Abstract

Vertical hot electron transistors incorporating atomically-thin 2D materials, such as graphene or MoS2, in the base region have been proposed and demonstrated in the development of electronic and optoelectronic applications. To the best of our knowledge, all previous 2D material-base hot electron transistors only considered applying a positive collector-base potential (VCB > 0) as is necessary for the typical unipolar hot-electron transistor behavior. Here we demonstrate a novel functionality, specifically a dual-mode operation, in our 2D material-base hot electron transistors (e.g. with either graphene or MoS2 in the base region) with the application of a negative collector-base potential (VCB < 0). That is, our 2D material-base hot electron transistors can operate in either a hot-electron or a reverse-current dominating mode depending upon the particular polarity of VCB. Furthermore, these devices operate at room temperature and their current gains can be dynamically tuned by varying VCB. We anticipate our multi-functional dual-mode transistors will pave the way towards the realization of novel flexible 2D material-based high-density and low-energy hot-carrier electronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 1960, ballistic hot electron transistors (HETs) have been vigorously researched and implemented in diverse material systems (e.g. cold cathode transistor exploiting a thin metal base1,2, planar doped barrier transistor incorporating III-V compound semiconductors3, two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG)-based HETs4,5,6, etc.) for their potential in high-speed applications. Analogous in design to a bipolar transistor, HETs are comprised of an emitter, base, and collector. However, various properties of the injected ballistic hot electrons, such as their initial velocity, higher kinetic energy, and quasi-mono-energetic distribution upon injection via quantum tunneling, differ from the diffusive transport in bipolar transistors2,7. In HETs, the ballistic hot electrons are injected through a thin tunnel barrier separating the emitter from the base, and a portion of these hot electrons are collected upon traversing a filter barrier at the base-collector junction (e.g. contribute towards the on-state collector current).

Furthermore, the cutoff frequency of HETs is primarily governed by the base thickness and the resistances and capacitances of the emitter and collector regions. To this end, various bulk semiconductor heterostructures, such as InGaAs/InP and AlGaAs/GaAs, have been precisely engineered with undoped and narrow (<100 nm) base regions since the 1970 s with the introduction of advanced epitaxial technologies, such as molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD)7. However, several issues including inelastic electron scattering in the finite-width base region, finite base transit time, and quantum-mechanical reflections (e.g. impedance-mismatching) at the collector-base junction typically resulted in subpar current gains at or below room temperature2,4,5. In addition, these epitaxial techniques add to the complexity in the time and cost of fabricating such structures.

The advent of 2D van der Waals materials6, such as graphene7 and the transition metal dichalcogenides8,9,10,11,12,13 (TMDs), has sparked a paradigm shift in the design and engineering of atomic-scale systems. Their strong in-plane mechanical stability in addition to their weak out-of-plane van der Waals forces allow us to amalgamate atomic-scale heterostructures11 exhibiting novel optoelectronic phenomena14,15 and functionalities16,17,18,19. Recently, ballistic hot electron transistors incorporating either monolayer graphene or monolayer MoS2 in the base region have achieved high current modulation20,21 (ION/IOFF ~ 104–105) and high-current gain22 (α ~ 0.95) at room temperature, respectively. This unique class of 2D material-base hot electron transistors (2D-HETs) shows great potential for 2D material-based high-frequency logic applications upon further device optimization16,23,24,25,26.

