Abstract

We report on the spreading of triboelectrically charged glass particles on an oppositely charged surface of a plastic cylindrical container in the presence of a constant mechanical agitation. The particles spread via sticking, as a monolayer on the cylinder's surface. Continued agitation initiates a sequence of instabilities of this monolayer, which first forms periodic wavy-stripe-shaped transverse density modulation in the monolayer and then ejects narrow and long particle-jets from the tips of these stripes. These jets finally coalesce laterally to form a homogeneous spreading front that is layered along the spreading direction. These remarkable growth patterns are related to a time evolving frictional drag between the moving charged glass particles and the countercharges on the plastic container. The results provide insight into the multiscale time-dependent tribolelectric processes and motivates further investigation into the microscopic causes of these macroscopic dynamical instabilities and spatial structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Granular materials often acquire charge due to triboelectric processes1,2,3,4. The resulting effect is seen in a wide variety of phenomena ranging from the very commonplace observation of food grains sticking on to their containers to problems of practical importance, e.g., sticking of pharmaceutical powders to tablet presses5,6, particles sticking to the walls of pneumatic transport lines7 and adhesion of toner particles in electrophotography8. The complexities associated are diverse. At a single particle scale, they are manifested through the microscopic charge transfer mechanism1,2,3,4 and at larger scales, the collective response of the particles is related to the long range electrostatic interactions5, that can lead to clumping6 and pattern formation7.

The motion of these particles on a substrate in response to external forcing is governed by the particle-substrate frictional interactions which relate to both the dissipative and the adhesive parts of the particle-substrate interaction8. In this paper we find that constant mechanical agitation modifies this frictional interaction over time. This is reflected in both the positional rearrangement and the motion of the particles on the substrate.

Experimental setup

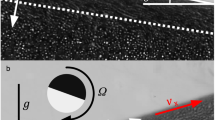

An orbital shaker from Heidolph Instruments produces triboelectric charging in a cylindrical container (vial) made of polypropylene (PP) or polystyrene (PS) (diameter 2R = 16 mm) containing 104 glass particles. The shaker makes the vial move in a circle (radius a = 2.5 mm and at a frequency f) without spinning about its axis (Fig. 1A bottom panel). The spreading phenomena observed in both PP and PS vials are qualitatively similar (Supplementary Movie SM1). The specific vial for which the data are presented is mentioned in the text and figure captions. We use three kinds of imaging: (i) continuous (ii) dynamic and (iii) static for observing different aspects of the kinetics of the system. The continuous images are obtained using a fast camera (Phantom M310). The other images, i.e., dynamic and static are obtained using the camera EHD UK-1157. In the dynamic case, the system is imaged stroboscopically while in motion, at a specific location in its orbit. This is achieved by periodically triggering the camera with an electrical pulse generated by a position sensor (TCRT 5000). In contrast, the static images are obtained by temporarily pausing the drive and bringing the system to rest, following which the drive is resumed. The specific mode of imaging is explicitly mentioned in the text as well in the relevant figure captions. The orbital motion produces a potential well whose minima moves azimuthally along the surface of the cylinder in a periodic manner. This is reflected in the motion of the granular heap (see Fig. 1 A top panel), as observed by continuous imaging. The average charge acquired by the glass particles in the experiment is measured by pouring the particles into a Faraday cup connected to a Keithley 6514 system electrometer.

Spreading dynamics.

(A) Bottom panel: The experimental setup consists of a cylindrical polypropylene vial of diameter (2R = 16 mm) containing 104 glass particles (average diameter d = 300 μm polydispersity = 20% and average individual mass m = 40 μg)) whose center (marked by a cross) moves on a circular orbit (dashed line) of diameter (2a = 5 mm) at a constant frequency f. The orbital motion is achieved using an orbital shaker. (A) Top Panel: The granular heap as imaged in the continuous mode at six equally spaced time intervals in one period (T = 1/f). (B) Typical images (dynamic mode) of the vial (polypropylene) taken at certain instances of times (marked in the sequence), while it is in orbital motion at f = 14 Hz. The lines in white outlines the heap of particles formed due to inertial force arising out of the orbital motion. (C) The evolution in time of the number density of particles <n(h)> as a function of height. The numerical value of <n(h)> is color-coded. The growth regimes I and II are marked. (D) The variation of hin as a function of the square of frequency of orbital motion for glass particles (GP) in polypropylene (PP) vial (gray circles), GP in polystyrene (PS) vial (black circles) and water (W) in PP (open squares). (E) The variation of  as a function of frequency for glass particles in polypropylene (PP, black circles) and polystyrene (PS, open circles) vials. The solid line has a slope of −2 in the log-log axis, i.e.,

as a function of frequency for glass particles in polypropylene (PP, black circles) and polystyrene (PS, open circles) vials. The solid line has a slope of −2 in the log-log axis, i.e.,  .

.

Results

The constant rubbing of the heap against the vial surface leaves both the glass particles and the vial surface triboelectrically charged. For the present experiments, we find that rubbing leaves the glass particles with an overall positive charge (measured average charge per particle ~10−13 C) while the surface of the vial is oppositely (negatively) charged. The time evolution of this differential charging modifies the particle-substrate interaction. This causes a fraction of the particles to “stick to the wall” of the vial, albeit moving with a velocity less than 2πRf. The remaining particles continue to move as a heap with a linear velocity of 2πRf, i.e. the heap returns to its initial position after a complete period.

