and B subunits appears much more complex than previously thought (Figure 4), and might be prone to evolutionary convergence (Brochier et al., 2004). It is expected that additional genomic data from a larger taxonomic sampling will even further complicate the picture. A more thorough analysis is needed to understand whether such puzzling distribution of characters that have key cellular roles reflects an ancient origin and multiple independent losses during archaeal diversification, or rather ancient horizontal gene transfers, or both, and if these events had an impact in the adaptation to different environments and lifestyles.

An important challenge ahead is to test the new root by including the new genomic data that were made available since our analysis. In particular, it will be essential to include the Altiarchaea, the Asgard and the Stygia, which occupy a pivotal position by lying in between the traditional and the new root, which may lead to an alternative root (Figure 2, unnumbered red dots). A robust analysis of the placement of the DPANN is also essential to the root issue. A number of recently published rooted archaeal phylogenies have shown the DPANN as the first emerging branch but with nonsignificant support (Rinke et al., 2013; Williams and Embley, 2014; Castelle et al., 2015; Hug et al., 2016). Still, as discussed above, the very fast evolutionary rates of the DPANN, which might lead to an artefactual monophyly, as well as their attraction at the base of the archaeal tree by the long branch of the bacterial outgroup, prompts for caution. For these reasons, previous analyses of the root of Archaea did not include DPANN lineages (Petitjean et al., 2014; Raymann et al., 2015). Promising alternative approaches are the use of sophisticated evolutionary models and new methodological improvements, such as those that enable to root phylogenies without the use of a bacterial outgroup, thus limiting the risk of tree reconstruction artefacts (Yang and Roberts, 1995; Szollosi et al., 2012, 2013; Groussin et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2015).

Perspectives

These are exciting times for archaeal research. Direct metagenomics approaches are likely to highlight an even higher diversity of archaeal lineages in the environment than currently known based on 16S rRNA surveys, as many commonly used primers may miss entire lineages (Eloe-Fadrosh et al., 2016). These data will give a better picture of the vast reservoir of metabolic capacities in the archaea, the way these emerged during their diversification, and their major ecological roles at the global scale. Yet, to confirm and extend ecological predictions based on sequences, it will be essential to put larger efforts in the isolation of representatives of uncultured lineages. This will also allow to refine genome completeness and annotations, and test a number of important evolutionary predictions currently based on genomes derived from metagenomes, notably the involvement of archaea in eukaryotic origins and the role of eukaryotic-like characters in an archaeal cellular context. Finally, it will open up the possibility to develop new experimental models in addition to the currently available ones, covering a larger representation of archaeal diversity. Combined with detailed evolutionary analyses, these data will continue to provide exciting insights into the fascinating archaeal biology.

Note added in proof

While this manuscript was in press, an analysis was published to determine the root of Archaea and the position of the DPANN (Williams et al., 2017). The authors employed a strategy which does not require the use of an outgroup, but is instead based on a probabilistic gene tree-species tree reconciliation approach taking into account gene family gain, duplication, transfer, and loss. By using a sampling of 62 archaeal genomes, they found that the root of the Archaea lies between a monophyletic DPANN clade and a group comprised of monophyletic Euryarchaeota and the TACK/Lokiarchaeum. However, the position of the different DPANN lineages was unstable when analyzed individually, suggesting that their grouping when analyzed together might be the result of an artefact. As discussed in this review, the monophyly of the DPANN needs to be tested further, and the root of Archaea to be analyzed by using a larger taxonomic sampling including key lineages (Altiarchaea, Stygia, and the new representatives of Acherontia and Asgard) that were not considered in the Williams et al. study.

References

Albers S-V, Meyer BH . (2011). The archaeal cell envelope. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 414–426.

Baker BJ, Banfield JF . (2003). Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 44: 139–152.

Baker BJ, Comolli LR, Dick GJ, Hauser LJ, Hyatt D, Dill BD et al. (2010). Enigmatic, ultrasmall uncultivated Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 8806–8811.

Baker BJ, Saw JH, Lind AE, Lazar CS, Hinrichs K, Teske AP et al. (2016). Genomic inference of the metabolism of cosmopolitan subsurface Archaea, Hadesarchaea. Nat Microbiol 1: 16002.

Bang C, Schmitz RA . (2015). Archaea associated with human surfaces: not to be underestimated. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39: 631–648.

Bapteste E, Brochier C, Boucher Y . (2005). Higher-level classification of the Archaea: evolution of methanogenesis and methanogens. Archaea 1: 353–363.

