Abstract

Sham electroacupuncture (EA) control is commonly used to evaluate the specific effects of EA in randomized-controlled trials (RCTs). However, establishing an inert and concealable sham EA control remains methodologically challenging. Here, we aimed to systematically investigate the sham EA methods. Eight electronic databases were searched from their inception to April 2015. Ten out of the 17 sham EA methods were identified from 94 RCTs involving 6134 participants according to three aspects: needle location, depth of needle insertion and electrical stimulation. The top three most frequently used types were sham EA type A, type L and type O ordinally. Only 24 out of the 94 trials reported credibility tests in six types of sham EA methods and the results were mainly as follows: sham EA type A (10/24), type B (5/24) and type Q (5/24). Compared with sham EA controls, EA therapy in 56.2% trials reported the specific effects, of which the highest positive rate was observed in type N (3/4), type F (5/7), type D (4/6) and type M (2/3). In conclusion, several sham EA types were identified as a promising candidate for further application in RCTs. Nonetheless, more evidence for inert and concealable sham EA control methods is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been the cornerstone of medical clinical research since the first RCT paper entitled “Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a Medical Research Council investigation” was published in 19481. By the late 20th century, RCT was recognized as the gold standard for a clinical trial2. To improve the quality of clinical research, the methodology has been refined to avoid any bias over the past several decades. The most important design techniques for avoiding bias in clinical trials are randomization and blinding. Blinding is intended to limit the occurrence of conscious and unconscious bias in clinical trials (performance bias) conduction and interpretation of outcomes (ascertainment bias)3. Blinding is crucial for treatment evaluation because lack of blinding can bias the reliable assessment of treatment effects. For RCTs, placebo is a standard control method to blind the participants and health care providers. The purpose of placebo group is to account for the placebo effect, i.e., effects from treatment that do not depend on the treatment itself. However, blinding is difficult to ensure in non-pharmacological treatment trials because fabrication of placebo such as placebo/sham acupuncture controls requires the placebo to be both inert and indistinguishable, which is relatively difficult4.

RCTs for acupuncture appeared in 1970s5. Since then, a number of RCTs on acupuncture have been published6. The “sham” acupuncture is identified as the procedure controlling for the acupuncture treatment components with the aim to blind the participants and control for non-specific placebo effects7. Since participants are to a large extent ignorant of the components of acupuncture such as needle location, depth of needle insertion, needle stimulation and patient/practitioner interactions, sham acupuncture can be considered to be therapeutically inactive. However, it is difficult to design a standard method for sham acupuncture avoiding all therapeutically active components. Thus, the methodological difficulties in designing appropriate sham acupuncture controls for RCTs remained challenging8,9,10.

Electroacupuncture (EA) is an extension technique based on traditional acupuncture combined with modern electrotherapy11,12. Owing to its accurate, reproducible and standardized intensity and duration of stimulation with simple, verifiable electrical parameters, EA has been widely used in clinical studies and basic research into underlying mechanisms of acupuncture treatment13,14. Currently, EA is being used extensively in China and elsewhere around the world. However, no systematic analyses have yet been published to describe the sham EA procedures. Thus, the objective of this study is to investigate the sham EA methods utilized in EA RCTs.

Methods

Search strategy

Eight electronic databases, including Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, PubMed, EMBASE, AMED, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Journals Database, Wanfang database, and Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) were searched from their inceptions to April 2015. The search terms were confined to “Electroacupuncture” AND “sham acupuncture OR placebo acupuncture” AND “randomized controlled trial (RCT)”. All searches were limited to studies on human.

Eligibility Criteria

RCTs concerning the effects of EA on any kind of diseases with at least one control group receiving sham EA were included, regardless of publication status and languages. Quasi-RCTs and non-RCTs were excluded.

The studies were eligible if EA therapy alone or adjunct therapy were given in treatment group and secondly, if sham EA or any type of faked manipulation mimicking real EA in aspects of acupoint, penetration and electro-stimulation were given in control group. There were no restrictions on needle parameters or intensity, frequency and mode of stimulation. Studies that compared EA with transcutaneous nerve electrical stimulation (TNES), another acupuncture plus sham EA or placebo medications were excluded. If three or more groups were designed in one study, only real EA versus sham EA groups were included.

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors (ZXC, YL) reviewed the titles and abstracts of the potential references independently. All the potentially relevant studies were marked and their full articles were retrieved. Further examinations were carried out to make a final selection decision. The same two authors performed the data extraction independently for the predefined items: author, year, country, EA indications, sample size, the characteristics of interventions, outcome measures, results and dropouts. The disagreements were resolved through consulting a third part (GQZ).

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (ZXC and YL) performed the methodological quality assessment of each included trial independently based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias14. The criteria consisted of the following: adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of personnel, blinding of outcome assessor, free of incomplete outcome data, free of selective reporting and free of other bias.

Description of sham EA methods

The sham EA methods used in each control group were examined and the details were extracted according to three respects: needle location, depth of needle insertion and electrical stimulation. Partially based on the previous sham acupuncture type I~V classification published by Dincer et al.8 we summarized seventeen kinds of sham EA methods: (1) Sham EA on therapeutic acupoints plus no skin penetration plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type A); (2) Sham EA on therapeutic acupoints plus no skin penetration plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type B); (3) Sham EA on therapeutic acupoints plus the same depth plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type C); (4) Sham EA on therapeutic acupoints plus superficial insertion plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type D); (5) Sham EA on therapeutic acupoints plus superficial insertion plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type E); (6) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus the same depth plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type F); (7) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus the same depth plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type G); (8) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus superficial insertion plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type H); (9) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus superficial insertion plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type I); (10) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus no skin penetration plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type J); (11) Sham EA on nonspecific acupuncture points plus no skin penetration plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type K); (12) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus the same depth plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type L); (13) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus the same depth plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type M); (14) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus superficial insertion plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type N); (15) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus superficial insertion plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type O); (16) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus no skin penetration plus electrical stimulation (Sham EA type P); (17) Sham EA on non-acupuncture points plus no skin penetration plus no electrical stimulation (Sham EA type Q).

Assessment of the effectiveness

Considering wildly varying outcome measures across different disease conditions, treatment efficacy was evaluated for each study according to the modified method based on a previous publication10. The results of each trial were presented by using the following primary outcome measures: “T > C” meaning that real EA treatment group was significantly superior to sham EA control group; “ND” meaning no difference between EA and sham EA groups; “T < C” meaning that real EA group was significantly inferior to sham EA group. If the efficacy of a trial was reported as “T > C” or “T < C” without between-groups comparison having been conducted, we collected the original data by reviewing the articles or contacting the corresponding author. If the original data were available, an effect-size analysis was conducted to reconfirm the between-groups difference. If the original data were not available, the efficacy results were presented as “T > C?” or “T < C?”.