We present our findings in the following sequence. First, we discuss the structural arrangements of the stuck particles both with and without the drive. These arrangements change with time via the spreading of particles on the substrate, which, in turn, redistributes the counter charges (ions). Subsequently, we discuss the migration kinetics of the particle assembly, its relaxation processes and then analyze the motion of a single stuck particle. Finally, we present our results on the in-situ electrical measurements which provide additional information about the charges and their relative motion with respect to the vial.

Overview of the spreading phenomena

The sequence of dynamic images in Fig. 1B (Supplementary Movie: SM1 (Left panel)) captures the evolution of this heap with time (tw) in a PP vial. As particles progressively stick to the surface, their number density spreads in the azimuthal direction and the shape of the heap (marked by lines in white) begins to change. From the dynamic images we compute the variation in the number density of particles with height (h):  . The angular brackets represent an average intensity of the dynamic image, Id(i, h), over the lateral dimension (L) of the image and Id0 corresponds to the intensity of a single particle. The evolution of <n(h)> with tw (Fig. 1C) shows two distinct regimes of spreading, viz., an initial phase (regime I) marked by a slower increase of the spreading front, followed by a more rapidly changing front in the second phase (regime II) that initiates after a characteristic time (

. The angular brackets represent an average intensity of the dynamic image, Id(i, h), over the lateral dimension (L) of the image and Id0 corresponds to the intensity of a single particle. The evolution of <n(h)> with tw (Fig. 1C) shows two distinct regimes of spreading, viz., an initial phase (regime I) marked by a slower increase of the spreading front, followed by a more rapidly changing front in the second phase (regime II) that initiates after a characteristic time ( ). The plateau height hin of the front in regime I scales linearly with the square of the drive frequency (f2), i.e., the force applied, is independent of the particle diameter (d) and the material of the vial. Further, it is found to be approximately the same as that obtained with an equal volume of water replacing the glass particles, as shown in Fig. 1D.

). The plateau height hin of the front in regime I scales linearly with the square of the drive frequency (f2), i.e., the force applied, is independent of the particle diameter (d) and the material of the vial. Further, it is found to be approximately the same as that obtained with an equal volume of water replacing the glass particles, as shown in Fig. 1D.

As more particles stick onto the surface, a dense and amorphous monolayer coverage of the vial surface up to height hin builds up (see Fig. 1B, Supplementary Movies SM1, SM3) and remains nearly saturated for a long time interval. This saturated state in regime I can be thought of as a composite system consisting of stuck particles and their counter charges on the plastic surface. It is from this state in regime I that a new regime II evolves, marked by a further and rapid growth in the front height, a seemingly hithertofore unknown phenomenon which is, however, entirely absent in the same experiment performed on conventional liquids (Supplementary Information: Fig. S1). The crossover time ( ) between regimes I and II depends inversely on the square of frequency, i.e.,

) between regimes I and II depends inversely on the square of frequency, i.e.,  as well as the material properties of the vial (Fig. 1E). For example triboelectric charging is proportional to the difference in the work functions (WF) of the materials involved9. This is consistent with our observation that the crossover time for glass (WF = 5 eV)9 particles in polystyrene (WF = 4.2 eV)10 vials is shorter than that in polypropylene vials (WF = 4.9 eV)9. The data presented in the paper are also sensitive to the humidity in the atmosphere11 and the protocol used for cleaning the surfaces12 implying the importance of the surface charges in the observed phenomenon.

as well as the material properties of the vial (Fig. 1E). For example triboelectric charging is proportional to the difference in the work functions (WF) of the materials involved9. This is consistent with our observation that the crossover time for glass (WF = 5 eV)9 particles in polystyrene (WF = 4.2 eV)10 vials is shorter than that in polypropylene vials (WF = 4.9 eV)9. The data presented in the paper are also sensitive to the humidity in the atmosphere11 and the protocol used for cleaning the surfaces12 implying the importance of the surface charges in the observed phenomenon.

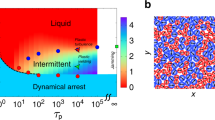

Transverse stripes - precursor to regime II

The onset of regime II is preceded by distinct changes in the structure of the amorphous monolayer of regime I. The dynamic (top panel) and static (bottom panel) images in Fig. 2A (Supplementary Movie SM2) show the appearance of a periodic modulation in particle density in the azimuthal direction (transverse stripes) as observed in a PP vial. The angular distance between the stripes (Λ), increases with f (Fig. 2B) and d (Fig. 2B inset). The stripes are presumably accompanied by the formation of a similarly periodic spatial modulation of counter-charge density on the surface of the vial. This makes the modulation temporally robust and therefore observed in the static images too, as shown in Fig. 2A (bottom panel). The symmetry in the problem, a closed surface with periodic boundary conditions, preferentially supports an integral number of periods of this transverse density modulation. Indeed, for frequencies 14, 30 Hz (Fig. 2B) we observe more pronounced stripes which remain positionally locked in time while for intermediate values of f (20, 25 and 40 Hz in Fig. 2B) the stripes are seen to slide and become substantially weaker in amplitude.

Transverse density modulation.

