Abstract

Recent technical advances have greatly facilitated G-protein coupled receptors crystallography as evidenced by the number of successful x-ray structures that have been reported recently. These technical advances include novel detergents, specialised crystallography techniques as well as protein engineering solutions such as fusions and conformational thermostabilisation. Using conformational thermostabilisation, it is possible to generate variants of GPCRs that exhibit significantly increased stability in detergent micelles whilst preferentially occupying a single conformation. In this paper we describe for the first time the application of this technique to a member of a class B GPCR, the corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R). Mutational screening in the presence of the inverse agonist, CP-376395, resulted in the identification of a construct with twelve point mutations that exhibited significantly increased thermal stability in a range of detergents. We further describe the subsequent construct engineering steps that eventually yielded a crystallisation-ready construct which recently led to the solution of the first x-ray structure of a class B receptor. Finally, we have used molecular dynamic simulation to provide structural insight into CRF1R instability as well as the stabilising effects of the mutants, which may be extended to other class B receptors considering the high degree of structural conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the largest superfamilies of transmembrane receptors, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) have long been targets for drug discovery due to their importance in signalling cascades throughout the body. This diverse family can recognise a wide variety of ligands ranging from small molecule neurotransmitters1,2 and metabolites3 to large peptide hormones4,5 and chemokines6. The complexity of GPCR function is compounded by their capacity to activate a multiplicity of downstream pathways, whether this be mediated through trimeric G-proteins (of which there are at least 17 different mammalian genes encoding Gα subtypes, 5 types of Gβ and 12 types of Gγ)7, arrestins8, or other mediators9. GPCRs can be divided into 4 major families according to sequence homology and functional similarity10. The majority of structural analysis has focussed on Class A receptors (rhodopsin-like) which make up the predominant class of GPCRs in the body11,12, however recent successes have provided structural examples from other families: Class B (secretin)13,14, Class C (metabotropic glutamate)15,16 and Class F (frizzled/smoothened)17.

The corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R) is a member of the Class B, or secretin receptor family4,18. It is predominantly expressed in the pituitary and areas of the central nervous system, such as hypothalamus, amygdala and cortex and plays a key role in the regulation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal stress axis in mammals19,20,21. Thus, antagonists of the receptor have been investigated as possible therapeutic agents to combat stress-related disorders like anxiety and depression22,23. Its natural ligand, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), is a 41 amino acid peptide hormone that interacts with the receptor through both the 7 transmembrane helical bundle and a large amino-terminal extracellular domain (ECD); a characteristic of Class B GPCRs24. As with other members of its Class, the carboxy-terminus of the peptide ligand binds to the ECD of the receptor and the amino-terminus of the peptide interacts with the transmembrane domain (TMD). Structures of the ECD of CRF1R have been solved in complex with peptide ligands25,26; however, only recently the structure of the TMD of CRF1R was determined, bound with an inverse agonist, CP-37639513.

GPCRs are highly dynamic proteins and inherently unstable when removed from the lipidic environment of the membrane. This makes them challenging targets for structural studies. Stability and homogeneity are recognised traits that correlate with success in structural biology of membrane proteins27,28,29,30. These traits are in many ways linked. A level of homogeneity can be achieved through effective purification of the target protein, however monodispersity of the sample is in turn affected by its stability. This is especially relevant for membrane proteins where purification requires solubilisation in detergent micelles which are typically destabilising compared to the membrane31,32. Further heterogeneity can be present at a molecular level in the form of flexible regions such as loops, extended termini and mobile domains that can hinder crystallisation. These are typically removed or modified in the construct design of proteins that are difficult to crystallise33. Moreover, the dynamic nature of GPCRs and their ability to exist in a spectrum of conformations in the activation landscape creates additional diversity within the population34. We were able to overcome these difficulties and solve the structure of CRF1R by application of conformational thermostabilisation. This entailed the introduction of stabilising mutations throughout the receptor that locked the receptor into a single conformation, driven by the presence of the ligand. This stabilised receptor (StaR) generation process has been adopted successfully for a number of other GPCR targets, enabling high resolution structural analysis11,15,35,36,37.

In this paper we describe the generation of the CRF1R StaR through mutagenesis and the subsequent construct optimisation that enabled the receptor to be purified, crystallised and its structure solved to 3 Å resolution. The thermal stability of the StaR has been characterised, highlighting the link between stability and crystallisability and molecular dynamics simulation analyses point to a possible route of instability within the receptor as well as providing explanations for the stabilising effects of mutations.

