Abstract

Several studies provide evidence of a link between vector-borne disease outbreaks and El Niño driven climate anomalies. Less investigated are the effects of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Here, we test its impact on outbreak occurrences of 13 infectious diseases over Europe during the last fifty years, controlling for potential bias due to increased surveillance and detection. NAO variation statistically influenced the outbreak occurrence of eleven of the infectious diseases. Seven diseases were associated with winter NAO positive phases in northern Europe and therefore with above-average temperatures and precipitation. Two diseases were associated with the summer or spring NAO negative phases in northern Europe and therefore with below-average temperatures and precipitation. Two diseases were associated with summer positive or negative NAO phases in southern Mediterranean countries. These findings suggest that there is potential for developing early warning systems, based on climatic variation information, for improved outbreak control and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite a limited knowledge primarily focused on vector-borne pathogens1,2,3, climate change is commonly predicted to impact the transmission of infectious diseases and their geographical distribution4,5. This may be due to the impact of changes in mean temperature or rainfall6 and has been illustrated through statistical evaluation of pathogen dynamic trends and shifts in climatic factors7,8.

Climate variability may also affect outbreaks of infectious diseases9. Increase in the transmission of different vector-borne diseases such as Murray Valley encephalitis, bluetongue, Rift Valley fever, African horse sickness, Ross River virus disease, visceral leishmaniasis, dengue and malaria6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 have been linked to the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO, an intermittent inversion of Pacific Ocean thermal gradients) driven climate anomalies22,23. Associations with the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), another index of climate variability, have also been investigated for several other infectious diseases including Lyme borreliosis24, tularaemia25 and measles26.

Although climate change is a global phenomenon, its effects vary by location, making regional studies of potential impacts important. In Europe, several studies have provided important insights into the consequences of climate change on infectious diseases and evidence for resulting epidemiological changes in individual diseases, such as bluetongue27. However, few studies have taken a comparative approach considering effects upon multiple diseases together28,29 and even fewer have explored the potential links between climate variability and disease outbreaks in Europe as an entity30. While the ENSO index does not seem to be an accurate index of climate variability in Europe, the NAO does31,32.

Positive and negative phases of the NAO reflect patterns of pressure anomalies and are associated with changes in temperature and precipitation patterns extending from eastern North America to western and central Europe. Strong positive phases of the NAO tend to be associated with above-average temperatures and precipitation across northern and central Europe and above-average temperatures and below-average precipitation over Mediterranean countries (Southern Europe, North African and Middle-Eastern countries). Opposite patterns of temperature and precipitation abnormalities are typically observed during strong negative phases of the NAO (www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov). However, this pattern seems to be more pronounced in winter and climate variability in Mediterranean countries appears to also be linked to the Indian Monsoon33.

Research covering Europe is limited compared, for example, to the USA. The association between the NAO and the annual incidence rate of 13 viral, bacterial and protozoan human diseases in the Czech Republic from 1951 to 2003 was investigated by Hubálek30. According to his analyses, toxoplasmosis and infectious mononucleosis were significantly and positively correlated and leptospirosis was negatively correlated with the NAO. For toxoplasmosis, it was proposed that the warmer winter associated with a positive NAO, lagged one year (meaning it occurred one year later), would enhance populations of rodents, the intermediate hosts of the protist Toxoplasma gondii. For leptospirosis, higher precipitation in negative NAO years, lagged two years, would result in increasing populations of field rodents, the main reservoir of the bacteria Leptospira interrogans30. A similar conclusion was reached for hantavirus outbreaks in the USA in relation to El Niño (ENSO), with heavy rains or warm winters boosting mast seeding and thus favouring rodent populations, the reservoirs of hantavirus34. Similar associations were also found for hantavirus in Belgium35.

This study aimed to test the influence of NAO variability upon outbreak occurrences of several infectious diseases across Europe observed over recent decades. Interpretation of the results would also need to consider that non-climate related factors such as an increase in disease reporting over time may be important contributors to observed disease trends.

