Abstract

Fermentative hydrogen production from wastes has many advantages compared to various chemical methods. Methodology for characterizing the hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures is essential for monitoring reactor operation in fermentative hydrogen production, however there is lack of such kind of standardized methodologies. In the present study, a new index, i.e., the maximum specific hydrogen-producing activity (SHAm) of anaerobic mixed cultures, was proposed and consequently a reliable and simple method, named SHAm test, was developed to determine it. Furthermore, the influences of various parameters on the SHAm value determination of anaerobic mixed cultures were evaluated. Additionally, this SHAm assay was tested for different types of substrates and bacterial inocula. Our results demonstrate that this novel SHAm assay was a rapid, accurate and simple methodology for determining the hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures. Thus, application of this approach is beneficial to establishing a stable anaerobic hydrogen-producing system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy shortage is one of major global challenges and thus there is an increasing interest in the search for renewable energy sources to meet the current and future energy requirements1,2,3. Hydrogen is an attractive potential alternative energy source due to its advantages including clean, efficient and non-polluting characteristics4,5. Compared with various chemical methods for hydrogen production, biological hydrogen production by fermentative process can be operated at ambient temperatures and normal pressures6,7,8. Furthermore, this process can reuse a large amount of various waste materials from industries and agriculture9,10,11. Therefore, biological hydrogen production facilitates both waste treatment and energy recovery12.

During the start-up or steady-state operation of fermentative hydrogen-producing reactor, a sufficient quantity of active hydrogen-producing bacteria should be maintained within anaerobic reactors. Therefore, methodology for characterizing the hydrogen-producing bacteria and their activity is essential for monitoring reactors from the standpoint of the design and operation. Some techniques, such as microscopic counts, most probable number (MPN), adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and dehydrogenase activity, might be available to determine the level and activity of hydrogen-producing bacteria13,14. However, the use of the MPN test was found to be not practical due to long doubling times, requirements of strict anaerobic conditions and the difficulty in cultivating some of the species involved. Both ATP and dehydrogenase activity assays cannot be used as reliable methods for determining the level of active hydrogen-producing bacteria14. In order to find out the optimum initial pH, substrate concentration, inocula and enrichment procedure to start up a hydrogen-producing reactor, van Ginkelet al.15 adopted a modified Gompertz equation to simulate a batch hydrogen production process and determine the hydrogen production rate of anaerobic mixed cultures. In another study, Zheng et al.16 investigated the influence of illumination on the fermentative hydrogen production system and also used a modified Gompertz equation to calculate the specific hydrogen production rate of anaerobic mixed cultures. However, three model parameters - lag time, H2 production potential and H2 production rate, were adjusted to fit the experimental data in this empirical model. Even though this curve-fitting approach yields high correlation coefficients between the observed and fitted hydrogen evolution data, the three model parameters determined by curve-fitting were restricted to specific experimental conditions17. In a methane-producing reactor, the specific methanogenic activity (SMA) assay has been demonstrated to be an effective method and therefore has been standardized and widely used to determine the methanogenic ability of anaerobic mixed cultures under various conditions18,19. However, there is no standardized methodology for biological hydrogen-producing activity assay. Similar with the SMA assay, development of such a standardized methodology is essentially required and important for evaluating the hydrogen-producing ability of anaerobic mixed cultures under various conditions, especially for comparison purpose to arrive at conclusions.

Therefore, the present study aimed at developing and standardizing the biological assay for determining the ability of anaerobic mixed cultures to convert substrate to hydrogen. Based on the kinetic relationships between substrate, product and microorganism, a reliable and simple approach was proposed to determine the hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures in this study. This method gave a direct measurement of the maximum rate of hydrogen production per unit of microbial biomass per unit time, e.g., the maximum specific hydrogen-producing activity (SHAm) of anaerobic mixed cultures, thus, was named as the SHAm test. Furthermore, the influences of various parameters, such as pH, substrate concentration and temperature, on the SHAm determination were also evaluated. Additionally, this SHAm assay was tested for different types of substrates and bacterial sources and then verified with two case studies20,21. The use of such an SHAm test could allow us to rapidly, accurately and simply determine the potential hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures, which would be useful for establishing a stable anaerobic hydrogen-producing system.

Results

Definition of SHAm

The relationship between microbial growth and product formation for the anaerobic hydrogen production by mixed anaerobic cultures was simulated by the Luedeking-Piret model22:

where αi is growth-associated formation coefficient of product i; βi is non-growth-associated formation coefficient of product i (Pi); X is microorganism concentration (g-VSS/L); and VSS is volatile suspended solids.

