Abstract

InGaN-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have been widely accepted as highly efficient light sources capable of replacing incandescent bulbs. However, applications of InGaN LEDs are limited to small devices because their fabrication process involves expensive epitaxial growth of InGaN by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy on single-crystal wafers. If we can utilize a low-cost epitaxial growth process, such as sputtering on large-area substrates, we can fabricate large-area InGaN light-emitting displays. Here, we report the growth of GaN (0001) and InGaN (0001) films on amorphous SiO2 by pulsed sputtering deposition. We found that using multilayer graphene buffer layers allows the growth of highly c-axis-oriented GaN films even on amorphous substrates. We fabricated red, green and blue InGaN LEDs and confirmed their successful operation. This successful fabrication of full-color InGaN LEDs on amorphous substrates by sputtering indicates that the technique is quite promising for future large-area light-emitting displays on amorphous substrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Group III nitride semiconductors are attractive materials for high efficiency light-emitting diodes (LEDs) because of their excellent optical and electrical properties1,2. To date, most of the InGaN-based LEDs have been fabricated on single-crystal substrates, such as sapphire and SiC, because of their high crystallinity. However, applications of InGaN-based LEDs are often restricted by the small diameter and high cost of these wafers. Numerous attempts have been made to replace single-crystal substrates for the growth of group-III nitrides with low-cost, large-area materials such as glass, metal and various oxides3,4,5,6,7. Among these candidates, glass is an ideal substrate material for large-area, low-cost LEDs because of its transparency and compatibility with existing liquid-crystal display (LCD) fabrication processes. Despite these advantages, GaN films grown on glass have not been practical because of two serious problems. The first is the amorphous nature of glass, which leads to poor crystalline quality of the overlaid nitride semiconductor layer. To overcome this problem, a highly oriented crystalline buffer layer can be introduced between the substrate and nitride film. Multilayer graphene is one of the most suitable materials because large-area graphene films with highly oriented structures can be easily deposited by conventional chemical vapor deposition (CVD)8,9. The other problem is a low softening temperature (500–700 °C) for glass substrates. Since the substrate temperature for GaN growth usually needs to be above 1000 °C for conventional metalorganic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), it is impossible to use glass substrates for GaN growth by MOCVD. Nevertheless, recent progress in the epitaxial growth techniques based on pulsed sputtering deposition (PSD) enables the growth of high-quality group III nitride crystals even at room temperature10. The successful reduction in the growth temperature was achieved because of the high kinetic energy and pulsed supply of group III atoms, which assist the surface migration of film precursors at substrate surfaces11. Recently, successful fabrication of 640 nm InGaN LEDs by PSD at a maximum process temperature of 480 °C has been reported12.

In this study, we grew group III nitride films on amorphous SiO2 using multilayer graphene buffer layers; the use of multilayer graphene buffer layers drastically improved the crystalline quality of the GaN films on the amorphous substrates. LEDs fabricated on GaN films with multilayer graphene buffer layers exhibited clear electroluminescence (EL) emissions with colors from blue to red. These results indicate that the present technique is quite promising as a future fabrication method for large-area InGaN light-emitting displays on amorphous substrates.

The multilayer graphene layers were grown by CVD on Ni foil and transferred onto amorphous fused silica substrates or amorphous SiO2 prepared by thermal oxidation of Si13,14. Before the growth of the group-III nitride films, the multilayer graphene layers on amorphous SiO2 were heated at 600 °C for 30 min in vacuum. Then, 50-nm-thick AlN initial layers were deposited, followed by 1000-nm-thick GaN layers. All nitride films were grown by PSD, which has been described previously10,12,15, with a growth rate of 1.0–2.0 μm/h at substrate temperatures of 550–760 °C. Figure 1(a) shows a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a GaN film grown without a multilayer graphene buffer layer. The surface consists of randomly oriented grains, with sizes of the order of several hundred nanometers. In contrast, as shown in Figure 1(b), the GaN film with the multilayer graphene buffer layer has a smooth surface morphology. The crystal orientations of the GaN films were investigated by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). Figure 2 shows {0002} and  EBSD pole figures for a 20 × 20 μm2 area on the GaN films grown on SiO2 (a) without and (b) with multilayer graphene buffer layers. The GaN films prepared without the multilayer graphene buffer layer showed broad spots in the {0001} pole figure and ring-shaped patterns in the