Results

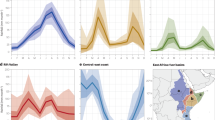

For eleven diseases, the occurrence of outbreaks was significantly related to the NAO monthly index. These include adenovirus infection, measles, Q fever, Aseptic viral meningitis, enterovirus infection, gastroenteritis, typhoid fever, tularaemia, hantavirus infection, hepatitis A and shigellosis. A twelfth disease, trichinosis, was associated with the NAO monthly index at a 94% level of statistical certainty. The remaining disease, tuberculosis, was not associated with NAO monthly index.

Mean health expenditure was significantly associated with year (Fig. 1C) (Adjusted R2 = 0.967, F1,47 = 1390, P = 0.00001), as was per capita GDP (Adjusted R2 = 0.995, F1,47 = 9254, P < 0.00001). Per capita GDP and per capita health expenditure across European countries were significantly correlated (Adjusted R2 = 0.9598, F1,47 = 1148, P < 0.00001). We treat per capita health expenditure as a proxy for the effectiveness of surveillance reporting.

A. changes in the number of countries reporting at least one outbreak of the diseases of interest in this study from 1950 to 2009 (data from GIDEON, see M&M).B. Changes in the number of diseases having at least one reported outbreak from 1950 to 2009 (data from GIDEON, see M&M). C. Evolution of mean health expenditure in Europe from 1960 to 2009 (data from OECD, see M&M) (base 100 = health expenditure in 2000).

We used Generalized Linear Modelling (GLM) to model the association of monthly NAO on the number of outbreaks using smoothed spline fitting function. The best model was selected using the AIC criterion for each infectious disease (ID) studied, given in 1Table 2.

Of the diseases found to be associated with NAO indices, seven (adenovirus infection, measles, Aseptic viral meningitis, Q fever, gastroenteritis, tularaemia, shigellosis and trichinosis) were associated with the winter positive phases in northern Europe (from November to February), therefore with above-average temperatures and above-average precipitation.

Two diseases were associated with negative NAO at other times of year: enterovirus infection showed an association with the negative summer NAO index in northern Europe; and hantavirus infection was associated with the negative spring NAO index in northern Europe.

Typhoid fever showed an association with positive winter NAO index in southern Europe, which corresponds to below-average temperature and below-average precipitation. Hepatitis A showed an association with negative winter NAO index in southern Europe with above-average temperatures and above-average precipitation.

Discussion

For the majority of the diseases, the detrended number of outbreaks was significantly related to the positive autumn and winter NAO monthly index values in southern countries, or to the negative autumn and winter NAO monthly index values in southern countries. The observed differences in results between northern and southern Europe are in accord with the differential influences of the NAO on Europe, particularly in winter31, although climate variability in Mediterranean countries is also influenced by the Indian monsoon33.

Associations between the occurrence of different infectious diseases and climate variables have been reported worldwide. Evidence of changes in influenza risk attributable to climate variability comes from Choi et al.49, who found a lower mortality risk due to influenza during El Niño events compared to periods of normal weather. Sultan et al.50 showed that climate variability can also affect the occurrence of meningococcal meningitis, with a correlation found between the onset of meningococcal meningitis epidemics and the winter maximum of an atmospheric index.

In this study, outbreaks of adenovirus infection were associated with positive values of the NAO, which is consistent with other findings in the literature, in which increased precipitation has been reported as boosting the risk of adenovirus infection39. The study also found associations between Q fever and measles with positive values of summer NAO, which are in accordance with previous observations at country level for Q fever in the Netherlands41 and measles in England and Wales26.

We found three water-borne diseases (enterovirus infection, viral gastroenteritis and shigellosis) were associated with the positive summer values of the NAO index in northern Europe (wet climate), whereas typhoid fever was correlated with negative values of the NAO in northern Europe and the positive values of the NAO in southern Europe (dry climate). This confirms previous work suggesting that water-borne diseases are affected by climate variability; more specifically heavy rainfall events affecting enterovirus infection in arid tropical regions43 and periods of high temperature affecting viral gastroenteritis44 and typhoid fever (Table 1). Further, bacillary dysentery has previously been shown to be affected by climate variations and particularly El Niño51.

