Abstract

The serotonin transporter (SERT) gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) has been implicated in moderating the link between life stress and depression. However, respective molecular pathways of gene–environment (GxE) interaction are largely unknown. Sustained alterations in SERT gene expression profiles, possibly mediated by epigenetic modifications, are a frequent correlate of depression and may thus constitute a putative mediator of GxE interaction. Here, we aimed to investigate joint effects of 5-HTTLPR and self-reported environmental adversity throughout the lifespan (prenatal, early and recent stress/trauma) on in vivo SERT mRNA expression in peripheral blood cells. To further evaluate whether environmentally induced changes in SERT expression are mediated by epigenetic modifications, we analyzed 83 CpG sites within a 799-bp promoter-associated CpG island of the SERT gene using the highly sensitive method of bisulfite pyrosequencing. Participants were 133 healthy young adults. Our findings show that both the 5-HTTLPR S allele and maternal prenatal stress/child maltreatment are associated with reduced in vivo SERT mRNA expression in an additive manner. Remarkably, individuals carrying both the genetic and the environmental risk factors exhibited 32.8% (prenatal stress) and 56.3% (child maltreatment) lower SERT mRNA levels compared with those without any risk factor. Our data further indicated that changes in SERT mRNA levels were unlikely to be mediated by DNA methylation profiles within the SERT CpG island. It is thus conceivable that the persistent changes in SERT expression may in turn relate to altered serotonergic functioning and possibly convey differential disease vulnerability associated with 5-HTTLPR and early adversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research has consistently implicated the joint contribution of genetic and environmental risk factors in the pathogenesis of major depression.1 The most prominent example refers to the debate on whether a 43-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in the serotonin transporter gene2 moderates the association of life stress and depression.3, 4, 5 Whereas numerous studies observed increased disease vulnerability in carriers of the 5-HTTLPR short (S) variant upon exposure to environmental adversity,4,6 recent meta-analyses have triggered an active controversy about whether this finding holds up.7,8 Therefore, exploring systemic and molecular mechanisms underlying gene–environment (GxE) interactions seems to be of major importance to further advance this debate.1,9

On a systemic level, experimental studies investigating biological quantitative traits strongly support the hypothesis of elevated stress sensitivity in S allele carriers.4 Among other biological alterations, the S allele has repeatedly been associated with elevated amygdala activity10,11 and increased cortisol secretion in response to a variety of aversive/stressful stimuli.12,13 However, little is known about the molecular pathways mediating disease vulnerability. One hypothesis is that GxE interaction already takes place at the very early level of gene expression, in a way that 5-HTTLPR and life stress jointly convey stable changes in serotonin transporter (SERT) expression. In line with this, altered SERT expression profiles may constitute a putative mediator of GxE interaction as they have been commonly observed in depressed patients14, 15, 16 and stress-sensitive Rhesus macaques.17,18

The functional effects of 5-HTTLPR have been widely documented by in vitro studies, indicating that the S allele is associated with reduced SERT gene (SLC6A4) transcription in lymphoblast cell lines2,19 and decreased serotonin uptake in platelets.20,21 In addition, transcriptional efficiency of the SERT gene was found to be influenced by an A/G single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs25531) located upstream of the 5-HTTLPR promoter variant within the greater repeat structure.19 This has led to the distinction between the variants S, LA and LG, (tri-allelic classification of 5-HTTLPR) with the latter one being functionally similar to the S allele.19 In contrast to in vitro studies, results obtained in vivo appear to be less conclusive regarding allele-specific SERT mRNA expression in peripheral cells22,23 and SERT availability in the human brain.24, 25, 26 Environmentally-induced changes in SERT expression may partly account for the observed inconsistencies27 but have been sparsely addressed in humans. Animal studies in various species provide first evidence that exposure to early adversity correlates with decreased SERT mRNA levels in the brain28,29 (but also see Gardner et al.30) and in peripheral cells.31 These long-term changes in SERT expression patterns may result from stable epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation.32 Recent studies using peripheral blood cells found that increased methylation levels within a 799-bp promoter-associated CpG island in SLC6A4 associate with both lower SERT mRNA levels23,33, 34, 35 and exposure to childhood trauma,23,36, 37, 38, 39 in some studies dependent on 5-HTTLPR genotype.40 Such peripheral measures of gene expression and DNA methylation profiles have been increasingly recognized as informative biomarkers in psychiatric research.41, 42, 43 Most important for the present study, epigenetic and transcriptional changes in response to environmental adversity appear to be system-wide44,45 and can thus potentially be tracked in easily obtainable blood cells.

The present study aimed to investigate joint effects of 5-HTTLPR and environmental adversity across different developmental stages (prenatal, early, recent trauma/stressors) on peripheral SERT mRNA expression and DNA methylation within the promoter-associated SERT CpG island. As a potential molecular pathway of GxE-mediated disease vulnerability, we expected to find lowest SERT mRNA and highest SERT methylation levels in individuals carrying both the genetic (S allele) and environmental (stress/trauma) risk factor. Studies investigating long-term transcriptional signatures of early adversity implicitly assume that gene expression profiles are characterized by a trait-like component with substantial differences between individuals. Prior studies have generally confirmed a considerable intraindividual stability of genome-wide gene expression patterns over hours and months; however, they have also highlighted that stability varies across individual transcripts.46,47 As intra- and interindividual variation in human SERT mRNA expression has, to the best of our knowledge, not explicitly been evaluated yet, we further conducted a small pilot study investigating respective patterns.

