Abstract

Charged platelet suspensions, such as swelling clays, disc-like mineral crystallites or exfoliated nanosheets are ubiquitous in nature. Their phase behaviours are nevertheless still poorly understood: while some clay suspensions form arrested states at low densities, others exhibit an equilibrium isotropic-nematic transition at moderate densities. These observations raise fundamental questions about the influence of electrostatic interactions on the isotropic-nematic transition and the organisation of charged platelets. We investigate the competition between anisotropic excluded-volume and repulsive electrostatic interactions in suspensions of charged colloidal discs, by means of Monte-Carlo simulations and characterization of the dynamics of the structures. We show that the original intrinsic anisotropy of the electrostatic potential between charged platelets not only rationalizes generic features of the complex phase diagram of charged colloidal platelets such as Gibbsite and Beidellite clays, but also predicts the existence of novel structures. Furthermore, we find evidences of a strong slowing down of the dynamics upon increasing density.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent breakthroughs in the synthesis of particles with precisely controlled shapes and interactions have sparked a renewed interest in understanding the influence of particle anisotropy on phase behavior1,2, which is required to achieve well-controlled self-assembly and design of novel structures. In the simplest case of axially symmetric particles, anisotropic excluded-volume interactions lead to formation of liquid-crystalline phases3 while more complex shapes result in remarkable structural diversity2. Directional interactions between particles, induced by their geometry and chemical structure, can also lead to anisotropic complex self-assembled structures.

When both particle geometry and interactions are anisotropic, the interplay and even competition between the excluded-volume and other (e.g. electrostatic, van der Waals) interactions may lead to the emergence of novel structures and geometrical frustration. Charged platelet suspensions, such as clays4,5,6,7, disc-like mineral crystallites8,9 or exfoliated nanosheets10,11, that have been widely studied experimentally provide such examples and are the subject matter of this report. All these systems are highly charged discotic colloids. Some of them, like Laponite and Bentonite clay suspensions4,5, form arrested states with increasingly slow dynamics at low densities. Others, like Beidellite and Gibbsite6,8, exhibit an equilibrium isotropic-nematic transition at moderate densities.

These observations urge us to understand the influence of interparticle interactions, specifically electrostatic interactions, on the organization of charged platelets. Here, we aim at disentangling the generic effects due to shape and charge, from more specific ones such as attractive interactions12,13 that depend on details of chemical constitution of each platelet system. We consequently focus on the role of repulsive electrostatic interactions on the phase behavior, although the attractive interactions turn out to be important for formation of gel-like arrested states in some systems like Laponite clays at low densities13,14.

For hard-core repulsions only, upon increasing platelet density, a sequence of isotropic, nematic, columnar and crystalline phases appears, depending on the aspect ratio15,16. Despite several simulation works17,18,19,20,21, the influence of electrostatic interactions on phase behavior is still poorly understood and a comprehensive study that provides an overview and rationalization of the experimental data is missing. Previous studies suffer from not taking into account the renormalised effective charge and the full orientational dependence of interactions17,21. Furthermore, most of them are based on coarse-grained interaction site models18,19,20, which are computationally costly.

Here, such shortcomings are circumvented: our approach is based on a well controlled effective electrostatic potential between two discs obtained within Poisson-Boltzmann formalism22,23. We address two important questions: i) how do repulsive electrostatic interactions, in conjunction with hard core, influence the isotropic-nematic (I/N) transition? ii) how do these interactions affect the translational and rotational dynamics of charged discs upon varying density or ionic strength and can they lead to a slow dynamics?