Hantavirus outbreaks in northern Europe were associated with a negative spring NAO with two years lag, which is in agreement with the findings of Tersagoa et al.35 in Belgium. Heavy rains or warm winters and springs boost mast seeding and, with a certain time lag, favour rodent populations as reservoirs of hantavirus.

Palo et al.52 showed that negative values of the NAO index were associated with high numbers of human cases of tularaemia in Sweden. Epidemiological investigations of summer outbreaks of tularemia in two localities in Sweden showed complex associations with landscape changes (wetland restoration) and recreational activities53. We found the same pattern in our analysis, however at the level of all northern European countries.

Warmer temperatures have been hypothesized to increase the number of amplification cycles for food animal parasites such as Trichinella species, which may explain the positive association between the winter NAO phase and trichinosis outbreaks in northern Europe. An alternative explanation might be that these climatic conditions would lead to longer summer hunting seasons and consequently to an increased exposure of humans to the pathogens54. The same may also apply to tulaeremia. However, in Europe, most trichinosis infections are associated with wild boar being eaten undercooked and any association with climatic parameters should be evaluated whilst also taking account consumer behaviour.

Climate variability may have a direct impact on pathogens via effects on survival outside of the host and dissemination. Climate variability may also act indirectly, by acting on other factors which affect the chances of transmission, such as changes in social behaviour, as mentioned above for measles. As emphasized by Randolph55 and Evengard & Sauerborn56, any increase in disease occurrence can be due to multiple factors. The factors that are most important are not always easy to determine. For infectious mononucleosis for example, which is caused by EB herpesvirus and spreads from person to person by an oropharyngeal route, increasing ambient temperatures are thought to encourage higher than normal outdoor activity and social interactions30, which may then increase virus transmission. Similarly, the range of diseases encompassed in this study is likely to be affected by multiple factors, amongst which any NAO variation may act directly on the pathogen or indirectly on the transmission cycle.

Our findings confirm that NAO conditions could have significant implications for European public health. The statistical influences of NAO conditions on outbreak occurrence concern all types of transmission routes: air-borne, water-borne, vector-borne and food-borne. We also showed that increases in outbreak occurrences over the last 50 years for all the diseases investigated are largely related to improvements in disease detection and therefore better reporting. Alternative explanations for the increase are factors linked to disease (re)emergence, increasing urbanization, or immigration from endemic countries42, none of them have not been accounted for within this study. For a given disease, a threshold above which policy measures would be engaged could be defined taking into account the economic impact of outbreak occurrence for example. Our results suggest that NAO index may be useful for an early warning system (EWS) at the European regional level, although addition analyses on a selection of highly climate-sensitive diseases should be undertaken.

Methods

Disease outbreaks

Data on 2,058 outbreaks from 114 epidemic infectious diseases (ID) which occurred in 36 countries during the period 1950 to 2009 were extracted from the Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) database (www.gideononline.com). A disease outbreak was defined in GIDEON, following the definition of the World Health Organization, as the occurrence of cases of disease in excess of what would normally be expected in a defined community within the current study. GIDEON is a medical database that provides continually updated data on the regional presence and epidemic status of pathogens and it has been used in various recent studies36,37,38. Records are updated in the GIDEON database using various sources such as WHO and Promed. A subset of 13 infectious diseases was subsequently selected from GIDEON (Table 1), based on whether they had been detected since the early to mid-1950s and thus sufficient data with which to undertake statistical analysis (i.e. from 1950 to 2009).