Materials and methods

Pilot study

For the assessment of intra- and interindividual variation in SERT mRNA levels, we obtained SERT mRNA expression day profiles in eight healthy individuals (four females, mean age: 25.0±3.3 years) at two test days separated by 1 week. On each day, seven blood samples were drawn from an indwelling cannula (every 2 h from 0800–2000 hours) into PAXgene blood RNA Tubes (PreAnalytiX, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). As we were interested in normal diurnal fluctuations of SERT mRNA expression, no restrictions were imposed on participants regarding food intake, work flow etc.

Main study: sample and procedure

We recruited participants aged 18–30 years via newspaper advertisement and flyers. Only healthy Caucasian participants who were native German speakers were included in the study. After a structured telephone interview that served as a first screening for exclusion criteria (for example, major health issues), 155 individuals were invited for the main screening and testing session. During this session, the Diagnostic Interview for Psychiatric Disorders—short version (Mini-DIPS48), a structured interview assessing point and lifetime prevalence of axis I disorders based on DSM IV criteria, was conducted. Furthermore, participants completed a comprehensive checklist on chronic physical diseases (for example, cancer, diabetes, heart diseases, asthma and epilepsy) and medication intake (for example, psychotropic drugs). Any current or past mental and/or physical disease as well as medication intake and pregnancy were defined as exclusion criteria. Participants who passed this screening procedure (final sample size: N=133, 63 females) were asked to fill in a set of questionnaires on early and recent life stress/trauma. Data on prenatal stress were obtained within a subsample of 85 participants of whom their mothers agreed to fill in a questionnaire on maternal stress/trauma during pregnancy. At the end of the session, blood samples were drawn into EDTA tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) for DNA and PAXgene blood RNA Tubes (PreAnalytiX, Qiagen) for RNA extraction and stored at −20 °C for no more than 6 months. The pilot and the main study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the ethics committee of the Technische Universität Dresden. Participants provided written informed consent and received a monetary reward for participation.

Assessment of prenatal, early and recent life stress/trauma

In order to assess prenatal stress/trauma, mothers of participants completed the NeuroPattern–Pre-/postnatal-Stress-Questionnaire, which retrospectively records pre-, peri- and postnatal adverse events.49,50 The NPQ-PSQ is part of a translational diagnostic tool (NeuroPattern) for stress-related disorders49 and assesses maternal stressful/traumatic events during pregnancy, such as death or life-threatening illness of a close relative, divorce, lack of social support, relationship conflicts, high workload and financial constraints in a yes/no format. Participants of mothers reporting at least one stressful/traumatic life event during pregnancy were assigned to the prenatal stress group. We further applied the short Form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ),51,52 a widely used retrospective measure of child maltreatment with high internal consistency, reliability and criterion validity.51 Participants were classified as traumatized when CTQ scores exceeded a moderate to severe cutoff score51 in at least one of the five CTQ trauma categories (emotional abuse: >13, physical abuse: >10, sexual abuse: >8, emotional neglect: >15 and physical neglect: >10). In addition, recent stress exposure was assessed using the Life Stressor Checklist—Revised (LSC-R53,54). The LSC-R is a 30-item self-report measure with good psychometric properties54 assessing traumatic and stressful life events (for example, physical/sexual assault, death of a relative, serious accidents/diseases, abortion) in a yes/no format. Participants reporting at least one stressful/traumatic life event within the past 5 years were assigned to the recent stress/trauma group.

5-HTTLPR genotyping

DNA was extracted from EDTA whole blood using a standard commercial extraction kit (High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in a MagNA Pure LC System (Roche). Participants were genotyped for 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 according to a previously published protocol.55

Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed by Varionostic GmbH (Ulm, Germany; http://www.varionostic.de) on the LightCycler 480 I (Roche) using the SensiFast Sybr green mix from Bioline (Luckenwald, Germany). A detailed protocol and primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Information 1. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and b-actin were applied as references for expression. After the mean calculation and delta Cq generation (reference mean-target gene value) values were plotted according to the 2−2ΔΔCt method56 to form relative expression level on a linear scale. Values reflect fold changes in gene expression normalized to both endogenous reference genes. All RT-PCR analyses were performed in duplicates.

Bisulfite pyrosequencing

We analyzed quantitative methylation of 83 CpG sites within a 799-bp promoter-associated CpG island in SLC6A4 (GenBank accession number: NG_011747). Methylation analysis by bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA from EDTA whole blood samples and subsequent pyrosequencing was performed by Varionostic GmbH. Sequencing was performed on the Q24/ID System and percent methylation at each CpG site was quantified using the PyroMark Q24 software (Qiagen). A detailed protocol with amplicon and sequencing primers is provided in Supplementary Information 2. The percentages of methylation values, which passed quality control, were >95% for each individual CpG site.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 21.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and R (R Core Team, 2013). Within the pilot study, intraclass-correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the factors ‘time’ and ‘subject’ were calculated to assess intra- and interindividual variation in SERT expression according to the following model: mRNAi=βsubject+βtime+ɛi, with ɛi~N(0,σ2res).57 Large values indicate that a major fraction of variance in SERT expression can be explained by the respective factor. Furthermore, SERT mRNA area under the curve with respect to ground (AUCG) values were calculated as an integrated measure of total SERT mRNA output according to the trapezoidal formula.58 Pearson correlations of SERT mRNA AUCG values for the two test days were further calculated.