Results

The far-field dimensionless electrostatic interaction potential between two charged discs of diameter σ immersed in an electrolyte medium with ionic strength I = κ2/(8πλB), centers at a distance r apart and with normals making angles θi with the center-to-center line, reads22:

Here, κ is the inverse Debye length,  is the Bjerrum length (7.1 Å in water at room temperature) and Zeff is the effective charge; it depends on the platelet bare charge and salt through κσ. For highly charged platelets as considered here, Zeff saturates to a value

is the Bjerrum length (7.1 Å in water at room temperature) and Zeff is the effective charge; it depends on the platelet bare charge and salt through κσ. For highly charged platelets as considered here, Zeff saturates to a value  . The anisotropy function f(κσ, θ) encodes the orientational dependence of the potential and can be expressed as a sum of spheroidal wave functions, as discussed in detail in reference23. We have plotted f(κσ, θ) for several values of κσ in Fig. 1a. f(κσ, θ) increases with angle θ, reaching a maximum in the disc plane (θ = π/2). It is furthermore enhanced by the ionic strength (∝ κ2): a smaller Debye length (1/κ) acts as a probe which reveals asphericity. This results in a strong asymmetry between coplanar and stacked configurations (Fig. 1b), a notable difference with standard Heisenberg-like models. A competition between the excluded volume and electrostatic effects ensues, which is a generic feature for charged oblate spheroids. The interplay between anisotropy in shape and interactions has important consequences on the phase behaviour and dynamics.

. The anisotropy function f(κσ, θ) encodes the orientational dependence of the potential and can be expressed as a sum of spheroidal wave functions, as discussed in detail in reference23. We have plotted f(κσ, θ) for several values of κσ in Fig. 1a. f(κσ, θ) increases with angle θ, reaching a maximum in the disc plane (θ = π/2). It is furthermore enhanced by the ionic strength (∝ κ2): a smaller Debye length (1/κ) acts as a probe which reveals asphericity. This results in a strong asymmetry between coplanar and stacked configurations (Fig. 1b), a notable difference with standard Heisenberg-like models. A competition between the excluded volume and electrostatic effects ensues, which is a generic feature for charged oblate spheroids. The interplay between anisotropy in shape and interactions has important consequences on the phase behaviour and dynamics.

(a) Anisotropy function f(κσ, θ) versus θ, the angle between the disc normal  and the line of observation, for several values of κσ (b) Two interacting parallel charged discs in stacked and coplanar configurations with equal center to center distance correspond to minimum and maximum repulsion, respectively.

and the line of observation, for several values of κσ (b) Two interacting parallel charged discs in stacked and coplanar configurations with equal center to center distance correspond to minimum and maximum repulsion, respectively.

We have investigated the structure of hard discs interacting by the anisotropic Yukawa potential of Eq. (1) by NVT Metropolis Monte-Carlo simulations24 which generate states according to appropriate Boltzmann weights, using a procedure similar to simulated annealing (see the Methods Section). Hence, we identified the different phase regions in density-charge space from their structural behavior and orientational order parameter. This approach yields an overall picture of the phase diagram based on derived anisotropic effective interactions for charged platelets. Here, an important methodological point is in order. Precise locations of the phase boundaries and coexistence regions could in principle be derived from free energy calculations. However, use of the effective interaction potential Eq. (1) where microionic degrees of freedom have been integrated out, would not lead to the correct free energy. The reason for this is that in addition to the free energy resulting from colloid-colloid interactions, one should also account for the contribution of colloid-microions interactions and micro-ion entropy25,26. This contribution is unknown for discs where charge renormalization effects are important. As a consequence, should the free energy be required, one needs to explicitly account for micro-ions. Such simulations become formidably heavy with salt and under large charge asymmetry between the colloids and microions. Given that the free energy of the system is not fully accounted by Eq. (1) it would be senseless to pursue a rigorous calculation of the equilibrium phase diagram for this interaction potential. Yet, it is worth using pair potential Eq. (1) to find possible equilibrium and out-of-equilibrium structures by means of NVT Monte Carlo simulations. We can thus chart out the platelets phase behaviour from the Monte Carlo observed structural information. In doing so, we are not able to precisely locate the phase boundaries, nor coexistence regions.

