Abstract

Er3+ doped oxyfluoride tellurite glasses have been prepared. Three Judd-Ofelt parameters Ωt (t = 2, 4, 6) and radiative properties are calculated for prepared glasses. Emission characteristics are analyzed and it is found that prepared glasses possess larger calculated predicted spontaneous transition probability (39.97 s−1), emission cross section σem (10.18 × 10−21 cm2) and σem × Δλeff (945.32 × 10−28 cm3), corresponding to the 2.7 μm emission of Er3+: 4I11/2→ 4I13/2 transition. The results suggest that the prepared glasses might be appropriate optical material for mid-infrared laser application. Moreover, rate equation analysis which is rarely used in bulk glass has been carried out to explain the relationship between emission intensity and Er3+ concentration. The calculation results show that with the increment of Er3+ concentration, the energy transfer up-conversion rate of 4I13/2 state increases while the rate of 4I11/2 state reduces, resulting in the change of 2.7 μm emission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays a significant increment of interest has been shown in the Er3+ doped materials. Reasons could be explained that the 2.70 μm emission generated by Er3+: 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 transition has numerous applications in military weapons, remote sensing and laser surgery1,2. Moreover, transitions of 4I11/2 → 4I15/2 and 4I9/2 → 4I15/2 can be easily pumped by 980 nm and 808 nm commercial laser diode (LD), respectively. As is known, pumping at 980 nm directly into the upper 4I11/2 state results in the highest efficiency of 35%3. However, the existed excited-state absorption transition (ESA) of 4I11/2 → 4F7/2 that depletes the population in 4I11/2 state is unfavorable for 2.7 μm emission and must be avoided4. Experimentally, the best pump wavelength is near 792 nm because this wavelength is at the peak of cascade ESA transition of 4I13/2 → 2H11/2, which brings about a redistribution of population in 4I13/2 state and benefits the 2.7 μm emission5.

It is widely recognized that 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 transition of Er3+ is a self-terminating process, which means the upper 4I11/2 state has a short lifetime than the lower 4I13/2 state. Consequently, it requires some ways to deplete the lower state population and conserve upper state population for efficient 2.7 μm laser operation. Efficient approaches for population depletion consist of co-lasing of Er3+: 4I13/2 → 4I15/2 + 1.53 μm photon, energy transfer to sensitizing ions and energy transfer up-conversion: 4I13/2 + 4I13/ → 4I15/2 + 4I9/2 (ETU1) at high Er3+ concentration6. Moreover, the energy transfer up-conversion of 4I11/2 + 4I11/2 → 4F7/2 + 4I15/2 (ETU2) is harmful for conserve upper state population. The first two ways have been widely investigated according to various reports. However, as far as we known, few quantitative analysis of energy transfer up-conversion has been investigated in bulk glasses. By building proper equations, it is possible to quantitatively analyze energy transfer mechanism, which is one of major work we made in following paper.

In addition, host materials with low phonon energy that decreases the non-radiative relaxation rate are desirable for 2.7 μm laser operation. Therefore, it is crucially important to find a host material, which is suitable for both optical and physical requirement in order to obtain outstanding 2.7 μm laser properties. Recent reports have witnessed the development of various host glasses such as fluoride7, fluorophosphate8, germanate9 and chalcogenide10. The highest output power achieved in Er3+ doped fluoride glass fiber has been reported by S. Tokita in 2011. With the help of liquid-fluorocarbon that dissipates the heat, the output power reaches up to 24 W with slope efficiency of 14.5%. Since then, new progress of higher output in Er3+ doped fluoride glass fiber has hardly been reported. Except for fluoride glass, the mid-infrared laser output of these following glasses has not yet achieved up to now. The fluorophosphate glass, which combines the merits of fluoride glass and phosphate glass, does not show the good thermal stability and low phonon density as expected. Many efforts should still be made for practical use. The industrial development of germanate glass for mid-infrared laser is blocked by the drawbacks of high viscosity, high melting temperature and large amount of hydroxyl groups11. Although mid-infrared laser output of Pr3+ doped chalcogenide glass has been reported, due to its cost and fragility, significant efforts are still in the way to realize high output power in this kind of fiber laser for practical applications12,13.