In the main study, χ2 tests for dichotomous and analyses of variance for continuous measures were used to examine group differences regarding demographic characteristics. Effects of 5-HTTLPR and stress/trauma-related measures on SERT expression, mean as well as principal component methylation across the CpG island and methylation at individual CpG sites (Bonferroni-corrected), were tested by general linear models. We have further specified a general linear model incorporating a GxE interaction term in addition to main effects of genotype and stress/trauma. This model was compared with a baseline model assuming additive effects only to evaluate whether GxE interaction explains incremental variance. Regarding genotype as between-subject factor, analyses were conducted both according to the bi-allelic (SS versus SL versus LL) and the tri-allelic classification by comparing the load of high (LA) and low (S, LG) expressing alleles (SS,SLG,LGLG versus SLA,LGLA versus LALA). Furthermore, mediation analyses were conducted assessing the relative contribution of SERT methylation as a mediator of the association between environmental adversity and SERT mRNA expression.59 Pearson correlations were calculated to further evaluate associations between stress/trauma scores and the dependent variables. To identify potential confounds, we tested for associations of sex, oral contraceptives use, body mass index, age and smoking status with our dependent variables as these factors have previously been found to influence gene expression and methylation patterns (for example, the well-documented effects of sex hormones on gene expression and DNA methylation60,61). These analyses were conducted by means of independent t-tests for dichotomous and Pearson correlations for continuous variables.

Results

Pilot study: intra- and interindividual variation in SERT mRNA expression

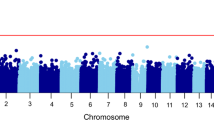

Figure 1 displays SERT expression levels at the 14 different measuring times for each participant and the mean SERT expression patterns across the 2 test days. Our findings revealed that only a small portion of variance in SERT mRNA expression patterns is bound by the factor time (ICCtime=0.05), whereas ICCs indicate a moderate to high between-subject variance (ICCsubject=0.60). We further observed a high intraindividual day-to-day stability of SERT expression patterns as indicated by a strong correlation (r=0.89, P=0.003) between SERT mRNA AUCG across the 2 test days. Our pilot study thus indicates a substantial trait component regarding SERT mRNA expression, given that a higher portion of variance in SERT mRNA expression can be explained by the factor subject (60%) than by other factors (ICCtime+residual variance=40%).

(a) SERT mRNA expression levels (mean±s.e.m.) calculated with the 2−2ΔΔCt method at the 14 different measuring times displayed for each participant separately. Intraclass-correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the factors ‘time’ and ‘subject’ were calculated to assess intra- and interindividual variation in SERT mRNA expression patterns. ICCs can vary between 0 and 1. Large values indicate that a major fraction of variance in SERT expression can be explained by the respective factor. (b) SERT mRNA expression levels (mean±s.e.m.) calculated with the 2−2ΔΔCt method for the 2 test days.

Main study: sample characteristics

Demographic and stress/trauma-related sample characteristics are depicted in Table 1. There was no significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using bi-allelic (x2(1)=0.72, P=0.40) or tri-allelic (x2(3)=2.95, P=0.40) classification of 5-HTTLPR. Genotype groups did not differ regarding the number of reported prenatal, early and recent stressors/trauma (all P-values⩾0.08, Table 1) or with respect to sex, age, body mass index, smoking status and oral contraceptive use (all P-values⩾0.21, Table 1). When participants were assigned to the prenatal, early and recent stress/trauma groups, no significant differences between the respective ‘stress/trauma’ and ‘no stress/trauma’ groups regarding any of the these variables were found (all P-values⩾0.25), except of a higher number of smokers in the ‘early trauma‘ compared with the ‘no early trauma’ group (64.7% versus 30.2%, x2(1)=7.81, P=0.01).

Effects of 5-HTTLPR and stress/trauma-related variables on SERT mRNA expression

Table 2 presents effects of 5-HTTLPR and stress/trauma-related variables across the lifespan on SERT mRNA expression. SERT mRNA levels were found to be unrelated to sex, age, body mass index, smoking status and intake of oral contraceptives (all P-values⩾0.16). As expected, we observed significantly lower SERT mRNA levels in S allele carriers compared with individuals carrying two copies of the L allele (F1,131=5.14; P=0.03; η2=0.04). Similar results were obtained with tri-allelic classification of 5-HTTLPR (F1,131=6.67; P=0.01; η2=0.05). On a genotype level (SS/SL/LL), analyses of variance revealed a borderline significant effect of 5-HTTLPR on SERT mRNA levels (F1,130=2.71; P=0.07; η2=0.04), which reached significance with tri-allelic classification (F1,130=3.31; P=0.04; η2=0.05).

Regarding stress/trauma-related variables, we observed a significant effect of prenatal and early stress/trauma on SERT mRNA levels. Individuals of mothers reporting at least one major stressful/traumatic life event during pregnancy were found to have lower SERT mRNA levels compared with those without maternal prenatal stress (F1,83=5.54; P=0.02; η2=0.06). Furthermore, we observed a negative correlation between the number of prenatal maternal life stressors/trauma and SERT mRNA levels (r=−0.27, P=0.01). A similar reduction in SERT mRNA expression was seen in individuals reporting early traumatization (F1,131=4.15; P=0.04; η2=0.03) when comparing the groups of participants with (mean CTQ score: 48.88±4.38) and without (mean CTQ score: 30.69±8.54) a history of child maltreatment. Within the overall sample, CTQ scores were inversely correlated with SERT mRNA levels (r=−0.18; P=0.04). In contrast, recently experienced stress had no effect on SERT mRNA levels (F1,131=1.17; P=0.19). Our findings further indicated that the S allele and prenatal/early adversity associate with decreased SERT expression in an additive manner as lowest levels were found in individuals carrying both the genetic and the environmental risk factor (prenatal stress: F2,82=3.14; P=0.05; η2=0.07; early trauma: F2,130=4.55; P=0.01; η2=0.07; Figure 2). Specifically, those individuals were found to have 32.8% (prenatal stress) and 56.3% (child maltreatment) lower SERT mRNA levels compared with the group without any of the two risk factors. Including a GxE interaction term in the general linear model did not incrementally increase the portion of variance explained by an additive model (prenatal stress: F1,81=0.86; P=0.36; early trauma: F1,129<0.01, P=0.99).