EBSD pole figures for a 20 × 20 μm2 area on the GaN films grown on SiO2 (a) without and (b) with multilayer graphene buffer layers. The GaN films prepared without the multilayer graphene buffer layer showed broad spots in the {0001} pole figure and ring-shaped patterns in the  pole figure, which is consistent with the randomly oriented small grains observed using SEM. In contrast, the {0001} spots for the GaN films prepared with multilayer graphene buffer layers were small and the

pole figure, which is consistent with the randomly oriented small grains observed using SEM. In contrast, the {0001} spots for the GaN films prepared with multilayer graphene buffer layers were small and the  pole figure showed a clear six-fold rotational symmetry. This indicates that the crystalline quality of the GaN films was drastically improved by the use of multilayer graphene buffer layers. This improvement in the crystalline quality of the GaN films can be attributed to the epitaxial growth of GaN on the highly oriented multilayer graphene; it has been reported that the epitaxial growth of GaN on graphene occurs with the epitaxial relationship GaN(0001)/graphene(0001)16,17.

pole figure showed a clear six-fold rotational symmetry. This indicates that the crystalline quality of the GaN films was drastically improved by the use of multilayer graphene buffer layers. This improvement in the crystalline quality of the GaN films can be attributed to the epitaxial growth of GaN on the highly oriented multilayer graphene; it has been reported that the epitaxial growth of GaN on graphene occurs with the epitaxial relationship GaN(0001)/graphene(0001)16,17.

The crystal structures of GaN/AlN films on amorphous SiO2 substrates with multilayer graphene buffer layers were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The XRD 2θ/ω scan of the films show five peaks, as shown in Figure 3(a) at 2θ = 26.5°, 34.5°, 36.0°, 69.1° and 72.9°, which can be attributed to the diffractions from multilayer graphene 0002, GaN 0002, AlN 0002, Si 004 and GaN 0004, respectively. These results indicate that GaN and AlN grew along the c-axis, which agrees well with the EBSD measurements.

Optical properties of the GaN films with and without graphene buffer layers were investigated by photoluminescence (PL) measurements at room temperature with a He–Cd laser (325 nm) as an excitation source. There are three peaks at approximately 360 nm, 380 nm and 550 nm for the GaN films grown without multilayer graphene buffer layers, as shown in Figure 4(a). The PL peak at 360 nm corresponds to the near-band-edge emission from the hexagonal GaN phase. The peak at 380 nm can be attributed to excitonic emission of cubic GaN18,19, which implies the existence of stacking faults. A broad region of the PL spectrum at 550 nm is defect-related yellow luminescence of GaN20. On the other hand, the room-temperature PL spectrum in Figure 4(b) of a GaN film with a multilayer graphene buffer layer shows only one peak at 360 nm. The emissions at 380 nm and 550 nm were negligibly small. These PL results strongly support the notion that the crystalline quality of a GaN film grown by PSD on amorphous SiO2 is considerably improved by the use of a multilayer graphene buffer layer.