Methods

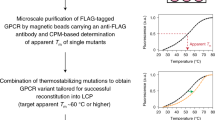

StaR generation

The CRF1R StaR was generated using a mutagenesis approach described previously36. Mutants were analysed for thermostability in the presence of the radioligand [3H]CP-376395. Stabilising mutations were combined to create a CRF1R StaR containing 12 mutations.

Cell culture

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were transfected using GeneJuice (Merck Millipore) according to manufacturer’s instructions and harvested after 48 hours using PBS supplemented with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche).

Thermostability measurement

Transiently transfected HEK293T cells were incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 × Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (PI) (Roche) with 30 nM [3H]CP-376395 and 120 nM cold CP-376395 (Tocris) for 18 hours at room temperature. All subsequent steps were performed at 4 °C. Cells were solubilized in either 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM) or 1% (w/v) n-decyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DM) for 1 hour and crude lysates cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes. Lysates were incubated with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), pre-equilibrated with sample buffer, for 1 hr 30 min before washing with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, supplemented with either 0.03% (w/v) DDM or 0.15% (w/v) DM. For detergent exchange experiments, DM solubilised samples were exchanged with wash buffer substituted with either 0.4% (w/v) n-nonyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (NM), 0.3% (w/v) n-nonyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (NG), 0.8% (w/v) n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (OG), 0.4% (w/v) n-octyl-β-d-thioglucopyranoside (OTG), 0.35% (w/v) decanoyl-N-hydroxyethylglucamide (HEGA10), 0.35% (w/v) tetraethylene glycol monoctyl ether (C8E4), or 0.1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-n,n-dimethylamine-n-oxide (LDAO). Receptor was eluted from the resin using wash buffer containing 100 mM histidine, 30 nM [3H]CP-376395 and 120 nM cold CP-376395 and incubated at 4 °C for 1 hour. A2AR StaR samples were treated as above but using buffers containing 400 mM NaCl. These samples were eluted from the Ni-NTA resin using wash buffer containing 100 mM histidine and 100 nM [3H] ZM241385.

For buffer and additive screening experiments, the receptor was eluted from Ni-NTA resin using wash buffer containing 100 mM histidine. Histidine was removed and the buffer exchanged by passing the material through a PD-10 desalting column. Receptor was eluted in either 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2x PI, 0.15% (w/v) DM, pH 7.5 (for buffer exchange experiments) or 100 mM sodium citrate, 150 mM NaCl, 2x PI, 0.15% DM, pH 5.5 (for additive screen experiments) and incubated with 30 nM [3H]CP-376395 and 120 nM cold CP-376395 overnight. This material was then mixed in a 1:1 ratio with exchange buffer (200 mM buffer, 150 mM NaCl, 0.15% DM) or additive buffer (100 mM sodium citrate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.15% DM, 400 mM additive, pH5.5) and incubated at 4 °C for 5 min. Buffers were chosen based upon optimum buffering capacity at the given pH.

Thermostability of the receptor was measured by incubation at varying temperatures for 30 minutes followed by separation of unbound radioligand by gel filtration as described previously38. Levels of ligand-bound receptor were determined using a liquid scintillation counter. A thermal stability measurement (Tm) was defined as the temperature at which 50% ligand binding was retained after a 30 min heat step at that temperature. Tm curves were analysed by GraphPad Prism v5.01 using sigmoidal dose response curve fitting.

Half-life measurement

Samples were treated as above, except in place of the 30 minute heating step, samples were incubated at 4 °C or 10 °C for specified periods of time before separation of unbound radioligand by gel filtration. Half-life curves were analysed by GraphPad Prism v5.01 using one phase exponential decay curve fitting.

Truncation and T4-lysozyme fusion constructs

A panel of N- and C-terminal truncation variants of CRF1R was designed based on secondary structure prediction (HHpred server39) and hydropathy plots40. Truncated receptors were expressed in HEK293T cells as C-terminal fusions with eGFP41. Receptors were solubilized in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 2% (w/v) DM and their expression levels and stability was assayed by fluorescence-detection size exclusion chromatography (FSEC) as described previously42, in running buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.15% (w/v) DM. In parallel, a panel of T4 lysozyme insertions into the predicted locations of ICL2 or ICL3 were analysed in a similar fashion.