Effects of stress/trauma-related variables on SERT DNA methylation profiles

We next investigated whether effects of prenatal and early life stress/trauma on SERT mRNA expression levels are mediated by DNA methylation profiles within a 799-bp promoter-associated CpG island in SLC6A4 (Figure 3a). The mean methylation values averaged across the entire CpG island did not differ as a function of sex, age, body mass index and smoking status (all P-values⩾0.14). The use of oral contraceptives was associated with significantly increased mean SERT methylation (F1,61=4.20; P=0.05; η2=0.06) and was thus included as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

(a) The sequence of the SERT promoter-associated CpG island as previously described by Philibert et al.33 (GenBank accession number: NG_011747). CpG sites analyzed by means of bisulfite pyrosequencing are numbered and base pair positions according to the NCBI genome browser are depicted on the left hand side. CpG sites associated with reduced SERT expression are marked by single underlining (uncorrected significance) and double underlining (Bonferroni-corrected significance). CpG sites with increased methylation levels in individuals with prenatal stress exposure are marked by light shading (uncorrected significance) and dark shading (Bonferroni-corrected significance). (b) Boxplots displaying DNA methylation levels across the 83 CpG sites. The box covers the methylation data of each CpG site between 25th bis 75th quantile (median ± one interquartile range), the whiskers represent the range of values that fall within 1.5-fold the interquartile range. The horizontal line reflects the methylation detection limit forbisulfite pyrosequencing.

Our results revealed no significant effect of prenatal (F1,82=0.17; P=0.68), early (F1,130=0.03; P=0.86) or recent (F1,130=0.73; P=0.39) life stress/trauma on the mean SERT methylation levels (Table 2). Furthermore, the mean SERT methylation levels did not differ as a function of 5-HTTLPR (all P⩾0.50, Table 2). Regarding functional relevance of SERT methylation profiles, we observed no significant correlation between the mean methylation levels and SERT mRNA expression (r=0.10, P=0.23). The latter results indicate that effects of prenatal/early adversity on SERT mRNA expression are unlikely to be mediated by overall SERT methylation. For the purpose of completeness, we have additionally calculated mediation analyses, which overall confirmed this presumption (indirect effects: prenatal stress: ß=−0.00003 [CI: −0.00340, 0.00277], early trauma: ß=−0.00014 [CI: −0.00468, 0.00319]).

As absolute levels and interindividual variation in methylation substantially vary across the SERT CpG island (Figure 3b), we further conducted exploratory analyses on the level of individual CpG sites. First, we screened the entire CpG island for sites related to decreased SERT mRNA levels. Methylation levels at 10 out of the 83 CpG sites investigated were associated with lower SERT mRNA expression (all P-values <0.05 uncorrected, Figure 3a); however, only for CpG9 this association remained significant after correcting for multiple testing (r=−0.34, P<0.001). We further observed a considerable overlap of site-specific methylation associated with SERT mRNA expression and prenatal stress/trauma. Individuals exposed to maternal prenatal stress were found to have higher methylation levels at CpG2, CpG9, CpG29 and CpG30 (all P-values <0.05) compared with those without. The latter effect remained significant for CpG30 (F1,83=11.81, P=0.001, η2=0.16) and by trend also for CpG9 (F1,83=8.24, P=0.005, η2=0.09) after Bonferroni-adjustment (Figure 3a). We further observed no associations between early and recent life stress/trauma or 5-HTTLPR and site-specific SERT methylation levels (all P-values⩾0.39).

For completeness, we have further investigated associations of prenatal, early and recent life stress/trauma with SERT methylation levels within the CpG island by means of a partial principal component analysis, which overall revealed no significant results (Supplementary Information 3).

Discussion

In the light of overall conflicting findings on whether the 5-HTTLPR S allele conveys disease vulnerability upon environmental adversity,7,8 this study aimed to explore molecular modifications, which possibly mediate GxE interaction. Here, we report that both the S allele and prenatal/early adversity associate with decreased peripheral SERT mRNA levels in an additive manner and, remarkably, account for a comparable amount of variance in SERT expression. These effects appeared to be largely independent of methylation profiles within the SLC6A4 promoter-associated CpG island.