Barns SM, Delwiche CF, Palmer JD, Pace NR . (1996). Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9188–9193.

Beam JP, Jay ZJ, Kozubal MA, Inskeep WP . (2014). Niche specialization of novel Thaumarchaeota to oxic and hypoxic acidic geothermal springs of Yellowstone National Park. ISME J 8: 938–951.

Beam JP, Jay ZJ, Schmid MC, Rusch DB, Romine MF, Jennings M, De R et al. (2016). Ecophysiology of an uncultivated lineage of Aigarchaeota from an oxic, hot spring filamentous ‘streamer’ community. ISME J 10: 210–224.

Bird JT, Baker BJ, Probst AJ, Podar M, Lloyd KG . (2016). Culture independent genomic comparisons reveal environmental adaptations for Altiarchaeales. Front Microbiol 7: 1221.

Borrel G, Adam PS, Gribaldo S . (2016). Methanogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway: an ancient, versatile, and fragile association. Genome Biol Evol 8: evw114.

Borrel G, Gaci N, Peyret P, O’Toole PW, Gribaldo S, Brugère J-F . (2014a). Unique characteristics of the pyrrolysine system in the 7th order of methanogens: implications for the evolution of a genetic code expansion cassette. Archaea 2014: 374146.

Borrel G, McCann A, Deane J, Neto MC, Lynch DB, Brugère JF et al. (2017). Genomics and metagenomics of trimethylamine-utilizing Archaea in the human gut microbiome. ISME J; e-pub ahead of print 6 June 2017; doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.72.

Borrel G, O’Toole PW, Harris HMB, Peyret P, Brugère J-F, Gribaldo S . (2013). Phylogenomic data support a seventh order of methylotrophic methanogens and provide insights into the evolution of methanogenesis. Genome Biol Evol 5: 1769–1780.

Borrel G, Parisot N, Harris HMB, Peyretaillade E, Gaci N, Tottey W et al. (2014b). Comparative genomics highlights the unique biology of Methanomassiliicoccales, a Thermoplasmatales-related seventh order of methanogenic archaea that encodes pyrrolysine. BMC Genomics 15: 679.

Brochier C, Forterre P, Gribaldo S . (2004). Archaeal phylogeny based on proteins of the transcription and translation machineries: tackling the Methanopyrus kandleri paradox. Genome Biol 5: R17.

Brochier C, Gribaldo S, Zivanovic Y, Confalonieri F, Forterre P . (2005). Nanoarchaea: representatives of a novel archaeal phylum or a fast-evolving euryarchaeal lineage related to Thermococcales? Genome Biol 6: R42.

Brochier-Armanet C, Boussau B, Gribaldo S, Forterre P . (2008). Mesophilic Crenarchaeota: proposal for a third archaeal phylum, the Thaumarchaeota. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 245–252.

Brochier-Armanet C, Forterre P, Gribaldo S . (2011). Phylogeny and evolution of the Archaea: one hundred genomes later. Curr Opin Microbiol 14: 274–281.

Brown CT, Hug LA, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Castelle CJ, Singh A et al. (2015). Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 523: 208–211.

Brugère JF, Borrel G, Gaci N, Tottey W, O’Toole PW, Malpuech-Brugère C . (2014). Archaebiotics: proposed therapeutic use of archaea to prevent trimethylaminuria and cardiovascular disease. Gut Microbes 5: 5–10.

Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Hug LA, Brown CT, Wilkins MJ et al. (2015). Genomic expansion of domain archaea highlights roles for organisms from new phyla in anaerobic carbon cycling. Curr Biol 25: 690–701.

Darling AE, Jospin G, Lowe E, Matsen FA, Bik HM, Eisen JA . (2014). PhyloSift: phylogenetic analysis of genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ 2: e243.

DeLong EF . (1992). Archaea in coastal marine environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5685–5689.

Dridi B, Fardeau ML, Ollivier B, Raoult D, Drancourt M . (2012). Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62: 1902–1907.

Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Ivanova NN, Woyke T, Kyrpides NC . (2016). Metagenomics uncovers gaps in amplicon-based detection of microbial diversity. Nat Microbiol 1: 15032.

Eme L, Doolittle WF . (2015) Archaea. Curr Biol 25: R851–R855.