(A) The appearance of a modulation in the density of stuck particles (d = 300 μm) with a periodicity in the azimuthal angle in polypropylene vial. Top and bottom panel shows static and dynamic images at a sequence of times marked above the images. The periodicity of the modulation depends on the frequency of the orbital motion and the size of the particles. (B) shows this periodic modulation at frequencies 14 Hz, 20 Hz, 25 Hz, 30 Hz and 40 Hz. For certain frequencies (14 Hz, 30 Hz) we observe more pronounced stripes which weaken substantially for intermediate values of f (20 Hz, 25 Hz and 40 Hz). Inset shows the dependence of the wavelength of the periodic modulation, Λ, on the particle diameter, d, at f = 14 Hz.

Vertical streaks - onset of regime II

The formation of regime II is initiated by the emergence of a few-particle-wide vertical streaks that always originate from the tip of the stripes (see the image corresponding to tw = 7000 s in the top panel of Fig. 2A). The large number density of particles in the stripe presumably localizes the charge and thus enhances the emanating electric fields leading to a breakdown-like flow of both particle- and charge-currents which initiates regime II. At long times, however, these streaks gradually diffuse in the transverse direction and eventually merge to form a uniform growing front, as shown in the fourth panel (tw = 9000 s) in Fig. 2A.

Contrast in the structure of the stuck monolayer in the two regimes

In addition to the large change in the front velocity, the two regimes are very different in terms of their growth kinetics and structure. Fig. 3A and B show a sequence of time-lapsed images of the growth in regimes I and II, respectively) in a PP vial. In regime I, the monolayer is formed by random adsorption of particles to the surface of the vial (Supplementary Movie SM3). The monolayer in regime II, in contrast, evolves by sequential adsorption of particles and a layer by layer growth of the spreading front (Supplementary Movie SM4). Furthermore, regimes I and II, yield disordered and layered structures, respectively. Two-dimensional Fast Fourier Transform (2DFFT) images of the two cases are shown, respectively, in the left and right inset of Fig. 3C. The variation of qz and qψ, the wave vectors corresponding to the first peak of the 2DFFT along the axial and circumferential directions respectively, is shown in Fig. 3C. In regime I, (i) the system is isotropic, i.e.,  and (ii) both qz and qψ increase logarithmically in time. But in regime II, (i) the structure near the spreading front is anisotropic, qz < qψ and exhibits periodicity in the axial direction (regions of localized ‘spots’ in the Fourier images) and (ii) qz and qψ remain constant in time. We note that such structural anisotropy has been considered previously in driven disordered media13.

and (ii) both qz and qψ increase logarithmically in time. But in regime II, (i) the structure near the spreading front is anisotropic, qz < qψ and exhibits periodicity in the axial direction (regions of localized ‘spots’ in the Fourier images) and (ii) qz and qψ remain constant in time. We note that such structural anisotropy has been considered previously in driven disordered media13.

Comparison of the growth at small and large times.

In regime I the system grows through random adsorption of particles on the surface of a polypropylene vial. This is shown in the images (static mode) in A. In the later part of regime II, layer by layer growth takes over as is reflected in the sequence in B. (C) The qz (square) and qψ (circle) corresponding to the first peak in the 2DFFT of the structure in regime I and regime II as a function of time. The confidence interval of the data is marked by translucent bands. Left and right insets are examples of 2DFFT obtained in regime I and II respectively. The average of 50 static images ranging over a time ~5000 s, difference between two consecutive static images separated by 100 s and the average of such subtracted images over a time period of ~5000 s are shown in the left, middle and right panels for regime I in D and regime II in E, respectively.

Migration kinetics of the particle in the two regimes

The particle motion in the two regimes depends on the distribution of charge on the substrate which provides the frictional interactions for the particles. To explore their spatial nature, we analyse images from a region closely below the spreading front and examine the following:

-

1

The summed image:

– a superposed sum of the static images, Is(tw). This image captures the different realizations of the configurations of the stuck particles and therefore closely represents the energy landscape associated with the charge distribution on the surface of the vial. The summed image has no distinct structure barring for a hint of granularity in regime I (Fig. 3D left panel), i.e., the stuck particles are sliding in the presence of the drive. In regime II, (Fig. 3E left panel) it has a layered structure with a well-defined periodicity along the vertical axis with no modulation in the azimuthal direction. Since the mobility of the particle in the vertical direction is hindered, we infer the frictional interaction in regime II to be anisotropic (small along the azimuthal direction and large in the axial direction). This is further substantiated from the difference images described below.

– a superposed sum of the static images, Is(tw). This image captures the different realizations of the configurations of the stuck particles and therefore closely represents the energy landscape associated with the charge distribution on the surface of the vial. The summed image has no distinct structure barring for a hint of granularity in regime I (Fig. 3D left panel), i.e., the stuck particles are sliding in the presence of the drive. In regime II, (Fig. 3E left panel) it has a layered structure with a well-defined periodicity along the vertical axis with no modulation in the azimuthal direction. Since the mobility of the particle in the vertical direction is hindered, we infer the frictional interaction in regime II to be anisotropic (small along the azimuthal direction and large in the axial direction). This is further substantiated from the difference images described below. -

2

The difference image: [|Is(tw) − Is(tw + Δtw)|], is taken between two static images separated by a time difference Δtw = 100 s. The bright and dark areas of the difference image below the spreading line correspond to the spatial regions associated with mobile and stagnant particles respectively. For these images, the bright spots are homogenously distributed in regime I (Fig. 3D middle and right panels), while they appear localized in regime II (Fig. 3E middle and right panels). Thus, in regime I, the particles can move isotropically while in regime II particles whose axial motion is restricted coexist with those which can hop between layers. This is also further evidenced by a rougher spreading front in regime I compared to regime II.