The degree of orientational order was characterized by the nematic order parameter S ≡ 〈P2(cos(ψ)〉 where the second Legendre polynomial reads P2(x) = (3 cos2 x − 1)/2, ψ is the angle of a platelet normal with the director  and the brackets mean averaging over all particles. Hence, −1/2 < S < 1 with S = 0 for the disordered isotropic phase. When 0 < S < 1, the platelet normals point on average along the director

and the brackets mean averaging over all particles. Hence, −1/2 < S < 1 with S = 0 for the disordered isotropic phase. When 0 < S < 1, the platelet normals point on average along the director  while in the more unconventional S < 0 regime, the platelet normals are on average perpendicular to

while in the more unconventional S < 0 regime, the platelet normals are on average perpendicular to  (“antinematic” order).

(“antinematic” order).

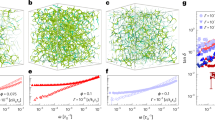

Upon varying density and ionic strength (proportional to (κσ)2), we found eight distinct structures (Fig. 2). Four of them have a vanishing S and are formed at low and moderate densities. Three of these structures, isotropic fluid, plastic crystal (structure with positional order but no orientational order) and “random stacks”, are orientationally disordered while the fourth one is a novel structure that consists of intertwined nematic and anti-nematic layers (Fig. 2). We coin it “nematic-antinematic intergrowth texture”. The orientationally ordered phases with S > 0.4 which appear at higher densities include two liquid-crystalline phases, i.e. nematic phase of platelet stacks (sometimes called “columnar nematic”) and hexagonal columnar phase, together with two crystalline phases with bcc-like and hexagonal symmetry.

We recognize eight distinct configurations for charged discs, four of which have a vanishing orientational order parameter S.

These include isotropic fluid, plastic crystal, “random stacks” and a novel “intergrowth texture” that is composed of discs arranged in alternating nematic (red colour) and antinematic (blue color) layers. The orientationally ordered structures with S > 0.4 encompass nematic and columnar hexagonal liquid-crystals in addition to two crystalline phases with bcc and hexagonal symmetry. Note that the discs are not displayed with their real size, but with 20 to 40% of their actual diameter.

Before turning to a comparison with experiments, we present the phase diagram. We emphasize that our gradual equilibration procedure for ρ* = ρσ3 ≥ 3 allows us to attain configurations close to equilibrium. On the other hand, in experimental situations starting from an initial configuration of random positions for particles at high concentrations, it might take a rather long time, up to years, to reach equilibrium. This is the case of Gibbsite suspensions8.

We now highlight important aspects of the phase diagram (Fig. 3) in connection with the features of our pair potential. A significant hallmark is the non-monotonic behavior of orientational disorder-order transition with κσ which results from the opposing effects of the decreasing potential range and the increasing amplitude of the anisotropy function, upon increasing ionic strength;  also increases but we verified that the observed trend is unchanged provided ZeffλB/σ > 2.3. This in turn implies that the particular value of σ/λB, which is a priori a relevant dimensionless parameter, in practice plays little role. This opens the possibility to discuss the results pertaining to different particle sizes solely in terms of ρ* and κσ, as will be done below.

also increases but we verified that the observed trend is unchanged provided ZeffλB/σ > 2.3. This in turn implies that the particular value of σ/λB, which is a priori a relevant dimensionless parameter, in practice plays little role. This opens the possibility to discuss the results pertaining to different particle sizes solely in terms of ρ* and κσ, as will be done below.

Phase diagram of repulsive charged discs as a function of dimensionless density ρ* and κσ which is proportional to square root of ionic strength.

The vertical dashed line at ρ* = 4.2 shows the density beyond which the nematic phase for hard discs (thus without electrostatic interactions) appears. The solid line separates the orientationally ordered (right hand side) and disordered phases (left hand side). The oblique dashed line is a guide to the eyes to show, on the right hand side, the regions where the structures with slow orientational dynamics appear.