As a conditional glass network former, tellurium dioxide (TeO2) has low phonon energy (~760 cm−1) and large refractive index, both of which are beneficial for high radiative index values. Moreover, the tellurite glasses show good thermal property and high doping concentration of rare earth ions without clustering, which make them a good luminescence material. However, the tellurite glass also has the problem of hydroxyl groups and tellurite glass fiber with low-loss is hard to be prepared due to the inhomogeneity of tellurite glass, which prevents them to be widely applied as mid-infrared material14. Oxyfluoride tellurite glasses (OFT), added with certain amount of fluoride, combine the advantages of oxide glasses with the good optical properties of fluorides. The addition of fluorides, on the one hand, could further decrease the phonon energy of glass matrix; on the other hand, it is an effective way to exhaust OH− content due to the reaction of OH− + F− → O2− + HF≠. The two main categories of OFT glasses are TeO2-ZnO-Na2O (TZN) based and TeO2-WO-La3O2 (TWL) based systems. The TWL system has very good thermal stability due to the existence of W-O banding in network. There is no obvious crystallization temperature (Tx) in some TWL glasses; therefore, it is quite beneficial for fiber drawing. However, the W-O banding located at 930 cm−1 in Raman spectra leads to high phonon energy15. The other challenge for TWL system is the difficulty of introducing F− ions into the glass matrix. Thus, the TWL system based OFT glass with large amount of fluoride has not reported yet. On the contrary, the TZN based system has quite low phonon energy (mainly due to the vibration of Te-O banding at 760 cm−1) and is easy to bring F ions in the glass matrix. The water-free OFT glass fiber based on TZN system has been achieved and shows good property16. However, the transmittance of it reaches around 80% and the glass transition temperature (Tg) of it is only 280 °C. Both the two factors are disadvantageous to high power and high optical performance laser material.

In this research, a kind of OFT glasses with molar compositions of 50TeO2 - 39RF2 (R = Ba, Mg, Zn) - 3NaF - 8 YF3 - xErF3 (x = 1, 3, 5, 7, 9) is reported. The large amount of TeO2 is the main glass network former and provides the main thermal and optical properties. The bivalent alkaline-earth ions were introduced into the matrix to enhance the emission of rare earth ions and play as the glass network modifier17,18. The introduction of large amount of F− ions decreases the phonon energy and depletes the OH−. The addition of YF3 into the matrix increases the viscosity of the melt and finally enhances the stability of the glass against crystallization19.Judd-Ofelt intensity parameters are determined to calculate the radiative transition probability and radiative lifetime of excited states. The 1.53 μm, 2.7 μm and 980 nm emissions under 808 nm excitation are investigated. Additionally, the rate equation analysis is used to calculate 4I13/2 state and 4I11/2 state energy transfer up-conversion rates as a quantitative explanation for energy transfer dynamics. In our previous work11,20, compositional dependence of energy transfer up-conversion rate has been investigated. In this work, we further investigate the Er3+ concentration dependence of energy transfer up-conversion rate, which sheds lights on elucidating of the concentration quenching mechanism and mid-infrared luminance behaviors for other investigators. The results reveal that incremental intensity of 2.7 μm emission is caused by the enhancement of ETU1 process and reduction of ETU2 process. Meanwhile, the concentration quenching of 2.7 μm emission happens due to the abrupt change of ETU2 process when reaching the saturation concentration.