Pharmacology

For saturation binding experiments, membranes were prepared from HEK293T cells transiently expressing wild-type CRF1R, CRF1R StaR, CRF1R StaR with T4L fusion, or CRF1R-#105 as described36 and incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) polyethylinimine (PEI) with [3H]CP-376395 (0–60 nM) in the presence or absence of 30 μM cold CP-376395. Final DMSO concentration in each reaction was 5% (v/v). Membranes were incubated for 18 hours at room temperature prior to rapid filtration through 96-well GF/C UniFilter plates pre-soaked in 0.3% (w/v) PEI, followed by washing with PBS containing 0.15% (w/v) CHAPS. Plates were dried, 50 μl Ultima Gold-F scintillation fluid added per well and bound ligand measured using a Packard Microbeta counter. To obtain Kd, data were analysed using a global fitted one-site binding hyperbola in GraphPad Prism v5. Heterologous competition analysis was conducted as above, incubating each construct with Kd concentrations of radioligand and a dilution series of competing ligand. To obtain Ki, data were analysed using a globally fitted one-site fit Ki analysis in GraphPad Prism v5.01.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The three dimensional coordinates of CRF1R in complex with the small molecule antagonist CP-37639513 have been downloaded from the Protein Data Bank43 (PDB ID: 4K5Y). The receptor has been prepared with the Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro (Schrödinger Release 2014-2: Maestro, version 9.8, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014); only the protein and the ligand in chain C have been included and His1552.50 (Wootten numbering in superscript) has been considered to be protonated. Hydrogen atoms have been energy minimized using the OPLS2.1 force field. The conformation of missing loop residues have been predicted using Prime (Version 3.6, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014). The WT molecular model was created in Maestro by changing the StaR mutations to the corresponding WT residues. For these residues the side chain rotamers have been manually selected and energy minimized in Prime.

OG molecules have been prepared in Maestro and parameterized using the OPLS2.1 force field. To test the detergent behavior, a system composed by 256 OG molecules randomly located in an orthorhombic water cell including 22740 solvent molecules was created using the System Builder (Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, version 3.8, D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2014 and Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools, version 3.8, Schrödinger, New York, NY, 2014). The system was equilibrated using the default Desmond Relax protocol in Maestro. The final state has been subjected to 50 ns MD using DesmondGPU at 300 K/1atm in the NPT ensemble using a Nose-Hoover thermostat and a Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat44 with a 2.0 ps relaxation time. Coulomb interactions were evaluated using a 9 Å short range cutoff and smooth particle mesh Ewald as long range method (Ewald tolerance = 10−9). During the simulation the OG molecules quickly formed a self-assembled aggregate micelle structure as expected.

A total of 224 OG molecules were manually placed using Maestro around the hydrophobic region of the CRF1R StaR helical bundle oriented with the polar heads toward the solvent and the hydrophobic tails toward the receptor. The system was included in an orthorhombic water cell box including 12670 water molecules and neutralized by 46 Cl- and 38 Na+ (corresponding to 0.15 M salt concentration) using the System Builder in Maestro. After the Desmond Relax protocol in Maestro the micelle was equilibrated for 10 ns keeping the protein and ligand non-hydrogen atoms restrained using the same MD protocol described above. The WT CRF1R system was generated taking the obtained equilibrated OG-CRF1R StaR system and replacing the protein with the WT receptor model in Maestro. The total charge of the new system was neutralised removing a sodium ion and relaxed with the Desmond Relax protocol in Maestro. For both WT and StaR systems three independent 100 ns MD simulation were carried out with the same MD settings described above at a temperature of 283 K and without restrains on heavy atoms.

Results

StaR generation

Wild type CRF1R is highly unstable when solubilised from the lipid bilayer in detergents, precluding its use in structural studies. We have generated a conformationally stabilised CRF1R through mutagenesis and thermostability profiling in the presence of the inverse agonist CP-376395. Residues 114–415 of CRF1R were one by one mutated to alanine and transiently expressed in mammalian HEK293T cells. Where an alanine was present in the sequence to begin with, it was mutated to leucine. Detergent solubilised receptors were then analysed for thermal stability using radiolabelled [3H]CP-376395. A total number of 79 stabilising point mutations were identified, displaying an increase in Tm > 1 °C. The stabilising mutations were located throughout the receptor with the highest proportions found in TM1, TM2, TM5 and TM6. These mutations were combined to create a stabilised receptor containing 12 mutations; V120A1.40, L144A, W156A2.51, S160A2.55, S222L, K228A4.42, F260A, I277A5.44, Y309A6.35, F330A6.56, S349A7.43, Y363A7.57 (Wootten numbering in superscript) (Fig. 1). S222 was initially mutated to alanine, however subsequent mutation to leucine was found to be more favourable. This StaR shows a significantly enhanced stability compared to the wild type receptor, increasing the stability by 26 °C when solubilised in DDM. The StaR also shows a higher level of expression and a much improved FSEC profile (Fig. 1). While the wild type receptor largely aggregates into multimeric species, the StaR displays increased monodispersity eluting predominantly as a monomeric species. The StaR retains a shoulder to the main elution peak, however truncation of the receptor at both the N- and C-termini resolves the elution profile into a single, symmetrical peak, indicating that a proportion of instability may be driven by the N-terminal globular domain13.