-

3

The superposed difference image:

. The superposed difference image (right panel of Fig. 3E) identifies the hopping paths across the layers in regime II through which the particles advect upwards and then sequentially deposit at the top. The averaging over different realizations of configurations ensures that the bright regions in these images correspond to the localised spatial tracks of particles that hop. This form of particle diffusion is characteristic of smectic ordering14. Such localized transport of particles are, however, absent in regime I (right panel of Fig. 3D).

. The superposed difference image (right panel of Fig. 3E) identifies the hopping paths across the layers in regime II through which the particles advect upwards and then sequentially deposit at the top. The averaging over different realizations of configurations ensures that the bright regions in these images correspond to the localised spatial tracks of particles that hop. This form of particle diffusion is characteristic of smectic ordering14. Such localized transport of particles are, however, absent in regime I (right panel of Fig. 3D).

Relaxation dynamics

We now discuss the temporal evolution of the structure of the monolayer of the stuck particles after the drive is switched off. At short times (small values of tw) the particles spread azimuthally and at long times they detach from the surface. These results highlight the role of thermal processes, e.g., diffusion of charge carriers, in the otherwise athermal granular system.

The short time azimuthal spreading happens via a number of transient structures. e.g., chain-like formations (Fig. 4A) in the PS vials and are characterized by the temporal evolution of their average chain length, lchain (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Movie SM5) in regime I. These chains represent the local patchiness of the charge distribution15 on the plastic surface. One observes multiple time scales in this spreading, e.g., the system initially spreads azimuthally within a few seconds. It then starts to arrange itself in the form of vertical chains, whose average length reaches the maximum value in about 10 s. For the next 100 s the chains spontaneously break and  . If one assumes that the length of the chain is proportional to the depth of the effective potential that stabilizes it, then its inverse square root dependence on time would result from the reduction in this depth due to diffusive dynamics of the countercharges on the substrate16.

. If one assumes that the length of the chain is proportional to the depth of the effective potential that stabilizes it, then its inverse square root dependence on time would result from the reduction in this depth due to diffusive dynamics of the countercharges on the substrate16.

Time evolution on stopping the drive.

(A) For  (Regime I), the initial state consists of particles concentrated in a high density region at one azimuthal position as in the first panel of A. In the final state long after the motion has stopped, the particles are uniformly spread over the entire surface with roughly the same inter-particle separations as in A last panel. The transition from the initial to the final configuration goes through an intermediate state where long chain like structures are favored. (C) shows the evolution of the average chain length with time t. For large values of t,

(Regime I), the initial state consists of particles concentrated in a high density region at one azimuthal position as in the first panel of A. In the final state long after the motion has stopped, the particles are uniformly spread over the entire surface with roughly the same inter-particle separations as in A last panel. The transition from the initial to the final configuration goes through an intermediate state where long chain like structures are favored. (C) shows the evolution of the average chain length with time t. For large values of t,  (shown by the dotted line). The data shown in A and C is for 500 μm glass particles in polystyrene vial. (B) For

(shown by the dotted line). The data shown in A and C is for 500 μm glass particles in polystyrene vial. (B) For  (Regime II), the particles stuck at lower height fall down and the density of stuck particles decreases and eventually becomes zero. This data is for d = 300 μm, f = 25 Hz and tw = 2.7 × 104 s in a PP vial. The change in the density of stuck particles as a function of time is shown in D for different values of tw (marked in the figure). In the inset of (D) we show the same variation for another system consisting of 500 μm particles. At large times we observe a power-law decay (shown by the solid lines), whose exponent, α, varies as a function of tw. (E) shows the variation of log(Ns(tw)/Ns(tw + t)), which is a measure of α, with tw for t = 10 s. The data shown in B, D and E is for 300 μm glass particles in polypropylene vial.

(Regime II), the particles stuck at lower height fall down and the density of stuck particles decreases and eventually becomes zero. This data is for d = 300 μm, f = 25 Hz and tw = 2.7 × 104 s in a PP vial. The change in the density of stuck particles as a function of time is shown in D for different values of tw (marked in the figure). In the inset of (D) we show the same variation for another system consisting of 500 μm particles. At large times we observe a power-law decay (shown by the solid lines), whose exponent, α, varies as a function of tw. (E) shows the variation of log(Ns(tw)/Ns(tw + t)), which is a measure of α, with tw for t = 10 s. The data shown in B, D and E is for 300 μm glass particles in polypropylene vial.