Experimental

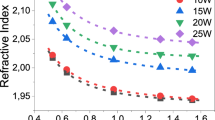

The 50 T glasses with molar compositions: 50TeO2 - 39RF2 (R = Ba, Mg, Zn) - 3NaF - 8 YF3 - xErF3 (x = 1, 3, 5, 7, 9) were prepared by mixing appropriate quantities of reagent grade raw materials and labeled as 50 T-1Er, 50 T-3Er, 50 T-5Er, 50 T-7Er, 50 T-9Er respectively. Then the 15 g mixture powder batches were melted at 900 °C for 20 min in corundum crucible under air atmosphere. The refined liquids were cast into a pre-heated stainless steel mould and then annealed for 120 min under glass transition temperature. Eventually, the samples were polished and cut to a 1 mm thickness pieces for test. The density indexes of the glasses were measured by the Archimedes method using distilled water as an immersion liquid. The refractive indexes were measured on MOPEL 2010/M Prism Coupler device (Metricon Co. America) at 632.8 nm, 1113 nm and 1539 nm. The thermal property was measured by differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) at the heating rate of 10 °C/min. The temperature of glass transition (Tg) was 425 °C. The FTIR transmittance spectra of the prepared samples were measured by Tensor 27 FTIR spectrophotometer (Brook Co. Germany). The absorption spectra were recorded by a UV3600 UV/VIS spectrophotometer in the range of 300–1600 nm with a resolution of 0.1 nm. Photoluminescence spectra in the ranges of 1400–1700 nm, 2550–2850 nm and 900–1050 nm were determined by a combined fluorescence lifetime and steady state spectrometer (FLSP920) (Edingburg Co. England), which was detected with a liquidnitrogen cooled PbS detector using an 808 nm LD as an excitation source. The fluorescence lifetimes of the 4I13/2 state, 4I11/2 state of Er3+ were measured with light pulse of the 808 nm LD and an HP 546800B 100-MHz oscilloscope. For the sake of obtaining comparable results, all the experimental conditions were consistently maintained and carried out at room temperature.

Results and discussion

Absorption and infrared transmittance properties

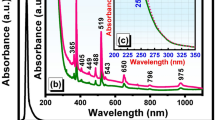

Figure 1 depicts the room temperature absorption spectrum and transmittance spectrum of 50 T glass doped with 7 mol% Er3+. It is easily found that in absorption spectrum the peak positions and shape of each transition of Er3+ in present sample are similar to those of other reported glasses21. Eleven bands of Er3+, centered at 1532 nm, 978 nm, 798 nm, 652 nm, 542 nm, 520 nm, 488 nm, 452 nm, 406 nm, 378 nm and 365 nm, correspond to the transitions originating from the 4I15/2 ground state to the excited levels 4I13/2, 4I11/2, 4I9/2, 4F9/2, 4S3/2, 2H11/2, 4F7/2, 4F5/2, 2H9/2, 4G11/2 and 4G9/2. Other absorption bands are invisible due to the strong intrinsic absorption for present glass. Even though with a relatively weak absorption band at ~808 nm, 4I9/2 level of Er3+ could be resonant with this absorption band. Therefore, this glass could be pump under excitation of 808 nm LD.

As indicated in the inset of Fig.1, the transmittance reaches as high as 90% and extends up to 5.5 μm. The concave existed around 3000 nm is ascribed to typical H2O absorption band. It is widely recognized that the OH− group is responsible to the absorption loss and plays as quenching center that reduces 2.7 μm emission intensity and lifetime14,22. Thus glass with low OH− group concentration is expected for mid-infrared laser application.

The infrared absorption coefficient αOH determined from the transmittance spectrum is commonly utilized to represent OH− group concentration. By using exponential form of Beer’s law22:

Where l, T0 and T represent sample thickness (cm), the maximum transmittance (%) of the glass matrix and the transmittance (%) at 3.0 μm, the Avogadro constant respectively. It was calculated to be 0.674 cm−1 in 50 T-7Er glass, which is quite low compared with 1.09 cm−1 TY-4 glass21 and 0.75 cm−1 of TZN glass23. Therefore, the host of oxyfluoride tellurite has a considerably low loss band around 3.0 μm, enabling Er3+ to emit at ~2.7 μm.