Health expenditure was added as a confounding variable to describe any increase in spending on health with time and a likely intensification in surveillance detection and outbreak reporting. This information was obtained from the Total Economy Database (www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/). TED was developed by the Groningen Growth and Development Centre at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands). The aggregated per capita GDP for Europe were used. Per capita health expenditure was obtained from the OECD (http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/, http://www.cesifo-group.de). Data on GDP, health expenditure and diseases was acquired for 36 countries.

The number of reported outbreaks of infectious diseases increased from 1950 to 2008 in Europe, as did the number of European countries presenting at least one outbreak of the diseases investigated (Fig. 1A and B). There were marked increasing trends in both the number of outbreaks and number of countries with outbreaks occurring since the early 1960s as well as an increase in health expenditure (Fig. 1C); statistical analyses were consequently undertaken for the period from 1960 to 2008.

North Atlantic Oscillation

Data on the NAO's monthly values were obtained from the National Weather Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov). The mean value of NAO per year was not correlated to year (Adjusted R2 = 0.02, F1,47 = 2.046, P = 0.16).

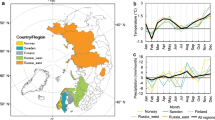

As NAO's values varied greatly according to season (and month) and northern and central or southern Europe (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/pna/nao.shtml), the countries within Europe were re-classified as northern European (including Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greenland, Hungary, Iceland, Republic of Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine and United Kingdom) and southern European (including Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Macedonia, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovenia and Spain).

Statistical analysis

In order to minimize any confounding influence of increased surveillance within some countries, which is likely to be related to health expenditure, we used a cubic smoothing spline as a detrending method for the long-term series of outbreaks using the function smooth.spline in the R 2.10 statistical package (http://www.R-project.org). The residuals of the trend were calculated by subtracting the value of the trend line from the original value.

We performed Generalized Linear Modelling (GLM) using R 2.1049 to identify the likely variables that may explain outbreaks (using detrended values) for each of the selected infectious diseases (ID). Each monthly NAO of the year or of the previous year (one year lag) was included in the model. Best models were selected using a backward-stepwise procedure with reduction in the AIC criterion and Bonferonni corrections were applied due to the use of multiple tests. Analyses were undertaken respectively for northern and southern European countries in order to take into account the differential influences of the NAO on European regions (www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov).

References

Lafferty, K. D. The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology 90, 888–900 (2009).

Epstein, P. The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases: comment. Ecology 91, 925–928 (2010).

Semenza, J. C. & Menne, B. Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 365–375 (2009).

McMichael, A. J., Woodruff, R. E. & Hales, S. Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet 367, 859–869 (2006).

Senior, K. Climate change and infectious disease: a dangerous liaison? Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, 92–93 (2008).

Baylis, M., Mellor, P. S. & Meiswinkel, R. Horse sickness and ENSO in South Africa. Nature 397, 574 (1999).

Paz, S., Bisharat, N., Paz, E., Kidar, O. & Cohen, D. Climate change and the emergence of Vibrio vulnificus disease in Israel. Environ. Res. 103, 390–396 (2007).

Pascual, M., Cazelles, B., Bouma, M. J., Chaves, L. F. & Koelle, K. Shifting patterns: Malaria dynamics and rainfall variability in an African highland. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 275, 123–132 (2008).

Epstein, P. Climate change and infectious disease: stormy weather ahead. Epidemiology 13, 373–375 (2002).

Bouma, J. M. & Dye, C. Cycles of malaria associated with El Niño in Venezuela. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 278, 1772–1774 (1997).

Cazelles, B., Chavez, M., McMichael, A. J. & Hales, S. Nonstationary influence of El Nino on the synchronous dengue epidemics in Thailand. PLoS Med. 2, 313–318 (2005).

Franke, C. R., Ziller, M., Staubach, C. & Latif, M. Impact of El Niño/Southern Oscillation on visceral leishmaniasis, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 914–917 (2002).

Gagnon, A. S., Bush, A. B. G. & Smoyer-Tomic, K. E. Dengue epidemics and the El Nino Southern Oscillation. Climate Res. 19, 35–43 (2001).