The 2D-HETs rely upon the vertical (e.g. out-of-plane) emission of hot electrons through an atomic-scale base region and the subsequent filtering of these hot electrons by a built-in potential energy barrier near the base-collector junction. However, in spite of these accomplishments, there is a dearth of insight into the actual out-of-plane transport (e.g. the dominant scattering mechanisms and the actual potential energy landscape) experienced by the hot electrons in these 2D-HETs27,28,29. As far as we know, all previous 2D-HETs operated under the application of a positive collector-base potential (VCB > 0) and thus were limited to a single functionality, namely the typical unipolar hot electron transistor behavior20,21. To augment the functionality of electronics such as multi-level cells for low footprint vertical transport-based memory applications, here we introduce an alternative and peculiar conduction mode of operation which we refer to as a dual-mode operation in our 2D-HETs upon application of either a positive collector-base potential (VCB > 0) or a negative collector-base potential (VCB < 0). Thus, our 2D-HETs can operate in either a hot-electron or a reverse-current dominating mode depending upon the particular bias configuration. The 2D-HETs operate at room temperature and their current gains can be dynamically tuned by varying VCB. Furthermore, we surmise that the current saturation-like behavior in the transfer characteristics of the MoS2-HETs when operated in the reverse-current dominating mode (VCB < 0) could serve as a multi-level cell (e.g. data storage) in future multi-functional 2D material-based high-density and low-energy hot-carrier electronic (e.g. vertical transport based logic and memory) applications.

Results

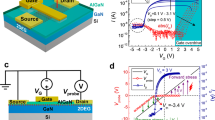

We demonstrate vertical transport 2D-HETs which exhibit a novel dual-mode operation by incorporating either monolayer MoS2 (MoS2-HET) or monolayer graphene (G-HET) in the base region. The device structure of the 2D-HET is presented in Fig. 1a and a top-view optical micrograph of an actual MoS2-HET is shown in Fig. 1b. The three-terminal device consists of a degenerately-doped n++ silicon substrate (ND ~ 1019 cm−3) as the emitter (E), a monolayer of chemical vapor deposition (CVD) grown 2D material (e.g. either MoS2 or graphene) as the base (B), and sputtered (~45 nm) ITO as the collector (C). A thermally grown thin (~3 nm) SiO2 tunnel barrier separates the emitter and base terminals, whereas an atomic-layer deposited (~55 nm) HfO2 separates the base and collector and serves as the filtering barrier. The detailed fabrication process is described in the Methods and in our previous work22. In this particular study, a common-base configuration was employed during the electrical measurements. Note that both of the base contacts are grounded during the electrical measurements in order to achieve a uniform potential distribution across the MoS2 base region.

(a) An isometric view of an MoS2-HET device structure. The capital letters E, B, and C represent the emitter, base, and collector, respectively. (b) Optical micrograph (top-view) of an actual MoS2-HET device. The scale bar is 100 μm. The dashed circle outlines the MoS2 region. (c) Energy band diagram depicting the collector current contributions at the on-state condition for two different polarities of the collector-base voltage. For VCB > 0 (dashed red lines), the hot-electrons tunneling through the emitter-base tunnel barrier have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome the filter barrier and reach the collector, whereas for VCB < 0 (dotted blue lines), electrons flow from the ITO to the base region to form a reverse base-collector current. (d) Common-base output characteristics. The collector current is shown as a function of VCB at VBE = 0 V, +1 V, +2 V, and +3 V.

We first focus on describing the two modes of operation for the 2D-HETs using energy band diagrams in order to clearly understand the physics governing the device transport. The 2D-HET with monolayer MoS2 as the base (MoS2-HET) will serve as an example. Figure 1c shows the energy band diagram for the off-state and the on-state conditions of the MoS2-HETs. In the absence of an applied VCB, most of the hot-electrons injected through the tunnel oxide have insufficient kinetic energy to overcome the filter barrier at the collector-base junction and do not reach the collector. Instead, they back-scatter and thermalize into the MoS2 base region. However, the situation drastically changes with the application of a large VCB. There are two possible cases for the on-state condition of the MoS2-HETs, depending upon the polarity of the applied VCB. The first case describes the typical hot-electron injection behavior and occurs for VCB > 0. In this scenario, hot-electrons tunneling through the emitter-base tunnel oxide have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome the filter barrier, reach the collector, and contribute to the collector current (IC). The second case describes a reverse-current behavior, which is a novel feature and mode of operation enabled by our 2D-HETs, and occurs for VCB < 0. In this scenario, the injected hot-electrons tunneling from the emitter do not have sufficient kinetic energy to surpass the raised filter barrier. Subsequently, these electrons are back-scattered and accumulate within the 2D material-base region which serves to suppress the base-collector reverse-current (IC). Interestingly, ΔIC, which denotes the amount of change in the base-collector current due to the hot electron injection from the emitter, can be tuned with the applied VBE in this mode of operation. Figure 1d shows the common-base output characteristics of one of our MoS2-HETs. The collector current (IC) is shown as a function of VCB at various VBE. It is evident that IC increases at a large positive VCB whereas IC is suppressed at a large negative VCB. Thus, by adjusting the polarity of VCB, it is possible to operate the 2D-HETs such that their collector current is mainly contributed by either hot-electrons originating from the emitter or electrons originating from the collector. Since ΔIC is the change in the collector current caused by the injection of the hot electron input current (e.g. an increasing magnitude of VBE > 0 modulates ΔIC), it will be used instead of IC for the discussion of the dual-mode operation for the remainder of this report.