Our finding of lower SERT mRNA levels in S allele carriers closely parallels previous data from in vitro research2,19, 20, 21 but stands at variance with several brain imaging studies reporting mixed results regarding allele-specific SERT availability.24, 25, 26 Besides inconsistencies related to methodological aspects (see Willeit et al.62), SERT mRNA may simply reflect a more proximate measure of transcriptional activity than SERT availability. Indeed, research across different species has shown SERT mRNA to be subjected to complex post-transcriptional regulation, such as translational repression by miRNA.63, 64, 65 In addition, our findings implicate that differential exposure to early adversity may either overshadow or pronounce allele-specific effects on in vivo SERT mRNA expression (Figure 2) and may thus have contributed to previously observed discrepancies.22,23

To date, the link between environmental adversity and persistent changes in SERT mRNA profiles has almost exclusively been addressed in non-human research. Specifically, maternal separation has been associated with lower raphé SERT mRNA levels in rodents28,29 and decreased SERT availability in non-human primates.66 Likewise, Rhesus macaques exposed to maternal aggression were found to have reduced SERT mRNA levels in peripheral blood cells, indicating that stress-induced changes of SERT expression are not limited to the brain.31 Our study complements and extends previous animal research by demonstrating long-term signatures of early adversity using easily accessible markers of human SERT expression. Here, we provide first evidence for reduced SERT mRNA levels in individuals exposed to maternal prenatal stress or child maltreatment. This observation is strengthened by an inverse correlation between SERT mRNA levels and the magnitude of prenatal/early adversity within the overall sample. Strikingly, we observed no such effect for adult stressors/trauma, hinting towards a sensitive period in early development.67

Epigenetic modifications are considered a promising pathway mediating sustained changes of gene expression in response to early adversity.32 Methylation profiles within a 799-bp CpG island in SLC6A4 have recently been associated with SERT transcription and are further responsive to environmental influences.68 Several in vivo and in vitro studies found site-specific SERT methylation to promote gene silencing in transformed lymphoblast cell lines,23,33 peripheral blood mononucleated cells35 and buccal cells,34 in some studies depending on 5-HTTLPR.40 Our results tentatively concur with previous observations by demonstrating negative correlations of SERT methylation and mRNA expression for 10 out of 83 CpG sites investigated. Although this association remained significant only for CpG9 after Bonferroni correction, the finding of 12% of CpG sites being functionally relevant on an uncorrected level is unlikely to result from chance (B(i⩾10|α=0.05, n=83) <1%). Despite its putative role in transcriptional regulation, we found very limited evidence for SERT methylation mediating associations between environmental adversity and SERT mRNA expression. Regarding childhood trauma, our study conflicts with previous reports linking site-specific SERT methylation to a history of sexual abuse,23,36,37 childhood trauma39 and bullying victimization.38 However, it is of note that no specific CpG site has yet been consistently associated with early adversity across previous studies. Variable findings may result from diversity of used cell populations, examined subregions, methylation detection methods (for example, quantitative mass spectroscopy, Sequenom EpiTYPER platform, pyrosequencing), type of trauma and lack of correction for multiple testing.

Regarding prenatal stress, initial evidence has suggested a positive association between maternal depressed mood during the second trimester and the mean methylation within a subregion of the SERT CpG island (10 CpG sites).69 Whereas we observed no effect on the mean SERT methylation, individuals exposed to maternal prenatal stress were characterized by increased methylation levels at four CpG sites (Bonferroni-corrected at CpG30 and CpG9, at trend level). Although it is tempting to suggest CpG9 methylation as a putative mediator of lower SERT mRNA levels in response to prenatal adversity, caution is advised when interpreting this finding. A closer inspection of CpG9 (Figure 3b), but also of some relevant sites identified by previous studies, revealed that absolute methylation appears to be marginal, falling below the detection limit for the majority of individuals, and is thus unlikely to constitute a valid candidate. Against this background, candidate SERT CpG sites should be carefully selected in consideration of previously observed absolute methylation levels in future studies. Elucidating the precise mechanism of CpG site-specific methylation mediating gene silencing, such as altered transcription factor binding, might further advance this selection process. The lack of robust findings does not rule out the possibility that methylation patterns outside of the investigated region or epigenetic modifications other than methylation may have mediated effects of early adversity on SERT expression. Interestingly, genome-wide analyses have suggested the possibility that methylation patterns associated with gene expression are more likely to be located outside CpG islands.70 Supporting this notion, a recent study reports that methylation in the shore of the SERT CpG island upstream from exon 1A predicts SERT expression, thus identifying this region as a potential target for future studies.23

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, our findings rely on retrospective self-report measures of environmental adversity, which could be subject to bias. However, the finding of reduced SERT mRNA expression being a correlate of early adversity appears to be consistent across different sources of self-report. Furthermore, larger studies are needed to evaluate differential effects of specific types of stressors/trauma on SERT expression levels. Second, findings of the present study that were obtained in a homogeneous sample of healthy young Caucasian individuals may not generalize to other ethnic groups. Third, it remains to be elucidated whether findings obtained with peripheral markers of SERT expression and methylation profiles generalize to brain tissue. Despite being tissue-specific, post-mortem studies have revealed substantial correlations across peripheral and neural cells for both gene expression71 and DNA methylation patterns.72 Regarding SERT in particular, a recent brain imaging study73 indicates that peripheral SERT methylation is indeed an informative marker for in vivo serotonin synthesis. Even more importantly, environmentally induced modifications in gene expression and methylation patterns appear to be system-wide44,45 supporting the usefulness of peripheral markers for the present study. Lastly, the choice of analyzing whole blood was motivated by the fact that it is readily available, allows to stabilize RNA at the time of blood draw and, importantly, does not require transformation known to modify methylation profiles.74 Despite these advantages, the heterogeneous mixture of cell types may constitute a potential confound, although expression levels of very few mRNA transcripts were found to depend on cell composition.47