We now discuss the stability of the monolayer of particles stuck on the PP vial upon the cessation of driving. While the particles close to the top are well-adhered, the stability of those stuck at lower heights is found to depend on tw. Fig. 4B (Supplementary Movie: SM6) shows a typical time-lapsed sequence of images showing particles falling off the vial's surface after the orbital motion is turned off. The number density of the stuck particles decays in a manner shown in Fig. 4D. Here Ns(tw) is the number of stuck particles at the instant when the drive is switched off and t is the time measured since then. At long times, the decay can be approximated to Ns(tw + t) = Ns(tw)(t/τg)−α (Fig. 4D). A power-law decay typically implies the existence of multiple relaxation processes and a hierarchical structure of the potential energy landscape associated with the particle substrate interaction. Here, τg is the mean of the life time distribution of the stuck particles and the exponent α is a measure of its width. The variation of log(Ns(tw)/Ns(tw + t)) (which is a measure of α) with tw, is shown in Fig. 4E for t = 10 s. Within this scheme of analysis, α is nearly constant in regime I, while it varies substantially in regime II. The mean life time (τg) is very large in regime I and decreases with tw (Inset of Fig. 4D) in regime II. A visual inspection of the system, six months after the completion of the experiment, shows that the monolayer close to the top remains intact (Supplementary Information: Figure S4).

Single particle kinetics

For small values of tw the particles form a heap which moves with a velocity 2πRf as shown in Fig. 1A. A fraction of the particles get stuck to the surface of the vial with increasing time. In this section we analyse the motion of stuck particles under the influence of the periodic forcing due to the orbital motion. Typical time traces of the angular position (Δθ) of stuck particles at three different values of f (10, 12, 14 Hz) are shown in Fig. 5A. It exhibits an oscillatory behaviour with an asymmetric forward and reverse motion. The trajectory of the particle on the surface of the vial for one period of the orbital motion is shown in Fig. 5B (red line). The blue and green circles mark the position of the particle at the beginning and the end of the cycle, respectively. The initial configuration of the rest is marked by black dots. The angular shift between the blue and the green circles reflects its drift along the drive. The inset of Fig. 5A shows the probability distribution of the amplitude of the forward motion (θ0, marked in Fig. 5A) and the drift velocity (ν), calculated from the time traces of hundreds of stuck particles driven at f = 12 Hz The velocity distribution is particularly broad and highly asymmetric.

Single particle kinetics.

(A) Typical time traces of the angular position of stuck particles (d = 300 μm) at three different values of f measured at a given value of  . The two insets show the distribution in the amplitude of the forward motion, (θ0) and the drift velocity (v) obtained over hundreds of stuck particles at f = 12 Hz. (B) A typical trajectory of stuck particle (red line) during one complete cycle of orbital motion. The position of the particle at the beginning and the end of the cycle is marked by blue and green circles respectively. The black dots in the background show the positions of the rest of the particles at the beginning of the cycle. (C) Time trace of the angular position obtained using the model described in the text for f = 10 and 14 Hz and

. The two insets show the distribution in the amplitude of the forward motion, (θ0) and the drift velocity (v) obtained over hundreds of stuck particles at f = 12 Hz. (B) A typical trajectory of stuck particle (red line) during one complete cycle of orbital motion. The position of the particle at the beginning and the end of the cycle is marked by blue and green circles respectively. The black dots in the background show the positions of the rest of the particles at the beginning of the cycle. (C) Time trace of the angular position obtained using the model described in the text for f = 10 and 14 Hz and  . Variation of θ0 and v with f is shown in (D) and (E) respectively. (F) and (G) show the evolution of θ0 and v with tw, respectively, for

. Variation of θ0 and v with f is shown in (D) and (E) respectively. (F) and (G) show the evolution of θ0 and v with tw, respectively, for  . Typically v is observed to have a variance of the order of the mean values plotted and is not marked in the plots for clarity. (H)

. Typically v is observed to have a variance of the order of the mean values plotted and is not marked in the plots for clarity. (H)  and (I) tan (δ) as a function of f. In (H) the dash-dot line marks an i0 varying linearly with f, the behaviour seen in the control experiment described in Fig. 6C.

and (I) tan (δ) as a function of f. In (H) the dash-dot line marks an i0 varying linearly with f, the behaviour seen in the control experiment described in Fig. 6C.

The motion of a single particle under the periodic forcing is captured in a simple overdamped equation of motion:  where Γ is the measure of the frictional coupling. The term on the right hand side is the tangential component of the centrifugal force at the angular position (θ) of the particle on the vial. In general, this coupling depends on the stress history of the system17,18 and is typically viscoelastic19, hence Γ is a complex quantity ( = Γ′ + iΓ″)8. Microscopically the real part of Γ is related to the dissipative mechanisms in the system. This can arise due to inelastic inter-particle and substrate particle interactions. In the present scenario, the dissipation in the substrate-particle interactions is mainly due to the resistive loses associated with the ionic current in the vial. The momentum transferred from the sliding particles to the counter-charges produces this current. The spatial variation in the electrostatic potential between the particle and the substrate provides the elastic coupling of the particles to the local energy minima (pinning sites)8 and is related to the imaginary part of Γ. The variation of θ as a function of t is obtained by numerically solving the above equation. Since we observe that the particle moves over distances much larger than the typical interparticle separation (see Fig. 5B), we neglect the imaginary part of Γ in the numerical integration. In the

where Γ is the measure of the frictional coupling. The term on the right hand side is the tangential component of the centrifugal force at the angular position (θ) of the particle on the vial. In general, this coupling depends on the stress history of the system17,18 and is typically viscoelastic19, hence Γ is a complex quantity ( = Γ′ + iΓ″)8. Microscopically the real part of Γ is related to the dissipative mechanisms in the system. This can arise due to inelastic inter-particle and substrate particle interactions. In the present scenario, the dissipation in the substrate-particle interactions is mainly due to the resistive loses associated with the ionic current in the vial. The momentum transferred from the sliding particles to the counter-charges produces this current. The spatial variation in the electrostatic potential between the particle and the substrate provides the elastic coupling of the particles to the local energy minima (pinning sites)8 and is related to the imaginary part of Γ. The variation of θ as a function of t is obtained by numerically solving the above equation. Since we observe that the particle moves over distances much larger than the typical interparticle separation (see Fig. 5B), we neglect the imaginary part of Γ in the numerical integration. In the  , at long time, θ ~ 2πft, which is representative of the motion of the heap (Fig. 1A). For