Eq. (1) could be changed into:

where dPi/dt/X is specific formation rate of product i; and μ (1/d) is specific growth rate of microorganisms. A straight line could be obtained with an intercept of βi and a slope of αi, if plotting dPi/dt/X against μ.

In the anaerobic fermentative process, a typical fitted plot for hydrogen production by mixed anaerobic cultures was reported in Mu et al.22 and the estimated βH2 value was nearly equal to zero, suggesting that the formation of hydrogen in such a process was mainly growth-associated. Although hydrogen can be produced during stationary phase(s) of bacterial cultures, several studies have also suggested that hydrogen was mainly produced during the period of biomass growth compared to the stationary phase in batch test for anaerobic mixed cultures20,21,23,24,25,26, further suggesting that the formation of hydrogen was substantially (but not purely) growth-dependent in the anaerobic fermentative process by mixed cultures. As a consequence, the correlation between hydrogen and substrate could be expressed as Eq. (3)27:

where S (mmol/L) is substrate concentration; and YH2 (mL-H2/mmol-substrate) is hydrogen yield coefficient.

In a batch fermentative hydrogen production process, Eq. (3) could be changed into:

where VH2 (mL) is accumulated volume of hydrogen; VR (L) is reactor volume; T0 (K) is standard temperature, e.g., 273.15 K; and T1 (K) is room temperature.

The degradation of substrate was expressed by Monod-type equation:

where Umax (1/d) is maximum specific substrate degradation rate; and Ks (mmol/L) is half-saturation constant.

The following Eq. (6) was obtained by combining Eqs. (4) and (5):

At the beginning of fermentation, S≫Ks, thus Eq. (6) was simplified into:

Here, we defined the SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures (mL-H2/g-VSS/d) as:

Thus, Eq. (7) could be rewritten as:

Eq. (9) indicates that the specific hydrogen production rate of anaerobic mixed cultures was a constant value at the beginning of fermentation, which was equal to the SHAm.

The SHAm determination of anaerobic mixed cultures could be useful in a fermentative hydrogen production process. At the beginning of the start-up period of a new reactor, the activities of the seeding anaerobic mixed cultures and its amount are of great importance. During the phases after start-up, a regular determination of SHAm provides information about the change of the hydrogen-producing biomass, usually with a high level of inactive organic matter, until the consecution of biomass mostly composed by active bacteria. As a consequence, a simple method was developed to assess the SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures as follows.

Determination of SHAm

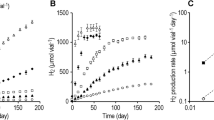

A typical curve of the accumulated hydrogen with fermentative time is shown in Figure 1(A). After a lag time, the volume of accumulated hydrogen increased with the increasing fermentative time and a linearity of hydrogen production with time would be observed at the beginning of fermentation according to Eq. (9). Consequently, the value of SHAm could be calculated from Eq. (10):

where k (mL-H2/h) is slope of the linearity of hydrogen production.

The CH4 formation was very limited for all of the SHAm tests due to the significant elimination of methanogens in the inocula by various pretreatments. As shown in Figure 1(B), the CH4 percentage was lower than 3% in the gas phase for the heat-pretreated inocula. In addition, the produced H2S could be completely removed in the washing flask with 5 mol/L NaOH solution. Therefore, it is expected that the formation of both CH4 and H2S should have no significant influence on the measurement of H2 volume with the liquid displacement method.

It is noteworthy that a higher volume of gas would be measured at initial fermentation, due to nitrogen gas in the fermentor. The fraction of nitrogen gas in the gas collector could be expressed as follows13:

where E is nitrogen percentage in the gas collector; Vg (mL) is volume of accumulated gas at fermentative time t (h); and Va (mL) is gas-space volume of fermentative reactor.

A small Ea value of 0.03 is able to be obtained when the ratio of Vg(t) and Va is 3.5, implying that the nitrogen in the fermentor had been almost removed. Therefore, in order to eliminate the influence of nitrogen gas, the initial point for SHAm calculation should be chosen when the accumulated gas is 3.5 times in volume of gas-space of fermentor, as indicated in Figure 1. The gas-space volume of the fermentative reactor was around 10 mL in this study.

