Abstract

We propose a method of resolving a spatially coherent signal, which contains on average just a single photon, against the background of local noise at the same frequency. The method is based on detecting the signal simultaneously in several points more than a wavelength apart through the entangling interaction of the incoming photon with the quantum metamaterial sensor array. The interaction produces the spatially correlated quantum state of the sensor array, characterised by a collective observable (e.g., total magnetic moment), which is read out using a quantum nondemolition measurement. We show that the effects of local noise (e.g., fluctuations affecting the elements of the array) are suppressed relative to the signal from the spatially coherent field of the incoming photon as  , where N is the number of array elements. The realisation of this approach in the microwave range would be especially useful and is within the reach of current experimental techniques.

, where N is the number of array elements. The realisation of this approach in the microwave range would be especially useful and is within the reach of current experimental techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

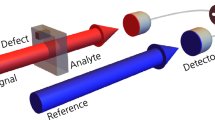

The ultimate goal and the theoretical limit of weak signal detection is the ability to detect a single photon against a noisy background. In this situation the inescapable noise produced by the measuring device itself may be the main obstacle, but the uncertainty principle restricts possible experimental techniques of increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. For example, a weak classical signal from a remote source can be distinguished from the local noise at the same frequency through its spatial correlations (using phase sensitive detectors; coincidence counters; etc) - i.e., by sensing its wave front. This method seems impossible in the case of a single incoming photon, since it is usually assumed that it can only be detected once. Nevertheless such a conclusion would be too hasty. In this paper we show, that a combination of a quantum metamaterial1 (QMM)-based sensor array and quantum non-demolition2,3 (QND) readout of its quantum state allows, in principle, to detect a single photon in several points. Actually, there are a few possible ways of doing this, with at least one within the reach of current experimental techniques for the microwave range.

We will illustrate the possible implementations of this scheme using a simplified model, an example of which is shown in Fig. 1. Here the QMM array is modelled by a set of N qubits, which are coupled to two LC circuits: the one (A) represents the input mode and the other (B) the readout. This model is closest to the case of microwave signal detection using superconducting qubits, which is both most interesting (at least from the point of view of radioastronomy) and most feasible, as attested by the signal progress achieved in the recent years. In particular, several schemes of microwave photon detectors based on Josephson qubits and Josephson qubit metamaterials, capable of detecting a single photon, were proposed4,5,6 and realized7; the entanglement detection and quantum state tomography were demonstrated as well8,9,10,11. Nevertheless our approach and conclusions apply generally, mutatis mutandis (e.g., to the case of photonic crystal decorated with two level systems13, an array of SQUIDs14 or atoms in an optical lattice12). We will therefore begin by discussing how such a detector system could work in principle. We then go to demonstrate that a clear distinction between a single incident photon and the vacuum can be seen in the response of a simple two-qubit detector array using a fully quantum mechanical model. Finally we explore the role of inter-qubit coupling and increasing the size of the QMM array using a semi-classical mean field approach.

Results

Mathematical model

The system of Fig. 1 is described by the Hamiltonian

Here

describes the input circuit, excited by the incoming field;

is the Hamiltonian of the qubits;

is the Hamiltonian of the output circuit with the probing field, used in case of IMT readout; and

describe the coupling between the QMM array and the input and output circuits. The effects of ambient noise can be taken into account, e.g., by adding an appropriate term Hnoise to (1) or by including Lindblad operators in the master equation for the density matrix of the system (see, e.g.15).

Numerical results for two sensor qubits

To investigate the level of sensitivity of the proposed detector system, we consider the example of a QMM array comprised of two qubits coupled to the input mode and readout oscillator, as shown in Fig. 1. We assume that the input field has a given number of photons incident on it and is initially found in a coherent state, |α〉, with an average of |α|2 photons and therefore take f(t) = 0. We also take h(t) = 0 and assume that the intrinsic noise in the detector system is sufficient to drive the readout field and allow detection of the incident photons.

