Spillover events, in which a pathogen that originates in animals jumps into people, have probably triggered every viral pandemic that’s occurred since the start of the twentieth century1. What’s more, an August 2021 analysis of disease outbreaks over the past four centuries indicates that the yearly probability of pandemics could increase several-fold in the coming decades, largely because of human-induced environmental changes2.

Fortunately, for around US$20 billion per year, the likelihood of spillover could be greatly reduced3. This is the amount needed to halve global deforestation in hotspots for emerging infectious diseases; drastically curtail and regulate trade in wildlife; and greatly improve the ability to detect and control infectious diseases in farmed animals.

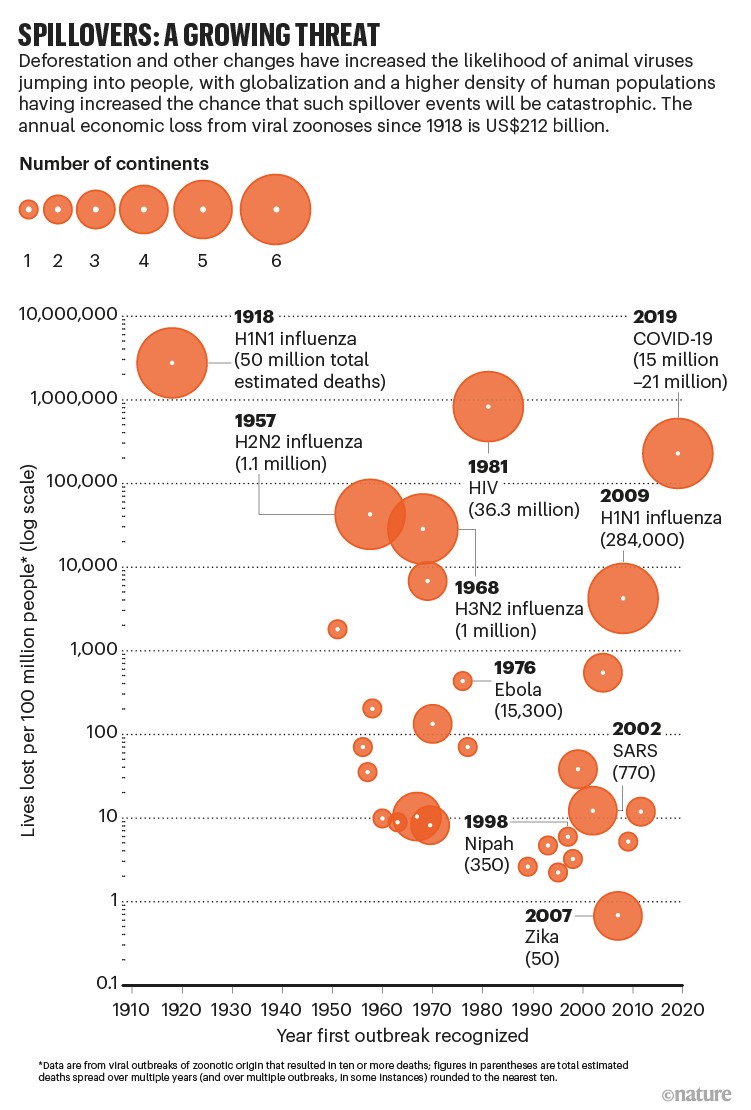

That is a small investment compared with the millions of lives lost and trillions of dollars spent in the COVID-19 pandemic. The cost is also one-twentieth of the statistical value of the lives lost each year to viral diseases that have spilled over from animals since 1918 (see ‘Spillovers: a growing threat’), and less than one-tenth of the economic productivity erased per year1.

Source: Ref. 1

Yet many of the international efforts to better defend the world from future outbreaks, prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, still fail to prioritize the prevention of spillover. Take, for example, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, established by the World Health Organization (WHO). The panel was convened in September 2020, in part to ensure that any future infectious-disease outbreak does not become another pandemic. In its 86-page report released last May, wildlife is mentioned twice; deforestation once.

We urge the decision-makers currently developing three landmark international endeavours to make the prevention of spillover central to each.