Effects of various operational parameters on SHAm

As shown in Figure 2, the SHAm of the anaerobic mixed cultures increased from 419 ± 11 to 896 ± 8 mL-H2/g-VSS/d as pH was increased from 4.0 to 5.5, then decreased to 496 ± 38 mL-H2/g-VSS/d with a further increase to 7.0. A maximum SHAm value was obtained at pH 5.5. The microbial activities may be controlled by the overall enzymatic activity, which is pH dependent, as shown in the follows28:

where E represents the active enzyme and E+ and E−are the less active forms of charge-carrying enzyme. Assuming KH and KOH are the respective equilibrium constants of above two reactions, the SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures could be expressed as:

where OSHAm is the optimum SHAm (mL-H2/g-VSS/d). As shown in Figure 2, the relationship between SHAm and pH was well simulated by Eq. (12) with a high correlation coefficient of 0.930. The values of KH, KOH and OSHAm were determined as 9.0 × 10−5 mol/L, 1.1 × 10−7 mol/L and 905 mL-H2/g-VSS/d, respectively. The estimated maximum SHAm of 905 mL-H2/g-VSS/d was much close to the experimental maximum value of 896 ± 8 mL-H2/g-VSS/d, whereas the predicted optimum pH [(pKOH+ pKH)/2] was equal to the experimental optimum pH of 5.5. Additionally, the final pH was in a range of 4.5–4.0 due to the production of volatile fatty acids in the fermentative hydrogen production process.

The effect of substrate concentration on the SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures is presented in Figure 3. The SHAm increased from 555 ± 30 to 1400 ± 49 mL-H2/g-VSS/d with the increasing sucrose concentration from 2.92 to 17.54 mmol/L, then decreased to 1049 ± 50 mL-H2/g-VSS/d as the sucrose concentration was further increased to 20.47 mmol/L. The dependence of SHAm on the initial substrate concentration could be described using the generalized Haldane equation29:

and the non-competitive inhibition equation29:

where Ki (mmol/L) is inhibition constant; I (mmol/L) is inhibitor concentration; and n is a constant (order of inhibition).

In parameter estimation, n was given values of 1 (referred to as Eq. (13a)) and 2 (referred to as Eq. (13b)). The fitted curves by Eqs. (13a), (13b) and (14) are shown in Figure 3 and the estimated values of various parameters are listed in Table 1. Although all of equations gave a well description about the relationship between SHAm and substrate concentration, the Ks value, being higher than Ki estimated by both Eq. 13a and Eq. 13b, was not likely to be correct, on the basis of the values of Ks and Ki for methane production process found in literatures27,30. Therefore, the non-competitive equation, i.e., Eq. (14), might be more suitable for describing the relationship and the following estimates for OSHAm, Ks and Ki were selected as 4878 mL-H2/g-VSS/d, 22.77 mmol/L and 22.77 mmol/L, respectively. In literatures very limited information about the values of Ks and Ki for fermentative hydrogen production processes is available. Although in general the value of Ki should be much higher than the Ks value, a previous study also reported that the value of Ki was close or even equal to the Ks value in biological methane production29. The reasons behind such an inconsistence need further investigations.

The effect of temperature on the SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures was investigated in a range of 20.0 to 55.0°C, as presented in Figure 4. An increase in SHAm of anaerobic mixed cultures was observed from 864 ± 80 to 6400 ± 160 mL-H2/g-VSS/d with the increase in temperature. The temperature dependence of anaerobic mixed cultures SHAm was described by an Arrhenius type equation with a high correlation coefficient value of 0.986:

where K (mL-H2/g-VSS/d) is frequency factor; Ea (kJ/mol) is apparent activation energy; R (0.008314 kJ/mol/K) is gas constant; and T (K) is absolute temperature. As shown in Figure 4, the values of K and Ea were respectively estimated as 7.0 × 1010 mL-H2/g-VSS/d and 44.2 kJ/mol.

Comparison of SHAm for different substrates and bacterial sources

As shown in Table 2, the SHAm values of anaerobic mixed culture were similar for different types of substrates and in a range of 900–1000 mL-H2/g-VSS/d. This might be due to that all of substrates used were soluble and their hydrolysis was not a rate-limiting step for these substrates31.

The SHAm values had a notable difference for various bacterial sources, as summarized in Table 3. The anaerobic microflora from the upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor had a highest SHAm value of 1632 ± 288 mL-H2/g-VSS/d, while a lowest value of 935 ± 12 mL-H2/g-VSS/d for the anaerobically digested sludge from the municipal wastewater treatment plant. This result suggests that the method developed in this study could be applicable to assess the specific hydrogen-producing ability of different mixed bacterial inocula.