The credibility of blinding

The credibility test was formally performed in validation studies to assess the blinding effect of sham acupuncture based on credibility questionnaire and statistical analysis15,16,17. The information on the credibility test was extracted to explore the relationship between the credibility of blinding and the type of sham EA method.

Results

Study selection

A total of 679 potentially relevant articles were identified. By reviewing titles and abstracts, 374 papers were excluded for at least one of following reasons: (1) not clinical trials; (2) case report, comment, review, letter, news or editorial; (3) not in contrast with sham EA; (4) lack of EA intervention. After examining the full content of the remaining 305 articles, we removed 211 records, of which 127 articles were due to lack of sham EA controls, including electro-acupuncture (14 studies), manual acupuncture (13 studies), TNES (7 studies), other treatment (69 studies) or no treatment (24 studies); 49 articles removed for lack of real EA groups, with their target intervention designed as manual acupuncture (10 studies), TNES (38 studies) or periosteal stimulation therapy (PST) (1 study); 10 articles were not RCTs; 13 articles were double publications; 12 articles were cross-over design. Ultimately, 94 studies18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111 involving 6134 participants were selected (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

The 94 included articles were published from 1992 to 2015. Among them, 5 studies29,54,90,95,107 were published between 1992 and 1999; 33 studies22,24,25,27,30,31,38,45,47,52,53,56,57,58,67,68,71,72,73,74,77,78,81,83,84,92,93,97,104,105,106,110,111 were published between 2000 and 2010; the remaining 56 studies18,19,20,21,23,26,28,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,48,49,50,51,55,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,69,70,75,76,79,80,82,85,86,87,88,89,91,94,96,98,99,100,101,102,103,108,109 were reported from 2010 to 2015 (Fig. 2). Indications for EA included pain (32 studies)18,19,21,24,26,27,31,33,36,37,40,42,45,47,51,52,56,60,66,67,72,76,82,84,88,90,92,96,97,103,110,111, anesthesia (8 studies)46,50,73,74,86,89,94,102, stroke (7 studies)25,28,29,34,62,105,106, depression (6 studies)23,53,59,65,68,80, obesity (4 studies)32,49,54,70, primary dysmenorrheal/menstrual pain (4 studies)61,98,99,101, substance abuse (heroin or smoking) (3 studies)64,95,107, osteoarthritis (2 studies)22,104, migraine (2 studies)39,78, nausea and vomiting (2 studies)38,57, postoperative ileus (2 studies)35,91, insomnia (2 studies)63,81, benign prostate hyperplasia (2 studies)79,87, diabetic mellitus related diseases (2 studies)83,109, carpal tunnel syndrome (1 study)100, rheumatoid arthritis (1 study)93, whiplash-associated disorders (1 study)69, constipation (1 study)48, multiple sclerosis (1 study)41, tinnitus (1 study)20, auditory hallucination (1 study)30, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (1 study)44, polycystic ovary syndrome (1 study)55, hot flushes (1 study)58, postpartum insufficient lactation (1 study)71, cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury (1study)75, stress-related symptoms (1 study)108. The rest three studies43,77,85 reported the effects of EA on healthy subjects.

EA treatment alone was adopted in 55 trials19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43,53,55,58,60,61,66,68,69,71,72,75,77,78,79,80,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,95,98,99,100,101,103,104,107,108,110,111, while the interventions of the remaining 39 trials were a combination of EA and western conventional medicine (WCM). Four trials24,47,54,100 were designed as two groups of EA, and seven trials38,43,61,63,98,99,101 were conducted with two groups of sham EA. Compared with sham EA group, real EA group in 83 studies selected the same number of acupoints; nine studies25,46,66,89,90,105,106,108,111 used more number of acupoints; one study20 used less number of acupoints; one study52 did not report the number of acupoints. Eight studies26,49,54,76,95,96,97,110 identified acupoints by using a point detector. The “deqi” sensation was required in 65 real EA groups18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,29,30,31,33,34,35,36,39,40,41,43,44,47,48,50,51,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,69,71,75,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,85,86,87,90,91,93,98,99,100,101,102,104,105,106,109,111 and 3 sham EA groups selected nonspecific acupoints61,78,101. Eight studies utilized pricking sensation to mimic needle sensation and blind participants in control group20,21,23,52,60,63,67,81. Forty-two studies19,20,21,22,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,42,43,44,46,47,50,51,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,70,71,77,78,79,83,85,89,92,100,104,105,106 applied EA at high intensity with maximum tolerance, and seventeen studies24,29,54,56,59,80,82,86,87,90,95,98,99,102,107,108,111 applied EA with low intensity below pain threshold or at a comfortable level with presence or absence of muscle contractions. The other trials were lacking in details on the intensity of stimulation. The duration of each session ranged from 5 minutes100 to 72 hours96; the total number of treatment sessions varied from 133,37,38,39,46,47,50,51,52,72,73,77,82,84,86,88,89,94,95,96,97,100,101,102,109 to 7244; the total duration of treatment ranged from 5 minutes100 to 6 months111. Ten studies27,46,72,76,77,79,89,90,97,102 did not report the duration of each session. In one study76, the total number of treatment session was not mentioned. Eight studies27,46,72,76,77,89,97,102 did not provide any information on the total duration of treatment. The characteristics of the studies were listed in Table 1.

Characteristics of sham EA

Ten different types of sham EA methods used in the trials were identified as follows: (1) sham EA type A were used in twenty-six control groups18,19,20,21,22,31,33,37,40,60,66,67,73,74,76,81,94,96,97,102,103,104,106,108,109,110; (2) sham EA type B were used in seven control groups23,24,59,65,84,88,105; (3) sham EA type C were used in seven control groups28,44,47,49,51,75,82; (4) sham EA type D were used in six control groups29,43,62,64,72,93; (5) sham EA type F were used in seven control groups38,61,71,78,98,99,101; (6) sham EA type L were used in seventeen control groups26,27,39,43,46,48,50,53,54,61,77,79,85,89,98,99,101; (7) sham EA type M were used in three control groups42,68,69; (8) sham EA type N were used in four control groups63,83,90,95; (9) sham EA type O were used in fourteen control groups30,32,35,41,45,56,57,58,70,80,86,87,91,92; and (10) sham EA type Q were used in ten control groups25,34,36,38,52,55,63,100,107,111.