Gagnon, A. S., Smoyer-Tomic, K. E. & Bush, A. B. G. The El Nino Southern Oscillation and malaria epidemics in South America. Int. J. Biometeorol. 46, 81–89 (2002).

Hales, S., Weinstein, P., Souares, Y. & Woodward, A. El Niño and the dynamics of vectorborne disease transmission. Envir. Health Perspect. 107, 99–102 (1999).

Jones, A. E., Wort, U. U., Morse, A. P., Hastings, I. M. & Gagnon, A. S. Climate prediction of El Nino malaria epidemics in north-west Tanzania. Malaria J. 6 (2007).

Ling, H. Y. et al. Climate variability and increase in intensity and magnitude of dengue incidence in Singapore. Global Health Action. DOI: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.2036 (2009).

Linthicum, K. J. et al. Climate and satellite indicators to forecast Rift Valley fever epidemics in Kenya. Science 285, 397–400 (1999).

Nicholls, N. A method for predicting Murray Valley encephalitis in southeast Australia using the Southern Oscillation. Aus. J. Exp .Biol. Med. Sci. 64, 587–594 (1986).

Nicholls, N. El Nino-southern oscillation and vector-borne disease. Lancet 342, 1284–1285 (1993).

Zhou, G., Minakawa, N., Githeko, A. K. & Yan, G. Association between climate variability and malaria epidemics in the East African highlands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2375–2380 (2004).

Checkley, W. et al. Effects of El Niño and ambient temperature on hospital admissions for diarrhoeal diseases in Peruvian children. Lancet 355, 442–450 (1997).

Pascual, M., Rodó, X., Ellner, S., Colwell, R. & Bouma, M. Cholera dynamics and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Science 289, 1766–1769 (2000).

Hubálek, Z., Halouzka, J. & Juricová, Z. Longitudinal surveillance of the tick Ixodes ricinius for borreliae. Med. Vet; Entomol. 17, 46–51 (2003).

Rydén, P., Sjöstedt, A. & Johansson, A. Effects of climate change on tularaemia disease activity in Sweden. Global Health Action. DOI: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.2063 (2009).

Lima, M. A link between the North Atlantic Oscillation and measles dynamics during the vaccination period in England and Wales. Ecol. Let. 12, 302–314 (2009).

Purse, B. V. et al. Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3, 171–181 (2005).

Gale, P., Drew, T., Phipps, L. P., David, G. & Wooldridge, M. The effect of climate change on the occurrence and prevalence of livestock diseases in Great Britain: a review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106, 1409–1423 (2009).

McIntyre, K. M. et al. Impact of climate change on human and animal health. Vet. Record, 586 (2010).

Hubálek, Z. North Atlantic weather oscillation and human infectious diseases in the Czech Republic, 1951–2003. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 20, 263–272 (2005).

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269, 676–679 (1995).

Visbeck, M. H., Hurrell, J. W., Polvani, L. & Cullen, H. M. The North Atlantic Oscillation: Past, present and future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12876–12877 (2001).

Lionello, P. & Sanna, A. Mediterranean wave climate variability and its links with NAO and Indian Monsoon. Climate Dynamics 25, 611–623 (2005).

Engelthaler, D. et al. Climatic and environmental patterns associated with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Four corners region, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5, 87–94 (1999).

Tersagoa, K. et al. Hantavirus disease (nephropathia epidemica) in Belgium: effects of tree seed production and climate. Epidemiol Infec 137, 250–256 (2009).

Guernier, V., Hochberg, M. E. & Guégan, J.-F. Ecology drives the worldwide distribution of human diseases. PLoS Biol. 2, 740–746 (2004).

Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R. & Schaller, M. Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 275, 1279–1285 (2008).

Smith, K. F., Sax, D. F., Gaines, S. D., Guernier, V. & Guégan, J.-F. Globalization of human infectious disease. Ecology 88, 1903–1910 (2007).