Stabilising mutations present in the CRF1R StaR.

Panel (A) shows a ribbon diagram of the CRF1R StaR structure50 in complex with CP-376395 (sticks) (PDB ID: 4K5Y) coloured from TM1 in blue to TM7 in red. Positions of the stabilising mutations are highlighted in spheres and labelled with Wootten numbering in superscript. The StaR also contained the mutation S222L located in ICL2, not shown in the structure. Panel (B) compares the thermal stability of the CRF1R StaR (closed diamonds) to the wild-type receptor (open diamonds). Error bars are derived from standard deviations and calculated from duplicate temperature points within a single experiment. FSEC profiles of eGFP-tagged constructs analysed in DDM are shown in panel (C). Retention times of the void volume occurs at 5 min, monomeric full-length CRF1R at 8 min and free eGFP at ~10 min.

Stability profiling

Vapour diffusion crystallography of membrane proteins requires purification in an appropriate detergent to allow crystal contacts to form. Long-chained detergents such as DDM, while being sympathetic to protein stability, also have large micelles and can occlude the solvent exposed surface of membrane proteins. Receptor solubilised in DM was captured on Ni-NTA agarose resin and washed with a range of shorter-chained detergents to exchange the detergent associated with the receptor. Subsequent Tm analysis of these crudely purified samples revealed that the superior thermal stability of the StaR compared to wild type receptor was maintained across all the detergents tested (Table 1). The stability of wild type receptor is only measurable when solubilised in DDM, whereas the StaR shows an equivalent Tm in the significantly harsher conditions of OG (18 °C). The thermal stability of the CRF1R StaR was compared against the A2A StaR236, as a benchmark for successful crystallisation (Sup Figure 1). The CRF1R StaR showed an equal or higher stability than A2A StaR2 in all detergents tested except OG. A correlation between detergent chain length and stability is observed in both the final CRF1R StaR and a preliminary StaR containing only nine of the stabilising mutations (W156A2.51, S222L, K228A4.42, F260A, I277A5.44, Y309A6.35, F330A6.56, S349A7.43, Y363A7.57) with the lowest stability observed with the shorter-chained detergents. This is supported by time course activity measurements of both the preliminary and final StaR (Table 2, Sup Figure 2). Detergent exchanged receptor was incubated at either 4 °C or 10 °C and the activity of the receptor was determined at various time points. These temperatures were chosen due to their applicability to current protein crystallisation techniques. The preliminary StaR displayed an activity half-life of 10 days in DM when incubated at 4 °C, which dropped to 3.5 days when the temperature was raised to 10 °C. The final StaR showed a significantly longer half-life, increasing to 22 days at 4 °C in DM and almost 10 days when incubated at 10 °C. The half-life of the StaR reduced with shorter-chained detergents but the StaR was still 50% viable after 1.5 days at 4 °C in OTG. Taken together these data indicate that in contrast to the WT receptor, CRF1R StaR exhibits biochemical properties compatible with vapour diffusion crystallisation.

Construct optimisation for crystallisation

To aid the crystallisation of CRF1R the receptor was truncated at both the N- and C- termini. A matrix of truncation positions were created based upon secondary structure prediction and hydropathy plots and screened for expression and thermal stability by FSEC. The N-terminal truncations focussing around the junction between the N-terminal globular domain and the proposed start of TM1 appeared to be quite sensitive (Fig. 2). Expression levels suffered for all N-terminal truncations, however a compromise of truncation stringency and expression was reached with NΔ103 whilst retaining a monodisperse elution profile. C-terminal truncations using this background had less of an impact on expression levels, however the FSEC elution profiles were improved. The optimal truncation position NΔ103/CΔ42 removed both the N-terminal globular domain and the predicted C-terminal helix 8. Truncation of the receptor had no observable effect on CP-376395 ligand affinity (Sup. Figure 3) but significantly improved the FSEC profile into a single, symmetrical peak.