For the needle location, 48 sham EA groups25,26,27,30,32,34,35,36,38,39,41,42,43,45,46,48,50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,61,63,68,69,70,77,79,80,83,85,86,87,89,90,91,92,95,98,99,100,101,107,111 chose non-acupoints that were either located away from the therapeutic acupoints with a distance ranging from 1 cm to 40 cm or devised in advance to avoid any known meridian or extra-point. Seven sham EA groups38,61,71,78,98,99,101 received nonspecific acupuncture points which were thought to be ineffective for treating the diseases. For the depth of needle insertion, 34 sham EA groups26,27,28,38,39,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,61,68,69,71,75,77,78,79,82,85,89,98,99,101 conducted the needle insertion to the same depth as corresponding real EA groups. Twenty-four sham EA groups29,30,32,35,41,43,45,56,57,58,62,63,64,70,72,80,83,86,87,90,91,92,93,95 performed either superficial or subcutaneous needle insertion with depth varying from 0.5 mm to 2 cm, whereas one study93 retracted the needle after superficial penetration. The remaining 43 sham EA groups had sham EA without skin penetration. Forty-one out of 43 trials did not apply any needle insertion by using Streitberger needles21,23,25,31,36,55,59,63,65,66,81, contractible placebo needles with dull tips and tubes24,37,52, placebo needles with blunted tips19,20,40,60,67,100, verum needles fixed by tapes or rings without piercing18,22,34, leading wires alone without needles33,38,76,97 and mock laser pen103 or electrodes73,74,94,96,102,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111. Two sham EA groups84,88 did not describe any details on the sham needles. For electrical stimulation, 35 sham EA groups23,24,26,27,38,39,43,46,48,50,53,54,59,61,63,65,71,77,78,79,83,84,85,88,89,90,95,98,99,101,105 used electrical stimulation, whereas two sham EA groups stimulated with current just at the beginning of sham procedure. The other sham EA groups18,19,20,21,22,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,49,51,52,55,56,57,58,60,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,80,81,82,86,87,91,92,93,94,96,97,100,102,103,104,106,107,108,109,110,111 did not receive any electrical stimulation through inactivated EA device or disconnected cables. The details of sham EA were described in Table S1.

Risk of bias assessment

The number of items complied with the criteria varied from 3/8 to 7/8 with the average of 5.2. All 94 studies declared randomization and 63 studies reported the details. Among them, 49 studies18,19,22,23,24,25,27,29,35,36,37,38,42,43,44,45,47,49,51,55,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,70,71,72,81,88,90,91,92,93,96,97,98,99,102,106,107,108,109,110,111 described a computer-generated randomization; 11 studies32,40,41,50,52,57,69,73,74,85,86 were based on random number Table; 3 studies83,87,101 used the lot. Adequate allocation concealment was found in 43 studies18,19,20,23,25,29,30,35,36,37,43,44,45,55,57,58,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,69,71,72,76,79,81,84,86,88,90,91,93,98,99,105,106,107,109,110,111 with sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes or independent administrator. The remaining 51 studies did not provide the details on allocation concealment. Blinding of participant was described in all 94 studies. Among these, 23 studies22,23,25,34,36,45,52,57,59,60,63,65,72,81,88,97,102,103,105,106,107,108,110 proved their success of blinding by credibility test, while one study66 failed in blinding of participant after testing by statistical analysis. No study mentioned blinding of acupuncturists. Ninety-two out of the 94 studies reported blinding of assessor, whereas one study54 did not contain any information on assessor blinding and another study66 was sorted as “no” due to its unsuccessful assessor blinding. Eighteen studies25,30,45,60,65,69,79,80,91,92,93,97,98,99,103,105,106,107 conducted intention-to-treat analysis. Seventy-five studies18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,46,47,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,94,95,96,97,100,101,102,103,104,105,108,109,110,111 were free of incomplete outcome data; eleven studies23,42,45,48,69,80,93,98,99,106,107 assessed as “no” due to high dropout rate or statistically significant differences between groups in withdrawals from the treatment. The rest were unclear due to lack of information on this aspect. Sixteen studies36,39,41,42,44,59,63,64,75,79,80,86,91,93,98,99 were free of selective reporting; one study65 was sorted as “no” due to an incomplete outcome measurement report that had been registered in protocol; the others were unclear because such details were not found. Of the 91 trials that provided the information on other bias, 77 studies18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,72,73,74,75,76,79,80,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,99,101,103,104,105,109,111 were free of other bias; 14 studies57,58,59,69,78,81,82,90,98,102,106,107,108,110 were assessed as “no” due to the statistical differences in baseline variables regarding as the most important prognosis. The details on the risk of bias studies were summarized in Table 2.

Credibility of blinding

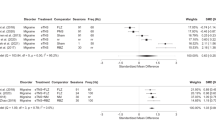

Only 24 out of the 94 studies reported the credibility of blinding in participants by conducting the creditability test in six types of sham EA methods. Twenty-three studies22,23,25,34,36,45,52,57,59,60,63,65,72,81,88,97,102,103,105,106,107,108,110 proved to be successful and one study66 proved to be failure. All six types of sham EA methods were claimed to be successful in blinding. They are sham EA type A (10/24 with 1 failure)22,60,66,81,97,102,103,106,108,110, type B (5/24)23,59,65,88,105, type Q (5/24)25,34,36,52,107, sham EA type O (2/24)45,57, sham EA type D (1/24)72, and sham EA type N (1/24)63.

Efficacy results of the included studies

All 94 studies involving 105 comparisons of real and sham EA groups provided the information for between-groups analyses. Among them, 59 real EA groups18,19,21,22,24,28,30,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,48,49,51,53,54,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,69,70,71,72,73,75,77,78,79,83,84,86,87,88,90,91,92,94,95,97,99,100,104,108 reported significant superiority over corresponding sham EA groups; forty-three real EA groups were not statistically better than sham EA groups; one study74 showed that sham EA group was superior to the real EA group; the remaining two studies50,111 lacked original data for between-groups analyses and were stated as “T > C?”. The efficacy results of the studies are listed in Table 1 and summarized in Table 3 according to different types of sham EA methods and EA indications.

Compared with sham EA controls, EA therapy in about 56.2% (59/105 comparisons) of comparisons reported the specific effect. Correspondingly, the real EA was superior to sham EA for type N (75%, 3/4 comparisons), type F (71.4%, 5/7 comparisons), type D (66.7%, 4/6 comparisons) and type M (66.7%, 2/3 comparisons). The lowest percentage of positive efficacy result was 44.4% (8/18 comparisons) in sham EA type L. The positive rate of efficacy for the three most often used sham EA methods were 50% (13/26 comparisons) for sham EA type A, 44.4% (8/18 comparisons) for sham EA type L and 64.3% (9/14 comparisons) for sham EA type O.

The type of sham EA methods varied across different EA indications. The sham EA type A was most commonly used in RCTs for pain, anesthesia and osteoarthritis. The sham EA type D and sham EA type Q were applied mainly in stroke studies. The sham EA type B was commonly applied to RCTs on depression. The sham EA type L and sham EA type O were commonly performed in trials on obesity. The sham EA type F and sham EA type L were commonly used in studies on primary dysmenorrhea.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic analysis to address sham EA methods in RCTs. The numbers of publications and sham EA methods have been increasing every decade. We summarized seventeen kinds of sham EA methods according to three aspects as needle location, depth of needle insertion and electrical stimulation, whereas only ten types of sham EA methods were identified from 94 included RCTs involving 6134 participants. The three predominant types of sham EA methods used were sham EA type A, type L and type O ordinally. Only 24 out of 94 trials reported credibility test with the results of 23 success and 1 failure using six types of sham EA methods mainly as follows: sham EA type A (10/24 with 1 failure), type B (5/24) and type Q (5/24). The remaining 3 sham EA methods were only tested in 4 trials. About 56.2% of comparisons provided the evidence of specific effect of EA therapy, and the four types of Sham EA controls with highest positive rate of efficacy result were type N (75%, 3/4 comparisons), type F (71.4%, 5/7 comparisons), type D (66.7%, 4/6 comparisons) and type M (66.7%, 2/3 comparisons) ordinally. However, all types of Sham EA controls were used in a small number of trials. Thus, the evidence was insufficient to recommend any type of sham EA control despite of the high positive rate. The sham EA control was frequently used in RCTs for pain, anesthesia, stroke, depression, obesity and primary dysmenorrheal/menstrual pain, suggesting that these diseases are particularly worthy of further EA RCTs.