Application for two case studies

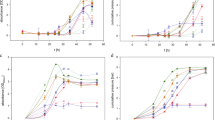

The methodology developed in this study was applied to describe the results reported in two cases20,21. Different factors were intensively examined for their effects on the H2-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures in Case 120. As shown in Figure 5(A), the relationship between the microbial growth and the product formation in their study was also well simulated by the Luedeking-Piret model with a regression coefficient higher than 0.8. Moreover, the estimated βH2 value was equal to zero, suggesting that the formation of hydrogen in such a process was mainly growth-dependent. Consequently, the SHAm values of the anaerobic mixed culture were estimated using Eq. (10) and the results at various pH values are shown in Figure 5(B). A maximum SHAm value was observed at pH 6.0 for the anaerobic mixed cultures in their study. The estimated βH2 value was also equal to zero in Case 2 (Figure 6A), where the activated sludge was adopted as the seed for hydrogen production21, further suggesting that hydrogen production using mixed cultures was mainly growth-dependent. Additionally, the calculated SHAm value was about 186 mL-H2/g-VSS/d in Case 2 (Figure 6B).

(A) Luedeking-Piret model plot for the relationship between the hydrogen formation rate and the specific growth rate of microorganisms and (B) the estimated SHAm values of the anaerobic mixed cultures at various pHs from Case 120.

(A) Luedeking-Piret model plot for the relationship between the hydrogenformation rate and the specific growth rate of microorganisms and (B) the estimated SHAm value of the anaerobic mixed cultures from Case 221.

Discussion

Biological hydrogen fermentation is a microbial process, which requires careful design and control. In practice, the process design is usually based on sludge loading rate and VSS is usually used to characterize the concentration of hydrogen-producing sludge. However, the VSS is undefined as it includes active biomass, as well as dead cell and particulate organic matter. The SHAm test proposed in this study is able to accurately quantify the hydrogen-producing activity of sludge in a simple and quick way under different conditions. Thus, the SHAm of sludge is likely to be more useful than VSS as a parameter for the design and operation of anaerobic hydrogen-producing reactors.

Hydrogen partial pressure in the liquid phase is one of the key factors affecting hydrogen production32. Tanisho et al.33 observed an increase in residual NADH by sparging with argon in the reactor, which expected to give an increased hydrogen production. Logan et al.31 measured hydrogen production in two types of batch tests (Owen and respirometer) and found that the respirometric method resulted in the production of 43% more hydrogen from glucose than the Owen method. Therefore, a continuous gas release method (similar to respirometric one) was adopted in the SHAm test, in order to reduce the influence of hydrogen partial pressure on hydrogen production in reactors.

Hydrogen production with anaerobic mixed cultures has been shown to be affected by many factors, such as pH, substrate concentration and temperature34,35,36. If we want to measure the real potential hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures, the optimum conditions should be provided in the SHAm test. Many studies have demonstrated that proper control of pH is crucial to the hydrogen production and the reported optimum pH value is in a wide range of pH 5.0 to pH 9.0 for different types of hydrogen-producing cultures37,38,39,40. This implies that the optimum pH for the SHAm was likely different for various bacteria, although a peak value of SHAm was observed at pH 5.5 for the anaerobic mixed cultures used in this study.

The substrate concentration is also critical in the microenvironment of the hydrogen-producing bacteria. A high substrate concentration could ensure a more rapid diffusion of substrate into microorganisms. However, as shown in Figure 3, when the substrate concentration was higher than 5.6 g-COD (chemical oxygen demand)/L, the SHAm value of anaerobic mixed cultures in this study was reduced, which could be attributed to the possible inhibition caused by substrate and its products. On the other hand, the main purpose of this assay is to describe the hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures. It is thus important to avoid the great changes of anaerobic mixed cultures in characteristics during the assay itself. Of particular importance is the possibility that the hydrogen-producing bacteria population significantly increases during the course of the assay. Figure 7(A) shows that the relative increase in the hydrogen-producing biomass concentration (RIHP) was increased from 6.7 ± 1.0% to 47 ± 7% with an increase in substrate concentration from 1.1 to 7.8 g-COD/L in the SHAm tests. However, when the RIHP value was higher than 32% (i.e., substrate concentration of 5.6 g-COD/L), the SHAm values started to decrease in the tests, as shown in Figure 7(B). Such a decrease could be attributed to the fact that the diffusion of substrate to bacteria might become a rate-limiting step if the biomass concentration was too high in the SHAm tests. Therefore, the substrate concentration should be carefully selected based on two major reasons above and a much higher substrate concentration (e.g., more than 5.6 g-COD/L in this study) should not be applied in the SHAm tests.