In the limit of low ionic strengths corresponding to κσ = 1, where the potential is rather isotropic and long-ranged, bcc-like structures are formed, as observed with charged spheres at low κσ27. At low densities, discs are orientationally disordered (plastic crystal) and are reminiscent of the Wigner crystals observed for low volume fractions of charged spheres28. Increasing the ionic strength, at κσ = 2 where the amplitude of the anisotropy function is less than 1.2, the plastic crystal is replaced by an isotropic fluid at low and moderate densities. The crystal disappearance for a slightly larger κσ and shorter range of potential highlights the geometrical frustration effect of anisotropy. Performing simulations for a system of hard disks interacting with an isotropic Yukawa potential at the same value of Zeff and κσ, we verified that the observed geometrical frustration is indeed due to anisotropic nature of potential which leads to melting of crystalline structures at moderate densities. The details of this study will be published elsewhere.

At κσ = 2, in the high density regime, the long-range positional order is still preserved as crystals with hexagonal symmetry appear. Interestingly, for large enough ionic strengths leading to 4 ≤ κσ ≤ 6 and at moderate densities, the new intergrowth texture appears and, for κσ ≥ 8, randomly oriented stacks of discs are observed. The intergrowth texture consists of sets of aligned discs (0.75 < S < 0.93) interdispersed with layers exhibiting anti-nematic order (−0.45 < S < −0.3). Both types of layers share the same director. Here, the particles organize with relative T-shape configurations, intermediate between coplanar and stacked. At still higher densities, further increase of ionic strength equivalent to κσ ≥ 4, leads to weakening of the positional order. Hexagonal crystals are replaced by hexagonal columnar liquid-crystals with no positional correlations along the nematic director.

To better characterize the orientationally disordered structures, we examined their translational and rotational dynamics by the dynamic Monte-Carlo method29. In Fig. 4, we have shown the self-intermediate scattering functions  and time orientational correlation functions

and time orientational correlation functions  computed for densities ρ* = 1 – 3, lower than those of the nematic phase at κσ = 20. Upon increasing the density, both translational and rotational relaxation times increase. Notably, in the random stacks phase, the orientational time correlation functions exhibit very little decay. This shows that upon approaching the nematic phase, the orientational relaxation becomes dramatically slow (Fig. 4b). In order to quantify the slowing down of dynamics, we show in Fig. 5 the long-time translational and rotational diffusion coefficients, extracted from self-intermediate scattering function (equivalently from mean-squared displacement) and orientational correlation function29 at κσ = 4 and 20. We find that increasing the density, both long-time translational and rotational diffusion coefficients of charged discs (big symbols) strongly decrease, with much steeper slope than the corresponding ones for hard discs (small symbols). Also, in the limit of very low ionic strength, the plastic crystals exhibit slow dynamics for translational coordinates and a fast decay for orientational ones (not shown here).

computed for densities ρ* = 1 – 3, lower than those of the nematic phase at κσ = 20. Upon increasing the density, both translational and rotational relaxation times increase. Notably, in the random stacks phase, the orientational time correlation functions exhibit very little decay. This shows that upon approaching the nematic phase, the orientational relaxation becomes dramatically slow (Fig. 4b). In order to quantify the slowing down of dynamics, we show in Fig. 5 the long-time translational and rotational diffusion coefficients, extracted from self-intermediate scattering function (equivalently from mean-squared displacement) and orientational correlation function29 at κσ = 4 and 20. We find that increasing the density, both long-time translational and rotational diffusion coefficients of charged discs (big symbols) strongly decrease, with much steeper slope than the corresponding ones for hard discs (small symbols). Also, in the limit of very low ionic strength, the plastic crystals exhibit slow dynamics for translational coordinates and a fast decay for orientational ones (not shown here).

(a) Self-intermediate scattering function Fs(q, t) computed at qσ = 7 and (b) orientational time correlation function  at κσ = 20 for densities ρ* = 1, 2 (isotropic fluid) and ρ* = 3 (random stacks).

at κσ = 20 for densities ρ* = 1, 2 (isotropic fluid) and ρ* = 3 (random stacks).

The time-scales are expressed in terms of characteristic time of free translational  and rotational

and rotational  diffusion coefficients, respectively.

diffusion coefficients, respectively.

The long-time translational diffusion coefficient  and rotational diffusion coefficient

and rotational diffusion coefficient  of charged discs normalized by their value in the infinite dilution limit, as a function of density.

of charged discs normalized by their value in the infinite dilution limit, as a function of density.