The ideal design of sham acupuncture method remains methodologically challenging112. Consequently, a great variety of emerging sham acupuncture methods have found their ways into present RCTs by using non-traditional Chinese medicine acupoint26,27,113, no or superficial penetration29 and no or suboptimal stimulation28. The sham procedures in acupuncture RCTs were previously summarized by He et al.9 as seven types. A previous review by Dincer et al.8 reported the classification of sham acupuncture as sham type I~V based on three respects as needle location, insertion and stimulation. In the present study, we focused on the sham EA methods according to three aspects as needle location, depth of needle insertion and electrical stimulation, and summarized seventeen types of sham EA methods. Ten types of sham EA methods were actually used in the included RCTs.

The main purpose of RCTs on EA is to evaluate its specific effect. An optimal sham acupuncture technique must be biologically inactive and psychologically credible114. A lot of practice has been done to make the sham components of EA less perceptually and operationally distinguishable from real EA intervention for the purpose of keeping the blinding status of the participants. Streitberger needles, blunted needles and verum needles were frequently used with foam, tape or tube for hiding acupuncture loci from subjects18,19,21,22. Furthermore, a pricking sensation was elicited by dull tips for concealing the perceptual differences20,21,23,52,60,63,67,81. The sham EA device was often accompanied by indicator light or with sound signals for confusing the participants18,22,37. In the present study, six types of sham EA method were tested as concealable control in terms of blinding of participants.

The top three types of sham EA methods used were sham EA type A, type L and type O. The most frequently applied sham EA method was type A, accounting for a popular belief in its inertness based on its absence of key EA components as needle stimulation and electrical stimulation as well as its indistinguishable manipulation on same therapeutic acupoints. In the present study, the validation of credible participant blinding of this sham EA type was reported by most credibility tests. The debate emerged over the past decades over the inertness of non-penetrating procedure since the slight acupressure effects and physiological activity might be evoked by the tactile stimulation from blunt needle tips even without skin penetration112,115. Takayama et al.116 argued that non-penetrating placebo needle is at least clinically inert for pain alleviation based on their cross-over study reporting no analgesic effects of the skin-touch placebo needle over that of the no-touch placebo or that of the no-treatment control. However, conclusive evidence are out of our awareness up to now whether non-penetrating but skin-touch placebo needle plays a specific therapeutic role in other medical condition. Thus, the sham EA type A may be an promising candidate control for further RCTs on analgesic effects of EA and relative further researches are called for in aspect of any other conditions.

Sham EA type Q is deemed to be the most inert type of sham EA control because it avoids all therapeutic components, which also probably makes this sham method perceptually and operationally distinguishable from real EA intervention and to some extent results in problematic credibility of blinding in participant. In the present study, the credibility of participant blinding of this sham EA type was endorsed by five studies with credibility test25,34,36,52,107. However, mechanical non-penetration can evoke brain responses in healthy subjects. Thus, controversy raised regarding whether this type of sham EA method is physiologically inert control117. Moreover, four-fifth of the studies were conducted on acupuncture naïve participants. There is a possibility that previous experience of acupuncture treatments might have an impact on present perception of verum and sham EA intervention, which should be rigorously controlled in EA RCTs to avoid bias from unblinding. With the informed consent lack of explicit information on the sham method, debates emerged over ethical acceptability of the study.

The second commonly used sham EA method was type L. It was found that the differential effects of real EA and sham EA, which were attributed to point location, was not consistent across studies and conditions within this sham EA type, suggesting that EA on non-acupoints might be efficacious as EA on therapeutic acupoints. Furthermore, the improvements from baseline were also observed by Sahin et al.26, Li et al.46 and Yu et al.43 The similar findings were previously presented by Moffet et al.118 showing that sham acupuncture at non-acupoints was as efficacious as true acupuncture. It seemed that in the above studies the specificity of acupoints does not exit and to some extent were in violation of traditional acupuncture theories. Li et al.46 stated that the specificity of acupoints was not present in EA treatment. However, Wang et al.79 argued for the specificity of acupoints in EA treatment based on the better effects of EA at acupoints than that at non-acupoints on certain clinical outcomes. From the heterogeneous evidence of acupoint specificity, no definitive conclusion could be drawn based on the paucity of available high-quality clinical trials119. The main issue in this sham EA type might lie in the accurate identification of non-acupoint rather than a rough location nearby traditional acupoint that might be responsible for specific effects, which rises the challenge of conducting appropriate sham control in EA clinical trials especially in the presence or absence of the mechanism of acupoint specificity and the consistency in finding actual point across the different practitioners. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether this type is a concealable control for participant blinding since this sham EA tested credibility in the present study. Therefore, it demonstrates that sham EA type L might not be adequately controlled from inert or concealable perspective only if the mechanisms of acupoints were explicitly explored or the validation of so-called non-acupoint was verified by further researches. Cautions should be taken for eliminating bias from this sham EA control type.

The third commonly used sham EA was type O. During the procedure, the shallow insertion was applied to simulate deep skin penetration and to ensure the blinding of participant. In the present study, the validation of participant blinding of this sham EA type was endorsed by two studies45,57. As for the issue of inertness, a few studies reported that sham EA control improved baseline in certain clinical parameters compared with conventional group32,46,56,57,58. Moffet et al.118 stated that shallow needling at non-acupoints might be as efficacious as real acupuncture. Lund et al.120 reported that minimal acupuncture based on superficial insertion was not a valid control from a physiological perspective. Hróbjartsson et al.121 held the view that sham EA type was not inert control from Chinese medicine perspective. A sham EA procedure with superficial needling at non-acupoints might have subliminal effects since the locations of points was nearby true acupoints or myotome. Moreover, it is likely that the superficial insertion was not consistently applied since the needling depth varied across differentacupoints on different body parts and the relatively deep insertions might be conducted for taking the weight of the attached electrodes. Thus, this sham EA type may be concealable control but far from inert control in RCTs for EA, unless the extent to which the sham procedure could be regarded as physiologically inert has been clarified.