Eme L, Reigstad LJ, Spang A, Lanzén A, Weinmaier T, Rattei T et al. (2013). Metagenomics of kamchatkan hot spring filaments reveal two new major (hyper) thermophilic lineages related to thaumarchaeota. Res Microbiol 164: 425–438.

Evans PN, Parks DH, Chadwick GL, Robbins SJ, Orphan VJ, Golding SD et al. (2015). Methane metabolism in the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota revealed by genome-centric metagenomics. Science 350: 434–438.

Forterre P, Gribaldo S, Brochier-Armanet C . (2009). Happy together: genomic insights into the unique Nanoarchaeum/Ignicoccus association. J Biol 8: 7.

Frigaard N-UU, Martinez A, Mincer TJ, DeLong EF . (2006). Proteorhodopsin lateral gene transfer between marine planktonic Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 439: 847–850.

Gaci N, Borrel G, Tottey W, O’Toole PW, Brugère JF . (2014). Archaea and the human gut: new beginning of an old story. World J Gastroenterol 20: 16062–16078.

Gribaldo S, Brochier-Armanet C . (2012). Time for order in microbial systematics. Trends Microbiol 20: 209–210.

Groussin M, Boussau B, Gouy M . (2013). A branch-heterogeneous model of protein evolution for efficient inference of ancestral sequences. Syst Biol 62: 523–538.

Groussin M, Boussau B, Szöllõsi G, Eme L, Gouy M, Brochier-Armanet C et al. (2016). Gene acquisitions from bacteria at the origins of major archaeal clades are vastly overestimated. Mol Biol Evol 33: 305–310.

Guy L, Ettema TJG . (2011). The archaeal ‘TACK’ superphylum and the origin of eukaryotes. Trends Microbiol 19: 580–587.

Guy L, Spang A, Saw JH, Ettema TJG . (2014). ‘Geoarchaeote NAG1’ is a deeply rooting lineage of the archaeal order Thermoproteales rather than a new phylum. ISME J 8: 1–5.

Haro-Moreno JM, Rodriguez-Valera F, López-García P, Moreira D, Martin-Cuadrado A-B . (2017). New insights into marine group III Euryarchaeota, from dark to light. ISME J 11: 1102–1117.

He Y, Li M, Perumal V, Feng X, Fang J, Xie J et al. (2016). Genomic and enzymatic evidence for acetogenesis among multiple lineages of the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota widespread in marine sediments. Nat Microbiol 1: 16035.

Hedlund BP, Murugapiran SK, Alba TW, Levy A, Dodsworth JA, Goertz GB et al. (2015). Uncultivated thermophiles: current status and spotlight on ‘Aigarchaeota’. Curr Opin Microbiol 25: 136–145.

Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, Fuchs T, Wimmer VC, Stetter KO . (2002). A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature 417: 63–67.

Hug LA, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Probst AJ, Castelle CJ et al. (2016). A new view of the tree of life. Nat Microbiol 1: 16048.

Iino T, Tamaki H, Tamazawa S, Ueno Y, Ohkuma M, Suzuki KI et al. (2013). Candidatus Methanogranum caenicola: a novel methanogen from the anaerobic digested sludge, and proposal of Methanomassiliicoccaceae fam. nov. and Methanomassiliicoccales ord. nov., for a methanogenic lineage of the class Thermoplasmata. Microbes Environ 28: 244–250.

Iverson V, Morris RM, Frazar CD, Berthiaume CT, Morales RL, Armbrust EV . (2012). Untangling genomes from metagenomes: revealing an uncultured class of marine Euryarchaeota. Science 335: 587–590.

Jorgensen SL, Hannisdal B, Lanzen A, Baumberger T, Flesland K, Fonseca R et al. (2012). Correlating microbial community profiles with geochemical data in highly stratified sediments from the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E2846–E2855.

Klinger CM, Spang A, Dacks JB, Ettema TJG . (2016). Tracing the Archaeal origins of eukaryotic membrane-trafficking system building blocks. Mol Biol Evol 33: 1528–1541.

Kozubal MA, Romine M, Jennings R deM, Jay ZJ, Tringe SG, Rusch DB et al. (2013). Geoarchaeota: a new candidate phylum in the Archaea from high-temperature acidic iron mats in Yellowstone National Park. ISME J 7: 622–634.

Kubo K, Lloyd KG, F Biddle J, Amann R, Teske A, Knittel K . (2012). Archaea of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group are abundant, diverse and widespread in marine sediments. ISME J 6: 1949–1965.

