Abstract

To evaluate the efficacy of pirfenidone in patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RPILD) related to clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), we conducted an open-label, prospective study with matched retrospective controls. Thirty patients diagnosed with CADM-RPILD with a disease duration <6 months at Renji Hospital South Campus from June 2014 to November 2015 were prospectively enrolled and treated with pirfenidone at a target dose of 1800 mg/d in addition to conventional treatment, such as a glucocorticoid and/or other immunosuppressants. Matched patients without pirfenidone treatment (n = 27) were retrospectively selected as controls between October 2012 and September 2015. We found that the pirfenidone add-on group displayed a trend of lower mortality compared with the control group (36.7% vs 51.9%, p = 0.2226). Furthermore, the subgroup analysis indicated that the pirfenidone add-on had no impact on the survival of acute ILD patients (disease duration <3 months) (50% vs 50%, p = 0.3862); while for subacute ILD patients (disease duration 3–6 months), the pirfenidone add-on (n = 10) had a significantly higher survival rate compared with the control subgroup (n = 9) (90% vs 44.4%, p = 0.0450). Our data indicated that the pirfenidone add-on may improve the prognosis of patients with subacute ILD related to CADM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a common complication of dermatomyositis (DM) with a prevalence rate as great as 65% and is considered a key prognostic factor1. Clinical amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), which is a special phenotype of DM with characteristic cutaneous manifestations but no or only subclinical myopathy2. Many studies, mainly from Asia, including ours, have demonstrated that patients with CADM tend to develop rapidly progressive ILD (RPILD) and have a poor response to conventional therapy, such as high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants, leading to lethal outcomes with a 6-month survival rate of less than 50%3,4,5.

Pirfenidone, a new oral antifibrotic agent, has been approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Randomized controlled trials of pirfenidone in patients with IPF suggested that it could ameliorate pulmonary function decline and improve progression-free survival6,7,8. Its utility in ILD related to connective tissue disease (CTD) has been implicated9, but no evidence has yet demonstrated its efficacy. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the possible therapeutic effects of pirfenidone on RPILD associated with CADM.

Results

The baseline clinical features of the pirfenidone add-on group (n = 30) and the matched control group (n = 27) are summarized in Table 1.

Outcomes

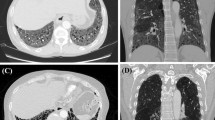

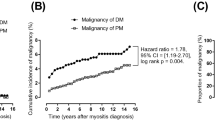

The analysis of all-cause mortality in all patients showed fewer deaths in the pirfenidone add-on group than in the control group, although the difference was not significant (36.7% vs 51.9%, p = 0.2226) (Fig. 1A). After dividing the patients into two subgroups according to the duration of ILD, the pirfenidone add-on had no impact on the survival of patients with acute ILD (disease duration <3 months) (50% vs 50%, p = 0.3862) (Fig. 1B); while in patients with subacute ILD (disease duration between 3–6 months), the pirfenidone add-on (n = 10) achieved a significantly higher survival rate compared with the control subgroup (n = 9) (90% vs 44.4%, p = 0.0450) (Fig. 1C). The baseline HRCT scores were not different between the groups, which further suggested the matching quality of the controls (Fig. 2). However, no additional gain in the HRCT score improvement was observed among the survivors who received pirfenidone compared to the control survivors. Changes in the %FVC were not analyzed because up to 36.8% of the baseline data were unavailable owing to the severity of the respiratory failure of these patients. Among 26 serum samples available from pirfenidone add-on group, 84.6% displayed a positive anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 autoantibody (anti-MDA-5 Ab) reaction. In retrospective control group, only limited serum samples were available (n = 7) with a positivity of anti-MDA-5 Ab at 57.1% (p = 0.145). Moreover, in pirfenidone add-on group, the positivity of anti-MDA-5 Ab had no significant difference between survivor and deceased (80.0% vs 90.9%, p = 0.617).

The survival curves of the pirfenidone add-on group and the control group.

(A) Survival analysis of all patients showed that the pirfenidone add-on group had fewer deaths than the control group, but the difference was not significant. (B) The pirfenidone add-on had no impact on the survival of patients with acute ILD (disease duration <3 months). (C) The pirfenidone add-on led to a significantly higher survival rate in subacute ILD patients (disease duration 3–6 months) compared with the control subgroup.

Safety

No direct pirfenidone-related serious adverse events occurred during follow-up. The elevations of hepatic enzyme (30%) and gastrointestinal reaction (13.3%) were common, but most of these events were mild to moderate in severity and were reversible. Three adverse events (10%) led to treatment discontinuation in 3 survivors (2 patients with acute ILD and 1 patient with subacute ILD) and were elevated hepatic enzyme levels, rash and diarrhea.