In conclusion, our findings raise the assumption of lower SERT mRNA expression being a correlate of both the 5-HTTLPR S allele and prenatal/early adversity. Strikingly, individuals carrying both the genetic and one of the environmental risk factors were found to have 32.8% (maternal prenatal stress) and 56.3% (child maltreatment) lower SERT mRNA levels compared with those without any risk factor. Sustained alterations in SERT expression profiles may in turn relate to changes in serotonergic functioning and thus constitute a possible molecular pathway mediating disease vulnerability as a function of GxE. In accordance with genome-wide transcriptomics analyses,46,47 preliminary evidence from our pilot study suggests that interindividual variability in SERT expression is substantially higher compared with intraindividual variation, thus highlighting the potential usefulness of this specific transcript as a biomarker. Although not without inconsistencies,75, 76, 77 numerous studies indeed suggest that lower SERT expression in the brain and periphery associates with major depression,14, 15, 16 treatment efficacy14,78,79 and increased stress sensitivity.17,18 Since the mean age of onset for depression80 is slightly higher compared with the mean age of our sample, altered SERT expression levels could be discussed in terms of a premorbid risk factor for the development of stress-related psychopathology later in life. Future evaluation of such putative biomarkers of disease vulnerability in longitudinal designs may not only shed light on the pathogenesis of stress-related psychopathology but may also bear important implications for predictive testing. In line with this assumption, peripheral blood gene expression profiles measured in the third trimester of pregnancy have been found to reliably predict subsequent postpartum depression within a high-risk cohort.43 Moreover, peripheral markers of gene expression may help to identify unique disease-related transcriptional signatures associated with specific genetic and environmental risk factors as shown for post-traumatic stress disorder.42

Accession codes

References

Klengel T, Binder EB . Gene-environment interactions in major depressive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2013; 58: 76–83.

Lesch K-PP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996; 274: 1527–1531.

Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE . Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003; 301: 386–389.

Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE . Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167: 509–527.

Wankerl M, Wüst S, Otte C . Current developments and controversies: does the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) modulate the association between stress and depression? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010; 23: 582–587.

Uher R, McGuffin P . The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update. Mol Psychiatry 2010; 15: 18–22.

Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang K-Y, Eaves L, Hoh J et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 301: 2462–2471.

Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S . The Serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 444–454.

Northoff G . Gene, brains, and environment—genetic neuroimaging of depression. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2013; 23: 133–142.

Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science 2002; 297: 400–403.

Murphy SE, Norbury R, Godlewska BR, Cowen PJ, Mannie ZM, Harmer CJ et al. The effect of the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) on amygdala function: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2013; 18: 512–520.

Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Minor KL, Hallmayer J . HPA axis reactivity: a mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63: 847–851.

Miller R, Wankerl M, Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, Alexander N . The serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) and cortisol stress reactivity: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2013; 9: 1018–1024.

Iga J-I, Ueno S-I, Yamauchi K, Motoki I, Tayoshi S, Ohta K et al. Serotonin transporter mRNA expression in peripheral leukocytes of patients with major depression before and after treatment with paroxetine. Neurosci Lett 2005; 389: 12–16.

Mehta D, Menke A, Binder EB . Gene expression studies in major depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010; 12: 135–144.

Lima L, Mata S, Urbina M . Allelic isoforms and decrease in serotonin transporter mRNA in lymphocytes of patients with major depression. Neuroimmunomodulation 2005; 12: 299–306.

Bethea CL, Streicher JM, Mirkes SJ, Sanchez RL, Reddy AP, Cameron JL . Serotonin-related gene expression in female monkeys with individual sensitivity to stress. Neuroscience 2005; 132: 151–166.

Bethea CL, Phu K, Reddy AP, Cameron JL . The effect of short-term stress on serotonin gene expression in high and low resilient macaques. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2013; 44: 143–153.

Hu X-Z, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 78: 815–826.

Greenberg BD, Tolliver TJ, Huang S-J, Li Q, Bengel D, Murphy DL . Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region affects serotonin uptake in human blood platelets. Am J Med Genet 1999; 88: 83–87.

Stoltenberg SF, Twitchell GR, Hanna GL, Cook EH, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA et al. Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, peripheral indexes of serotonin function, and personality measures in families with alcoholism. Am J Med Genet 2002; 114: 230–234.

Singh YS, Altieri SC, Gilman TL, Michael HM, Tomlinson ID, Rosenthal SJ et al. Differential serotonin transport is linked to the rh5-HTTLPR in peripheral blood cells. Transl Psychiatry 2012; 2: e77.

Vijayendran M, Beach SRH, Plume JM, Brody GH, Philibert RA . Effects of genotype and child abuse on DNA methylation and gene expression at the serotonin transporter. Front Psychiatry 2012; 3: 55.

van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Staley JK, Jacobsen LK, Seibyl JP, Laruelle M et al. Central serotonin transporter availability measured with [123I]beta-CIT SPECT in relation to serotonin transporter genotype. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 525–531.

Praschak-Rieder N, Kennedy J, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Boovariwala A, Willeit M et al. Novel 5-HTTLPR allele associates with higher serotonin transporter binding in putamen: A [11C] DASB positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62: 327–331.

Murthy N, Selvaraj S, Cowen P, Bhagwagar Z . Serotonin transporter polymorphisms (SLC6A4 insertion/deletion and rs25531) do not affect the availability of 5-HTT to [ 11 C] DASB binding in the living brain. NeuroImage 2010; 52: 50–54.

Kalbitzer J, Erritzoe D, Holst KK, Nielsen F, Marner L, Lehel S et al. Seasonal changes in brain serotonin transporter binding in short serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region-allele carriers but not in long-allele homozygotes. BPS 2010; 67: 1033–1039.

Own LS, Iqbal R, Patel PD . Maternal separation alters serotonergic and HPA axis gene expression independent of separation duration in c57bl/6 mice. Brain Res 2013; 1515: 29–38.