Judd-Ofelt parameters and radiative properties

Judd-Ofelt (J-O) theory is an effective way to investigate the local structure and boding in the vicinity around rare-earth ions24,25. The parameters needed for Judd-Ofelt calculation are listed in Table 1. According to the absorption spectrum, three J-O intensity parameters Ωt (t = 2, 4, 6) were calculated. The Ω2 = 6.0 ×10−20 cm2, Ω4 = 1.45 × 10−20 cm2, Ω6 = 1.12 × 10−20 cm2 and the root mean square error δ = 0.34 × 10−6 are in well agreement with fluorotellurite glass26 and TWPF glass27 which indicates the validity of the Judd-Ofelt theory for predicting the spectral intensities of Er3+. The Ω2 is mostly sensitive to local structure and glass composition. The large value suggests a predominate environment of covalency and asymmetry between rare earth ions and ligands. The Ω4, Ω6 are related to the rigidity of the host and mostly dependent on bulk properties28.

Using the phenomenological J-O parameters, refractive indexes and the equations29,30, the calculated absorption line strength (Sed), calculated predicted spontaneous transition probability (A), radiative lifetime (τrad) and branching ratio (β) of certain optical transitions for 50 T-7Er glass in this study were calculated and shown in Table 2. The A and τrad of 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 transition are crucial parameters for 2.7 μm emission and both relative to the Ω2 and refractive index. With large Ω2 and refractive index of 50 T-7Er glass, large A (39.97 s−1) is obtained and higher than that of Er3+-Ho3+ co-doped ZBAY glass31 (25.11 s−1). It is well known that higher spontaneous transition probability provides a better opportunity to obtain laser actions32. Therefore this present 50 T-7Er glass could be used as 2.7 μm laser material.

Mid-infrared fluorescence properties

The mid-infrared emission spectra of 50 T glasses doped with 1 mol% to 9 mol% Er3+ under 808 nm excitation were measured and displayed in the Fig. 2. It can be see that there is intense peak occurring at 2709 nm which attributes to the radiative transition of Er3+: 4I11/2 → 4I13/2. And the evolution of luminescence intensity is primarily due to the increment of Er3+ concentration. The intensity exhibits an increase tendency with the increment of Er3+ concentration before reaching to saturation when Er3+ is above 7 mol%. Even through the Er3+ exceeds 7 mol%, the concentration quenching phenomenon occurs weakly. Therefore, the beneficially high doping Er3+ concentration (7 mol%) indicates that the present 50 T host glass is suitable for mid-infrared laser application. It is also clear that there is nearly no change in the line-shape and peak wavelength in all samples.

Important parameters that used to estimate the emission ability of luminescent center for 2.7 μm emission (transition 4I11/2 → 4I13/2) include emission cross section (σem), absorption cross section (σabs), effective full width at half-maximum (Δλeff) and product of σem × Δλeff. The Δλeff was obtained by the 2.7 μm emission spectra shown in Fig. 2. The σem could be calculated via Füchtbauer-Ladenburg equation33. Moreover, according to the calculated σem for 2.7 μm emission, the σabs could be obtained via McCumber theory34.

Where Arad is the spontaneous transition probability, I(λ) is the fluorescence spectra intensity, λ is the wavelength, n and c represent the refractive index and the speed of light, Zl and Zu are partition functions of the lower and upper manifolds, respectively.

Figure 3 displays the σabs (peak value is 8.75×10−21 cm2) and σem (peak value is 10.18 × 10−21 cm2) of 2.7 μm emission for prepared 50 T-7Er glass. In addition, the product of σem × Δλeff (945.32 × 10−28 cm3) was calculated to assess the bandwidth property of the optical amplifier. Table 3 lists the values of these parameters in various Er3+ doped glasses for comparison. Results indicate that the developed glass has promising potential for mid-infrared applications.

In order to further evaluate the broadband emission performance of 50 T-7Er glass, it is possible to calculate the net gain coefficient G(λ) according to the following equation6:

Where N is the doping concentration of Er3+ (13.702 × 1020 ions/cm−3 for 50 T-7Er glass), P is the population inversion. The 2.7 μm G(λ) with different P value of 50 T-7Er glass as the function of wavelength is depicted in Fig. 4. As shown in the diagram, when the P is 0.5, the G(λ) becomes positive number and is 1.28 cm−1. Additionally, the G(λ) has a maximum of 13.95 cm−1 when the P is 1. These values are higher than fluorotellurite glass35. All of these parameters that mentioned above indicate that the developed glass has promising potential as gain medium for broadband amplifier.