Hot-electron dominating mode of operation in the MoS2-HETs

We first characterize the MoS2-HET in the hot-electron dominating mode of operation by applying positive VCB. Figure 2a shows the energy band diagram depicting the conduction and valence band edges at the collector-base junction with a positive VCB applied. In this mode of operation, once hot-electrons tunneling through the emitter-base tunnel barrier have sufficient kinetic energy, they can vertically transport through the MoS2 base region, surpass the filter barrier at the collector-base junction, and reach the collector. Consequently, an increasingly positive VCB will continue to effectively make the filter potential barrier thinner and promote hot-electrons reaching the collector due to an increase in their transmission probability. This qualitative behavior is exhibited in the input and transfer characteristics of the MoS2-HETs. The input characteristics (IE-VBE) correspond to how the emitter current depends on VBE, whereas the transfer characteristics (IC-VBE) correspond to the manner in which the collector current varies with VBE. Figure 2b shows the input and transfer characteristics for one of MoS2-HETs. The emitter current (IE) and the collector current (IC) are shown as a function of VBE (VBE was swept from 0 to +3 V) at a VCB of +2 V. Both currents rapidly increase at larger VBE, as is typical for HETs. From the input and transfer characteristics, the common-base current gain (α) of this device can be determined, which is a figure of merit for HETs and is defined as α = IC/IE. For this particular device and biasing condition of VCB = +2 V and VBE = +3 V, α is about 0.81, which implies that at least 80% of the injected hot-electrons ballistically traverse the single-layer MoS2 base region at room temperature. Further details concerning the hot-electron dominating mode of operation in the MoS2-HETs is mentioned in our previous work22.

(a) Energy band diagram depicting the MoS2-HETs operating in the hot-electron dominating mode. The conduction and valence band edges at the collector-base junction are shown for a positive VCB, which reduces the filter barrier for the hot-electrons. (b) Input and transfer characteristics for an MoS2-HET. The emitter current (black squares) and the collector current (red circles) are shown as a function of VBE at VCB = +2 V.