Lee J-H, Kim HJ, Kim JG, Ryu V, Kim B-T, Kang D-W et al. Depressive behaviors and decreased expression of serotonin reuptake transporter in rats that experienced neonatal maternal separation. Neurosci Res 2007; 58: 32–39.

Gardner KL, Hale MW, Lightman SL, Plotsky PM, Lowry CA . Adverse early life experience and social stress during adulthood interact to increase serotonin transporter mRNA expression. Brain Res 2009; 1305: 47–63.

Kinnally EL, Tarara ER, Mason WA, Mendoza SP, Abel K, Lyons LA et al. Serotonin transporter expression is predicted by early life stress and is associated with disinhibited behavior in infant rhesus macaques. Genes Brain Behav 2010; 9: 45–52.

Meaney MJ . Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene x environment interactions. Child Dev 2010; 81: 41–79.

Philibert RA, Sandhu H, Hollenbeck N, Gunter T, Adams W, Madan A . The relationship of 5HTT( SLC6A4) methylation and genotype on mRNA expression and liability to major depression and alcohol dependence in subjects from the Iowa Adoption Studies. Am J Med Genet 2008; 147B: 543–549.

Olsson CA, Foley DL, Parkinson-Bates M, Byrnes G, McKenzie M, Patton GC et al. Prospects for epigenetic research within cohort studies of psychological disorder: a pilot investigation of a peripheral cell marker of epigenetic risk for depression. Biol Psychol 2010; 83: 159–165.

Kinnally EL, Capitanio JP, Leibel R, Deng L, LeDuc C, Haghighi F et al. Epigenetic regulation of serotonin transporter expression and behavior in infant Rhesus macaques. Genes Brain Behav 2010; 9: 575–582.

Beach SRH, Brody GH, Todorov AA, Gunter TD, Philibert RA . Methylation at SLC6A4 is linked to family history of child abuse: an examination of the Iowa Adoptee sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010; 153B: 710–713.

Beach SRH, Brody GH, Todorov AA, Gunter TD, Philibert RA . Methylation at 5HTT mediates the impact of child sex abuse on women’s antisocial behavior: an examination of the Iowa adoptee sample. Psychosom Med 2011; 73: 83–87.

Ouellet-Morin I, Wong CCY, Danese A, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Mill J et al. Increased serotonin transporter gene (SERT) DNA methylation is associated with bullying victimization and blunted cortisol response to stress in childhood: a longitudinal study of discordant monozygotic twins. Psychol Med 2013; 9: 1813–1823.

Kang H-J, Kim J-M, Stewart R, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, Kim S-W et al. Association of SLC6A4 methylation with early adversity, characteristics and outcomes in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2013; 44: 23–28.

Philibert R, Madan A, Andersen A . Serotonin transporter mRNA levels are associated with the methylation of an upstream CpG island—Philibert—2006—American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics—Wiley Online Library. Am J Med Genet Part B 2007; 144B: 101–105.

Klengel T, Pape J, Binder EB, Mehta D . The role of DNA methylation in stress-related psychiatric disorders. Neuropharmacology 2014; 80C: 115–132.

Mehta D, Klengel T, Conneely KN, Smith AK, Altmann A, Pace TW et al. Childhood maltreatment is associated with distinct genomic and epigenetic profiles in posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 8302–8307.

Mehta D, Newport DJ, Frishman G, Kraus L, Rex-Haffner M, Ritchie JC et al. Early predictive biomarkers for postpartum depression point to a role for estrogen receptor signaling. Psychol Med 2014; 5: 1–14.

Lee RS, Tamashiro KLK, Yang X, Purcell RH, Harvey A, Willour VL et al. Chronic corticosterone exposure increases expression and decreases deoxyribonucleic acid methylation of Fkbp5 in mice. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 4332–4343.

Szyf M, Bick J . DNA methylation: a mechanism for embedding early life experiences in the genome. Child Dev 2013; 84: 49–57.

De Boever P, Wens B, Forcheh AC, Reynders H, Nelen V, Kleinjans J et al. Characterization of the peripheral blood transcriptome in a repeated measures design using a panel of healthy individuals. Genomics 2014; 103: 31–39.

Eady JJ, Wortley GM, Wormstone YM, Hughes JC, Astley SB, Foxall RJ et al. Variation in gene expression profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy volunteers. Physiol Genomics 2005; 22: 402–411.

Margraf J . Entstehung und Handhabung des Mini-DIPS. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 1994.

Hellhammer D, Hero T, Gerhards F, Hellhammer J . Neuropattern: a new translational tool to detect and treat stress pathology I. Strategical consideration. Stress 2012; 15: 479–487.

Hero T, Gerhards F, Thiart H, Hellhammer DH, Linden M . Neuropattern: a new translational tool to detect and treat stress pathology. II. The Teltow study. Stress 2012; 15: 488–494.

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 2003; 27: 169–190.

Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Mensebach C, Grabe HJ, Hill A, Gast U et al. [The German version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): preliminary psychometric properties]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2010; 60: 442–450.

Wolfe J, Kimerling R . Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In Wilson J, Keane TM (eds). Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD, Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1997, pp 192–238.

Ungerer O, Deter H-C, Fikentscher E, Konzag TA . Verbesserte diagnostik von traumafolgestörungen durch den einsatz der life-stressor checklist. Psychother Psych Med 2010; 60: 434–441.

Alexander N, Kuepper Y, Schmitz A, Osinsky R, Kozyra E, Hennig J . Gene–environment interactions predict cortisol responses after acute stress: Implications for the etiology of depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009; 34: 1294–1303.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD . Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001; 25: 402–408.