In the present study, six types of sham EA method were reported as successful in blinding. However, further investigations are needed for confirmation, since half of the tested types of sham EA controls were reported in a small number of trials. It should be noted that studies included did not provide sufficient evidence of blinding in acupuncturist. Vase et al.122 stated that it was hard to get acupuncture intervention fully double-blinded. Although non-penetrating needle was previously reported as potential sham control to mask both participants and practitioners in acupuncture research123,124,125, a previous review demonstrated that the acupuncture intervention was not fully double-blinded122. New strategies should be implemented for the development of double-blind sham EA control in terms of both participants and acupuncturists.

RCTs are generally recognized as the gold standard for the efficacy of clinical interventions by excluding the non-specific effect via a placebo control126. However, one study reported that the effect of EA therapy was merely the non-specific effect63. In the present study, the number of real EA group with superiority to, no difference from and inferiority to corresponding sham EA group was 59, 43 and 1, respectively. Thus, more than half comparisons demonstrated that EA therapy existed specific effects. Within all types of sham EA methods, the highest effective rate were type N (75% 3/4 comparisons), type F (71.4%, 5/7 comparisons), type D (66.7%, 4/6 comparisons) and type M (66.7%, 2/3 comparisons) successively. Considering the small number of included studies within corresponding sham EA type, the evidence are still insufficient to recommend any type of sham EA control despite of the high positive rate.

In the present study, 43/105 comparisons reported that EA has no specific effects compared with sham EA controls20,23,24,25,26,27,29,31,32,36,39,43,44,45,46,47,52,55,56,58,63,66,67,68,76,80,81,82,85,89,93,96,98,101,102,103,105,106,107,109,110. For a reason, the extent to which the individual component of EA intervention plays its therapeutic influences on the final outcomes is not clear during clinical treatment7. The debate consequently emerges regarding the therapeutic inactivity of sham EA control which is partially comprised of real EA components, such as suboptimal manual or electrical stimulation110. The probability in the specific effects of EA may be reduced by the potential activity produced by sham EA control. On the other hand, EA is a complex intervention method. Its therapeutic effects consist of specific effects from needling and stimulation components as well as moderately large nonspecific effects, which means that the efficacy results of RCTs for EA are more likely to be influenced by a variety of factors, such as patient/practitioner interaction and patient expectations127,128. In the clinical use, EA may be more effective than manual acupuncture in some situations such as when strong, continued stimulation is required, and when treating pain, anesthesia, stroke, depression, obesity and primary dysmenorrhea/menstrual pain, suggesting that further RCTs with appropriate sham EA control are in need to verify the specific effects on above conditions.

There are several weaknesses in the present study. Firstly, the search and screen procedure were limited to randomized, parallel-controlled trials published in English. Thus, those trials with cross-over design or published in other than English language were omitted. Secondly, with the aim of evaluating the sham method in RCTs on EA, a generous criterion was established to select eligible studies. Therefore, it was not easy to examine the specific effect of EA by data synthesis from different outcomes and indications because of the heterogeneity of trials. Finally, the reported credibility test addressed blinding effects in participant rather than in both participant and acupuncturist. The credibility tests were not reported in all studies and the number of studies using sham EA types was small, and therefore the conclusion should be interpreted with cautions.

Conclusion

Ten types of sham EA methods were identified based on our scheme classification. Generally, sham EA type A, type L and type O were frequently used. Yet, further clinical trials are recommended to maintain standard methodology of concealable and inert placebo EA techniques. Only 24 out of 94 trials were reported as positive credibility test in six types of sham EA methods, where sham EA type A, type B and type Q were highly practiced. It is worthy to study further about the importance of concealable sham EA types. EA therapy in approximately, 56.2% of comparisons provided the specific effects. The four types of sham EA (N, F, D and M respectively) represented the highest positive rate of efficacy results. However, progressive evidences on specific effects are mandatory. The sham EA control was observed frequently in pain, anesthesia, stroke, depression, obesity and primary dysmenorrhea RCTs. Also, broader studies in these predominant diseases are advised.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, Z. et al. Sham Electroacupuncture Methods in Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci. Rep. 7, 40837; doi: 10.1038/srep40837 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Medical Research Council (1948). Streptomycin Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Br. Med. J. 2, 769–782 (1948).

Meldrum, M. L. A brief history of the randomized controlled trial. From oranges and lemons to the gold standard. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 14, 745–760 (2000).

Guidance for Industry Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials ICH Topic E9. (2003). Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/applic-demande/guide-ld/ich/efficac/e9-eng.php#fnb1-ref. (Accessed: 6th November 2015).

Boutron, I. et al. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 4, e61 (2007).

Gaw, A. C., Chang, L. W. & Shaw, L. C. Efficacy of acupuncture on osteoarthritic pain. A controlled, double-blind study. N. Engl. J. Med. 293, 375–378 (1975).

Hammerschlag, R. et al. Randomized Controlled Trials of Acupuncture (1997–2007): An Assessment of Reporting Quality with a CONSORT- and STRICTA-Based Instrument. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 183910 (2011).

Langevin, H. M. et al. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 180805 (2011).

Dincer, F. & Linde, K. Sham interventions in randomized clinical trials of acupuncture–a review. Complement. Ther. Med. 11, 235–242 (2003).

He, W. et al. Review of controlled clinical trials on acupuncture versus sham acupuncture in Germany. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 33, 403–407 (2013).

Zhang, C. S., Yang, A. W., Zhang, A. L., May, B. H. & Xue, C. C. Sham control methods used in ear-acupuncture/ear-acupressure randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 20, 147–161 (2014).

Liu, A. J. et al. Electroacupuncture for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Chin. Med. 43, 1541–1566 (2015).

Wang, W. W., Xie, C. L., Lu, L. & Zheng, G. Q. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Baihui (GV20)-based scalp acupuncture in experimental ischemic stroke. Sci. Rep. 4, 3981 (2014).

Mayor, D. An exploratory review of the electroacupuncture literature: clinical applications and endorphin mechanisms. Acupunct. Med. 31, 409–415 (2013).

Fukazawa, Y., Maeda, T. & Kishioka, S. The pharmacological mechanisms of electroacupuncture. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 10, 62–69 (2009).

Kreiner, M., Zaffaroni, A., Alvarez, R. & Clark, G. Validation of a simplified sham acupuncture technique for its use in clinical research: a randomised, single blind, crossover study. Acupunct. Med. 28, 33–36 (2010).

Tough, E. A., White, A. R., Richards, S. H., Lord, B. & Campbell, J. L. Developing and validating a sham acupuncture needle. Acupunct. Med. 27, 118–122 (2009).

Lee, H. et al. Non-penetrating sham needle, is it an adequate sham control in acupuncture research? Complement. Ther. Med. 19 Suppl 1, S41–48 (2011).

Ntritsou, V. et al. Effect of perioperative electroacupuncture as an adjunctive therapy on postoperative analgesia with tramadol and ketamine in prostatectomy: a randomised sham-controlled single-blind trial. Acupunct. Med. 32, 215–222 (2014).