In order to fully account for the effects of decoherence and measurement, we make use of the quantum state diffusion formalism16 to describe the evolution of the state vector |ψ〉;

where |dψ〉 and dt are the state vector and time increments respectively,  are the Lindblad operators and dξ are the stochastic Wiener increments which satisfy

are the Lindblad operators and dξ are the stochastic Wiener increments which satisfy  and

and  .

.

To model the natural effects of decoherence on the qubits we have the Lindblads  and

and  acting on both qubits. These operators describe relaxation in the z-direction and dephasing in the x-y plane of the Bloch sphere respectively. To account for the weak continuous measurement of the output field we also take

acting on both qubits. These operators describe relaxation in the z-direction and dephasing in the x-y plane of the Bloch sphere respectively. To account for the weak continuous measurement of the output field we also take  . From the real and imaginary parts of

. From the real and imaginary parts of  we can extract the expectation values for the position

we can extract the expectation values for the position  and momentum

and momentum  operators.

operators.

We assume the qubits act in the σz basis with  and therefore Δ = 0. Typical flux qubits work at a frequency of the order of 10 GHz, whereas the relaxation and dephasing rates are usually of the order of 10 MHz17, therefore we take in the Lindblad operators Γz/ωq = Γxy/ωq = 10−3. For the input field, we take ωa/ωq = 0.5 assuming an incident photon off-resonance with the qubit. We take ωb/ωq = 0.5 assuming the readout oscillator is also off-resonance with the qubit but resonant with the input field. For high quality tank circuits and transmission lines the lifetime is typically relatively long compared to the operating frequency18,19,20 and we therefore take Γb/ωb = 10−3. Our choice of coupling parameters ga/ωq = gb/ωq = 0.01 is also in line with the experiment19,20.

and therefore Δ = 0. Typical flux qubits work at a frequency of the order of 10 GHz, whereas the relaxation and dephasing rates are usually of the order of 10 MHz17, therefore we take in the Lindblad operators Γz/ωq = Γxy/ωq = 10−3. For the input field, we take ωa/ωq = 0.5 assuming an incident photon off-resonance with the qubit. We take ωb/ωq = 0.5 assuming the readout oscillator is also off-resonance with the qubit but resonant with the input field. For high quality tank circuits and transmission lines the lifetime is typically relatively long compared to the operating frequency18,19,20 and we therefore take Γb/ωb = 10−3. Our choice of coupling parameters ga/ωq = gb/ωq = 0.01 is also in line with the experiment19,20.

In the beginning, the output field is in the vacuum state and the qubits are in the superposition state  . We then simulate QSD trajectories with the input field initially in the vacuum state and coherent states with an average both of 1 and 5 photons. The resulting spectra of the readout mode for a typical quantum trajectory are shown in Fig. 2. The most important conclusion is that there is a clear difference to the readout depending on whether a photon is incident upon the detector or not.

. We then simulate QSD trajectories with the input field initially in the vacuum state and coherent states with an average both of 1 and 5 photons. The resulting spectra of the readout mode for a typical quantum trajectory are shown in Fig. 2. The most important conclusion is that there is a clear difference to the readout depending on whether a photon is incident upon the detector or not.

Power spectra for the readout field's position  and momentum

and momentum  quadratures for a typical QSD realisation in the presence of local noise.

quadratures for a typical QSD realisation in the presence of local noise.

The input field is in a coherent state with the average number of photons equal 0 (black dashed line, bottom), 1 (red line, middle) or 5 (blue line, top). Note the significant difference between the data for zero and one photons in the incoming signal.

When the input field is initially in a coherent state the peak in the power spectral density is shifted to lower frequencies and decreases in magnitude compared to the clear sharp peak seen when the input field is in the vacuum state. The response is smeared out across the low frequency region leading to a higher average power when there photons there are photons incident upon the detector. This is particularly clear in the case of the position operator where there is a clear distinction of approximately one order of magnitude.