First, the G20 group of the world’s 20 largest economies provisionally agreed last month to create a global fund for pandemics. If realized, this could provide funding at levels that infectious-disease experts have been recommending for decades — around $5 per person per year globally (see go.nature.com/3yjitwx). Second, an agreement to improve global approaches to pandemics is under discussion by the World Health Assembly (WHA), the decision-making body of the WHO. Third, a draft framework for biodiversity conservation — the post-2020 global biodiversity framework — is being negotiated by parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Designed in the right way, these three international endeavours could foster a more proactive global approach to infectious diseases. This opportunity — to finally address the factors that drive major disease outbreaks, many of which also contribute to climate change and biodiversity loss — might not present itself again until the world faces another pandemic.

Four actions

The risk of spillover is greater when there are more opportunities for animals and humans to make contact, for instance in the trade of wildlife, in animal farming or when forests are cleared for mining, farming or roads. It is also more likely to happen under conditions that increase the likelihood of infected animals shedding viruses – when they are housed in cramped conditions, say, or not fed properly.

Decades of research from epidemiology, ecology and genetics suggest that an effective global strategy to reduce the risk of spillover should focus on four actions1,3.

First, tropical and subtropical forests must be protected. Various studies show that changes in the way land is used, particularly tropical and subtropical forests, might be the largest driver of emerging infectious diseases of zoonotic origin globally4. Wildlife that survives forest clearance or degradation tends to include species that can live alongside people, and that often host pathogens capable of infecting humans5. For example, in Bangladesh, bats that carry Nipah virus — which can kill 40–75% of people infected — now roost in areas of high human population density because their forest habitat has been almost entirely cleared6.

Furthermore, the loss of forests is driving climate change. This could in itself aid spillover by pushing animals, such as bats, out of regions that have become inhospitable and into areas where many people live7.

Yet forests can be protected even while agricultural productivity is increased — as long as there is enough political will and resources8. This was demonstrated by the 70% reduction in deforestation in the Amazon during 2004–12, largely through better monitoring, law enforcement and the provision of financial incentives to farmers. (Deforestation rates began increasing in 2013 due to changes in environmental legislation, and have risen sharply since 2019 during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency.)

Second, commercial markets and trade of live wild animals that pose a public-health risk must be banned or strictly regulated, both domestically and internationally.

Doing this would be consistent with the call made by the WHO and other organizations in 2021 for countries to temporarily suspend the trade in live caught wild mammals, and to close sections of markets selling such animals. Several countries have already acted along these lines. In China, the trade and consumption of most terrestrial wildlife has been banned in response to COVID-19. Similarly, Gabon has prohibited the sale of certain mammal species as food in markets.

A worker in a crowded chicken farm in Anhui province, China.Credit: Jianan Yu/Reuters

Restrictions on urban and peri-urban commercial markets and trade must not infringe on the rights and needs of Indigenous peoples and local communities, who often rely on wildlife for food security, livelihoods and cultural practices. There are already different rules for hunting depending on the community in many countries, including Brazil, Canada and the United States.

Third, biosecurity must be improved when dealing with farmed animals. Among other measures, this could be achieved through better veterinary care, enhanced surveillance for animal disease, improvements to feeding and housing animals, and quarantines to limit pathogen spread.

Poor health among farmed animals increases their risk of becoming infected with pathogens — and of spreading them. And nearly 80% of livestock pathogens can infect multiple host species, including wildlife and humans9.

Fourth, particularly in hotspots for the emergence of infectious diseases, people’s health and economic security should be improved.

People in poor health — such as those who have malnutrition or uncontrolled HIV infection — can be more susceptible to zoonotic pathogens. And, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals such as these, pathogens can mutate before being passed on to others10.

What’s more, some communities — especially those in rural areas — use natural resources to produce commodities or generate income in a way that brings them into contact with wildlife or wildlife by-products. In Bangladesh, for example, date palm sap, which is consumed as a drink in various forms, is often collected in pots attached to palm trees. These can become contaminated with bodily substances from bats. A 2016 investigation linked this practice to 14 Nipah virus infections in humans that caused 8 deaths11.

Providing communities with both education and tools to reduce the risk of harm is crucial. Tools can be something as simple as pot covers to prevent contamination of date palm sap, in the case of the Bangladesh example.

In fact, providing educational opportunities alongside health-care services and training in alternative livelihood skills, such as organic agriculture, can help both people and the environment. For instance, the non-governmental organization Health in Harmony in Portland, Oregon, has invested in community-designed interventions in Indonesian Borneo. During 2007–17, these contributed to a 90% reduction in the number of households that were reliant on illegal logging for their main livelihood. This, in turn, reduced local rainforest loss by 70%. Infant mortality also fell by 67% in the programme’s catchment area12.