An increasing SHAm was found with the increasing temperature, however, the temperature was a fixed condition for a given anaerobic hydrogen production system. In other words, it may not always be economical to heat or cool wastewater. It is obvious that if the tests were conducted at a lower or higher temperature than that of reactor system you are considering, the SHAm measured would be either lower or higher than the real value.

It should be kept in mind that this SHAm test is aimed at measuring the capacity of anaerobic mixed cultures to convert substrate to hydrogen only. In anaerobic methane production, the SMA test could be used to estimate the substrate-degrading ability of microorganisms because the end products are methane and carbon dioxide only40,41. However, in addition to hydrogen, volatile fatty acids and alcohols are also produced in fermentative hydrogen production. Therefore, this SHAm assay cannot be adopted to determine the substrate-degrading ability of hydrogen-producing microorganisms. Additionally, soluble substrates are usually recommended to be used in the SHAm assay as it is difficult to estimate biomass concentration when using complex heterogeneous substrate such as lignocellulosic biomass and starchy wastewater in experiment. However, if using insoluble matter as substrate in the test, the SHAm method should be further improved and could couple with other methodologies of molecular biology to accurately determine the microbial biomass concentration.

In addition to for determining the hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures, the SHAm assay developed in this study could also be used for optimizing the operational conditions of hydrogen production reactors. Furthermore, this standardized methodology might be able to monitor any deterioration in the performance of reactors under variable operating conditions, such as toxicity of various heavy metals in wastewaters42.

Methods

Hydrogen-producing mixed cultures and substrate

In this study five different bacterial sources were respectively taken as inocula, including (1) anaerobic microflora from a full-scale UASB reactor treating soybean-processing wastewater located in Benpu City, China; (2) anaerobically digested sludge from Zhuzhuanjing Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant in Hefei City, China; (3) anaerobic sludge from a 600-m3 CSTR (continuous stirred tank reactor) treating chicken manure located in Jieshou City, China; (4) cow dung compost from a farm in Benpu City, China; and (5) sediments from Chaohu Lake, China. Prior to use, these inocula were sieved to remove stone, sand and other coarse matters. Thereafter, the inocula were heated at 102°C for 90 min to inactivate the methanogens and to enrich the hydrogen-producing bacteria31. The initial concentration of biomass in the fermentor was about 3 g-VSS/L for all experiments.

On the other hand, various types of substrates, including glucose, sucrose, starch and brewage wastewater, were also compared in this study. Except for the brewage wastewater, all of other substrates were supplemented with buffering chemicals and balanced nutrients as follows (unit in mg/L): NH4HCO3 405; K2HPO4·3H2O 155; CaCl2 50; MgCl2·6H2O 100; FeCl2 25; NaCl 10; CoCl2·6H2O 5; MnCl2·4H2O 5; AlCl3 2.5; (NH4)6Mo7O24 15; H3BO4 5; NiCl2·6H2O 5; CuCl2·5H2O 5; ZnCl2 5. The characteristics of the brewage wastewater were similar to those reported by Yu et al43. The initial substrate concentration was about 3.4 g-COD/L for all experiments except for the tests with various substrate concentrations, where the amounts of all organic and inorganic constituents were adjusted pro rata.

Test procedures of SHAm

Using a continuous gas release apparatus, the setup of the SHAm test consisted of a 300-mL fermentor (serum vial), washing flask, gas collector, graduated flask and vibrator with constant temperature. A required amount of anaerobic mixed cultures and substrate were respectively added into the serum vial and the working volume was adjusted to 290 mL with distilled water. The required initial solution pH was adjusted using either 5 mol/L HCl or KOH. Then, the vials were flushed with nitrogen gas to remove oxygen from the solution and were immediately capped with a rubber septum stopper and tied down with plastic fasteners. The vials were kept in incubator shaker at 180 rpm. The gas produced passed through carbon dioxide scrubber (5 mol/L NaOH solution) and was thus collected using water displacement method.