, at long time, θ ~ 2πft, which is representative of the motion of the heap (Fig. 1A). For  , θ oscillates between two extremes that drift linearly with increasing time. Fig. 5C shows Δθ(t) for

, θ oscillates between two extremes that drift linearly with increasing time. Fig. 5C shows Δθ(t) for  and f = 10 Hz, 14 Hz. These time traces are similar to the ones obtained experimentally. Note, however, that it does not capture the inherent randomness observed in the jagged experimental time traces. A simple way to incorporate the randomness in an effective single particle equation of motion is through a spatially varying friction coefficient20,21, which is amply justified by the large distribution of single particle velocities measured in the experiment (see inset of Fig. 5 A). The frequency dependence of the mean amplitude of the forward motion (θ0) and the drift velocity of the extremas (ν) for the experimentally obtained traces is shown in Fig. 5D and E, respectively. The distribution in the drift velocity, ν, is particularly broad and its variance is of the order of the mean. A threshold behaviour, typical of friction dominated dynamics22, is particularly visible in the variation of ν with f. Frictional ageing in the system is reflected in the evolution of ν and θ0 with tw (for

and f = 10 Hz, 14 Hz. These time traces are similar to the ones obtained experimentally. Note, however, that it does not capture the inherent randomness observed in the jagged experimental time traces. A simple way to incorporate the randomness in an effective single particle equation of motion is through a spatially varying friction coefficient20,21, which is amply justified by the large distribution of single particle velocities measured in the experiment (see inset of Fig. 5 A). The frequency dependence of the mean amplitude of the forward motion (θ0) and the drift velocity of the extremas (ν) for the experimentally obtained traces is shown in Fig. 5D and E, respectively. The distribution in the drift velocity, ν, is particularly broad and its variance is of the order of the mean. A threshold behaviour, typical of friction dominated dynamics22, is particularly visible in the variation of ν with f. Frictional ageing in the system is reflected in the evolution of ν and θ0 with tw (for  ) as shown in Fig. 5 F and G, respectively.

) as shown in Fig. 5 F and G, respectively.

The local variation in the time evolution of the particle substrate frictional interaction aids the formation of the various growth patterns observed in the experiment. With time, the system spatially segregates into regions of high and low densities where particles have small and large mobilities, respectively. Futher, the frictional interactions evolve from being locally isotropic in regime I to being anisotropic in regime II. The former can be observed from the time averaged image shown in Fig. 3D first panel, while the latter is evident from the layered structure observed in the time averaged image in Fig. 3E first panel.

The real part of the frictional coupling (Γ) is related to the ionic diffusivity α in the system. This can be estimated from the growth of the particle front in the direction perpendicular to the mechanical drive. During the onset of regime II (Fig. 1) the front moves by a distance,  , in a time interval, δtw ~ 10 hours. From this we estimate a diffusion coefficient

, in a time interval, δtw ~ 10 hours. From this we estimate a diffusion coefficient  . The values of α is found to increase with f.

. The values of α is found to increase with f.

Electrical measurements

Along with imaging as described above, the charge developed in the system is simultaneously monitored by placing an electrode near the vial at a fixed location in the laboratory frame shown schematically in the insets of Fig. 6A. As discussed in Fig. 1, the centre of the vial moves in a circular orbit. At the closest point of approach, the electrode is s = 500 μm away from the vial's surface. The current induced in the electrode depends on the local (near the electrode) uncompensated charge on the vial, δQ and its velocity (u) with respect to the electrode, i.e., i = δQ.u.ϕ(r), where ϕ(r) is a proportionality constant whose value depends on the distance (r) between the electrode and the vial. In the present experimental geometry the distance between the centre of the vial and the electrode  and therefore the measured induced current (i) varies in an oscillatory manner; here A( = a + R + s) is the distance between the electrode and the centre of the orbit. A lock-in based phase sensitive technique has been used to measure the amplitude i0 and the phase (δ) of the current i. The phase is measured with respect to the vial's motion in the orbit. We use the trigger pulses generated by the position sensor (TCRT 5000) as the reference signal for the lock-in measurements.

and therefore the measured induced current (i) varies in an oscillatory manner; here A( = a + R + s) is the distance between the electrode and the centre of the orbit. A lock-in based phase sensitive technique has been used to measure the amplitude i0 and the phase (δ) of the current i. The phase is measured with respect to the vial's motion in the orbit. We use the trigger pulses generated by the position sensor (TCRT 5000) as the reference signal for the lock-in measurements.

In-situ electrical measurements.