FSEC analysis of CRF1R StaR truncated constructs.

Traces are shown representing a matrix of N-terminal truncations (panel (A)), C-terminal truncations based upon an N-terminal Δ103 construct (panel (B)) and the final truncated construct compared to the full length receptor (panel (C)). All constructs were analysed in the absence of ligand. Retention time of the void volume occurs at 16 min and free eGFP at ~32 min.

To aid in crystallisation of the receptor in lipidic cubic phase, T4 lysozyme was inserted into ICL2 between residues T220 and D224 (construct CRF1R-#10513). The fusion caused a decrease in stability by ~7 °C, however the pharmacology of this construct remained unchanged compared to the wild type receptor (Sup. Figure 3, sup. Table 1) and generated high resolution diffracting crystals13.

Buffer optimisation

The final crystallisation construct was analysed for thermal stability in a range of different buffers and additives to identify stabilising conditions for purification and crystallisation. Initial screens suggested that CRF1R-#105 material showed a higher stability at lower pH (5.5-7) (Fig. 3). As different buffering salts were used based upon their optimum buffering capacities, the stability of the receptor may have been influenced by the specific buffer used. Indeed, two buffers stood out; sodium citrate and Bicine pH9 gave significantly higher radioligand binding than the others tested. Fine tuning of the buffer pH revealed sodium citrate at pH5.5 to be the most stabilising. A number of additives were then screened for further improvements in stability, comprising both monovalent and divalent salts (Table 3). Divalent cations were generally destabilising, although this could be a result of the chelating properties of the divalent anion of citric acid, which at pH5.5 would form a large proportion of the ionic distribution (approx. 40%). Lithium citrate proved to be the most stabilising additive, increasing both the Bmax and Tm (Table 3).

CRF1R molecular dynamics simulation

To better understand the difference in thermostability between the CRF1R StaR and the WT receptor we analysed their conformational changes occurring after 100 ns MD at 10 °C in the harsh detergent OG (Sup. Figure 4, E). In these conditions CRF1R StaR is stable, whilst the WT receptor quickly unfolds (Table 1). In both systems the detergent molecules create a stable micelle around the hydrophobic regions of the TM domain. However, the helical bundle shows a difference in macroscopic behaviour between the StaR and the WT receptor (Figs 4A,B). In the first case, the crystallographic conformation is very stable, while the three independent WT simulations show the initial signs of instability and unfolding even in this relative short time frame. In this system the initial steps of the receptor unfolding are variable, but generally involve TM4, TM5, TM6 and TM7 (Table 4). The increase in the TM stability of the StaR compared to that of WT during the simulations appeared variable and not linked to the number of mutations in the helices. This supports the conclusion that the effect of the StaR mutations on the conformational rigidity is complex and relates to the whole helical bundle, not just a single TM in isolation. Particularly remarkable was the difference in TM5, TM6 and TM7 conformational stability between WT and the StaR. During the WT MD simulations the presence of isoleucine at position 2775.44 (mutated to Ala in the StaR receptor) can promote the insertion of OG molecules between TM5 and TM6 close to the CP-376395 binding site (Figs 4C). In that region, TM6 shows a distorted conformation close to P3216.47 as a result of opposing forces acting at the extracellular and intracellular sides, in addition to the OG insertion. In the extracellular portion of the receptor we identified the hydrophobic collapse of F3306.56 on T3266.52 and L3517.45. The intracellular conformation of TM6 and TM7 are kept close to the helical bundle by interactions created by Y3096.35 and Y3637.57 with TM2 and TM3. Together these interactions cause a conformational strain, resulting in the bending of TM6 at position 6.47, followed by the insertion of the OG molecule. This instability is not detected in the StaR MD simulation probably as a consequence of the StaR mutations I277A5.44, Y309A6.35 and Y363A7.57.

CRF1R WT and StaR molecular dynamics analysis.