Lang K, Schuldes J, Klingl A, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Brune A . (2015). New mode of energy metabolism in the seventh order of methanogens as revealed by comparative genome analysis of ‘Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum’. Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 1338–1352.

Laso-Pérez R, Wegener G, Knittel K, Widdel F, Harding KJ, Krukenberg V et al. (2016). Thermophilic archaea activate butane via alkyl-coenzyme M formation. Nature 539: 396–401.

Lazar CS, Baker BJ, Seitz K, Hyde AS, Dick GJ, Hinrichs KU et al. (2016). Genomic evidence for distinct carbon substrate preferences and ecological niches of Bathyarchaeota in estuarine sediments. Environ Microbiol 18: 1200–1211.

Lazar CS, Baker BJ, Seitz KW, Teske AP . (2017). Genomic reconstruction of multiple lineages of uncultured benthic archaea suggests distinct biogeochemical roles and ecological niches. ISME J 11: 1118–1129.

Leigh JA, Albers SV, Atomi H, Allers T . (2011). Model organisms for genetics in the domain Archaea: Methanogens, halophiles, Thermococcales and Sulfolobales. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35: 577–608.

Li M, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Jain S, Breier JA, Dick GJ . (2015). Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for scavenging of diverse organic compounds by widespread deep-sea archaea. Nat Commun 6: 8933.

Lin X, Handley KM, Gilbert JA, Kostka JE . (2015). Metabolic potential of fatty acid oxidation and anaerobic respiration by abundant members of Thaumarchaeota and Thermoplasmata in deep anoxic peat. ISME J 9: 2740–2744.

Liu Y-Y, Slotine J-J, Barabási A-L . (2012). Control centrality and hierarchical structure in complex networks Lespinet O (ed). PLoS One 7: e36972.

Lloyd KG, Schreiber L, Petersen DG, Kjeldsen KU, Lever MA, Steen AD et al. (2013). Predominant archaea in marine sediments degrade detrital proteins. Nature 496: 215–218.

Mariotti M, Lobanov A V, Manta B, Santesmasses D, Bofill A, Guigó R et al. (2016). Lokiarchaeota Marks the Transition between the Archaeal and Eukaryotic Selenocysteine Encoding Systems. Mol Biol Evol 33: 2441–2453.

Martin-Cuadrado A-B, Garcia-Heredia I, Moltó AG, López-Úbeda R, Kimes N, López-García P et al. (2015). A new class of marine Euryarchaeota group II from the mediterranean deep chlorophyll maximum. ISME J 9: 1619–1634.

Mayumi D . (2016). Methane production from coal by a single methanogen. Science (80-) 354: 222–225.

McGlynn SE . (2017). Energy metabolism during anaerobic methane oxidation in ANME Archaea. Microbes Environ 32: 5–13.

Meng J, Xu J, Qin D, He Y, Xiao X, Wang F . (2014). Genetic and functional properties of uncultivated MCG archaea assessed by metagenome and gene expression analyses. ISME J 8: 650–659.

Meyerdierks A, Kube M, Kostadinov I, Teeling H, Glöckner FO, Reinhardt R et al. (2010). Metagenome and mRNA expression analyses of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea of the ANME‐1 group. Environ Microbiol 12: 422–439.

Mondav R, Woodcroft BJ, Kim EH, McCalley CK, Hodgkins SB, Crill PM et al. (2014). Discovery of a novel methanogen prevalent in thawing permafrost. Nat Commun 5: 3212.

Moore SJ, Sowa ST, Schuchardt C, Deery E, Lawrence AD, Ramos JV et al. (2017). Elucidation of the biosynthesis of the methane catalyst coenzyme F430. Nature 543: 78–82.

Mwirichia R, Alam I, Rashid M, Vinu M, Ba-Alawi W, Anthony Kamau A et al. (2016). Metabolic traits of an uncultured archaeal lineage -MSBL1- from brine pools of the Red Sea. Sci Rep 6: 19181.

Narasingarao P, Podell S, Ugalde JA, Brochier-Armanet C, Emerson JB, Brocks JJ et al. (2012). De novo metagenomic assembly reveals abundant novel major lineage of Archaea in hypersaline microbial communities. ISME J 6: 81–93.

Nelson-Sathi S, Sousa FL, Roettger M, Lozada-Chávez N, Thiergart T, Janssen A et al. (2015). Origins of major archaeal clades correspond to gene acquisitions from bacteria. Nature 517: 77–80.