Left, large symbols: κσ = 20 where densities ρ* < 3 correspond to isotropic fluid and ρ* = 3 to random stacks. Right, large symbols: κσ = 4 where densities ρ* < 4 correspond to isotropic fluid and ρ* = 5 to intergrowth texture. For comparison, we have also shown the long-time diffusion coefficients of hard discs (smaller symbols connected with lines), which vary much less with density.

At higher densities where random stacks and intergrowth texture form, the spectacular slowing down of dynamics upon increase of density as a result of repulsive electrostatic interactions must have important consequences on viscoelastic properties of such charged platelet suspensions. One expects this strong slowing down of dynamics to be concomitant with a huge increase of viscosity, as found in dynamical measurements30,31, see the discussion below.

Discussion

Having a full overview of the phase diagram for charged disks, we compare our results with experimental observations. In comparison with experimental systems, we need to make a distinction between two types of charged colloidal plate-like suspensions: i) Gibbsite and Beidellite which are mainly driven by repulsive interactions and show an equilibrium isotropic-nematic transition before forming arrested states at higher densities. ii) Laponite type of clays which fall into arrested states already at very low volume fractions below the density range that one would expect formation of liquid crystals and the attractive interactions play a significant role in their phase behaviour13.

We first compare our simulations against the most extensively studied charged colloidal platelets: Gibbsite and Beidellite systems for which the repulsive interactions are predominant. Gibbsite and Beidellite show an I/N transition for a wide range of ionic strengths and platelet stacking is often observed in the nematic phase6,8. Moreover, Gibbsite suspensions also display a columnar hexagonal liquid-crystalline phase. These features are well captured in our simulations.

Fig. 6 shows the phase diagrams of Gibbsite32 and Beidellite6 versus reduced density ρ* and κσ (bottom/left axes) accompanied by the corresponding concentration/volume fraction and ionic strength (top/right axes) for quantitative comparison. Overall, the agreement between our simulations and the experimental phase diagrams for Gibbsite8 and Beidellite6 (shown in Fig. 6) is good. In both Gibbsite and Beidellite, for 10 < κσ < 20, a nematic phase of stacked platelets is found, although at densities lower than the one obtained in simulations. This discrepancy could be due to platelet polydispersity that usually widens the isotropic-nematic coexistence region. Moreover, in agreement with our simulations, a direct transition from isotropic to columnar hexagonal phases is observed for Gibbsite particles at lower ionic strengths. Upon further increase of density, a nematic gel is experimentally observed whereas we obtained a columnar hexagonal phase. At such high densities, we already anticipated that the suspensions cannot easily reach equilibrium, since the simulations require a slow and careful procedure to relax. Furthermore, the nematic gel of Gibbsite is a jammed state of oriented stacks (columns) that evolves towards a columnar hexagonal structure with time33. In addition, the recent measurements of long-time translational and rotational diffusion of isotropic suspensions of Gibbsite in DMSO30 are qualitatively in agreement with the results shown in Fig. 5. Although the ionic strengths for these experiments are not reported, we observe a similar trend for both  and

and  that decrease by more than 3 orders of magnitude upon approaching the isotropic-nematic transition.

that decrease by more than 3 orders of magnitude upon approaching the isotropic-nematic transition.