Nascimento-Carvalho, C. M. et al. Seasonal patterns of viral and bacterial infections among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in a tropical region. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 42, 839–844 (2010).

Koeck, J. L. et al. Outbreak of aseptic meningitis in Djibouti in the aftermath of El Niño. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97, 526–527 (2003).

Wilson, N., Lush, D. & Baker, M. G. Meteorological and climate change themes at the 2010 International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases. Eurosurveillance 15, 5 (2010).

Ríos, M., García, J. M., Sánchez, J. A. & Pérez, D. A statistical analysis of the seasonality in pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 483–488 (2000).

Lipp, E. K. et al. The effect of seasonal variability and weather on microbial fecal pollution and enteric pathogens in a subtropical estuary. Estuaries 24, 266–276 (2001).

Hashizume, M. et al. Rotavirus infections and climate variability in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a time-series analysis. Epidemiol. Infect. 136, 1281–1289 (2008).

Rose, J. B. et al. Climate variability and change in the United States: Potential impacts on water and foodborne diseases caused by microbiologic agents. Environ. Health Perspectives 10, 211–221 (2001).

Hu, W., McMichael, A. J. & Tong, S. El Niño Southern Oscillation and the transmission of hepatitis A virus in Australia. Med. J. Australia 180, 487–488 (2004).

Kovats, S. R. et al. Climate variability and campylobacter infection: an international study. Int. J. Biometeorology 49, 207–214 (2005).

Greer, A., Ng, V. & Fisman, D. Climate change and infectious diseases in North America: the road ahead. CMAJ 178, 715–722 (2008).

Choi, K. M., Christakos, G. & Wilson, M. L. El Niño effects on influenza mortality risks in the state of California. Public Health 120, 505–516 (2006).

Sultan, B., Labadi, K., Guégan, J. & Janicot, S. Climate drives the meningitis epidemics onset in West Africa. PLoS Med. 2, e6 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Bi, P., Wang, G. & Hiller, J. El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and dysentery in Shandong province, China. Environ. Res. 103, 117 (2007).

Palo, T., Ahlm, C. & Tärnvik, A. Climate variability reveals complex events for tularemia dynamics in man and mammals. Ecol. Soc. 10, 22–29 (2005).

Svensson, K. et al. Landscape epidemiology of tularemia outbreaks in Sweden. Emerg. Infect. Dis. [serial on the Internet] (2009).

Greer, A., Ng, V. & Fisman, D. Climate change and infectious diseases in North America: the road ahead CMAJ. 178, 715–22 (2008).

Randolph, S. E. Tick-borne encephalitis virus, ticks and humans: short-term and long-term dynamics. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 462–467 (2008).

Evengard, B. & Sauerborn, R. Climate change influences infectious diseases both in the Arctic and the tropics: joining the dots. Global Health Action. DOI: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.2106 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was part of ENHanCE project (http://www.liv.ac.uk/enhance/) funded under the ERA EnvHealth scheme by NERC (grant number NE/G002827/1, http://www.nerc.ac.uk/) and ANSES (http://www.anses.fr/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. conceived the study and drafted the paper, S.M. and K.O. gathered and analyzed the data and A.W.-S., K.M.M. and M.B. helped to interpret results and contributed to the writing.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Morand, S., Owers, K., Waret-Szkuta, A. et al. Climate variability and outbreaks of infectious diseases in Europe. Sci Rep 3, 1774 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01774

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01774

This article is cited by

-

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) cases are not random: explaining trend, low- and high-frequency oscillations based on the Austrian TBE time series

BMC Infectious Diseases (2020)

-

Ebola spillover correlates with bat diversity

European Journal of Wildlife Research (2020)

-

Scrub typhus ecology: a systematic review of Orientia in vectors and hosts

Parasites & Vectors (2019)

-

Pathogen adaptation to temperature with density dependent host mortality and climate change

Modeling Earth Systems and Environment (2019)

-

Individualistic values are related to an increase in the outbreaks of infectious diseases and zoonotic diseases

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.