Chu, W. C. et al. Does acupuncture therapy alter activation of neural pathway for pain perception in irritable bowel syndrome?: a comparative study of true and sham acupuncture using functional magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 18, 305–316 (2012).

Wang, K., Bugge, J. & Bugge, S. A randomised, placebo-controlled trial of manual and electrical acupuncture for the treatment of tinnitus. Complement. Ther. Med. 18, 249–255 (2010).

Zyloney, C. E. et al. Imaging the functional connectivity of the Periaqueductal Gray during genuine and sham electroacupuncture treatment. Mol. Pain. 6, 80 (2010).

Jubb, R. W. et al. A blinded randomised trial of acupuncture (manual and electroacupuncture) compared with a non-penetrating sham for the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee. Acupunct. Med. 26, 69–78 (2008).

Chung, K. F. et al. Randomized non-invasive sham-controlled pilot trial of electroacupuncture for postpartum depression. J. Affect. Disord. 142, 115–121 (2012).

Barlas, P., Ting, S. L., Chesterton, L. S., Jones, P. W. & Sim, J. Effects of intensity of electroacupuncture upon experimental pain in healthy human volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain 122, 81–89 (2006).

Wayne, P. M. et al. Acupuncture for upper-extremity rehabilitation in chronic stroke: a randomized sham-controlled study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86, 2248–2255 (2005).

Sahin, N., Ozcan, E., Sezen, K., Karatas, O. & Issever, H. Efficacy of acupunture in patients with chronic neck pain–a randomised, sham controlled trial. Acupunct. Electrother. Res. 35, 17–27 (2010).

Fanti, L. et al. Electroacupuncture analgesia for colonoscopy. a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98, 312–316 (2003).

Hsing, W. T., Imamura, M., Weaver, K., Fregni, F. & Azevedo Neto, R. S. Clinical effects of scalp electrical acupuncture in stroke: a sham-controlled randomized clinical trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 18, 341–346 (2012).

Gosman-Hedstrom, G. et al. Effects of acupuncture treatment on daily life activities and quality of life: a controlled, prospective, and randomized study of acute stroke patients. Stroke 29, 2100–2108 (1998).

Jing, C. et al. Electro-acupuncture versus sham electro-acupuncture for auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 23, 579–588 (2009).

Kong, J. et al. An fMRI study on the interaction and dissociation between expectation of pain relief and acupuncture treatment. NeuroImage 47, 1066–1076 (2009).

Darbandi, S. et al. Effects of body electroacupuncture on plasma leptin concentrations in obese and overweight people in Iran: a randomized controlled trial. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 19, 24–31 (2013).

Yang, C., An, L., Han, R., Kang, X. & Wang, B. Effects of combining electroacupuncture with general anesthesia induced by sevoflurane in patients undergoing supratentorial craniotomy and improvements in their clinical recovery profile & blood enkephalin. Acupunct. Electrother. Res. 37, 125–138 (2012).

Liu, Y., Liu, L. & Wang, X. Electroacupuncture at points Baliao and Huiyang (BL35) for post-stroke detrusor overactivity. Neural. Regen. Res. 8, 1663–1672 (2013).

Zhang, Z. et al. Electroacupuncture at ST36 accelerates the recovery of gastrointestinal motility after colorectal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct. Med. 32, 223–226 (2014).

Mao, J. J. et al. Electroacupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: a randomized trial. Cancer 120, 3744–3751 (2014).

Leung, W. W., Jones, A. Y., Ng, S. S., Wong, C. Y. & Lee, J. F. Electroacupuncture in reduction of discomfort associated with barostat-induced rectal distension–a randomized controlled study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 660–666 (2011).

Rusy, L. M., Hoffman, G. M. & Weisman, S. J. Electroacupuncture prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting following pediatric tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. Anesthesiology 96, 300–305 (2002).

Yang, M. et al. Electroacupuncture stimulation at sub-specific acupoint and non-acupoint induced distinct brain glucose metabolism change in migraineurs: a PET-CT study. J. Transl. Med. 12, 351 (2014).

Chen, H. et al. Electroacupuncture treatment for pancreatic cancer pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pancreatology 13, 594–597 (2013).

Quispe-Cabanillas, J. G. et al. Impact of electroacupuncture on quality of life for patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis under treatment with immunomodulators: a randomized study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 209 (2012).

Aranha, M. F., Muller, C. E. & Gaviao, M. B. Pain intensity and cervical range of motion in women with myofascial pain treated with acupuncture and electroacupuncture: a double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 19, 34–43 (2015).

Yu, D. T. & Jones, A. Y. Physiological changes associated with de qi during electroacupuncture to LI4 and LI11: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Acupunct. Med. 31, 143–150 (2013).

Li, S. et al. Randomized-controlled study of treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder of preschool children with combined electro-acupuncture and behavior therapy. Complement. Ther. Med. 18, 175–183 (2010).

Zheng, Z. et al. The effect of electroacupuncture on opioid-like medication consumption by chronic pain patients: a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Pain 12, 671–676 (2008).

Li, G., Li, S., Wang, B. & An, L. The effect of electroacupuncture on postoperative immunoinflammatory response in patients undergoing supratentorial craniotomy. Exp. Ther. Med. 6, 699–702 (2013).

Lin, J. G. et al. The effect of high and low frequency electroacupuncture in pain after lower abdominal surgery. Pain 99, 509–514 (2002).

Chen, C. Y. et al. The influence of electro-acupuncture stimulation to female constipation patients. Am. J. Chin. Med. 41, 301–313 (2013).

Schukro, R. P., Heiserer, C., Michalek-Sauberer, A., Gleiss, A. & Sator-Katzenschlager, S. The effects of auricular electroacupuncture on obesity in female patients–a prospective randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Complement. Ther. Med. 22, 21–25 (2014).

Yu, J. B. et al. Effect of electroacupuncture at Zusanli (ST36) and Sanyinjiao (SP6) acupoints on adrenocortical function in etomidate anesthesia patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 20, 406–412 (2014).

Xie, Y. H., Chai, X. Q., Wang, Y. L., Gao, Y. C. & Ma, J. Effect of electro-acupuncture stimulation of Ximen (PC4) and Neiguan (PC6) on remifentanil-induced breakthrough pain following thoracal esophagectomy. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 34, 569–574 (2014).

Sim, C. K., Xu, P. C., Pua, H. L., Zhang, G. & Lee, T. L. Effects of electroacupuncture on intraoperative and postoperative analgesic requirement. Acupunct. Med. 20, 56–65 (2002).

Song, C., Halbreich, U., Han, C., Leonard, B. E. & Luo, H. Imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and between Th1 and Th2 cytokines in depressed patients: the effect of electroacupuncture or fluoxetine treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry 42, 182–188 (2009).

Shafshak, T. S. Electroacupuncture and exercise in body weight reduction and their application in rehabilitating patients with knee osteoarthritis. Am. J. Chin. Med. 23, 15–25 (1995).