At this point, it is worth discussing our simulation results in connection with Laponite clay, another system of highly charged platelets. In contrast to Gibbsite and Beidellite, the I/N transition in Laponite suspensions is hindered by the occurrence of various kinetically trapped states at very low volume fractions (ϕ < 0.02) that exhibit aging and evolve from an initially liquid-like state towards either a gel or glassy non-ergodic states depending on clay concentration and ionic strength34. The range of densities and ionic strengths investigated in experiments corresponds to ρ* < 1 and34 1 ≤ κσ < 20. At such low densities, we observe a solid-like state (plastic crystal) only at small κσ = 1. This state could presumably only be glassy if polydispersity were considered35. Indeed, a Wigner glass at very low ionic strengths I < 10−4 has been reported for Laponite suspensions36,37. Upon further increase of ionic strength, we observe an ergodic repulsive isotropic liquid in the low-density region of our phase diagram which is at equilibrium unlike the aging Laponite suspensions. Therefore, our model system only based on repulsive interactions cannot fully explain the phase behavior of Laponite for larger ionic strengths, although we find that onset of slow dynamics shifts towards lower densities upon increase of ionic strength, similar to the trend observed for Laponite suspensions34. This points to the possible relevance of attractions13 or other specific interactions in this system. Nevertheless, our approach hints at the existence of a solid-like state at low ionic strengths, in agreement with the experimental observation of a Wigner glass36,37. Further ingredients in our modeling are required to reproduce the aging phenomenon observed for Laponite suspensions.

In conclusion, numerical simulations of charged platelets, interacting with an effective potential obtained from Poisson-Boltzmann theory, show a rich phase diagram that captures the generic features of charged colloidal platelet systems and provides us an insight about the influence of electrostatics on slowing down of dynamics upon varying density and ionic strength. The strong decrease of long-time translational and rotational diffusion found in our simulations is similar to the trend observed for Gibbsite suspensions30. The required procedure of slow charge increase, at moderate and high densities, echoes the difficulty for experimental systems to reach thermodynamic equilibrium. Better agreement with experiments could arguably be achieved by considering polydispersity, platelet flexibility, van der Waals attractions and interactions specific to each system such as solvation forces. The features brought to the fore here, though, can be considered as the non-specific effects pertaining to charged colloidal platelets. In particular, the robust form of our screened Coulomb potential leads to the formation of novel intergrowth texture, which calls for further experimental investigations in the isotropic region of the phase diagram, close to the I/N transition.

Methods

We carried out canonical (NVT) simulations on a system of N infinitely thin hard discs, i.e. zero thickness, with diameter σ in a cubic simulation box of side L with periodic boundary conditions using the anisotropic two-body potential of Eq. (1). The simulations were performed for a wide range of densities ρ* = Nσ3/L3 = 0.1 – 8 and ionic strengths giving rise to κσ = 1 – 20. The simulations were performed for T = 300 K giving rise to Bjerrum length λB = 6.96 Å. The dimensionless diameter σ/λB was taken to be 43 in the simulations, although we shall argue that its precise value, in a parameter range to be specified, is irrelevant. The number of particles varied between 103 ≤ N ≤ 104, although most of simulations were performed with N = 1372 discs corresponding to box sizes ranging from L/σ = 17.0 for ρ* = 0.1 to L/σ = 5.5 for ρ* = 8. For κσ ≤ 2, we adopted an Ewald-like scheme (neglect of the small Fourier space contribution) to take into account the relatively long range of the potential38. For κσ = 2 in the density range ρ* = 1–4, we confirmed that Ewald-like simulations performed with N = 1024 particles lead to the same results as with larger box sizes (N = 4000–10976, L/σ ≈ 15) without Ewald sums.

Due to relatively large values of the effective charge leading to a complex free energy landscape, we sometimes encountered, at large densities, ρ* ≥ 3, dependence of the final configuration on initial conditions. We circumvented this problem by simulated annealing39 i.e. we started from an initial equilibrium configuration of (uncharged) discs at the desired density, then increased the charge gradually from zero to the final value  . We performed (depending on the density and κσ) 0.3 – 1 × 106 MC cycles, (a cycle consisting of translation and rotation of the N particles) at each equilibration step before increasing the charge value. This gradual charge increment, similar to gradual cooling of the system for a fixed value of the effective charge, leads to reproducible results for independent simulation runs performed with different initial conditions, provided the charge increment between two subsequent steps is small enough, typically ΔZeffλB/σ ≤ 0.5.

. We performed (depending on the density and κσ) 0.3 – 1 × 106 MC cycles, (a cycle consisting of translation and rotation of the N particles) at each equilibration step before increasing the charge value. This gradual charge increment, similar to gradual cooling of the system for a fixed value of the effective charge, leads to reproducible results for independent simulation runs performed with different initial conditions, provided the charge increment between two subsequent steps is small enough, typically ΔZeffλB/σ ≤ 0.5.