Additionally, the mid-infrared emission spectrum of 50 T-7Er glass under 980 nm excitation was also investigated. The σem of 2.7 μm emission under 980 nm excitation was calculated to be 10.36 × 10−21 cm2, which is comparable with that under 808 nm excitation. However, the Δλeff of 50 T-7Er glass under 980 nm excitation was 80.62 nm, leading to a smaller product of σem × Δλeff (835.22 × 10−28 cm3) than that under 808 nm excitation. Therefore, in present glass system, 808 nm excitation is preferred than 980 nm excitation.

Energy transfer dynamics and rate equation analysis

For the purposes of investigating the energy transfer dynamics, 1.53 μm emission spectra and 980 nm emission spectra with different Er3+ concentration were measured under 808 nm excitation and shown in the Fig. 5(a,b) respectively. No band shift but intensity change can be observed in both of the two diagrams due to the variation of Er3+ concentration. And according to the Fig. 5(c), which is the dependence of intensity on concentration for 2.7 μm, 1.53 μm and 980 nm emission, the 1.53 μm emission has a quenching concentration of 3 mol% Er3+. It is interesting that the 980 nm emission has a similar tendency with 2.7 μm emission. Basing on the luminescent behaviors, the involved energy level diagram is shown in the Fig. 5(d). The energy transfer route should be:

(1). Er3+ ions are initially excited by ground state absorption (GSA) of pumping 808 nm energy to 4I9/2 state from 4I15/2 state.

(2). Due to the narrow energy gap between 4I9/2 state and 4I11/2 state, the electrons of 4I9/2 state are easily depraved to 4I11/2 state by multi-phonon relaxation (MPR).

(3). While some electrons in 4I11/2 state partly relax to 4I13/2 state with a radiative emission of 2.7 μm by transition of Er3+: 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 + 2.7 μm photon.

(4). Or partly relax to 4I15/2 state with a radiative emission of 980 nm by transition of Er3+: 4I112 → 4I15/2 + 980 nm photon.

(5). Then the populated 4I13/2 state yields 1.53 μm emission by transition of Er3+: 4I13/2 → 4I15/2 + 1.53 μm photon.

Additionally, three other processes play an important role in changing the population of Er3+: 4I11/2 state and 4I13/2 state, therefore, affecting the emission intensity of corresponding states. They are:

(6). Energy transfer process (ET) of Er3+: 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 + OH−.

(7a). Energy transfer up-conversion process (ETU1): Er3+: 4I13/2 + 4I13/2 → 4I9/2 + 4I15/2.

(7b). Energy transfer up-conversion process (ETU2): Er3+: 4I11/2 + 4I11/2 → 4F7/2 + 4I15/2.

It has known that main factors of affecting 2.7 μm emission intensity are the populations of Er3+: 4I11/2 state and 4I13/2 state. Since Er3+ doping concentration would no obviously alter the OH− content, it should be the energy transfer up-conversion processes that are altered by Er3+ doping concentration. With the increment of Er3+ doping concentration, energy transfer up-conversion processes are supposed to change correspondingly, resulting in an obvious effect on the populations of 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 states. According to the luminescent behaviors, it is thought that when the Er3+ concentration is up to 7 mol%, the maximum population gap between the 4I11/2 state and 4I11/2 state is obtained. Therefore, the 50 T-7Er glass has strongest 2.7 μm emission intensity among the prepared samples.

To quantitatively improve the hypothesis, rate equations of the system by using the decay performance are carried out. For the purpose of simplifying calculation, we assumed that four main energy states N1, N2, N3 and N4 represent the states of 4I15/2, 4I13/2, 4I11/2 + 4I9/2 and 4S3/2 + 2H11/2 + 4F7/2 states (as shown in Fig. 6). And after excitation of 808 nm LD, all the Er3+ ions distribute among the four energy states, therefore, particle number of Er3+ ions equals to population of N1 + N2 + N3 + N4. The rate equations for our model are:

Where Ip is the intensity of the pump light and equals to 7.22 W/cm2 for 808 nm LD in present work. hνp is the photon energy of the pump radiation. R = σabs(Ip/hνp) is the pump rate (s−1). Wij is the total energy transfer rate from upper i state to lower j state (including radiative and non-radiative transfer processes). WETU is the energy transfer up-conversion rate. τ2 is the measured lifetime of 4I13/2 state under 808 nm LD excitation a. τ3 is the measured lifetime of 4I11/2 state under 808 nm LD excitation. The details of measured lifetimes are displayed in Table 4.