Reverse-current mode of operation in the MoS2-HETs

Shifting from the hot-electron dominating mode of the MoS2-HET, we next investigate the device characteristics operating under the reverse-current dominating condition. Figure 3a shows the energy band diagram depicting the reverse-current mode of operation for the MoS2-HET. Specifically, Fig. 3a shows the conduction and valence band edges at the collector-base junction with a negative VCB applied. In this mode of operation, the increasingly negative VCB drives more and more electrons to flow from the degenerately n-doped ITO conduction band, past the filter barrier and into the base region, thus forming the reverse-current. With the injection of hot-electrons from the emitter, the continuously increasing filter barrier (VCB < 0) causes these hot-electrons to have insufficient kinetic energy to reach the collector and thus they back-scatter into the MoS2 base region. Consequently, these back-scattered electrons build up in the MoS2 base region which cause a deficiency in the available density of states in the MoS2 and thereby decrease or suppress the reverse-current flowing into the base region from the degenerately n-doped ITO conduction band. The change or modulation in the reverse base-collector current (IC) caused by the injected hot-electrons from the emitter into the MoS2 base region is denoted as ΔIC. This reverse base-collector current (ΔIC) can be modulated with VBE by tuning the amount of hot-electrons that are injected from the emitter and which eventually build up in the MoS2 base region. In the reverse-current mode of operation (VCB < 0), we define the effective current gain: α* = |ΔIC|/|IE| as the ratio of the measured reverse base-collector current to the injected hot-electron emitter current in the MoS2 base region, where ΔIC is defined as the suppressed reverse base-collector current arising from the build-up of the injected hot-electrons in the MoS2 base region. Thus, our MoS2-HETs, when biased in the reverse-current dominating mode, enable the dynamic control of the available density of states in the 2D base region by varying VBE. This qualitative behavior for the reverse base-collector current mode of operation is exhibited in the input and transfer characteristics of the MoS2-HETs. Figure 3b shows the input and transfer characteristics for one of the MoS2-HETs biased at three different VCB (VCB = 0, −8, and −10 V). It is evident that both the emitter and collector currents increase with larger negative VCB. Similarly, Fig. 3c shows a family of transfer characteristics, with the suppressed reverse base-collector current (ΔIC) as a function of VBE shown for various negative VCB. The transfer characteristics of the MoS2-HET when operated in the reverse-current mode (VCB < 0) are peculiar in that the reverse base-collector current tends to saturate with increasing VBE. Additionally, the reverse-current magnitude increases with larger negative VCB bias. We speculate that this novel current saturation-like behavior could serve as a multi-level cell for low footprint vertical transport-based memory30,31,32,33,34,35applications in the future. As an example, consider biasing the 2D-HET at VBE = +3 V (e.g. the highest hot electron injection current to avoid dielectric breakdown of the tunnel barrier). We can vary the steady-state reverse-current (ΔIC) by setting VCB < 0 to various values. Based on Fig. 3c, we can address distinguishable (ΔIC) charge states for VCB from −6 V to −10 V and thus encode at least 4 states for a minimum of a 2-bit memory cell. Multi-level cells are memory units capable of storing more than one bit of information and thus can result in lower cost per unit of storage and higher data storage density. Furthermore, it was recently shown that cheaper multi-level cell flash drives used in practice are just as reliable as more expensive single-level cells36. Thus, our dual-mode 2D-HETs may find opportunities as ultra-dense multi-functional logic/memory units. From the input and transfer characteristics, we can next ascertain the effective current gain (α*) of this device for the reverse-current dominating mode of operation. Figure 3d shows α* for this MoS2-HET as a function of VBE at VCB = −10 V. Such a large negative VCB significantly raises the filter barrier height for the injected hot-electrons originating from the emitter, which causes them to back-scatter into the MoS2 base region and build up, leading to the effective suppression of the reverse base-collector current. Similar to the hot-electron dominating mode of operation in our previous paper22, it is evident that α* exhibits a nearly constant characteristic at all VBE with a value of at least 90% for this particular MoS2-HET biased at VCB = −10 V. The inset of Fig. 3d shows a family of α* characteristics as a function of VBE at several negative VCB (VCB = −4, −6, −8, −9, and −10 V). The effective current gain, α*, increases with negative VCB and exhibits a nearly constant characteristic throughout the entire VBE range with a magnitude of about 94% at VCB = −10 V.

(a) Energy band diagram depicting the MoS2-HETs operating in the reverse-current mode. Electrons flow from the degenerately n-doped ITO conduction band to the MoS2 base region upon application of a reverse-bias across the collector-base junction (VCB < 0). The conduction and valence band edges at the collector-base junction are shown for a negative VCB, which raises the filter barrier experienced by the hot-electrons tunneling from the emitter and subsequently promotes an electron build up in the base region. (b) Input and transfer characteristics for an MoS2-HET operating in the reverse-current mode. The emitter current (open symbols) and the collector current (filled symbols) are shown as a function of VBE at VCB = 0, −8 and −10 V. (c) Transfer characteristics for an MoS2-HET. The reverse base-collector current as a function of VBE is shown for VCB from 0 to −10 V with step of −1 V. (d) α* as a function of VBE at VCB = −10 V. The inset shows α* as a function of VBE at VCB = −4, −6, −8, −9, and −10 V.