We further performed dynamic Monte-Carlo simulations29 to obtain the intermediate scattering function and time orientational correlation functions of orientationally disordered systems. In this case, very small values of displacements were used and we performed 0.1 – 2 × 107 MC cycles to obtain the dynamical quantities.

References

Glotzer, S. C. & Solomon, M. J. Anisotropy of building blocks and their assembly into complex structures. Nature materials 6, 557–562 (2007).

Damasceno, P. F., Engel, M. & Glotzer, S. C. Predictive Self-Assembly of Polyhedra into Complex Structures. Science 337, 453–457 (2012).

Onsager, L. The effects of shape on the interaction of colloidal particles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 51, 627–659 (1949).

Ruzicka, B. & Zaccarelli, E. A fresh look at Laponite phase diagram. Soft Matter 7, 1268–1286 (2011).

Gabriel, J.-C. P., Sanchez, C. & Davidson, P. Observation of nematic liquid-crystal textures in aqueous gels of smectite clays. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 11139–11143 (1996).

Paineau, E. et al. Liquid-crystalline nematic phase in aqueous suspensions of a disk-shaped natural beidellite clay. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 15858–15869 (2009).

Michot, L. J. et al. Liquid-crystalline aqueous clay suspensions. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16101–16104 (2006).

Mourad, M. C. D. et al. Sol-gel transitions and liquid crystal phase transitions in concentrated aqueous suspensions of colloidal gibbsite platelets. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 11604–11613 (2009).

Sun, D., Sue, H.-J., Cheng, Z., Martnez-Ratn, Y. & Velasco, E. Stable smectic phase in suspensions of polydisperse colloidal platelets with identical thickness. Phys. Rev. E 80, 041704 (2009).

Liu, Z. et al. Synthesis, anion exchange and delamination of Co-Al layered double hydroxide: assembly of the exfoliated nanosheet/polyanion composite films &magneto-optical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128(14), 4872–4880 (2006).

Yamaguchi, D. et al. Aspect-ratio-dependent phase transitions and concentration fluctuations in aqueous colloidal dispersions of charged platelike particles. Phys. Rev. E 85, 011403 (2012).

Tanaka, H., Meunier, J. & Bonn, D. Nonergodic states of charged colloidal suspensions: repulsive and attractive glasses and gels. Phys. Rev. E 69, 031404 (2004).

Ruzicka, B. et al. Observation of empty liquids and equilibrium gels in a colloidal clay. Nature Materials 10, 56–60 (2011).

Jabbari-Farouji, S., Wegdam, G. H. & Bonn, D. Gels and glasses in a single system: evidence for an intricate free-energy landscape of glassy materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 065701 (2007).

Veerman, J. A. C. & Frenkel, D. Phase behavior of disklike hard-core mesogens. Phys. Rev. A 45, 5632–5648 (1992).

Marechal, M., Cuetos, A., Martinez-Haya, B. & Dijkstra, M. Phase behavior of hard colloidal platelets using free energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 094501 (2011).

Dijkstra, M., Hansen, J. P. & Madden, P. A. Gelation of a clay colloid suspension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2236–2239 (1995).

Kutter, S., Hansen, J., Sprik, M. & Boek, E. Structure and phase behavior of a model clay dispersion: A molecular-dynamics investigation. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 311–323 (2000).

Mossa, S., de Michele, C. & Sciortino, F. Aging in a Laponite colloidal suspension: A Brownian dynamics simulation study. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014905 (2007).

Delhorme, M., Jönsson, B. & Labbez, C. Monte Carlo simulations of a clay inspired model suspension: the role of rim charge. Soft Matter 8, 9691–9704 (2012).

Morales-Anda, L., Wensink, H. H., Galindo, A. & Gil-Villegas, A. Anomalous columnar order of charged colloidal platelets. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 034901 (2012).