Take the ETU1 process of 4I13/2 state as example. Yamauchi assumed that no other processes influence the population of state N2 after the pump power is turn off (R = 0) and Eqs.(6) could be simplified as36:

Then solve Eqs.(9), we can obtain the following function expression:

Where N2(0) is population of 4I13/2 state after the pump power is turn off. Then by solving the Eqs.(10) in steady-state condition, we can get the equation:

The parameters energy transfer up-conversion rate of 4I13/2 state (WETU1) could be obtained by fitting Eq.(11) to the normalized fluorescence decay curves of 4I13/2 state. The results are shown in Fig. 7. Seen from the figure, the fitting curves match well with the measured lifetimes, illustrating the validity of fitting procedure. The fitting procedure of ETU2 process is similar with that of ETU1 process, therefore, we would not discuss in detailed.

The dependence of WETU on Er3+ concentration are shown as the Fig. 8. It is obvious that the WETU1 of 4I13/2 state substantially increases with the increment of Er3+ concentration. The increase of WETU1 is advantageous to deplete the ions in 4I13/2 state by transferring energy to adjacent state. In parallel, the WETU2 of 4I11/2 state reduces with the increment of Er3+ concentration. The lower WETU2 makes more ions aggregated in 4I11/2 state. Therefore the population inversion between the 4I11/2 and 4I13/2 state is deeply improved and the 2.7 μm emission is enhanced with the increment of Er3+ concentration.

Conclusion

In summary, a detailed investigation of Er3+ doped oxyfluoride tellurite glasses with molar compositions of 50TeO2 - 39RF2 (R = Ba, Mg, Zn) - 3NaF - 8 YF3 - xErF3 (x = 1, 3, 5, 7, 9) is carried out. Judd-Ofelt intensity parameters and radiative properties of 50 T-7Er glass are calculated and discussed. Emission spectra consisted of 2.7 μm, 1.53 μm and 980 nm emission under 808 nm excitation are investigated. The results indicate that 50 T-7Er glass is a potential candidate for mid-infrared laser application. A possible energy transfer mechanism is proposed basing on the luminescence behaviors and the rate equation analysis is made to quantitatively prove it. With the increment of Er3+ concentration, the energy transfer up-conversion rate WETU1 of 4I13/2 state increases while the energy transfer up-conversion rate WETU2 of 4I112 state reduces, leading a increment of population inversion between the two states. Therefore, the 2.7 μm emission is enhanced with the increment of Er3+ concentration.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, F. et al. Investigation of mid-infrared emission characteristics and energy transfer dynamics in Er3+ doped oxyfluoride tellurite glass. Sci. Rep. 5, 10676; doi: 10.1038/srep10676 (2015).

References

Seddon, A. B., Tang, Z., Furniss, D., Sujecki, S. & Benson, T. M. Progress in rare earth doped mid-infrared fiber lasers. Opt. Express 18, 26704–26719 (2010).

Jackson, S. D. Towards high-power mid-infrared emission from a fiber laser. NAT Photonics 6, 423–431 (2012).

Stoneman, R. C., Lynn, J. G. & Esterowitz, L. Direct upper-state pumping of the 2.8 μm Er3+:YLF laser, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 28, 1041 (1992).

Quimby, R. S., Miniscalco, W. J. & Thompson, B. Excited state absorption at 980 nm in erbium doped glass, in Fiber Laser Sources and Amplifiers III, Proc. SPIE 1581, 72–79 (1991).

Bedo, S., Pallnau, M., Luthy, W. & Werber, H. P. Saturation of the 2.71 μm laser output in erbium doped ZBLAN fibers, Opt. Commun. 116, 81 (1995).