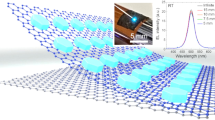

To confirm the high crystallinity of PSD nitride films prepared on amorphous substrates, we fabricated LEDs using InGaN/multilayer on the AlN/graphene/amorphous SiO2 structures. For the InGaN LED, five periods of alternating InGaN/GaN multiple quantum wells (MQWs) were grown on a 1-μm-thick n-type GaN layer and were topped by a Mg-doped p-type GaN layer. The thickness of the MQW periodic structure and p-type GaN layer were 70 nm and 600 nm, respectively. The thick p-type layer was used to keep the surfaces of the LED structures smooth. Clear satellite peaks around the GaN 0002 diffraction peak in the XRD curves in Figure 5(a) indicate the smoothness and abruptness of the heterointerfaces in the MQWs. The fitting of the experimental XRD curves to the theoretical curves revealed that the MQWs consisted of 3.1-nm-thick In0.21Ga0.79N wells and 8.6-nm-thick GaN barriers. Figure 5(b) shows a typical room-temperature PL spectrum measured with a 405-nm violet laser as an excitation source. Green PL was clearly observed with a peak wavelength of 520 nm. We investigated temperature dependence of the PL spectrum from 300 K to 13 K for the green MQW prepared on amorphous SiO2 with a multilayer graphene buffer layer. Figure 5(c) shows the temperature dependence of the integrated PL intensity measured at an excitation laser intensity of 15 mW/cm2. The ratio of the integrated PL intensity at 13 K to that at 300 K was 7.4%, which is comparable with the value for conventionally fabricated green LEDs on sapphire substrates21,22. Since this value is often considered a rough indicator of the internal quantum efficiency23, we can infer that the optical properties of our film were not seriously degraded by the use of an amorphous substrate. Also, the integrated intensity of PL from the green MQW structure on amorphous SiO2 with a multilayer graphene buffer layer was approximately 14% of that from a commercially available reference MOCVD blue MQW on single-crystal sapphire substrates, measured with the same optical setup. Since the internal quantum efficiency of the reference blue MQW sample used in this study was approximately 50% from the temperature dependence of the PL intensity, this comparison is consistent with the data of the temperature dependence measurements.

(a) XRD 2θ/ω curve and (b) a room-temperature green PL spectrum for an LED structure fabricated on amorphous SiO2 with a multilayer graphene buffer layer. A PL spectrum for a commercially available blue LED on single-crystal sapphire is also shown in this figure. (c) Temperature dependence of the integrated PL intensity for the range of 13–300 K.

After the deposition of Pd/Au and In electrodes on the p- and n-type GaN surfaces, respectively, EL measurements were performed on the LED structures shown in Fig. 6 (a). As shown in Figure 6(b), green LEDs operated normally with reasonable emission spectra and the intensity increased with an increase in injection current from 2.1 to 10.8 mA. We also fabricated blue and red LEDs by changing the In composition in the PSD-InGaN layers and both operated effectively, as shown in Figure 6(c).

By demonstrating that full-color LEDs can be fabricated on amorphous substrates, we suggest that since sputtering is very frequently used in the LCD industry, it is an established process that could be adapted to fabricate large-area inorganic LED displays on glass substrates. It should also be noted that state-of-the-art technology in the glass industry can offer roll-to-roll processing of flexible glass foils24. We think the combination of these techniques can lead to the development of large-area flexible inorganic devices.

References

Nakamura, S. et al. K. InGaN/GaN/AlGaN-based laser diodes with modulation-doped strained-layer superlattices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 36, L1568 (1997).

Akasaki, I. & Amano, H. Crystal growth and conductivity control of group III nitride semiconductors and their application to short wavelength light emitters. Jpn. J. Apppl. Phys. 36, 5393 (1997).

Bour, D. P. et al. Polycrystalline nitride semiconductor light-emitting diodes fabricated on quartz substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 2182 (2000).

Guha, S. & Bojarczuk, N. A. Ultraviolet and violet GaN light emitting diodes on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 415 (1998).

Kobayashi, A., Fujioka, H., Ohta, J. & Oshima, M. Room temperature layer by layer growth of GaN on atomically flat ZnO. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 43, L53 (2004).

Ohta, J., Fujioka, H. & Oshima, M. Room-temperature epitaxial growth of GaN on conductive substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 3060 (2003).

Inoue, S., Okamoto, K., Nakano, T., Ohta, J. & Fujioka, H. Growth of single crystalline GaN on silver mirrors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 201920 (2007).

Chung, K., Lee, C. H. & Yi, G. C. Transferable GaN layers grown on ZnO-coated graphene layers for optoelectronic devices. Science 330, 655 (2010).