Systems-oriented interventions of this type need to be better understood, and the most effective ones scaled up.

Wise investment

Such strategies to prevent spillover would reduce our dependence on containment measures, such as human disease surveillance, contact tracing, lockdowns, vaccines and therapeutics. These interventions are crucial, but are often expensive and implemented too late — in short, they are insufficient when used alone to deal with emerging infectious diseases.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the real-world limitations of these reactive measures — particularly in an age of disinformation and rising populism. For example, despite the US federal government spending more than $3.7 trillion on its pandemic response as of the end of March, nearly one million people in the United States — or around one in 330 — have died from COVID-19 (see go.nature.com/39jtdfh and go.nature.com/38urqvc). Globally, between 15 million and 21 million lives are estimated to have been lost during the COVID-19 pandemic beyond what would be expected under non-pandemic conditions (known as excess deaths; see Nature https://doi.org/htd6; 2022). And a 2021 model indicates that, by 2025, $157 billion will have been spent on COVID-19 vaccines alone (see go.nature.com/3jqds76).

A farmer in Myanmar gathers sap from a palm tree to make wine. Contamination of the collection pots with excretions from bats can spread diseases to humans.Credit: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty

Preventing spillover also protects people, domesticated animals and wildlife in the places that can least afford harm — making it more equitable than containment. For example, almost 18 months since COVID-19 vaccines first became publicly available, only 21% of the total population of Africa has received at least one dose. In the United States and Canada, the figure is nearly 80% (see go.nature.com/3vrdpfo). Meanwhile, Pfizer’s total drug sales rose from $43 billion in 2020 to $72 billion in 2021, largely because of the company’s COVID-19 vaccine, the best-selling drug of 202113.

Lastly, unlike containment measures, actions to prevent spillover also help to stop spillback, in which zoonotic pathogens move back from humans to animals and then jump again into people. Selection pressures can differ across species, making such jumps a potential source of new variants that can evade existing immunity. Some researchers have suggested that spillback was possibly responsible for the emergence of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 (see Nature 602, 26–28; 2022).

Seize the day

Over the past year, the administration of US President Joe Biden and two international panels (one established in 2020 by the WHO and the other in 2021 by the G20) have released guidance on how to improve approaches to pandemics. All recommendations released so far acknowledge spillover as the predominant cause of emerging infectious diseases. None adequately discusses how that risk might be mitigated. Likewise, a PubMed search for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 yields thousands of papers, yet only a handful of studies investigate coronavirus dynamics in bats, from which SARS-CoV-2 is likely to have originated14.

Spillover prevention is probably being overlooked for several reasons. Upstream animal and environmental sources of pathogens might be being neglected by biomedical researchers and their funders because they are part of complex systems — research into which does not tend to lead to tangible, profitable outputs. Also, most people working in public health and biomedical sciences have limited training in ecology, wildlife biology, conservation and anthropology.

Climate change will force new animal encounters — and boost viral outbreaks

There is growing recognition of the importance of cross-sectoral collaboration, including soaring advocacy for the ‘One Health’ approach — an integrated view of health that recognizes links between the environment, animals and humans. But, in general, this has yet to translate into action to prevent pandemics.

Another challenge is that it can take decades to realize the benefits of preventing spillover, instead of weeks or months for containment measures. Benefits can be harder to quantify for spillover prevention, no matter how much time passes, because, if measures are successful, no outbreak occurs. Prevention also runs counter to individual, societal and political tendencies to wait for a catastrophe before taking action.

The global pandemic fund, the WHA pandemic agreement and the post-2020 global biodiversity framework all present fresh chances to shift this mindset and put in place a coordinated global effort to reduce the risk of spillover alongside crucial pandemic preparedness efforts.

Global fund for pandemics

First and foremost, a global fund for pandemics will be key to ensuring that the wealth of evidence on spillover prevention is translated into action. Funding for spillover prevention should not be folded into existing conservation funds, nor draw on any other existing funding streams.

Investments must be targeted to those regions and practices where the risk of spillover is greatest, from southeast Asia and Central Africa to the Amazon Basin and beyond. Actions to prevent spillover in these areas, particularly by reducing deforestation, would also help to mitigate climate change and reduce loss of biodiversity. But conservation is itself drastically underfunded. As an example, natural solutions (such as conservation, restoration and improved management of forests, wetlands and grasslands) represent more than one-third of the climate mitigation needed by 2030 to stabilize warming to well below 2 °C15. Yet these approaches receive less than 2% of global funds for climate mitigation16. (Energy systems receive more than half.)