Nobu MK, Narihiro T, Kuroda K, Mei R, Liu WT . (2016). Chasing the elusive Euryarchaeota class WSA2: genomes reveal a uniquely fastidious methyl-reducing methanogen. ISME J 2: 1–10.

Nunoura T, Takaki Y, Kakuta J, Nishi S, Sugahara J, Kazama H et al. (2011). Insights into the evolution of Archaea and eukaryotic protein modifier systems revealed by the genome of a novel archaeal group. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 3204–3223.

Offre P, Spang A, Schleper C . (2013). Archaea in biogeochemical cycles. Annu Rev Microbiol 67: 437–457.

Olsen G . (1994). Archaea, Archaea, every where. Nature 371: 657–658.

Ortiz-Alvarez R, Casamayor EO . (2016). High occurrence of Pacearchaeota and Woesearchaeota (Archaea superphylum DPANN) in the surface waters of oligotrophic high-altitude lakes. Environ Microbiol Rep 8: 210–217.

Paul K, Nonoh JO, Mikulski L, Brune A . (2012). “Methanoplasmatales,” Thermoplasmatales-related archaea in termite guts and other environments, are the seventh order of methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 78 (23): 8245–8253.

Pester M, Schleper C, Wagner M . (2011). The Thaumarchaeota: an emerging view of their phylogeny and ecophysiology. Curr Opin Microbiol 14: 300–306.

Petitjean C, Deschamps P, López-Garciá P, Moreira D . (2014). Rooting the domain archaea by phylogenomic analysis supports the foundation of the new kingdom Proteoarchaeota. Genome Biol Evol 7: 191–204.

Petitjean C, Deschamps P, López-García P, Moreira D, Brochier-Armanet C . (2015). Extending the conserved phylogenetic core of archaea disentangles the evolution of the third domain of life. Mol Biol Evol 32: 1242–1254.

Philippe H . (2000). Opinion: long branch attraction and protist phylogeny. Protist 151: 307–316.

Probst AJ, Moissl-Eichinger C . (2015). ‘Altiarchaeales’: uncultivated archaea from the subsurface. Life (Basel) 5: 1381–1395.

Probst AJ, Weinmaier T, Raymann K, Perras A, Emerson JB, Rattei T et al. (2014). Biology of a widespread uncultivated archaeon that contributes to carbon fixation in the subsurface. Nat Commun 5: 5497.

Raymann K, Brochier-Armanet C, Gribaldo S . (2015). The two-domain tree of life is linked to a new root for the Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 6670–6675.

Raymann K, Forterre P, Brochier-Armanet C, Gribaldo S . (2014). Global phylogenomic analysis disentangles the complex evolutionary history of DNA replication in archaea. Genome Biol Evol 6: 192–212.

Raymann K, Moeller A, Goodman AL, Ochman H . (2017). Unexplored archaeal diversity in the great ape gut microbiome. mSphere 2: e00026–17.

Reysenbach A-L, Liu Y, Banta AB, Beveridge TJ, Kirshtein JD, Schouten S et al. (2006). A ubiquitous thermoacidophilic archaeon from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Nature 442: 444–447.

Rinke C, Schwientek P, Sczyrba A, Ivanova NN, Anderson IJ, Cheng J-F et al. (2013). Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature 499: 431–437.

Sakai S, Imachi H, Hanada S, Ohashi A, Harada H, Kamagata Y . (2008). Methanocella paludicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a methane-producing archaeon, the first isolate of the lineage ‘Rice Cluster I’, and proposal of the new archaeal order Methanocellales ord. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58: 929–936.

Seitz KW, Lazar CS, Hinrichs K-U, Teske AP, Baker BJ . (2016). Genomic reconstruction of a novel, deeply branched sediment archaeal phylum with pathways for acetogenesis and sulfur reduction. ISME J 10: 1696–1705.

Seyler LM, McGuinness LM, Kerkhof LJ . (2014). Crenarchaeal heterotrophy in salt marsh sediments. ISME J 8: 1534–1543.

Sousa FL, Neukirchen S, Allen JF, Lane N, Martin WF . (2016). Lokiarchaeon is hydrogen dependent. Nat Microbiol 1: 16034.

Spang A, Saw JH, Jørgensen SL, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Martijn J, Lind AE et al. (2015). Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature 521: 173–179.

Szollosi GJ, Boussau B, Abby SS, Tannier E, Daubin V . (2012). Phylogenetic modeling of lateral gene transfer reconstructs the pattern and relative timing of speciations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 17513–17518.