Chung, K., Park, S. I., Baek, H., Chung, J.-S. & Yi, G.-C. High-quality GaN films grown on chemical vapor-deposited graphene films. NPG Asia Materials 4, e24 (2012).

Sato, K., Ohta, J., Inoue, S., Kobayashi, A. & Fujioka, H. Room-temperature epitaxial growth of high quality AlN on SiC by pulsed sputtering deposition. Appl. Phys. Express 2, 011003 (2009).

Okubo, K., Kobayashi, A., Ohta, J., Oshima, M. & Fujioka, H. Electron mobility of ultrathin InN on yttria-stabilized zirconia with two-dimensionally grown initial layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 022103 (2013).

Nakamura, E., Ueno, K., Ohta, J., Fujioka, H. & Oshima, M. Dramatic reduction in process temperature of InGaN-based light-emitting diodes by pulsed sputtering growth technique. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 051121 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312 (2009).

Yu, Q. et al. Graphene segregated on Ni surfaces and transferred to insulators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 113103 (2008).

Oseki, M., Ohkubo, K., Kobayashi, A., Ohta, J. & Fujioka, H. Field-effect transistors based on cubic indium nitride. Sci. Rep. 4, 3951 (2014).

Ishii, A., Tatani, T., Asano, H. & Nakada, K. Computational study for growth of GaN on graphite as 3D growth on 2D material. phys. stat. sol. (c) 7, 347 (2010).

Ishii, A., Tatani, T., Hirai, S. & Nakada, K. Growth of GaN on graphite substrate as growth on graphene using the density functional theory. AIP Conf. Proc. 1399, 125 (2011).

Strite, S. et al. An investigation of the properties of cubic GaN grown on GaAs by plasma-assisted molecular-beam epitaxy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 9, 1924 (1991).

Menniger, J., Jahn, U., Brandt, O., Yang, H. & Ploog, K. Identification of optical transitions in cubic and hexagonal GaN by spatially resolved cathodoluminescence. Phys. Rev. B 53, 1881 (1996).

Kaufmann, U. et al. Origin of defect-related photoluminescence bands in doped and nominally undoped GaN. Phys. Rev. B 59, 5561 (1999).

Kumar, M. et al. Improved internal quantum efficiency of green emitting InGaN/GaN multiple quantum wells by In prefleow for InGaN well growth. Jpn. J. Appl. Phy. 47, 839842 (2008).

Liu, M., Rong, B. & Salemink, H. Evaluation of LED application in general lighting. Opt. Eng. 46, 074002 (2007).

Hangleiter, A. et al. Towards understanding the emission efficiency of nitride quantum wells. phys. stat. sol. (a) 201, 2808 (2006).

Garner, S. et al. Ultra-slim flexible glass substrates for display applications. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 43, 342 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.F. supervised the project. J.S.W. and J.O. performed film growth and device fabrication. J.O., U.K., A.K. and H.F. designed the experimental procedure. All the authors interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shon, J., Ohta, J., Ueno, K. et al. Fabrication of full-color InGaN-based light-emitting diodes on amorphous substrates by pulsed sputtering. Sci Rep 4, 5325 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05325

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05325

This article is cited by

-

Growth of 12-inch uniform monolayer graphene film on molten glass and its application in PbI2-based photodetector

Nano Research (2019)

-

Direct Growth of III-Nitride Nanowire-Based Yellow Light-Emitting Diode on Amorphous Quartz Using Thin Ti Interlayer

Nanoscale Research Letters (2018)

-

III-nitride core–shell nanorod array on quartz substrates

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Growth of Epitaxial ZnSnxGe1−xN2 Alloys by MBE

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Fabrication of full-color GaN-based light-emitting diodes on nearly lattice-matched flexible metal foils

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

EBSD pole figures for a GaN film grown on amorphous SiO2 (a) without and (b) with a multilayer graphene buffer layer.

EBSD pole figures for a GaN film grown on amorphous SiO2 (a) without and (b) with a multilayer graphene buffer layer.