Agra, R., Trizac, E. & Bocquet, L. The interplay between screening properties and colloid anisotropy: Towards a reliable pair potential for disc-like charged particles. Eur. Phys. J. E 15, 345–357 (2004).

Álvarez, C. & Téllez, G. Screening of charged spheroidal colloidal particles. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 144908 (2010).

Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer Simulation of Liquids (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987).

van Roij, R., Dijkstra, M. & Hansen, J.-P. Phase diagram of charge-stabilized colloidal suspensions: van der Waals instability without attractive forces. Phys. Rev. E 59, 2010 (1999).

Denton, A. R. Coarse-Grained Modeling of Charged Colloidal Suspensions: From Poisson-Boltzmann Theory to Effective Interactions in Electrostatics of Soft and Disordered Matter in “Proceedings of the CECAM Workshop” New Challenges in Electrostatics of Soft and Disordered Matter (Pan Stanford, 2013).

Hynninen, A.-P. & Dijkstra, M. Phase diagrams of hard-core repulsive Yukawa particles. Phys. Rev. E 68, 021407 (2003).

Lindsay, H. M. & Chaikin, P. M. Elastic properties of colloidal crystals and glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 76, 3774–3782 (1982).

Jabbari-Farouji, S. & Trizac, E. Dynamic Monte Carlo simulations of anisotropic colloids. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 054107 (2012).

Kleshchanok, D., Heinen, M., Nagele, G. & Holmqvist, P. Dynamics of charged gibbsite platelets in the isotropic phase. Soft Matter 8, 1584–1592 (2012).

Jabbari-Farouji, S., Zargar, R., Wegdam, G. & Bonn, D. Dynamical heterogeneity in aging colloidal glasses of Laponite. Soft Matter 8, 5507–5512 (2012).

van der Beek, D. & Lekkerkerker, H. N. W. Liquid crystal phases of charged colloidal platelets. Langmuir 20, 8582–8586 (2004).

Mourad, M. C. D., Byelov, D. V., Petukhov, A. V. & Lekkerkerker, H. N. W. Structure of the repulsive gel/glass in suspensions of charged colloidal platelets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 494201 (2008).

Jabbari-Farouji, S., Tanaka, H., Wegdam, G. H. & Bonn, D. Multiple nonergodic disordered states in Laponite suspensions: A phase diagram. Phys. Rev. E. 78, 061405 (2008).

Zaccarelli, E., Andreev, S., Sciortino, F. & Reichman, D. R. Numerical Investigation of Glassy Dynamics in Low-Density Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 195701 (2008).

Levitz, P., Lecolier, E., Mourchid, A., Delville, A. & Lyonnard, S. Liquid-solid transition of Laponite suspensions at very low ionic strength: Long-range electrostatic stabilisation of anisotropic colloids. Europhys. Lett. 49, 672–677 (2000).

Bonn, D., Tanaka, H., Wegdam, G., Kellay, H. & Meunier, J. Aging of a colloidal “Wigner” glass. Europhys. Lett. 45, 52–57 (1998).

Salin, G. & Caillol, J. M. Ewald sums for Yukawa potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 10459–10463 (2000).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science 220, 671–680 (1983).

Acknowledgements

S. J.-F. would like to acknowledge the financial support from Foundation Triangle de la Physique and IEF Marie-Curie fellowship. We are also grateful to A. Maggs and H.H. Wensink for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.-F. carried out the simulations, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.-J.W. performed the simulations and analysed the data. P.D. participated in understanding of results and writing of the manuscript. P.L. contributed to the comparison of results with experiments. E.T. initiated and supervised the research. All authors contributed to rationalizing the data.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jabbari-Farouji, S., Weis, JJ., Davidson, P. et al. On phase behavior and dynamical signatures of charged colloidal platelets. Sci Rep 3, 3559 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03559

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03559

This article is cited by

-

Tracking the time evolution of soft matter systems via topological structural heterogeneity

Communications Materials (2022)

-

A liquid-crystalline hexagonal columnar phase in highly-dilute suspensions of imogolite nanotubes

Nature Communications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.