Szöllosi GJ, Tannier E, Lartillot N, Daubin V . (2013). Lateral gene transfer from the dead. Syst Biol 62: 386–397.

Söllinger A, Schwab C, Weinmaier T, Loy A, Tveit AT, Schleper C et al. (2016). Phylogenetic and genomic analysis of Methanomassiliicoccales in wetlands and animal intestinal tracts reveals clade-specific habitat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 92: fiv149.

Takai K, Horikoshi K . (1999). Genetic diversity of archaea in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. Genetics 152: 1285–1297.

Teske A, Sørensen KB . (2008). Uncultured archaea in deep marine subsurface sediments: have we caught them all? ISME J 2: 3–18.

Teske AP . (2006). Microbial communities of deep marine subsurface sediments: molecular and cultivation surveys. Geomicrobiol J 23: 357–368.

Thauer RK, Kaster A-K, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R . (2008). Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 579–591.

Timmers PHA, Welte CU, Koehorst JJ, Plugge CM, Jetten MSM, Stams AJM . (2017). Reverse methanogenesis and respiration in methanotrophic Archaea. Archaea 2017: 1654237.

Vanwonterghem I, Evans PN, Parks DH, Jensen PD, Woodcroft BJ, Hugenholtz P et al. (2016). Methylotrophic methanogenesis discovered in the novel archaeal phylum. Submitt Publ Nat 1: 16170.

Wagner T . (2016). The methanogenic CO2 reducing-and-fixing enzyme is bifunctional and contains 46 [4Fe-4S] clusters. Science 354: 114–117.

Wegener G, Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Tegetmeyer HE, Boetius A . (2015). Intercellular wiring enables electron transfer between methanotrophic archaea and bacteria. Nature 526: 587–590.

Williams TA, Embley TM . (2014). Archaeal ‘dark matter’ and the origin of eukaryotes. Genome Biol Evol 6: 474–481.

Williams TA, Heaps SE, Cherlin S, Nye TMW, Boys RJ, Embley TM . (2015). New substitution models for rooting phylogenetic trees. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370: 20140336.

Williams TA, Szöllősi GJ, Spang A, Foster PG, Heaps SE, Boussau B et al (2017). Integrative modeling of gene and genome evolution roots the archaeal tree of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E4602–E4611.

Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML . (1990). Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 4576–4579.

Yang Z, Roberts D . (1995). On the use of nucleic acid sequences to infer early branchings in the tree of life. Mol Biol Evol 12: 451–458.

Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Glöckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H et al. (2014). Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol 12: 635–645.

Zheng K, Ngo PD, Owens VL, Yang X, Mansoorabadi SO . (2016). The biosynthetic pathway of coenzyme F430 in methanogenic and methanotrophic archaea. Science 354: 339–342.

Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Caceres EF, Saw JH, Bäckström D, Juzokaite L, Vancaester E et al. (2017). Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature 541: 353–358.

Acknowledgements

PSA is supported by a PhD fellowship from Paris Diderot University and funds by the PhD Programme ‘Frontières du Vivant (FdV) – Programme Bettencourt’. GB is a recipient of a Roux-Cantarini fellowship from the Institut Pasteur. SG and CB-A acknowledge funding by the French National Agency for Research (ANR) grant ArchEvol (ANR-16-CE02-0005-01). We thank the three anonymous reviewers for very useful comments and suggestions. Finally, we apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space limitations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, P., Borrel, G., Brochier-Armanet, C. et al. The growing tree of Archaea: new perspectives on their diversity, evolution and ecology. ISME J 11, 2407–2425 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.122

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.122

This article is cited by

-

Elevated methane flux in a tropical peatland post-fire is linked to depth-dependent changes in peat microbiome assembly

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2024)

-

Human associated Archaea: a neglected microbiome worth investigating

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2024)

-

Rice developmental stages modulate rhizosphere bacteria and archaea co-occurrence and sensitivity to long-term inorganic fertilization in a West African Sahelian agro-ecosystem

Environmental Microbiome (2023)

-

Ultra-small bacteria and archaea exhibit genetic flexibility towards groundwater oxygen content, and adaptations for attached or planktonic lifestyles

ISME Communications (2023)

-

Diversity and function of methyl-coenzyme M reductase-encoding archaea in Yellowstone hot springs revealed by metagenomics and mesocosm experiments

ISME Communications (2023)