Pastore, L. M., Williams, C. D., Jenkins, J. & Patrie, J. T. True and sham acupuncture produced similar frequency of ovulation and improved LH to FSH ratios in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 3143–3150 (2011).

Naslund, J., Naslund, U. B., Odenbring, S. & Lundeberg, T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) for the treatment of idiopathic anterior knee pain. J. Rehabil. Med. 34, 231–238 (2002).

Shen, J. et al. Electroacupuncture for control of myeloablative chemotherapy-induced emesis: A randomized controlled trial. J. A. M. A. 284, 2755–2761 (2000).

Wyon, Y., Wijma, K., Nedstrand, E. & Hammar, M. A comparison of acupuncture and oral estradiol treatment of vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Climacteric 7, 153–164 (2004).

Zhang, Z. J. et al. Dense cranial electroacupuncture stimulation for major depressive disorder–a single-blind, randomized, controlled study. PloS One 7, e29651 (2012).

Zheng, Z. et al. Acupuncture analgesia for temporal summation of experimental pain: a randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Pain 14, 725–731 (2010).

Ma, Y. X. et al. A comparative study on the immediate effects of electroacupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6), Xuanzhong (GB39) and a non-meridian point, on menstrual pain and uterine arterial blood flow, in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Pain Med. 11, 1564–1575 (2010).

Wang, B. H. et al. Selection of acupoints for managing upper-extremity spasticity in chronic stroke patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 9, 147–156 (2014).

Yeung, W. F. et al. Electroacupuncture for residual insomnia associated with major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 34, 807–815 (2011).

Chan, Y. Y. et al. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture as an adjunct to methadone treatment services for heroin addicts: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Chin. Med. 42, 569–586 (2014).

Man, S. C. et al. A pilot controlled trial of a combination of dense cranial electroacupuncture stimulation and body acupuncture for post-stroke depression. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 14, 255 (2014).

Oh, B. et al. Acupuncture for treatment of arthralgia secondary to aromatase inhibitor therapy in women with early breast cancer: pilot study. Acupunct. Med. 31, 264–271 (2013).

Wong, R. H. et al. Analgesic effect of electroacupuncture in postthoracotomy pain: a prospective randomized trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 81, 2031–2036 (2006).

Song, Y., Zhou, D., Fan, J., Luo, H. & Halbreich, U. Effects of electroacupuncture and fluoxetine on the density of GTP-binding-proteins in platelet membrane in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 98, 253–257 (2007).

Cameron, I. D., Wang, E. & Sindhusake, D. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture and simulated acupuncture for subacute and chronic whiplash. Spine 36, E1659–1665 (2011).

Darbandi, M. et al. Auricular or body acupuncture: which one is more effective in reducing abdominal fat mass in Iranian men with obesity: a randomized clinical trial. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 13, 92 (2014).

Wei, L., Wang, H., Han, Y. & Li, C. Clinical observation on the effects of electroacupuncture at Shaoze (SI 1) in 46 cases of postpartum insufficient lactation. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 28, 168–172 (2008).

Wang, S. M., Punjala, M., Weiss, D., Anderson, K. & Kain, Z. N. Acupuncture as an adjunct for sedation during lithotripsy. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 13, 241–246 (2007).

Kvorning, N., Christiansson, C. & Akeson, J. Acupuncture facilitates neuromuscular and oculomotor responses to skin incision with no influence on auditory evoked potentials under sevoflurane anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 47, 1073–1078 (2003).

Kvorning, N., Christiansson, C., Beskow, A., Bratt, O. & Akeson, J. Acupuncture fails to reduce but increases anaesthetic gas required to prevent movement in response to surgical incision. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 47, 818–822 (2003).

Yang, L. et al. Cardioprotective effects of electroacupuncture pretreatment on patients undergoing heart valve replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 89, 781–786 (2010).

Sahmeddini, M. A., Farbood, A. & Ghafaripuor, S. Electro-acupuncture for pain relief after nasal septoplasty: a randomized controlled study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 16, 53–57 (2010).

Wang, W. et al. Study on the regulatory effect of electro-acupuncture on hegu point (LI4) in cerebral response with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 13, 10–16 (2007).

Jia, C. S. et al. Electroacupuncture at Qiuxu (GB 40) for treatment of migraine–a clinical multicentral random controlled study. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 29, 43–49 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. Electroacupuncture for moderate and severe benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized controlled trial. PloS One 8, e59449 (2013).

Andreescu, C., Glick, R. M., Emeremni, C. A., Houck, P. R. & Mulsant, B. H. Acupuncture for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72, 1129–1135 (2011).

Yeung, W. F., Chung, K. F., Zhang, S. P., Yap, T. G. & Law, A. C. Electroacupuncture for primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 32, 1039–1047 (2009).

Chen, W. T., Chang, F. C., Chen, Y. H. & Lin, J. G. An Evaluation of Electroacupuncture at the Weizhong Acupoint (BL-40) as a Means of Relieving Pain Induced by Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 592319 (2014).

Wang, C. P., Kao, C. H., Chen, W. K., Lo, W. Y. & Hsieh, C. L. A single-blinded, randomized pilot study evaluating effects of electroacupuncture in diabetic patients with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 14, 833–839 (2008).

Meissner, W. et al. Acupuncture decreases somatosensory evoked potential amplitudes to noxious stimuli in anesthetized volunteers. Anesth. Analg. 98, 141–147 (2004).

Zhou, S. et al. Bilateral effects of 6 weeks’ unilateral acupuncture and electroacupuncture on ankle dorsiflexors muscle strength: a pilot study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93, 50–55 (2012).

Yeh, B. Y. et al. Effect of electroacupuncture in postanesthetic shivering during regional anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 233 (2012).

Yu, J. S., Shen, K. H., Chen, W. C., Her, J. S. & Hsieh, C. L. Effects of electroacupuncture on benign prostate hyperplasia patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 303198 (2011).

Ma, W. et al. Effects of Sanyinjiao (SP6) with electroacupuncture on labour pain in women during labour. Complement. Ther. Med. 19 Suppl 1, S13–18 (2011).

Li, G., Li, S., An, L. & Wang, B. Electroacupuncture alleviates intraoperative immunosuppression in patients undergoing supratentorial craniotomy. Acupunct. Med. 31, 51–56 (2013).

Deluze, C., Bosia, L., Zirbs, A., Chantraine, A. & Vischer, T. L. Electroacupuncture in fibromyalgia: results of a controlled trial. B. M. J. 305, 1249–1252 (1992).

Ng, S. S. et al. Electroacupuncture reduces duration of postoperative ileus after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 144, 307–313.e301 (2013).

Lee, S. H. & Lee, B. C. Electroacupuncture relieves pain in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: three-arm randomized trial. Urology 73, 1036–1041 (2009).

Tam, L. S., Leung, P. C., Li, T. K., Zhang, L. & Li, E. K. Acupuncture in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind controlled pilot study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 7, 35 (2007).