Analysis

Sucrose concentration was determined by using anthrone-sulfuric acid method44, while COD and VSS were measured using the standard methods45. The percentage of H2, N2 and CH4 in the gas was analyzed by using a GC (Model SP-6800A, Lunan Co., China) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector and a 3 m stainless column packed with 5 Å molecular sieve. The operational temperatures at the injection port, the column oven and detector were 70, 80 and 80°C, respectively.

In anaerobic fermentative hydrogen production process, the RIHP was defined as:

where X0 (g-VSS/L) is initial hydrogen-producing biomass concentration; and X (g-VSS/L) is hydrogen-producing biomass concentration at fermentative time t (h).

References

Young, S. Tomorrow's energy: Hydrogen, fuel cells and the prospects for a cleaner planet. Nature 414, 6863 (2001).

Gelfand, I. et al. Sustainable bioenergy production from marginal lands in the US Midwest. Nature 493, 514 (2013).

Logan, B. E. & Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 488, 313–319 (2012).

Maeda, K. et al. Photocatalyst releasing hydrogen from water - Enhancing catalytic performance holds promise for hydrogen production by water splitting in sunlight. Nature 440, 295 (2006).

Turner, J. A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 305, 972–974 (2004).

Lee, H. S., Vermaas, W. F. J. & Rittmann, B. E. Biological hydrogen production: prospects and challenges. Trends in Biotechnol. 28, 262–271 (2010).

Choi, J. A. et al. Enhancement of fermentative bioenergy (ethanol/hydrogen) production using ultrasonication of ScenedesmusobliquusYSW15 cultivated in swine wastewater effluent. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3513–3520 (2011).

Adams, M. W. W. & Stiefel, E. I. Biochemistry - Biological hydrogen production: Not so elementary. Science 282, 1842–1843 (1998).

Lin, C. Y. et al. Fermentative hydrogen production from wastewaters: A review and prognosis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 37, 15632–15642 (2012).

Pant, D. & Adholeya, A. Biological approaches for treatment of distillery wastewater: A review. Bioresource Technol. 98, 2321–2334 (2007).

Yang, S. S. et al. Simultaneous waste activated sludge disintegration and biological hydrogen production using an ozone/ultrasound pretreatment. Bioresource Technol. 124, 347–354 (2012).

Ren, N. Q. et al. Biological hydrogen production by dark fermentation: challenges and prospects towards scaled-up production. Curr. Opin. Biote. 22, 365–370 (2011).

Dolfing, J. & Bloemen, W. G. B. M. Activity measurements as a tool to characterize the microbial composition of the methanogenic environments. J. Microbiol. Methods. 4, 1–12 (1985).

Ince, O., Ince, B. K. & Yenigun, O. Determination of potential methane production capacity of a granular sludge from a pilot-scale upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor using a specific methanogenic activity test. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 76, 573–578 (2001).

Van Ginkel, S., Sung, S. & Lay, J. J. Biohydrogen production as a function of pH and substrate concentration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 4726–4730 (2001).

Zheng, G. C. et al. Effect of illumination on the hydrogen-production capability of anaerobic activated sludge. Front. Env. Sci. Eng. 6, 125–130 (2012).

Gadhamshetty, V., Arudchelvam, Y., Nirmalakhandan, N. & Johnson, D. C. Modeling dark fermentation for biohydrogen production: ADM1-based model vs. Gompertz model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 35, 479–490 (2010).

Angelidaki, I. & Schmidt, J. E. Activity test for the three reactors in green farm energy (Technical University of Denmark, Denmark, 2002).

Siggins, A., Enright, A. M. & O'Flaherty, V. Low-temperature (7°C) anaerobic treatment of a trichloroethylene-contaminated wastewater: Microbial community development. Water Res. 45, 4035–4046 (2011).

Lee, K. S. et al. Exploring optimal environmental factors for fermentative hydrogen production from starch using mixed anaerobic microflora. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 33, 1565–1572 (2008).

Xue, C. H. Biological hydrogen production from wastewater using activated sludge and its kinetics (Kunming University of Science and Technology, China, 2008).

Mu, Y., Wang, G. & Yu, H. Q. Kinetic modeling of batch hydrogen production process by mixed anaerobic cultures. Bioresource Technol. 97, 1302–1307 (2006).

Chen, C. C., Lin, C. Y. & Chang, J. S. Kinetics of hydrogen production with continuous anaerobic cultures utilizing sucrose as the limiting substrate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57, 56–64 (2001).