Wang, R. et al. Heavily erbium-doped low-hydroxyl fluorotellurite glasses for 2.7 μm laser applications. Opt. Mater. Express. 3, 1127–1136 (2013).

Huang, F., Liu, X., Li, W., Hu, L. & Chen, D. Energy transfer mechanism in Er3+ doped fluoride glass sensitized by Tm3+ and Ho3+ for 2.7 μm emission. Chin. Opt. Lett. 12, 051601 (2014).

Tian, Y., Xu, R., Zhang, L., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Observation of 2.7 μm emission form diode-pumped Er3+/Pr3+ codoped fluorophosphates glass. Opt. Lett. 36, 109–111 (2011).

Li, X., Liu, X., Zhang, L., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Emission enhancement in Er3+/Pr3+-codoped germanate glasses and their use as a 2.7 μm laser material. Chin. Opt. Lett. 11, 121601 (2013).

Lin, H., Chen, D., Yu, Y., Yang, A. & Wang, Y. Enhanced mid-infrared emissions of Er3+ at 2.7 μm via Nd3+ sensitization in chalcohalide glass. Opt. Lett. 36, 1815–1817 (2011).

Wei, T. et al. Mid-infrared fluorescence, energy transfers process and rate equation analysis in Er3+ doped germanate glass. Sci. Rep 4, 0606 1–10 (2014).

Zhou, P., Wang, X., Ma, Y., Hu, L. & Liu, Z. Review on recent progress on mid-infrared fiber laser. Las. Phy. 22, 1744–1751 (2012).

Sojka, L. et al. Broadband, mid-infrared emission from Pr3+ doped GeAsGaSe chalcogenide fiber, optically clad. Opt. Mater. 36, 1076–1082 (2012).

Wang, P., Li, W., Peng, B. & Lu, M. Effect of dehydration techniques on the fluorescence spectral features and OH absorption of heavy metals containing fluoride tellurite glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 358, 788–793 (2012).

Ma, Y., Guo, Y., Huang, F., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Spectroscopic properties in Er3+ doped zinc- and tungsten-modified tellurite glass for 2.7 μm laser materials. J. Lumin 147, 372–377 (2014).

Zhang, H., Zhou, Z., He, J. & Lin, A. Intense 2.7 μm emission of Er3+-doped water-free fluorotellurite glasses. Opt. Lett. 37, 3408–3410 (2012).

Zhang, F. et al. Enhanced 2.7 μm emission from Er3+ doped oxyfluoride tellurite glasses for a diode-pump mid-infrared laser,” AIP Adv. 4, 047101 1–11 (2014).

Xu, S., Wang, P., Zheng, R., Wei, W. & Peng, B. Effects of alkaline-earth fluorides and OH− on spectroscopic properties of Yb3+ doped TeO2-ZnO-B2O3 based glass. J. Lumin. 140, 26–29 (2013).

Koide, M., Matusita, K. & Komatsu, T. Viscosity of fluoride glasses at glass transition temperature. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 125, 93–97 (1990).

Cai, M. et al. Analysis of energy transfer process based emission spectra of erbium doped germinate glasses for mid-infrared laser materials. J. Alloys. Compd. 626, 165–172 (2015).

Monteiro, G., Li, Y., Santos, L. & Almeida, R. Optical and spectroscopic properties of rare earth-doped (80-x)TeO2-xGeO2-10Nb2O5-10K2O glasses. J. Lumin. 134, 284–296 (2013).

Guo, Y., Tian, Y., Zhang, L., Hu, L. & Zhang, J. Erbium doped heavy metal oxide glasses for mid-infrared laser materials. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 377, 119–123 (2013).

Gomes, L., Lousteau, J., Milanese, D., Mura, E. & Jackson, S. Spectroscopy of mid-infrared (2.9 μm) fluorescence and energy transfer in Dy3+–doped tellurite glass. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 31, 429–435 (2014).

Judd, B. R. Optical absorption intensities of Rare-Earth Ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761 (1962).

Ofelt, G. S. Intensity of Crystal Spectra of Rare-Earth Ions. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 511–520 (1962).