Pinheiro J, Bates DM . Mixed Effects Models in S and S-Plus. Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000.

Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH . Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28: 916–931.

Preacher KJ, Kelley K . Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods 2011; 16: 93–115.

Ulrich CM, Toriola AT, Koepl LM, Sandifer T, Poole EM, Duggan C et al. Metabolic, hormonal and immunological associations with global DNA methylation among postmenopausal women. Epigenetics 2012; 7: 1020–1028.

McQueen JK, Wilson H, Sumner BE, Fink G . Serotonin transporter (SERT) mRNA and binding site densities in male rat brain affected by sex steroids. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1999; 63: 241–247.

Willeit M, Praschak-Rieder N . Imaging the effects of genetic polymorphisms on radioligand binding in the living human brain: a review on genetic neuroreceptor imaging of monoaminergic systems in psychiatry. NeuroImage 2010; 53: 878–892.

Baudry A, Mouillet-Richard S, Schneider B, Launay J-M, Kellermann O . miR-16 targets the serotonin transporter: a new facet for adaptive responses to antidepressants. Science 2010; 329: 1537–1541.

Millan MJ . MicroRNA in the regulation and expression of serotonergic transmission in the brain and other tissues. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2011; 11: 11–22.

Moya PR, Wendland JR, Salemme J, Fried RL, Murphy DL . miR-15a and miR-16 regulate serotonin transporter expression in human placental and rat brain raphe cells. Int J Neuropsychopharm 2013; 16: 621–629.

Ichise M . Effects of early life stress on [11C]DASB positron emission tomography imaging of serotonin transporters in adolescent peer- and mother-reared Rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 4638–4643.

Heim C, Binder EB . Current research trends in early life stress and depression: Review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene–environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol 2012; 233: 102–111.

Booij L, Wang D, Levesque ML, Tremblay RE, Szyf M . Looking beyond the DNA sequence: the relevance of DNA methylation processes for the stress-diathesis model of depression. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2013; 368: 20120251–20120251.

Devlin AM, Brain U, Austin J, Oberlander TF . Prenatal exposure to maternal depressed mood and the MTHFR C677T variant affect SLC6A4 methylation in infants at birth. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e12201.

van Eijk KR, De Jong S, Boks MP, Langeveld T, Colas F, Veldink JH et al. Genetic analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression levels in whole blood of healthy human subjects. BMC Genomics 2012; 13: 1–1.

Sullivan PF, Fan C, Perou CM . Evaluating the comparability of gene expression in blood and brain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2006; 141B: 261–268.

Byun H, Siegmund K, Pan F . Epigenetic profiling of somatic tissues from human autopsy specimens identifies tissue-and individual-specific DNA methylation patterns. Hum Mol Genet 2009; 18: 4808–4817.

Wang D, Szyf M, Benkelfat C, Provençal N, Turecki G, Caramaschi D et al. Peripheral SLC6A4 DNA methylation is associated with in vivo measures of human brain serotonin synthesis and childhood physical aggression. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e39501.

Åberg K, van den Oord EJCG . Epstein–Barr virus transformed DNA as a source of false positive findings in methylation studies of psychiatric conditions. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 70: e25–e26.

Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Hu X, Goldman D, Huang Y-Y et al. Effect of a triallelic functional polymorphism of the serotonin-transporter-linked promoter region on expression of serotonin transporter in the human brain. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 48–51.

Tsao C-W, Lin Y-S, Chen C-C, Bai C-H, Wu S-R . Cytokines and serotonin transporter in patients with major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006; 30: 899–905.

Cannon DM, Ichise M, Rollis D, Klaver JM, Gandhi SK, Charney DS et al. Elevated serotonin transporter binding in major depressive disorder assessed using positron emission tomography and [11C]DASB; comparison with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62: 870–877.

Miller JM, Oquendo MA, Ogden RT, Mann JJ, Parsey RV . Serotonin transporter binding as a possible predictor of one-year remission in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2008; 42: 1137–1144.

Belzeaux R, Formisano-Tréziny C, Loundou A, Boyer L, Gabert J, Samuelian J-C et al. Clinical variations modulate patterns of gene expression and define blood biomarkers in major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2010; 44: 1205–1213.

Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V . Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med 2010; 40: 225–237.

Acknowledgements

The current study was funded by a grant from the German Research Foundation to Nina Alexander (AL 1484/2-1) and was further supported by a grant from the Technische Universität Dresden to Matthis Wankerl for conducting the pilot study. We thank Sandra Zänkert, Maximilian Trompetter and Karolin Gruner for assisting participant recruitment and blood draw. We are further grateful for the valuable laboratory work of Cornelia Meineke.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wankerl, M., Miller, R., Kirschbaum, C. et al. Effects of genetic and early environmental risk factors for depression on serotonin transporter expression and methylation profiles. Transl Psychiatry 4, e402 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.37

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.37

This article is cited by

-

Prenatal exposure to environmental air pollution and psychosocial stress jointly contribute to the epigenetic regulation of the serotonin transporter gene in newborns

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

No long-term effects of antenatal synthetic glucocorticoid exposure on epigenetic regulation of stress-related genes

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

A systematic review of childhood maltreatment and DNA methylation: candidate gene and epigenome-wide approaches

Translational Psychiatry (2021)

-

Association of serotonin system-related genes with homicidal behavior and criminal aggression in a prison population of Pakistani Origin

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

The impact of COMT, BDNF and 5-HTT brain-genes on the development of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review

Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity (2021)