One could object that a coherent input state actually contains an infinite number of photons and thus cannot be considered a valid test for the proposed approach. In order to check this, we have performed the same simulations for the input field in a Fock state (Fig. 3). The results show that the distinction between the responses to different input fields remains significant and still allows to reliably distinguish between them.

Power spectra for the readout field's position  and momentum

and momentum  quadratures for a typical QSD realisation in the presence of local noise.

quadratures for a typical QSD realisation in the presence of local noise.

The input field is in a Fock state with the number of photons equal 0 (black dashed line, bottom), 1 (red line, middle) or 5 (blue line, top). The difference between the data for zero and one photons in the incoming signal remains qualitatively the same as in the case of a coherent input state.

Scaling of the quantum metamaterial sensor array

In order to further investigate the role of increased number of qubits and of interqubit couplings, we consider the Hamiltonian

with qubits driven by common harmonic off-resonance signal (modeling the input Va of Eq.(1)) and local noise coupled through σz:

Here 〈ξ(t)〉 = 0 and 〈ξj(t)ξl(t′)〉 = δjlδ(t − t′) and we take  , ω/Δ = 1.13 and D/Δ = 10−6.

, ω/Δ = 1.13 and D/Δ = 10−6.

We represent the effects of decoherence on the evolution of the sensor qubits by solving the Lindblad master equation

with relaxation, Lz and dephasing, Lxy, Lindblad operators acting on each qubit, where Γz/Δ = Γxy/Δ = 10−3.

In the case of N uncoupled qubits (where g = 0), we can describe the system by N independent master equations for a single-qubit density matrix and average the observable quantities. This data is shown in Fig. 4a,b. The spectral density of the z-component of the total “spin” demonstrates a small, but distinct peak due to the external drive, in addition to the large noise-driven signal. The increase of the number of qubits, predictably, increases the signal to noise ratio. The increase is in qualitative agreement with the  behaviour, expected from the analytic estimate given below in the Discussion section, though numerically somewhat smaller (approximately doubling rather than tripling as N increases from 1 to 9; see Fig. 4a, inset).

behaviour, expected from the analytic estimate given below in the Discussion section, though numerically somewhat smaller (approximately doubling rather than tripling as N increases from 1 to 9; see Fig. 4a, inset).

(Top) Spectral density of total detector “spin” Sz in a qubit in the presence of noise and drive.

The signal due to drive is a small thin peak on the left of the resonant noise response. Inset: Signal to noise ratio as the function of number of qubits. (Centre) Same in case of 8 uncoupled qubits (where g = 0). Inset: A close up of the signal-induced feature. The noise is suppressed in case of 8 uncoupled qubits (blue) compared to the case of a single qubit (red). (Bottom) The spectral density of Sz in case of two coupled qubits, where g/Δ = 2. Note that the significant shift of the resonant frequency of the system (position of the noise-induced feature). Inset: Signal response amplitude (left) and signal to noise ratio (right) as functions of the coupling strength.

The qubit-qubit coupling also increases the signal to noise ratio. We now solve the master equation for two coupled qubits and the results show that while the overall signal amplitude is suppressed by qubit-qubit coupling, the relative amplitude of the signal significantly increases (Fig. (4c)).

Discussion

For a simple illustration of how a single photon can be simultaneously detected at several points in space, consider the case when there is one photon in the input circuit, two identical and identically coupled to it noiseless qubits are initially in their ground state and the readout circuit is switched off. In this case the system undergoes vacuum Rabi oscillations and its wave function is21

At the moments when the first term vanishes,  , the qubits are in the maximally entangled Bell state and the QND measurement of their summary “spin” in z-direction realizes the observation of a single photon's presence (a Fock state |1〉 of the circuit A) at two spatially separated points (locations of the qubits 1 and 2).