Discussion

According to our previous retrospective cohort study5, the rate of ILD in DM is as high as 50%. As a subtype of DM, CADM patients appear to be at a higher risk of developing rapidly progressive ILD, especially in the presence of the anti-MDA-5 antibody10,11. Most of the patients with CADM-RPILD are resistant to intensive therapy, such as high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents, resulting in over 50% mortality rate2,3,4,5. Cyclosporin alone or combined with cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, rituximab, basiliximab, or polymyxin B hemoperfusion has been used in case reports or small case series with undetermined efficacy12,13,14,15,16,17.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to investigate the efficacy of pirfenidone on CADM-RPILD patients. Among the pirfenidone add-on group, 84.6% were anti-MDA-5 autoantibody positive, which is the most representative poor prognostic marker. It has been well conceived that anti-MDA-5 antibody is strongly associated with the development of rapidly progressive, fatal ILD in CADM patients10,11,18. Our data indicated that the pirfenidone add-on probably has no impact on the survival of such high risk patients with acute ILD related to CADM; however, for patients with subacute ILD (disease duration between 3–6 months), pirfenidone may help suppress the disease progression and, ultimately, improve the outcome. It is noteworthy that it will take weeks and up to 3 months for pirfenidone to exert its therapeutic effects in chronic IPF. Its “slow-acting” antifibrotic property could be insufficient in the context of acute phases of lung injury, which is in line with the observation that pirfenidone is incapable of decreasing the risk of acute IPF exacerbation19. Moreover, according to our data, anti-MDA-5 autoantibody is apparently not an indicator of pirfenidone’s response as positivity for the antibody did not significantly differ between the survivor and deceased patients treated with pirfenidone (80.0% vs 90.9%, p = 0.617). In other words, it seems that only the slope of ILD progression and the phase of pathophysiology that matters. Future treatments should be developed, based on a staged approach and a timing strategy, in order to significantly change the course of this high risk disease.

The results of our study should be interpreted cautiously owing to certain limitations. First, this study was a single-center, open-label trial, and the control patients were not prospectively randomized. Second, the sample size was limited, especially for the subgroup analysis. Therefore, a multi-centered, randomized, control trial on pirfenidone targeting patients with subacute ILD secondary to CADM is needed.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This was a mono-centered, open-label, prospective study with matched retrospective controls. All patients fulfilled the provisional diagnosis of CADM according to the modified Sontheimer’s criteria2 and our previous definitions5. RPILD is defined as disease exacerbation within 6 months of the onset of ILD, presenting as increased levels of dyspnea and worsening of fibrosis on pulmonary HRCT with >10% increase of the HRCT score and/or a reduction in %FVC by >10% of the absolute value. Patients previously treated with biologics, including basiliximab, and patients with malignancy-associated CADM or other connective tissue disease comorbidities or with alanine transaminase levels greater than 2 times the upper normal limits were excluded.

After providing written informed consent, 30 adult patients who met the criteria between June 2014 and November 2015 at the Shanghai Renji Hospital South Campus received treatment with pirfenidone in addition to the institutional standard of care, which includes a glucocorticoid and/or immunosuppressant. Pirfenidone was administered in three divided doses (200 mg tid) and was increased to the manufacturer’s instructed target dose (600 mg tid) over a 2-week period. The maximum dose was maintained throughout the study in patients who tolerated it. Pulmonary function tests (except for cases in which the patient’s respiratory failure was too severe to perform the measurement) were performed at the start of treatment and every month thereafter. All patients underwent HRCT to assess the progression of ILD before the start of the treatment and then underwent HRCT every three months (unless there was acute exacerbation, which was determined by the investigator). The overall HRCT score was calculated based on the classification by Ichikado20. Matched patients meeting the same aforementioned criteria received only the institutional standard of care between October 2012 and September 2015 and were retrospectively enrolled as the control group21. All possible confounders, including age, gender, disease duration, the HRCT score (as a surrogate of disease severity), smoking history, exposure to a glucocorticoid or other immunosuppressant, or the use of antimicrobial/antifungal agents, were balanced using the covariance matrix of a Cox regression model. To avoid selection bias, the investigators in charge of the matched-control selection were blinded to the outcomes of each patient.

Serum anti-MDA-5 autoantibody was measured by an immune blot assay (EuroImmune, Lubeck, Germany). Briefly, each MDA5-transferred nitrocellulose strip was incubated in sample buffer on a shaker for 5 minutes at room temperature (RT) and then was incubated with the human serum sample diluted in blocking buffer for 30 minutes at RT. After washing 3 times, phosphatase alkaline-labeled goat anti-human IgG antibody was added to each strip and incubated for 30 minutes at RT. Then the strips were washed 3 times, and the phosphatase reagent, used to develop the color, was added for 10 minutes at RT before another wash. Based on the signal intensity, the results were classified as negative or positive. Krebs von den lungen-6 (KL-6), as a lung fibrosis marker, was measured by the chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay LUMIPULSE KL-6 using a KL-6 antibody (EIDIA Co., Ltd, JPN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The primary endpoint of the investigation was the changes in the 12-month survival rate from the onset of ILD. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Renji Hospital and is registered at Chictr.org (number: ChiCTR-IPR-16007958; date: Oct 21, 2015 (retrospective registration)).