CRF1R structural superimposition of the starting and final conformation (after 100 ns explicit all-atom MD in an OG-water-micelle environment) for the StaR (panel (A)) and WT (panel (B)). Only the helical bundle backbone is shown as ribbon together with the ligand CP-376395. The initial conformation is coloured in green and magenta respectively for the StaR and the WT, while the final state is respectively in cyan and yellow. (panel (C)) Molecular destabilizing effects at the end of the CRF1R WT MD simulation (in yellow) of the residues I2775.44, Y3096.35, F3306.56 and Y3637.57 (all mutated to Ala in the StaR receptor). For clarity only TM5, TM6 and TM7 are shown. The backbone of the starting conformation is included in magenta as ribbon. I2775.44, F3306.56, T3266.52, L3517.45 and the ligand CP-376395 are shown as space filling, while Y3096.35, Y3637.57, P3216.47, S3497.43 and 2 OG molecules in stick representation.

The stabilising effect caused by mutations in the loops appears to be more complex and the length of the MD simulation is not long enough to allow reliable sampling of the high conformational space accessible to the highly flexible loops. However, the stabilisation could be linked to a change in loop entropy (see below).

Discussion

The stabilisation of CRF1R was pivotal in the elucidation of its crystal structure13. The WT receptor is unstable when solubilised in detergent and like all GPCRs exists in an equilibrium between a number of different conformations. The inability to purify a homogeneous preparation of WT CRF1R in detergent precludes it from high resolution structural studies. The process of StaR generation not only increases the stability of the receptor and its activity in a detergent environment, but because stabilisation is driven by the interaction of the receptor with a ligand, the resulting StaR is locked into a single conformation determined by the ligand used. The CRF1R StaR is 26 °C more stable than the wild type receptor in DDM and is locked into an inactive conformation by the small molecule inverse agonist ligand CP-376395. The affinity of CP-376395 is slightly increased at the full length StaR however the ligand binding properties of a range of small molecule antagonist ligands appear to be unchanged. Conversely, the affinity of the StaR for the peptide agonists CRF and sauvagine is severely compromised (data not shown). This is consistent with the arrangement of the helical bundle observed in the crystal structure of the CRF1R StaR which clearly showed the structure of the receptor to be in the inactive conformation.

There is a correlation between the propensity of a protein to crystallise and its stability45,28. Indeed this was highlighted by the stability profiling of the final construct. Buffer and additive screening identified sodium citrate pH5.5 and lithium citrate as stabilising conditions and interestingly the crystallisation conditions that yielded diffraction quality crystals comprised the same constituents13. However stability is not the only determinant of crystallisability. The final construct used in crystallisation was highly truncated, through removal of the N-terminal globular domain and predicted C-terminal helix 8 and modified by insertion of T4-lysozyme fusion into ICL2. These modifications aimed to reduce flexibility within the molecule and increases solvent exposed surface area to maximise the chances of crystallisation. Indeed, removal of the N-terminal globular domain provided a marked improvement in receptor monodispersity. This domain is a major component of agonist peptide ligand binding in CRF1R and its structure has been determined from refolded material expressed in E. coli26,25. The soluble domain of the homologue CRF2R has also been solved by NMR46,47 which reports a high level of dynamic flexibility within the molecule. Insertion of T4 lysozyme into ICL2 did not have a marked effect on the pharmacology of ligand binding but expression of the receptor was significantly reduced.

The mechanism by which the StaR mutations stabilise CRF1R in the inactive conformation is unclear. However MD simulations a posteriori comparing the CRF1R stabilised structure to a derived model of the wild-type receptor hint at possible routes of instability. The results of explicit-solvent all-atom MD analysis of CRF1R in a detergent micelle showed that the conformation of the helical bundle of the StaR receptor is more stable than the WT, in agreement with the experimental data. The simulations suggested that TM5 and TM6 are in particular stabilised by the StaR mutations F330A6.56, I277A5.44, Y309A6.35 and Y363A7.57. These mutations help to prevent the insertion of a detergent molecule between TM5 and TM6 close to the ligand binding site and the proline kink at position 6.47. The thermostabilising effect on the loops is harder to rationalise but it is possible that once the TM bundle has been rigidified, one way to absorb thermal energy without compromising structural integrity is to increase entropy where it can be afforded and conceptually, loops fall into that category given that they are generally flexible. Thermophile proteins have been shown to exhibit an entropic stabilisation characteristic compared to their mesophile homologues48. This could be achieved through two possible mechanisms reducing the difference in entropy between the folded and unfolded state: (I) increasing the flexibility of the loop in the folded state, implying an increased conformational entropy favourable to thermodynamic stability, or (II) decreasing the entropy of the unfolded state. In the unfolded state, glycine, without a β-carbon, is the residue with the highest conformational entropy. Proline, which can adopt only a few configurations and restricts the configurations allowed for the preceding residue, has the lowest conformational entropy49.