, the qubits are in the maximally entangled Bell state and the QND measurement of their summary “spin” in z-direction realizes the observation of a single photon's presence (a Fock state |1〉 of the circuit A) at two spatially separated points (locations of the qubits 1 and 2).

A literal realisation of such a scheme for observing a single photon's wavefront in multiple points is theoretically possible, but hardly advisable: The resonant transfer of the incoming photon into the qubit array and back is vulnerable to absorption in one of the qubits. A better opportunity is presented by the dispersive regime, when the mismatch between the qubits' and incoming photon's resonant frequencies,  , allows to use the Schrieffer-Wolff transformation. If Δ = 0, the interaction term Va in (1) is reduced to15,22

, allows to use the Schrieffer-Wolff transformation. If Δ = 0, the interaction term Va in (1) is reduced to15,22

Now the effect of the input field on the detector qubits is the additional phase gain proportional to the number of incoming photons, which can be read out using a QND technique.

Note that in addition to (11) we will also obtain the effective coupling between qubits through the vacuum mode of the oscillator (see, e.g.23). In the case of identical qubits and coupling parameters it is

If the number of qubits in the matrix is large enough, this term can be approximated by a “mean field” producing an effective “tunneling” for each individual qubit,  .

.

In the following, it will be convenient to account for the ambient noise sources through the term

in the Hamiltonian. In agreement with our assumptions, these fluctuations in different qubits are uncorrelated: 〈ξj(t)ξk(t′)〉 ∝ δjk; 〈ξj(t)ηk(t′)〉 = 0.

Let us excite the input circuit with a resonant field, f(t) = fe(t) exp[−iωat] + c.c., with slow real envelope function fe(t). Neglecting for the moment the rest of the system, due to the weakness of the effective coupling g2/δΩ in (11), we can write for the wave function of the input circuit

and

Here D(α) with

is the displacement operator

Acting on a vacuum state, it produces a coherent state, D(α)|0〉 = |α〉. Therefore, assuming that the input circuit was initially in the vacuum state, the average

Therefore the action of the incoming field on the qubits in the dispersive regime can be approximated by replacing the terms Ha and Va in the Hamiltonian (1) with

In the Heisenberg representation the “spin” of the jth qubit,

satisfies the Bloch equations, which in case of zero bias and only z-noise  and neglecting for the moment the interaction with the readout circuit, take the form

and neglecting for the moment the interaction with the readout circuit, take the form

or, introducing  ,

,

Let us initialize the qubit in an eigenstate of  (i.e., in an eigenstate of unperturbed qubit Hamiltonian, since

(i.e., in an eigenstate of unperturbed qubit Hamiltonian, since  ). Then

). Then  ,

,  (i.e., 1 or −1), and, assuming the slowness of Δeff(t), the equations (22) can be solved perturbatively:

(i.e., 1 or −1), and, assuming the slowness of Δeff(t), the equations (22) can be solved perturbatively:

Assuming identical qubits identically coupled to the input circuit, we finally obtain for the collective variable (z-component of the total qubit “spin” of the QMM array)

The second term in the brackets is the result of local fluctuations affecting separate qubits and is therefore, in the standard way,  times suppressed compared to the first term (due to the regular evolution produced by the spatially coherent input photon field). The variable Sz can be read out by the output LC circuit, e.g., by monitoring the equilibrium current/voltage noise in it18. The signal will be proportional to the spectral density 〈(Sz)2〉ω, i.e. to the Fourier transform of the correlation function 〈Sz(t + τ)Sz(t)〉. Due to the quantum regression theorem24, the relevant correlators satisfy the same equations (22) as the operator components themselves and the “regular” and “noisy” terms originating from (24) will indeed be O(N2) and O(N) respectively.

times suppressed compared to the first term (due to the regular evolution produced by the spatially coherent input photon field). The variable Sz can be read out by the output LC circuit, e.g., by monitoring the equilibrium current/voltage noise in it18. The signal will be proportional to the spectral density 〈(Sz)2〉ω, i.e. to the Fourier transform of the correlation function 〈Sz(t + τ)Sz(t)〉. Due to the quantum regression theorem24, the relevant correlators satisfy the same equations (22) as the operator components themselves and the “regular” and “noisy” terms originating from (24) will indeed be O(N2) and O(N) respectively.