In short, the decision-makers backing the global fund for pandemics must not assume that existing funds are dealing with the threat of spillover — they are not. The loss of primary tropical forest was 12% higher in 2020 than in 2019, despite the economic downturn triggered by COVID-19. This underscores the continuing threat to forests.

Funding must be sustained for decades to ensure that efforts to reduce the risk of spillover are in place long enough to yield results.

WHA pandemic agreement

In 2020, the president of the European Council, Charles Michel, called for a treaty to enable a more coordinated global response to major epidemics and pandemics. Last year, more than 20 world leaders began echoing this call, and the WHA launched the negotiation of an agreement (potentially, a treaty or other international instrument) to “strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response” at the end of 2021.

Such a multilateral agreement could help to ensure more-equitable international action around the transfer of scientific knowledge, medical supplies, vaccines and therapeutics. It could also address some of the constraints currently imposed on the WHO, and define more clearly the conditions under which governments must notify others of a potential disease threat. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the shortcomings of the International Health Regulations on many of these fronts17. (This legal framework defines countries’ rights and obligations in the handling of public-health events and emergencies that could cross borders.)

We urge negotiators to ensure that the four actions to prevent spillover outlined here are prioritized in the WHA pandemic agreement. For instance, it could require countries to create national action plans for pandemics that include reducing deforestation and closing or strictly regulating live wildlife markets. A reporting mechanism should also be developed to evaluate progress in implementing the agreement. This could build on experience from existing schemes, such as the WHO Joint External Evaluation process (used to assess countries’ capacities to handle public-health risks) and the verification regime of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Commitments to expand pathogen surveillance at interfaces between humans, domesticated animals and wildlife — from US mink farms and Asian wet markets to areas of high deforestation in South America — should also be wrapped into the WHA agreement. Surveillance will not prevent spillover, but it could enable earlier detection and better control of zoonotic outbreaks, and provide a better understanding of the conditions that cause them. Disease surveillance would improve simply through investing in clinical care for both people and animals in emerging infectious-disease hotspots.

Convention on Biological Diversity

We are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction, and activities that drive the loss of biodiversity, such as deforestation, also contribute to the emergence of infectious disease. Meanwhile, epidemics and pandemics resulting from the exploitation of nature can lead to further conservation setbacks — because of economic damage from lost tourism and staff shortages affecting management of protected areas, among other factors18. Also, pathogens that infect people can be transmitted to other animals and decimate those populations. For instance, an Ebola outbreak in the Republic of Congo in 2002–03 is thought to have killed 5,000 gorillas19.

Yet the global biodiversity framework currently being negotiated by the Convention on Biological Diversity fails to explicitly address the negative feedback cycle between environmental degradation, wildlife exploitation and the emergence of pathogens. The first draft made no mention of pandemics. Text about spillover prevention was proposed in March, but it has yet to be agreed on.

Again, this omission stems largely from the siloing of disciplines and expertise. Just as the specialists relied on for the WHA pandemic agreement tend to be those in the health sector, those informing the Convention on Biological Diversity tend to be specialists in environmental science and conservation.

The global biodiversity framework, scheduled to be agreed at the Conference of the Parties later this year, must strongly reflect the environment–health connection. This means explicitly including spillover prevention in any text relating to the exploitation of wildlife and nature’s contributions to people. Failing to connect these dots weakens the ability of the convention to achieve its own objectives around conservation and the sustainable use of resources.

Preventive health care

A reactive response to catastrophe need not be the norm. In many countries, preventive health care for chronic diseases is widely embraced because of its obvious health and economic benefits. For instance, dozens of colorectal cancer deaths are averted for every 1,000 people screened using colonoscopies or other methods20. A preventive approach does not detract from the importance of treating diseases when they occur.

With all the stressors now being placed on the biosphere — and the negative implications this has for human health — leaders urgently need to apply this way of thinking to pandemics.

Climate change will force new animal encounters — and boost viral outbreaks

Climate change will force new animal encounters — and boost viral outbreaks

One Health approaches require community engagement, education, and international collaborations—a lesson from Rwanda

One Health approaches require community engagement, education, and international collaborations—a lesson from Rwanda