Conformational stabilisation is a powerful technique that is enabling for the structural determination of unstable GPCRs. GPCRs are dynamic proteins that convey signals across the cell membrane through structural rearrangement. The introduction of 12 point mutations in CRF1R allowed the stabilisation of the inactive conformation of the receptor whilst leaving the ligand binding pocket unchanged. Further construct optimisation to remove flexibility combined with detergent screening and buffer optimisation allowed the successful purification and ultimately structure determination of the first Class B GPCR.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kean, J. et al. Conformational thermostabilisation of corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1. Sci. Rep. 5, 11954; doi: 10.1038/srep11954 (2015).

References

Langmead, C. J. et al. Identification of novel adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonists by virtual screening. J. Med. Chem. 55, 1904–9 (2012).

Kruse, A. C. et al. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: novel opportunities for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 549–60 (2014).

Tonack, S., Tang, C. & Offermanns, S. Endogenous metabolites as ligands for G protein-coupled receptors modulating risk factors for metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304, H501–13 (2013).

Hollenstein, K. et al. Insights into the structure of class B GPCRs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 35, 12–22 (2014).

Parthier, C., Reedtz-Runge, S., Rudolph, R. & Stubbs, M. T. Passing the baton in class B GPCRs: peptide hormone activation via helix induction? Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 303–10 (2009).

Oppermann, M. Chemokine receptor CCR5: insights into structure, function and regulation. Cell. Signal. 16, 1201–10 (2004).

Wettschureck, N. & Offermanns, S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol. Rev. 85, 1159–204 (2005).

Luttrell, L. M. Arrestin pathways as drug targets. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 118, 469–97 (2013).

Sun, Y. et al. Dosage-dependent switch from G protein-coupled to G protein-independent signaling by a GPCR. EMBO J. 26, 53–64 (2007).

Fredriksson, R., Lagerström, M. C., Lundin, L.-G. & Schiöth, H. B. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups and fingerprints. Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 1256–72 (2003).

Doré, A. S. et al. Structure of the adenosine A(2A) receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure 19, 1283–93 (2011).

Katritch, V., Cherezov, V. & Stevens, R. C. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 53, 531–56 (2013).

Hollenstein, K. et al. Structure of class B GPCR corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1. Nature 499, 438–43 (2013).

Siu, F. Y. et al. Structure of the human glucagon class B G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 499, 444–9 (2013).

Doré, A. S. et al. Structure of class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain. Nature 511, 557–62 (2014).

Wu, H. et al. Structure of a class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 bound to an allosteric modulator. Science 344, 58–64 (2014).

Wang, C. et al. Structure of the human smoothened receptor bound to an antitumour agent. Nature 497, 338–43 (2013).

Perrin, M. H. & Vale, W. W. Corticotropin releasing factor receptors and their ligand family. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 885, 312–28 (1999).

Hemley, C. F., McCluskey, A. & Keller, P. A. Corticotropin releasing hormone--a GPCR drug target. Curr. Drug Targets 8, 105–15 (2007).

Bale, T. L. & Vale, W. W. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 525–57 (2004).

Naughton, M., Dinan, T. G. & Scott, L. V. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in psychiatric disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 124, 69–91 (2014).

Zhang, G. et al. Pharmacological characterization of a novel nonpeptide antagonist radioligand, (+/−)-N-[2-methyl-4-methoxyphenyl]-1-(1-(methoxymethyl) propyl)-6-methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-c]pyridin-4-amine ([3H]SN003) for corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305, 57–69 (2003).

Chen, Y. L. et al. 2-aryloxy-4-alkylaminopyridines: discovery of novel corticotropin-releasing factor 1 antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 51, 1385–92 (2008).

Couvineau, A. & Laburthe, M. The family B1 GPCR: structural aspects and interaction with accessory proteins. Curr. Drug Targets 13, 103–15 (2012).

Pioszak, A. A., Parker, N. R., Suino-Powell, K. & Xu, H. E. Molecular recognition of corticotropin-releasing factor by its G-protein-coupled receptor CRFR1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32900–12 (2008).

Grace, C. R. R. et al. NMR structure of the first extracellular domain of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (ECD1-CRF-R1) complexed with a high affinity agonist. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38580–9 (2010).

Kang, H. J., Lee, C. & Drew, D. Breaking the barriers in membrane protein crystallography. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 636–44 (2013).