Zhou, B. et al. Intense near-infrared emission of 1.23 μm in erbium-doped low-phonon-energy fluorotellurite glass. Spectrochim. Acta. Part. A. 111, 49–53 (2013).

Balda, R., Al-Saleh, M., Miguel, A., Fdez-Navarro, J. & Fernández, J. Spectroscopy and frequency upconversion of Er3+ ions in fluorotellurite glasses. Opt. Mater. 34, 481–486 (2011).

Desirena, H., Rosa, E. D., Diza-Torres, L. A. & Kumar, G. A. Concentration effect of Er ion on the spectroscopic properites of Er3+ and Yb3+/ Er3+ co-doped phosphate glasses. Opt. Mater. 28, 560–568 (2006).

Mahmoud, K., El-Bahy, Z. & Hanafy, A. Photoluminescence analysis of Er3+ nanoparticles in cadmium-phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 363, 116–120 (2013).

Sdiri, N., Elhouichet, H., Barthou, C. & Ferid, M. Spectroscopic properties of Er3+ and Yb3+ doped phosphate–borate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 1010, 85–90 (2012).

Huang, F. et al. Sensitizing effect of Ho3+ on the Er3+: 2.7 μm -emission in fluoride glass. Opt. Mater. 36, 921–925 (2014).

Heo, J., Shin, Y. & Jang, J. Spectroscopic analysis of Tm3+ in PbO-Bi2O3-Ga2O3 glass. Appl. Opt. 34, 4284–4289 (1995).

Payne, S., Chase, L., Smith, L., Kway, W. & Krupke, W. Infrared cross-section measurements for crystals doped with Er3+, Tm3+ and Ho3+. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 28, 2619–2630 (1992).

McCumber, D. Theory of Phonon-Terminated Optical Masers. Phy. Rev. 136, A299–306 (1964).

Ma, Y. et al. Mid-infrared 2.7um emission properties of Er3+ sensitized by Nd3+ in fluorotellurite glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 369, 23–28 (2013).

Yamauchi, H., Murugan, G. & Ohishi, Y. Optical properties of Er3+ and Tm3+ ions in a tellurite glass. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 043505 (2005).

Huang, F., Li, W., Hu, L. & Chen, D. Physical, chemical and optical properties of Er3+-doped low Al(PO3)3/Al(H2PO4)3 modified fluoroaluminate glasses for 2.7 μm application. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 31, 1137–1144 (2014).

Shi, D. et al. Effects of alkali ions on thermal stability and spectroscopic properties of Er3+-doped gallogermanate glasses. Physica B. 406, 628–632 (2011).

Guo, Y., Gao, G., Li, M., Hu L. & Zhang, J. Er3+-doped fluoro-tellurite glass: A new choice for 2.7 μm lasers. Mater. Lett. 80, 56–58 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY13F050003, R14E020004 and LY14B010004), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.61308090, 61405182, 51372235, 51472225, 51172252 and 51272243), overseas students preferred funding of activities of science and technology project, International S&T Cooperation Program of China 2013DFE63070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z.C. wrote the main manuscript text. T.W., X.F.J. and J.J.Z. checked up. Y.T. and S.Q.X. are responsible for the experiment. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Wei, T., Jing, X. et al. Investigation of mid-infrared emission characteristics and energy transfer dynamics in Er3+ doped oxyfluoride tellurite glass. Sci Rep 5, 10676 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10676

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10676

This article is cited by

-

The effect of cobalt/copper ions on the structural, thermal, optical, and emission properties of erbium zinc lead borate glasses

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Synthesis, Optical Absorption and Radiation Shielding Performance of Sodium Zinc Borate-Er2O3 Glasses

Journal of Electronic Materials (2021)

-

Fluoroindate glasses co-doped with Pr3+/Er3+ for near-infrared luminescence applications

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Anti-escaping of incident laser in rare-earth doped fluoride ceramics with glass forming layer

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

2.8 μm emission and OH quenching analysis in Ho3+ doped fluorotellurite-germanate glasses sensitized by Yb3+ and Er3+

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.