The insets show the schematic side and plan view of the electrical measurement setup. In the plan view, the vial (marked by solid circle) moves on a circular orbit (dashed circle). The distances A and r mark the distance of the electrode from the centre of the orbit and the instantaneous position of the centre of the vial respectively. The distance of closest approach from the surface of the vial to the electrode is shown by s. Control experiment on the electrical measurement setup is performed by inserting a conducting tube inside the PP vial, which is connected to high voltage source. (A) and (B) show the measured amplitude and phase as a function of the voltage applied on the conducting tube. In this experiment, f = 20 Hz. The inset of (B) shows the variation of i0 and δ with the closest distance between the measuring electrode and the vial. (C) and (D) show i0 and δ as a function of f for two values of applied voltage V = 1 kVand −1 kV. The presence of a conducting tube to which a voltage is applied is specific to the control experiment. This is absent in the main experiments (described in Fig. 1). (E) and (F) show the simultaneously measured i0 and δ during the experiment described in Fig. 1. The dash dot line marks the position of  .

.

Control experiments

To determine the dependence of i0 and δ on the charge in the system, the frequency of the orbital motion (f) and the distance of closest approach (s) of the vial from the electrode, we perform the following control experiment. A conducting tube is inserted inside the vial so that it is in contact with it and a dc voltage (V) applied on the conducting tube. The charge on the conducting tube is proportional to the applied voltage. We find that the amplitude, i0, varies linearly with V (Fig. 6A) and frequency f (Fig. 6C) and it decreases with s (inset of Fig. 6B). The conducting tube has a self-capacitance of 20 pF and the slope of the linear fit between i0 and V provides a proportionality constant ~((10−12 Ccm−2 Hz)/nA). The phase (δ) is sensitive only to the sign of V (Fig. 6 B and D), is independent of the magnitude of f (Fig. 6D) and depends weakly on s (Fig. 6B inset).

In situ experimental results

The time evolution of i0 and tan(δ) for the experiment described in Fig. 1 is shown in Fig. 6E and F, respectively. This method does not measure the net charge on the particle or the substrate. Instead, it is sensitive to the charge imbalance (δQ) at a local scale, i.e. near the electrode. The phase is sensitive to the motion of the charges with respect to the surface of the vial. A typical measured i0 ~ 1 nA (Fig. 6E) corresponds to a net unbalanced charge of 10−12 Ccm−2 Hz. This provides a lower bound of 10−14 C of charge per particle (d = 300 μm). Alternatively, the average charge acquired by the glass particles in the experiment is measured by pouring the particles into a Faraday cup connected to a Keithley 6514 system electrometer. This method provides a value of charge per particle (d = 300 μm) to be equal to 10−13 C. Near the end of regime I, one observes a rise in i0 and a distinct cusp in tan(δ) at a time which precedes  . These precursor events lead to the onset of regime II.

. These precursor events lead to the onset of regime II.

The variation of  and tan (δ) with frequency for the experiment described in Fig. 5D and E is shown in Fig. 5 H and I. From the control experiments we expect

and tan (δ) with frequency for the experiment described in Fig. 5D and E is shown in Fig. 5 H and I. From the control experiments we expect  to have a constant value. The change in the slope of these curves coincides with the onset of drift of the particles (Fig. 5E). Similar variation in i0 and tan (δ) is observed at a given frequency as a function of time as the system crosses over from regime I to II (Fig. 6E and F), presumably related to the observed collective migration of particles (Fig. 1 C).

to have a constant value. The change in the slope of these curves coincides with the onset of drift of the particles (Fig. 5E). Similar variation in i0 and tan (δ) is observed at a given frequency as a function of time as the system crosses over from regime I to II (Fig. 6E and F), presumably related to the observed collective migration of particles (Fig. 1 C).

Conclusions

The present problem of an assembly of interacting particles being driven over a substrate is a particular realization of the more general problem of driven many body systems in a random potential which is commonly assumed to be time-invariant, i.e., quenched. In the present system the motion of the particles produces the triboelectric charging, thereby modifying the potential energy landscape over which the particles move. This, in turn, modifies the motion of the particles. This coupling between the spatial structure of the potential and the collective dynamics of the particles ensures that both evolve in a self-consistent manner, thereby producing novel self-assemblies that evolve in time. Time evolution of frictional coupling has been previously observed in a variety of systems, e.g., friction induced wear22, frictional ageing in rocks23, sticking of particles to substrates8. However, to our knowledge, the long-scale structural reorganization of the resulting potential energy landscape and their effects on the particle-assembly have been seldom investigated. We expect that the present set of observations will motivate further work on triboelectric phenomena as a rich source of pattern formation of particle assemblies moving over a time-evolving potential landscape.

Methods

Protocol for cleaning

To clean the soda-lime glass particles obtained from a local vendor, we heated them at 200°C for about an hour and then let them cool down to room temperature before starting the experiment. A soda-lime glass slide when treated in the same way shows that the contact angle made by a drop of water on it decreases significantly from 65° (Supplementary Information: Fig. S2 A left panel) to 14° (Supplementary Information: Fig. S2 A middle panel). When the contact angle measurement is repeated on the same slide after two days no significant deviation from 14° is observed (Supplementary Information: Fig. S2 A right panel). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) on the uncleaned glass particles shows a sharp dip in mass by 0.01% at T = 169°C (Supplementary Information Fig. S2 B (gray curve)). On repeating the TGA measurement on the same particles, the feature is not observed (Supplementary Information: Fig. S2 B blue curve). This implies that the volatile impurities have been removed from the surface by heating.