Output characteristics and tunable current gain in the MoS2-HETs

With the analysis of the input and transfer characteristics complete, we now investigate the common-base output characteristics of the MoS2-HETs, which correspond to how the output collector current depends on VCB. In order to clearly present the dual-mode operation of our MoS2-HETs, the base-collector leakage current when VBE = 0 was subtracted from the measured collector current. Figure 4a shows the common-base output characteristics for one of the MoS2-HETs. The collector current is shown as a function of VCB at three positive VBE biases. The dual-mode operation is evident as the device is biased in either the hot-electron (VCB > 0) or the reverse-current (VCB < 0) dominating mode of operation. Above a critical electric field across the HfO2, the collector current is quite sensitive to modulation and rapidly increases with a further increase in VCB for both cases of VCB > 0 and VCB < 0. Based on Fig. 4a, the on-off current ratio (ION/IOFF) is about 140 when VCB = −10 V and VBE = +3 V, whereas ION/IOFF ~ 125 when VCB = +10 V and VBE = +3 V. In order to convey the robust and dual-mode operation of our MoS2-HETs, Fig. 4b shows a semi-log plot of the current gain as a function of VCB at positive VBE = +3 V, which is biased in both the hot-electron (α; VCB > 0) and the reverse-current (α*; VCB < 0) dominating modes of operation. The effective current gain, α*, increases with larger negative VCB as a result of a suppression in the reverse-current and reaches a very high-current gain with a value of about 90% at VCB = −9 V. It is evident that α* can be tuned around two orders of magnitude by varying VCB. A similar dependence of α on VCB for the hot-electron dominating case exists as shown in the right portion of Fig. 4b. In the hot-electron dominating mode of operation (VCB > 0), α increases with an increasingly positive VCB and can be tuned over an order of magnitude since this lowers the filter potential barrier experienced by the hot-electrons and allows them to reach the collector.

Output characteristics and tunable current gain in the graphene-HETs

Furthermore, in order to demonstrate the novel dual-mode operation enabled by our 2D material-base hot electron transistors, we shall now investigate our G-HETs. Figure 5a shows the common-base output characteristics in one of our G-HETs, which is biased in both modes of operation. The collector current is shown as a function of VCB at two positive VBE biases. It is evident that a dual-mode operation is also observed in the G-HETs as the devices are biased in either the hot-electron (VCB > 0) or the reverse-current (VCB < 0) dominating modes of operation. Based on Fig. 5a, the on-off current ratio (ION/IOFF) is about 3 when VCB = −10 V and VBE = +2 V, whereas ION/IOFF ~ 2 when VCB = +10 V and VBE = +2 V. The current gain (α) increases with larger positive VCB as a result of a reduction of the filter barrier in the hot-electron dominating process, whereas the effective current gain (α*) increases with larger negative VCB due to suppression in the reverse base-collector current. Additionally, we observed that the current gain can be tuned by varying VCB as shown in Fig. 5b. Hence, by biasing either the MoS2-HETs or G-HETs in the common-base configurations, we have explicitly shown the existence of a dual-mode operation and a tunable current gain in our new class of 2D material-base hot electron transistors. Nevertheless, the profiles of both the collector current and the current gain in the output characteristics of the MoS2-HET and the G-HET are quite different. At this time, not much is known of the actual out-of-plane transport (e.g. the dominant scattering mechanisms and the actual potential energy landscape) experienced by the hot electrons in these 2D-HETs27,28,29. What we do know is that these are two very different materials (e.g. feature different conduction band offsets, etc.). Monolayer graphene lacks a bandgap and features a linear dispersion relation, whereas monolayer MoS2 has a direct bandgap and features a parabolic dispersion relation at the K and K’ points in the Brillouin zone. Furthermore, the effective mass of the electrons travelling perpendicular to the graphene was predicted to be ~ 25–30 mo in a seminal paper37. A few reasons for the particularly low current gain in the G-HET compared to the MoS2-HET, may be due to the fact that the graphene-HfO2 interface features a much higher filter barrier height (e.g. 2.05 eV) compared to that of the MoS2-HfO2 interface (e.g. 1.52 eV) as well as the possibility of more prevalent acoustic phonon scattering near the base-collector junction for graphene than for MoS2. Clearly, further investigations into the out-of-plane transport among different 2D materials and their contact with bulk dielectrics will greatly benefit future device optimization. In the mean time, further improvement in the device performance of the 2D-HETs will be directed towards increasing the injected tunneling current density to a more suitable level for practical applications. This can be achieved via fine tuning of the thickness, barrier height, and uniformity of the tunnel barrier, implementation of bilayer insulator tunnel barrier38, as well as lowering the contact resistance between the 2D material and the metallic contact leads (e.g. via chemical doping39 or 1D edge contact to 2D materials40).