Though the possibility to observe a single photon's wave-front requires the detection of a weak, remote signal against the background of local fluctuations, the standard signal-to-noise ratio  due to the N-element coherent uncoupled QMM array is unlikely to be of much practical use. Noticing that the effect of the input field is nothing but a simple one-qubit quantum gate applied to each element of the array and that introducing a simple qubit-qubit coupling scheme can improve matters, we can ponder a more sophisticated approach. By performing on a group of qubits a set of quantum manipulations, which would realize a quantum error correction routine, one can hope to improve the sensitivity of the system.

due to the N-element coherent uncoupled QMM array is unlikely to be of much practical use. Noticing that the effect of the input field is nothing but a simple one-qubit quantum gate applied to each element of the array and that introducing a simple qubit-qubit coupling scheme can improve matters, we can ponder a more sophisticated approach. By performing on a group of qubits a set of quantum manipulations, which would realize a quantum error correction routine, one can hope to improve the sensitivity of the system.

Finally, it is worth noting that the proposed scheme is not dissimilar from the method of quantum enhanced measurements26, which allows to reach the so called Heisenberg limit when determining the value of an observable by measuring N independent copies of the relevant quantum system with accuracy scaling as 1/N rather than the “standard quantum limit”  (as required by a theorem from quantum metrology25). The seeming violation is due to the fact that in26 the systems are made to interact with a common “quantum bus” (and are no longer independent) and it is the state of the bus that is consequently measured.

(as required by a theorem from quantum metrology25). The seeming violation is due to the fact that in26 the systems are made to interact with a common “quantum bus” (and are no longer independent) and it is the state of the bus that is consequently measured.

In conclusion, we have shown the possibility in principle to detect the wavefront of a spatially coherent signal containing on average a single photon, by using the quantum coherent set of spatially separated qubits (a quantum metamaterial sensor array). The key feature of this approach is the combination of the nonlocal photon interaction with the collective observable of the QMM array and its QND measurement. The realisation of our approach would allow to greatly improve the sensitivity of radiation detectors by suppressing the effects of local noise as well as lowering the detection bar to the minimum allowed by the uncertainty principle.

Methods

Numerical methods

In the fully quantum mechanical treatment of a detector consisting of two sensor qubits we represent both the input and output fields in a truncated basis comprised of the first 30 number states. The deterministic part of the quantum state diffusion evolution (the first two terms of (6)) is computed using a fifth-order Runge-Kutta formula with adaptive step size, while the stochastic part of each time step (the third term in (6)) is integrated using the Euler method. After 150 periods of ωb the power spectra of the output field's position  and momentum

and momentum  quadratures are taken using a fast Fourier transform.

quadratures are taken using a fast Fourier transform.

In the semi-classical treatment of a quantum metamaterial sensor array we solve the Lindblad master equation numerically using the Euler method. For the case of two coupled qubits, this is done using the generalized Bloch parametrization of the two-qubit density matrix:

as in27.

References

Rakhmanov, A., Zagoskin, A., Savel'ev, S. & Nori Quantum metamaterials: Electromagnetic waves in a Josephson qubit line. Phys. Rev. B 77, 144507 (2008).

Braginsky, V. B. & Khalili, F. Ya. Quantum Measurement. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995).

Lupascu, A. et al. Quantum non-demolition measurement of a superconducting two-level system. Nature Physics 3, 119–125 (2007).

Romero, G., Garcia-Ripoll, J. J. & Solano, E. Microwave Photon Detector in Circuit QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 137602 (2009).