Statistical analysis

The clinical data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons of the two groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test, the paired t-test, or Fisher’s exact test when indicated. The intent-to-treat analysis was performed in the survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier test. All statistical analyses were conducted in the SPSS 19.0 software package. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, T. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Sci. Rep. 6, 33226; doi: 10.1038/srep33226 (2016).

References

Marie, I. et al. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 47, 614–622 (2002).

Sontheimer, R. D. Would a new name hasten the acceptance of amyopathic dermatomyositis (dermatomyositissine myositis) as a distinctive subset within the idiopathic inflammatory dermatomyopathies spectrum of clinical illness? J Am Acad Dermatol 46, 626–636 (2002).

Sakamoto, N. et al. Nonspecific interstitialpneumonia with poor prognosis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. Intern Med 43, 838–842 (2004).

Yokoyama, T. et al. Fatal rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis and CD8 T lymphocytes. J Intensive Care Med 20, 160–163 (2005).

Ye, S. et al. Adult clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapid progressive interstitial lung disease: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 26, 1647–1654 (2007).

Taniguchi, H. et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a phase III clinical trial in Japan. Eur Respir J 35, 821–829 (2010).

Noble, P. W. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 377, 1760–1769 (2011).

King, T. E. Jr. et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 370, 2083–2092 (2014).

Miura, Y. et al. Clinical experience with pirfenidone in five patients with scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 31, 235–238 (2014).

Siamak, M. K. et al. Anti-MDA5 is associated with rapidly progressive lung disease and poor survival in U.S. patients with amyopathic and myopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Care Res 68, 689–694 (2015).

Ikeda, S. et al. Interstitial lung disease in clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with and without anti-MDA-5 antibody: to lump or split? BMC Pulm Med 15, 159–168 (2015).

Go, D. J. et al. Survival benefit associated with early cyclosporine treatment for dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatol Int 36, 125–131 (2016).

Kameda, H. et al. Combination therapy with corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide for acute/subacute interstitial pneumonia in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 32, 1719–1726 (2005).

Takashi, K. et al. The efficacy of tacrolimus in patients with interstitial lung diseases complicated with polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 54, 39–44 (2015).

Koichi, Y. et al. A case of anti-MDA5-positive rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in a patient with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis ameliorated by rituximab, in addition to standard immunosuppressive treatment. Mod Rheumatol 12, 1–5 (2015).

Zou, J. et al. Basiliximab may improve the survival rate of rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Ann Rheum Dis 73, 1591–1593 (2014).

Teruya, A. et al. Successful Polymyxin B Hemoperfusiontreatment associated with serial reduction of serum anti-CADM-140/MDA5 antibody levels in rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease with amyopathic dermatomyositis. Chest 144, 1934–1936 (2013).

Moises, L. H. et al. Anti-MDA5 Antibodies in a Large Mediterranean Population of Adults with Dermatomyositis. Journal of Immunology Research 2014, 290797 (2014).

Carlos, A., Gonzalo, L., Carmen, V., Alex, A. & Gabriel, R. Pirfenidone for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plos One 10, e0136160 (2015).

Ichikado, K. et al. Prediction of prognosis for acute respiratory distress syndrome with thin section CT: validation in 44 cases. Radiology 238, 321–329 (2006).

Koudstaal, J. et al. Obstetric outcome of twin pregnancies after in-vitro fertilization: a matched control study in four Dutch University hospitals. Human Reproduction 15, 935–940 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Beijing Contini pharmaceutical Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published. S.Y. and X.W. contributed to the conception and design, T.L., L.G., Z.C., L.G. and F.S. were involved to collect the data, T.L., L.G., X.T. and S.C. performed the analysis and interpretation of data. T.L. and L.G. contributed equally to this article.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Guo, L., Chen, Z. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Sci Rep 6, 33226 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33226

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33226

This article is cited by

-

Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis: pathogenesis and clinical progress

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2024)

-

Diagnosis and management of autoimmune diseases in the ICU

Intensive Care Medicine (2024)

-

Ground-glass opacity score predicts the prognosis of anti-MDA5 positive dermatomyositis: a single-centre cohort study

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

An observational study of clinical recurrence in patients with interstitial lung disease related to the antisynthetase syndrome

Clinical Rheumatology (2023)

-

“Management of myositis associated interstitial lung disease”

Rheumatology International (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.