Summary

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a novel vertical dual-mode 2D material-base hot-electron transistor (2D-HET) incorporating either monolayer MoS2 (MoS2-HET) or monolayer graphene (G-HET) in the base region. This new class of 2D-HETs can operate in either a hot-electron or a reverse-current dominating mode depending upon the particular bias configuration. For the hot-electron dominating mode of operation (VCB > 0), once the hot-electrons tunneling through the emitter-base tunnel barrier have sufficient kinetic energy, they can vertically transport through the 2D material base region, surpass the filter barrier at the collector-base junction, and reach the collector. For the reverse base-collector current dominating mode of operation (VCB < 0), the continuously increasing filter barrier precludes the injected hot-electrons from having sufficient kinetic energy to reach the collector, hence they back-scatter into the 2D material base region. Consequently, these back-scattered electrons build up in the 2D material base region, which induces a deficiency in the available density of states in the 2D material, thereby reducing the reverse base-collector current. Furthermore, these 2D-HETs operate at room temperature and their current gains can be dynamically tuned by varying VCB. This dual functionality is enabled by incorporating 2D materials in the base region of the HET structure and by varying the polarity of VCB. We anticipate our transistors will pave the way towards the realization of novel flexible 2D material-based high-density and low-energy hot-carrier electronic applications.

Methods

In this work, we commenced the fabrication process with a 100 mm degenerately-doped n++ (ND ~ 1 × 1019 cm−3) silicon wafer and performed a standard LOCal Oxidation of Silicon (LOCOS) procedure in order to define arrays of active areas for the 2D material-HETs, which were isolated from each other by a 300 nm thick SiO2 field oxide. With the silicon surface of the active areas exposed, we then thermally grew a thin ~3 nm SiO2 tunnel oxide. Afterwards, we transferred either a large-area CVD monolayer MoS2 or graphene on top of the substrate (e.g. SiO2 field oxide) so that the particular 2D material covered several arrays of active areas of the 2D material-HETs. The large-area monolayers of MoS2 and graphene were grown using CVD methods41,42 and transferred onto the substrates using PMMA transfer methods43,44. Subsequently, a photolithography step was performed to mask circular regions of the 2D material covering the active areas. The 2D material outside of the active regions was etched in order to isolate the various devices. The 2D material area of each device is about 8 × 104 μm2. A second photolithography step was performed in order to pattern and deposit the base contacts (20 nm thick Ti/100 nm thick Au for MoS2-HETs or 20 nm thick Cr/100 nm thick Au for G-HETs). A 1 nm thick Ti seed layer was evaporated on top of the 2D material and naturally oxidized in air, followed by atomic layer deposition (ALD) of a 55 nm thick HfO2 as the filtering barrier. A third photolithography step was performed in order to define a central circular top-gate (e.g. collector) region which encompasses the entire active area of the 2D material-HETs. We then RF sputtered 45 nm of ITO at room temperature into this circular region followed by lift-off. Finally, a fourth photolithography step was performed in order to pattern and deposit the side electrodes (150 nm thick Al/50 nm thick Au) on top of the filtering barrier dielectric. These metallic side electrodes intimately contact the central ITO collector region and allow for easy probing and biasing of the 2D material-HETs. Electrical measurements were performed with a Keithley 4200 Semiconductor Characterization System. All measurements were performed in air and at 300 K. The leakage current was subtracted for all of the data presented in the main text. Specifically, the base-collector leakage current when IE = 0 was subtracted from the measured collector current when biased in the common-base configuration.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lan, Y.-W. et al. Dual-mode operation of 2D material-base hot electron transistors. Sci. Rep. 6, 32503; doi: 10.1038/srep32503 (2016).