Peropadre, B. et al. Approaching perfect microwave photodetection in circuit QED. Phys. Rev. A 84, 063834 (2011).

Poudel, A., McDermott, R. & Vavilov, M. G. Quantum efficiency of a microwave photon detector based on a current-biased Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 86, 134506 (2012).

Chen, Y.-F. et al. Microwave Photon Counter Based on Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217401 (2011).

Menzel, E. P. et al. Dual-Path State Reconstruction Scheme for Propagating Quantum Microwaves and Detector Noise Tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 100401 (2010).

Eichler, C. et al. Observation of Entanglement between Itinerant Microwave Photons and a Superconducting Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 240501 (2012).

Menzel, E. P. et al. Path Entanglement of Continuous-Variable Quantum Microwaves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 250502 (2012).

DiCandia, R. et al. Dual-Path Method for Propagating Quantum Microwaves. arXiv:1308.3117 [quant-ph] (2013).

Bloch, I. Ultracold quantum gases in optical lattices. Nature Physics 1, 23 (2005).

Greentree, A. D., Fairchild, B. A., Hossain, F. M. & Prawer, S. Diamond integrated quantum photonics. Materials Today 11, 22 (2008).

Stiffell, P. B., Everitt, M. J., Clark, T. D., Harland, C. J. & Ralph, J. F. Quantum downconversion and multipartite entanglement via a mesoscopic superconducting quantum interference device ring. Phys. Rev. B 72, 014508 (2005).

Zagoskin, A. M. Quantum Engineering: Theory and Design of Quantum Coherent Structures. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011).

Percival, I. Quantum State Diffusion. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998).

Astafiev, O. et al. Resonance Fluorescence of a Single Artificial Atom. Science 327, 840–843 (2010).

Il'ichev, E. et al. Continuous Monitoring of Rabi Oscillations in a Josephson Flux Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 097906 (2003).

Fink, J. M. et al. Climbing the Jaynes-Cummings ladder and observing its nonlinearity in a cavity QED system. Nature 454, 315–318 (2008).

Abdumalikov, A. A., Astafiev, O., Nakamura, Y., Pashkin, Yu. A. & Tsai, J. S. Vacuum Rabi splitting due to strong coupling of a flux qubit and a coplanar-waveguide resonator. Phys. Rev. B 78, 180502 (2008).

Smirnov, A. Yu. & Zagoskin, A. M. Quantum Entanglement of Flux Qubits via a Resonator. arXiv:cond-mat/0207214 (2002).

Blais, A., Huang, R.-S., Wallraff, A., Girvin, S. M. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: An architecture for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 69, 062320 (2004).

Makhlin, Yu., Schön, G. & Shnirman, A. Quantum-state engineering with Josephson-junction devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 357–400 (2001).

Gardiner, C. W. & Zoller, P. Quantum Noise. Springer, Berlin (2004).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum Metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Braun, D. & Martin, J. Heisenberg-limited sensitivity with decoherence-enhanced measurements. Nature Communications 2, 223 (2011).

Savel'ev, S. et al. Two-qubit parametric amplifier: Large amplification of weak signals. Phys. Rev. A 85, 013811 (2012).

Acknowledgements

AMZ, RDW, ME and SS were supported by the John Templeton Foundation. EI acknowledges the financial support of the EU through the project iQIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.Z., V.K.D. and D.R.G. formulated the problem. A.M.Z. and S.S. proposed the detection strategies and models. A.M.Z., E.I. and M.E. suggested the possible implementations and evaluated their feasibility. A.M.Z., D.R.G. and J.A. performed the analytical calculations. S.S., M.E. and R.D.W. performed the numerical calculations. All authors contributed to the discussion of the physical content of the investigated effects and their possible applications and to the writing of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zagoskin, A., Wilson, R., Everitt, M. et al. Spatially resolved single photon detection with a quantum sensor array. Sci Rep 3, 3464 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03464

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03464

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.