Kvorning, N. & Akeson, J. Plasma adrenaline increases in anesthetized patients given electro-acupuncture before surgery. Pain Med. 11, 1126–1131 (2010).

Waite, N. R. & Clough, J. B. A single-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a simple acupuncture treatment in the cessation of smoking. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 48, 1487–1490 (1998).

Holzer, A. et al. Auricular acupuncture for postoperative pain after gynecological surgery: a randomized controlled trail. Minerva Anestesiol. 77, 298–304 (2011).

Sator-Katzenschlager, S. M. et al. Auricular electro-acupuncture as an additional perioperative analgesic method during oocyte aspiration in IVF treatment. Hum. Reprod. 21, 2114–2120 (2006).

Liu, C. Z. et al. Immediate analgesia effect of single point acupuncture in primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 12, 300–307 (2011).

Liu, C. Z. et al. A randomized controlled trial of single point acupuncture in primary dysmenorrhea. Pain Med. 15, 910–920 (2014).

Maeda, Y. et al. Acupuncture-evoked response in somatosensory and prefrontal cortices predicts immediate pain reduction in carpal tunnel syndrome. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 795906 (2013).

Shi, G. X. et al. Effects of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6) on prostaglandin levels in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Clin. J. Pain 27, 258–261 (2011).

Dias, M. et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on local anaesthesia for inguinal hernia repair: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Acupunct. Med. 28, 65–70 (2010).

Zhang, S. P., Chiu, T. T. & Chiu, S. N. Long-term efficacy of electroacupuncture for chronic neck pain: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med. J. 19 Suppl 9, 36–39 (2013).

Sangdee, C. et al. Electroacupuncture versus diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2, 3 (2002).

Johansson, B. B. et al. Acupuncture and transcutaneous nerve stimulation in stroke rehabilitation: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 32, 707–713 (2001).

Hopwood, V., Lewith, G., Prescott, P. & Campbell, M. J. Evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture in defined aspects of stroke recovery: a randomised, placebo controlled single blind study. J. Neurol. 255, 858–866 (2008).

White, A. R., Resch, K. L. & Ernst, E. Randomized trial of acupuncture for nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 2251–2255 (1998).

Dias, M., Vellarde, G. C., Olej, B., Teofilo Salgado, A. E. & de Barros Rezende, I. Effects of electroacupuncture on stress-related symptoms in medical students: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Acupunct. Med. 32, 4–11 (2014).

Lin, R. T. et al. Electroacupuncture and rosiglitazone combined therapy as a means of treating insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 969824 (2013).

Michalek-Sauberer, A. et al. Perioperative auricular electroacupuncture has no effect on pain and analgesic consumption after third molar tooth extraction. Anesth. Analg. 104, 542–547 (2007).

Carlsson, C. P. & Sjolund, B. H. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study with long-term follow-up. Clin. J. Pain 17, 296–305 (2001).

Lund, I. & Lundeberg, T. Are minimal, superficial or sham acupuncture procedures acceptable as inert placebo controls? Acupunct. Med. 24, 13–15 (2006).

Bäcker, M. et al. Acupuncture in migraine: investigation of autonomic effects. Clin. J. Pain 24, 106–115 (2008).

Vickers, A. J. Placebo controls in randomized trials of acupuncture. Eval. Health Prof. 25, 421–435 (2002).

Lundeberg, T., Lund, I., Näslund, J. & Thomas, M. The Emperors sham - wrong assumption that sham needling is sham. Acupunct. Med. 26, 239–242 (2008).

Takayama, M. et al. Is Skin-Touch Sham Needle Not Placebo? A Double-Blind Crossover Study on Pain Alleviation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 152086 (2015).

Dhond, R. P., Witzel, T., Hämäläinen, M., Kettner, N. & Napadow, V. Spatiotemporal mapping the neural correlates of acupuncture with MEG. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 14, 679–688 (2008).

Moffet, H. H. Sham acupuncture may be as efficacious as true acupuncture: a systematic review of clinical trials. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 213–216 (2009).

Zhang, H., Bian, Z. & Lin, Z. Are acupoints specific for diseases? A systematic review of the randomized controlled trials with sham acupuncture controls. Chin. Med. 5, 1 (2010).

Lund, I., Naslund, J. & Lundeberg, T. Minimal acupuncture is not a valid placebo control in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture: a physiologist’s perspective. Chin. Med. 4, 1 (2009).

Hrobjartsson, A. & Gotzsche, P. C. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD003974 (2010).

Vase, L. et al. Can acupuncture treatment be double-blinded? An evaluation of double-blind acupuncture treatment of postoperative pain. PLoS One 10, e0119612 (2015).

Takakura, N., Takayama, M., Kawase, A. & Yajima, H. Double blinding with a new placebo needle: a validation study on participant blinding. Acupunct. Med. 29, 203–207 (2011).

Takakura, N. & Yajima, H. A double-blind placebo needle for acupuncture research. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 7, 31 (2007).

Takakura, N., Takayama, M., Kawase, A., Kaptchuk, T. J. & Yajima, H. Double-blind acupuncture needle: a potential tool to investigate the nature of pain and pleasure. ISRN Pain 2013 (2013).

Meldrum, M. L. A brief history of the randomized controlled trial. From oranges and lemons to the gold standard. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 14, 745–760 (2000).

Linde, K., Niemann, K., Schneider, A. & Meissner, K. How large are the nonspecific effects of acupuncture? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med. 8, 75 (2010).

Kaptchuk, T. J. et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. B. M. J. 336, 999–1003 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by grant of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81573750/81473491/81173395/H2902), the Young and Middle-Aged University Discipline Leaders of Zhejiang Province, China (2013277); Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-level Health talents (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-X.C., Y.L., X.-G.Z., S.C., W.-T.Y., X.-W.Z. and G.-Q.Z. participated in its design, searched databases, extracted and assessed studies and drafted the manuscript. Z.-X.C., Y.L., X.-G.Z., S.C., W.-T.Y., and X.-W.Z. analyzed data and carried out the statistical analysis. G.-Q.Z. acted as an arbitrator in the review. G.-Q.Z. conceived and designed the article, supervised the study and contributed to finalize the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Zx., Li, Y., Zhang, Xg. et al. Sham Electroacupuncture Methods in Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci Rep 7, 40837 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40837

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40837

This article is cited by

-

Electroacupuncture regulates the P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammatory cascade to relieve decreased sensation on ocular surface of type 2 diabetic rats with dry eye

Purinergic Signalling (2024)

-

Effectiveness of electroacupuncture for thin endometrium in infertile women: study protocol for a single-blind, randomized controlled trial

Trials (2021)

-

Acupuncture as adjunctive therapy for acute renal colic caused by urinary calculi: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

Trials (2021)

-

Acupuncture is ineffective for chronic low back pain? A critical analysis and rethinking

Frontiers of Medicine (2021)

-

Acupuncture for persistent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial

Trials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.