References

Mead, C. A. The Tunnel Emission Amplifier. Proc. IRE. 48, 359 (1960).

Heiblum, M. & Fischetti, M. V. Ballistic Hot-Electron Transistors. IBM J. Res. Dev. Vol. 34, No. 4, 530–549 (1990).

Hollis, M. A., Palmateer, S. C., Eastman, L. F., Dandekar, N. V. & Smith, P. M. Importance of Electron Scattering with Coupled Plasmon-Optical Phonon Modes in GaAs Planar Doped Barrier Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Letters. Vol. 4, Issue 12, 440–443 (1983).

Luryi, S. An Induced Base Hot-Electron Transistor. IEEE Electron Device Letters. Vol. 6, No. 4, 178–180 (1985).

Luryi, S. Induced Base Transistor. Physica 134B, 466–469 (1985).

Matthews, P. et al. Two-Dimensional Electron Gas Base Hot Electron Transistor. Electronics Letters. Vol. 26, No. 13, 862–864 (1990).

Sze, S. M. Introduction. In High-Speed Semiconductor Devices. (A Wiley-Interscience Publication, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, USA, 1990).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10451–10453 (2005).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Britnell, L. et al. Strong Light-Matter Interactions in Heterostructures of Atomically Thin Films. Science 340, 1311–1314 (2013).

Withers, F. et al. Light-emitting diodes by band-structure engineering in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 14, 301–306 (2015).

Mehr, W. et al. Vertical Graphene Base Transistor. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 33, 691–693 (2012).

Britnell, L. et al. Field-Effect Tunneling Transistor Based on Vertical Graphene Heterostructures. Science 335, 947–950 (2012).

Yang, H. et al. Graphene Barristor, a Triode Device with a Gate-Controlled Schottky Barrier. Science 336, 1140–1143 (2012).

Georgiou, T. et al. Vertical field-effect transistor based on graphene-WS2 heterostructures for flexible and transparent electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 100–103 (2013).

Vaziri, S. et al. A Graphene-Based Hot Electron Transistor. Nano Lett. 13, 1435–1439 (2013).

Zeng, C. et al. Vertical Graphene-Base Hot-Electron Transistor. Nano Lett. 13, 2370–2375 (2013).

Torres, C. M. Jr. et al. High-Current Gain Two-Dimensional MoS2-Base Hot-Electron Transistors. Nano Lett. 15, 7905–7912 (2015).

Kong, B. D., Zeng, C., Gaskill, D. K., Wang, K. L. & Kim, K. W. Two dimensional crystal tunneling devices for THz operation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 263112 (2012).

Di Lecce, V. et al. Graphene-Base Heterojunction Transistor: An Attractive Device for Terahertz Operation. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 60, 4263–4268 (2013).

Kong, B. D., Jin, Z. & Kim, K. W. Hot-Electron Transistors for Terahertz Operation Based on Two-Dimensional Crystal Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 054006 (2014).

Vaziri, S. et al. Going ballistic: Graphene hot electron transistors. Solid State Communications, ISSN 0038-1098, E-ISSN 1879–2766, 224, 64–75 (2015).

Zhang, Q., Fiori, G. & Iannaccone, G. On Transport in Vertical Graphene Heterostructures. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 35, 966–968 (2014).

Iannaccone, G., Zhang, Q., Bruzzone, S. & Fiori, G. Relevance of the physics of off-plane transport through 2D materials on the design of vertical transistors. In 2015 Joint International EUROSOI Workshop and International Conference on Ultimate Integration on Silicon (EUROSOI-ULIS) 89–92, doi: 10.1109/ULIS.2015.7063780 (2015).