Ericsson, U. B., Hallberg, B. M. & Detitta, G. T. Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. 357, 289–298 (2006).

Kean, J. et al. Characterization of a CorA Mg2+ transport channel from Methanococcus jannaschii using a Thermofluor-based stability assay. Mol. Membr. Biol. 25, 653–63 (2008).

Tate, C. G. A crystal clear solution for determining G-protein-coupled receptor structures. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 343–52 (2012).

Arachea, B. T. et al. Detergent selection for enhanced extraction of membrane proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 86, 12–20 (2012).

Seddon, A. M., Curnow, P. & Booth, P. J. Membrane proteins, lipids and detergents: not just a soap opera. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666, 105–17 (2004).

Derewenda, Z. S. The use of recombinant methods and molecular engineering in protein crystallization. Methods 34, 354–63 (2004).

Preininger, A. M., Meiler, J. & Hamm, H. E. Conformational flexibility and structural dynamics in GPCR-mediated G protein activation: a perspective. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2288–98 (2013).

Lebon, G., Bennett, K., Jazayeri, A. & Tate, C. G. Thermostabilisation of an agonist-bound conformation of the human adenosine A(2A) receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 409, 298–310 (2011).

Robertson, N. et al. The properties of thermostabilised G protein-coupled receptors (StaRs) and their use in drug discovery. Neuropharmacology 60, 36–44 (2011).

Miller-Gallacher, J. L. et al. The 2.1 Å resolution structure of cyanopindolol-bound β1-adrenoceptor identifies an intramembrane Na+ ion that stabilises the ligand-free receptor. PLoS One 9, e92727 (2014).

Shibata, Y. et al. Thermostabilization of the neurotensin receptor NTS1. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 262–77 (2009).

Söding, J., Biegert, A. & Lupas, A. N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W244–8 (2005).

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–80 (2001).

Cormack, B. P., Valdivia, R. H. & Falkow, S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173, 33–8 (1996).

Kawate, T. & Gouaux, E. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography for precrystallization screening of integral membrane proteins. Structure 14, 673–81 (2006).

Berman, H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–42 (2000).

Martyna, G. J., Tobias, D. J. & Klein, M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 4177 (1994).

Dupeux, F., Röwer, M., Seroul, G., Blot, D. & Márquez, J. A. A thermal stability assay can help to estimate the crystallization likelihood of biological samples. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 915–9 (2011).

Grace, C. R. R. et al. Structure of the N-terminal domain of a type B1 G protein-coupled receptor in complex with a peptide ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4858–63 (2007).

Grace, C. R. R. et al. NMR structure and peptide hormone binding site of the first extracellular domain of a type B1 G protein-coupled receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12836–41 (2004).

Meruelo, A. D., Han, S. K., Kim, S. & Bowie, J. U. Structural differences between thermophilic and mesophilic membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 21, 1746–53 (2012).

Sriprapundh, D., Vieille, C. & Zeikus, J. G. Molecular determinants of xylose isomerase thermal stability and activity: analysis of thermozymes by site-directed mutagenesis. Protein Eng. 13, 259–65 (2000).

Isberg, V. et al. GPCRDB: an information system for G protein-coupled receptors. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D422–5 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues at Heptares for their support and suggestions, especially G. Brown for sourcing the radio-labelled ligand. We also thank Chris Tate for advice on manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. carried out the receptor stabilisation, stability profiling, pharmacological analysis and additive screening. K.H. designed the final crystallography construct and carried out the fSEC analysis. A.B. carried out the M.D. simulation studies. A.J. contributed to receptor stabilisation and construct design. J.K., A.J., A.B. and F.H.M. wrote the manuscript. Project management was carried out by A.J. and F.H.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors are employees and shareholders of Heptares Therapeutics Ltd, a GPCR drug discovery company using structure-based drug design techniques

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kean, J., Bortolato, A., Hollenstein, K. et al. Conformational thermostabilisation of corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1. Sci Rep 5, 11954 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11954

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11954

This article is cited by

-

Yeast-based directed-evolution for high-throughput structural stabilization of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

An improved fluorescent tag and its nanobodies for membrane protein expression, stability assay, and purification

Communications Biology (2020)

-

Enabling STD-NMR fragment screening using stabilized native GPCR: A case study of adenosine receptor

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Opportunities for therapeutic antibodies directed at G-protein-coupled receptors

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2017)

-

Investigation of allosteric modulation mechanism of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 by molecular dynamics simulations, free energy and weak interaction analysis

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.