Lo, Y. C. et al. Dark H2 fermentation from sucrose and xylose using H2-producing indigenous bacteria: Feasibility and kinetic studies. Water Res. 42, 827–842 (2008).

Fernández, F. J., Villaseńor, J. & Infantes, D. Kinetic and stoichiometric modelling of acidogenic fermentation of glucose and fructose. Biomass Bioenerg. 35, 3877–3883 (2011).

Yuan, X. Z. et al. Anaerobic biohydrogen production from wheat stalk by mixed microflora: Kinetic model and particle size influence. Bioresource Technol. 102, 9007–9012 (2011).

Yang, S. T., Tang, I. C. & Okos, M. R. Kinetics and mathematical modeling of homoacetic fermentation of lactate by Clostridium formicoaceticum. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 32, 797–802 (1988).

Yu, H. Q. & Fang, H. H. P. Acidogenesis of gelatin-rich wastewater in an upflow anaerobic reactor: influence of pH and temperature. Water Res. 37, 55–66 (2003).

Kettunen, R. H. & Rintala, J. A. The effect of low temperature (5-29°C) and adaptation on the methanogenic activity of biomass. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48, 570–576 (1997).

Fukuzaki, S., Nishio, N. & Nagai, S. Kinetics of the methanogenic fermentation of acetate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 3158–3163 (1990).

Logan, B. E., Oh, S. E., Kim, I. S. & van Ginkel, S. Biological hydrogen production measured in batch anaerobic respirometers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 2530–2535 (2002).

Park, W. et al. Removal of headspace CO2 increases biological hydrogen production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 4416–4420 (2005).

Tanisho, S., Kuromoto, M. & Kadokura, N. Effect of CO2 removal on hydrogen production by fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 23, 559–563 (1998).

Oh, S. E., Lyer, P., Bruns, M. A. & Logan, B. E. Biological hydrogen production using a membrane bioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87, 119–27 (2004).

Ueno, Y., Fukui, H. & Goto, M. Operation of a two-stage fermentation process producing hydrogen and methane from organic waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 1413–1419 (2007).

Chu, C. Y., Wu, S. Y., Tsai, C. Y. & Lin, C. Y. Kinetics of cotton cellulose hydrolysis using concentrated acid and fermentative hydrogen production from hydrolysate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 36, 8743–8750 (2011).

Mu, Y., Zheng, X. J. & Yu, H. Q. Determining optimum conditions for hydrogen production from glucose by an anaerobic culture using response surface methodology (RSM). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 34, 7959–7963 (2009).

Song, J. X. et al. Effects of pH and ORP on microbial ecology and kinetics for hydrogen production in continuously dark fermentation. Bioresource Technol. 102, 10875–10880 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Acidogenic fermentation of proteinaceous sewage sludge: Effect of pH. Water Res. 46, 799–807 (2012).

Yuan, X. Z. et al. Biogas production and microcystin biodegradation in anaerobic digestion of blue algae. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1511–1515 (2011).

Boe, K., Karakashev, D., Trably, E. & Angelidaki, I. Effect of post-digestion temperature on serial CSTR biogas reactor performance. Water Res. 43, 669–676 (2006).

Li, C. L. & Fang, H. H. P. Inhibition of heavy metals on fermentative hydrogen production by granular sludge. Chemosphere. 67, 668–673 (2007).

Yu, H. Q., Zhu, Z. H., Hu, W. R. & Zhang, H. S. Hydrogen production from rice winery wastewater in an upflow anaerobic reactor by using mixed anaerobic cultures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 27, 1359–1365 (2002).

Dubois, M. et al. Colorimetric method for determination sugars and related substance. Anal. Chem. 28, 350–356 (1956).

APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater 20th (American Public Health Association, Washington DC, 1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Natural Science Foundation of China (51222812), the Recruitment Program of Global Experts and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of the Ministry of Education of China for the financial support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. carried out the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; H.Y.Y., Y.Z.W., C.S.H. carried out the experiments; Q.B.Z. and Y.W. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; H.Q.Y. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, Y., Yang, HY., Wang, YZ. et al. The maximum specific hydrogen-producing activity of anaerobic mixed cultures: definition and determination. Sci Rep 4, 5239 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05239

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05239

This article is cited by

-

Effect of volatile fatty acids mixtures on the simultaneous photofermentative production of hydrogen and polyhydroxybutyrate

Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.