Iannaccone, G., Zhang, Q., Bruzzone, S. & Fiori, G. Insights on the physics and application of off-plane quantum transport through graphene and 2D materials. Solid-State Electronics 115, 213–218 (2016).

Hong, A. et al. Graphene Flash Memory. ACS Nano. Vol. 5, No. 10, 7812–7817 (2011).

Lee, S. et al. Impact of Gate Work-Function on Memory Characteristics in Al2O3/HfOx/Al2O3/Graphene Charge-Trap Memory Devices. Applied Physics Letters. 100, 023109 (2012).

Song, E. B. et al. Robust Bi-Stable Memory Operation in Single-Layer Graphene Ferroelectric Memory. Applied Physics Letters. 99, 042109 (2011).

Zhang, E. et al. Tunable Charge-Trap Memory Based on Few-Layer MoS2 . ACS Nano. Vol. 9, No. 1, 612–619 (2015).

Bertolazzi, S., Krasnozhon, D. & Kis, A. Nonvolatile Memory Cells Based on MoS2/Graphene Heterostructures. ACS Nano. Vol. 7, No. 4, 3246–3252 (2013).

Choi, M. S. et al. Controlled Charge Trapping by Molybdenum Disulphide and Graphene in Ultrathin Heterostructured Memory Devices. Nature Communications. 4, 1624 (2013).

Schroeder, B., Lagisetty, R. & Merchant, A. Flash Reliability in Production: The Expected and the Unexpected. In 14th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST’16). Santa Clara, CA: USENIX Association, pp. 67–80, Feb. 2016.

Wallace, P. R. The Band Theory of Graphite. Physical Review. 71(9), 622–634 (1947).

Vaziri, S. et al. Bilayer Insulator Tunnel Barriers for Graphene-Based Vertical Hot-Electron Transistors. Nanoscale. 7, 13096–13104 (2015).

Kappera, R. et al. Phase-Engineered Low-Resistance Contacts for Ultrathin MoS2 Transistors. Nature Materials. 13, 1128–1134 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. One-Dimensional Electrical Contact to a Two-Dimensional Material. Science. 342(6158), 614–617 (2013).

Lee, Y.-H. et al. Synthesis and Transfer of Single-Layer Transition Metal Disulfides on Diverse Surfaces. Nano Lett. 13, 1852–1857 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Large-Area Synthesis of High-Quality and Uniform Graphene Films on Copper Foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Nguyen, L.-N. et al. Resonant Tunneling through Discrete Quantum States in Stacked Atomic-Layered MoS2 . Nano Lett. 14, 2381–2386 (2014).

Gao, L. et al. Repeated growth and bubbling transfer of graphene with millimetre-size single-crystal grains using platinum. Nat. Commun. 3, 699 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the collaboration of this research with King Abdul-Aziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) via The Center of Excellence for Green Nanotechnologies (CEGN). This work was in part supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Award # NSF-EFRI-1433541. C. M. T. Jr. thanks the Department of Defense SMART (Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation) Scholarship for graduate scholarship funding. This research was funded in part by the National Science Council of Taiwan under contract No. NSC 103-2917-I-564-017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L.W., Y.-W.L. and C.M.T. Jr. conceived the idea and designed the experiments; J.R.A. and M.B.L. provided the CVD graphene; Y.S. and L.-J.L. provided the MoS2 samples; C.M.T. Jr., X.Z. and S.-H.T. fabricated the devices; Y.-W.L. and C.M.T. Jr. performed the electrical measurements; Y.-W.L., C.M.T. Jr., X.Z., W.-K.Y., H.Q. and K.L.W. analyzed the data. All of the authors discussed the results and wrote the paper together.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, YW., Torres, Jr., C., Zhu, X. et al. Dual-mode operation of 2D material-base hot electron transistors. Sci Rep 6, 32503 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32503

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32503

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.