The polystyrene vials used in the experiment were obtained from Griener Bio One (Cat.-No.: 188171) and the polypropylene vials from Tarsons (Cat No- 523070, Lot No – B280312). The vials have been cleaned using dilute HCl solution. The vials are kept dipped in an aqueous solution of HCl (100 mM) for 10 hours, subsequent to which they are extensively rinsed using deionized water. The vials are then left in the oven at 60°C for about 12 hours to dry. We observe that the given protocol of cleaning makes the surface of the vial smooth (Supplementary Information: Fig. S2 C). Experiments have also been performed by increasing the time for which the vials are exposed to the acid by about 5 times (Supplementary Information: Table T1, Fig. S3).

Relative humidity

The humidity of the room where the experiments were carried out was maintained at ~55% using two dehumidifiers (White Westinghouse Dehumidifier – WDE201).

References

Ireland, P. M. Triboelectrification of particulate flows on surfaces: Part II — Mechanisms and models. Powder Technol. 198, 199–210 (2010).

Matsusaka, S., Maruyama, H., Matsuyama, T. & Ghadiri, M. Triboelectric charging of powders: A review. Chem. Eng. Sci. 65, 5781–5807 (2010).

Baytekin, H. T. et al. The Mosaic of Surface Charge in Contact Electrification. Science 333, 308–312 (2011).

Forward, K., Lacks, D. & Sankaran, R. Charge Segregation Depends on Particle Size in Triboelectrically Charged Granular Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 028001 (2009).

Grzybowski, B. A., Winkleman, A., Wiles, J. A., Brumer, Y. & Whitesides, G. M. Electrostatic self-assembly of macroscopic crystals using contact electrification. Nat. Mater. 2, 241–245 (2003).

Aranson, I. et al. Electrostatically Driven Granular Media: Phase Transitions and Coarsening. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3306–3309 (2000).

Nirmal Thyagu, N., Vasilenko, A., Voyiadjis, A., Glasser, B. J. & Shinbrot, T. Stuck in traffic: Patterns of powder adhesion. Eur. Phys. J. E 35, 105 (2012).

Kumar, D., Bhattacharya, S. & Ghosh, S. Weak adhesion at the mesoscale: particles at an interface. Soft Matter 9, 6618 (2013).

Ireland, P. M. Triboelectrification of particulate flows on surfaces: Part I — Experiments. Powder Technol. 198, 189–198 (2010).

Davies, D. K. Charge generation on dielectric surfaces. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2, 1533–1537 (1969).

Gu, Z., Wei, W., Su, J. & Yu, C. W. The role of water content in triboelectric charging of wind-blown sand. Sci. Rep. 3, 1337 (2013).

Burgo, T. A. L., Silva, C. A., Balestrin, L. B. S. & Galembeck, F. Friction coefficient dependence on electrostatic tribocharging. Sci. Rep. 3, 2384 (2013).

Reichhardt, C. & Nori, F. Phase Locking, Devil's Staircases, Farey Trees and Arnold Tongues in Driven Vortex Lattices with Periodic Pinning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 414–417 (1999).

Lettinga, M. & Grelet, E. Self-Diffusion of Rodlike Viruses through Smectic Layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 197802 (2007).

Glotzer, S. C. & Solomon, M. J. Anisotropy of building blocks and their assembly into complex structures. Nat. Mater. 6, 557–562 (2007).

Chaikin, P. M. & Lubensky, T. C. Principles of condensed matter physics. (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Dieterich, J. H. Time-dependent friction and the mechanics of stick-slip. Pure Appl. Geophys. 116, 790–806 (1978).

Ruina, A. Slip instability and state variable friction laws. J. Geophys. Res. 88, 10359 (1983).

Bahadur, S. & Ludema, K. C. The viscoelastic nature of the sliding friction of polyethylene, polypropylene and copolymers. Wear 18, 109–128 (1971).

Miguel, M. C., Rubí, J. M. & Sitges Conference. Jamming, yielding and irreversible deformation in condensed matter. (Springer, 2006).

Grüner, G. The dynamics of charge-density waves. Rev. Mod. Phys. 60, 1129–1181 (1988).

Persson, B. N. J. Sliding friction: physical principles and applications. (Springer, 2000).

Li, Q., Tullis, T. E., Goldsby, D. & Carpick, R. W. Frictional ageing from interfacial bonding and the origins of rate and state friction. Nature 480, 233–236 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K. and S.Ghosh conceived the experiments. D.K. and S.Ghosh carried out the experiments and data analysis with the help of A.S. and S.Gohil. D.K., S.Ghosh, P.B. and S.B. contributed to the discussion of the results and writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, D., Sane, A., Gohil, S. et al. Spreading of triboelectrically charged granular matter. Sci Rep 4, 5275 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05275

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05275

This article is cited by

-

Stress Wave Propagation in Two-dimensional Buckyball Lattice

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

– a superposed sum of the static images, Is(tw). This image captures the different realizations of the configurations of the stuck particles and therefore closely represents the energy landscape associated with the charge distribution on the surface of the vial. The summed image has no distinct structure barring for a hint of granularity in regime I (

– a superposed sum of the static images, Is(tw). This image captures the different realizations of the configurations of the stuck particles and therefore closely represents the energy landscape associated with the charge distribution on the surface of the vial. The summed image has no distinct structure barring for a hint of granularity in regime I ( . The superposed difference image (right panel of

. The superposed difference image (right panel of