Abstract

It was claimed that the incident light can be gradually slowed down and finally trapped in a tapered metamaterial waveguide. Here we show that the energy incident from the input port of the tapered metamaterial waveguide will be totally reflected (instead of being trapped) due to the strong intermodal coupling between the forward and backward modes. The underlying physical mechanism for this strong intermodal-coupling is given. The occurrence of energy reflection is unambiguously proved using several independent methods, (1) the semi-analytical mode matching technique, (2) the numerical finite element simulation, (3) the requirement of energy and momentum conservation and (4) an experimental verification at microwave frequency. The dream of ‘trapped rainbow’ for storage of light might still be possible if this intermodal coupling could be blocked and our study provides a useful guidance for such an endeavor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Negative refractive index metamaterials1,2 with simultaneous negative permittivity and negative permeability (also called left-handed materials; LHM) open new avenues to achieve unprecedented physical properties and functionality unattainable with naturally occurring materials3,4. Inside a left-handed material, the wave vector and energy flow are in opposite directions. By virtue of this unique property, a metamaterial slab waveguide consisting of left-handed material core (or cladding) and right-handed material (RHM; i.e., conventional dielectric) cladding (or core) are capable of slowing down drastically the velocity of light propagation, even to zero velocity5,6. This fascinating property is attractive for light storage, light buffer, etc, which are indispensable components for all optical signal processing7.

In this paper we will reveal the truth about ‘trapped rainbow’ storage of light: the complete standstill of light at the critical thickness is impossible due to the strong intermodal coupling between two nearly degenerated modes. Several independent methods are employed to prove definitely the occurrence of energy reflection. We use the mode matching technique8,9 to prove the total energy reflection, as well as the finite element simulation. This reflection can also be attributed to the requirement of the energy and momentum conservation. Finally, the strong reflection is verified experimentally by observing the strong near-field electromagnetic wave modulation in a tapered spoof plasmon waveguide.

Results

Mode degeneracy, intermodal coupling and reflection

Fig. 1a and b show the propagation constant β and energy flow (group) velocity vE as a function of the core-thickness d for our metamaterial slab waveguide (see the inset in Fig. 1a). If we take a closer look at Fig. 1a, it is easy to find two modes with distinct properties coexist for a certain core layer thickness: the forward mode, whose energy flow and wave vector are in the same direction; and the backward mode, whose energy flow and wave vector are in opposite directions (e.g., the lower and upper branches of the fundamental oscillating TM2 mode in Fig. 1a). The propagation constants of a forward mode and backward mode degenerate, i.e., βf = βb at the critical core thickness (denoted by dc; see Fig. 1a below), which result in zero propagation velocity at this critical location (Fig. 1b). Since light waves at different frequencies have different critical thickness for achieving zero velocity, ‘trapped rainbow’ storage of light was claimed to be feasible in a tapered metamaterial waveguide5 or plamonic graded structures10. Here one sees clearly that the presence of the critical core thickness dc gives rise to two regions, the free propagation region (d>dc) and the attenuation region (d<dc). The critical thickness dc is calculated to be 52.451813091371 μm for fundamental oscillating TM2 mode at 1 THz (free space wavelength λc = 300 μm). A forward guided mode has more energy confined in the RHM cladding, while a backward guided mode has more energy confined in the metamaterial core layer (see the inset for point O1 in Fig. 1c). Since the cladding layer and the core layer have opposite energy flow, the overall energy flow highly depends on the core layer thickness (see Fig. 1b). At the critical thickness, the counter-directional energy flows balance each other and result in a slow waveguide with zero group velocity.

Analysis of forward and backward TM2 modes as the core thickness (d) of a metamaterial slab waveguide varies.

(a) The propagation constants of the forward and backward TM2 modes (at the frequency of 1 THz) as d varies. (b) Energy flow velocity vE as core thickness d varies. For a waveguide mode, the energy flow velocity is defined as the ratio of the integrated Poynting vector to the integrated energy density. (c) Overlap of the forward and backward guided modes as core thickness d varies. The mode overlap is defined as  , where Hf (in pink color) and Hb (in aquamarine blue) denote Hy components of the forward and backward modes, respectively. Inset: mode profiles of Hf and Hb for two different core thicknesses, namely, d = 54.7 μm at point O1 and d = 52.7 μm at point O2 (very close to critical thickness dc ≈ 52.45 μm).

, where Hf (in pink color) and Hb (in aquamarine blue) denote Hy components of the forward and backward modes, respectively. Inset: mode profiles of Hf and Hb for two different core thicknesses, namely, d = 54.7 μm at point O1 and d = 52.7 μm at point O2 (very close to critical thickness dc ≈ 52.45 μm).

Consider a waveguide with a continuously tapered core layer thickness and assume an incident forward mode is excited from the left port (see Fig. 2). It is noted that the backward guided mode has negative group velocity but positive wave vector, which is in the same direction as the wave vector of the incident forward guided mode. As d approaches dc, the incident right-going forward mode (see point Mf on the lower branch in Fig. 1a) and the left-going backward mode (see point Mb on the upper branch of the same order in Fig. 1a) get similar wave vectors (the same direction and the similar magnitude). In the meanwhile, the modal profiles of the backward and forward modes become perfectly overlapped (see the overlap curve in Fig. 1c) as d approaches dc (see the inset for point O2in Fig. 1c). When these two requirements are satisfied, the coupling between forward and backward modes is likely to occur, as long as some small spatial perturbation exists along the waveguide (e.g., the tapering of the waveguide).

Reflection from a tapered metamaterial waveguide.

(a) Reflection and transmission of different modes for the case of dout < dc. The thick open arrows show the direction of the energy flow, while the thin arrows inside the thick open arrows indicate the direction of wave vector. (b) Optical power ratio for each mode of reflection or leakage, as the total number of steps increases. Here we choose din = 55 μm, dout = 52.4 μm (<dc). The waveguide is linearly tapered and the length of the tapered section is Ltaper = 20 λc. (c) Another waveguide with output port core layer thickness dout > dc. (d) Accumulated contribution to the reflection and transmission from segment [0, z] of the whole tapered waveguide with dout > dc. R12 keeps growing and T11 keeps decreasing as z increases. R11 is absent in this situation since the tapered waveguide has been smoothly approximated using a sufficient number of steps. The length of the tapered waveguide is 50 λc. Here we choose din = 55 μm and dgap(z) = (d(z)−dc)×10−kz (i.e., the tapering of this waveguide becomes slower and slower as z increases, see the inset of fig. 2d), where tapering coefficient k = 7.3×10−4/μm.

The mode matching technique is then employed to quantitatively describe the intermodal coupling behavior between the forward and backward modes inside a tapered waveguide (the detailed mode matching calculation can be found in Supplementary Materials). A series of steps is used to approximate the tapered boundary. As long as the number of steps is sufficiently large, these steps can resemble the originally smooth boundary and thus produce a precise and reliable calculation result. The field components at a specified location are expressed using the superposition of local eigenmodes at this locally flat waveguide. After matching the tangential field components along the interfaces of neighboring flat waveguide, a scattering matrix relating the reflected field and transmitted field to the incident field can be derived. Then the reflection and transmission in response to the stimulus of incoming forward mode is obtained in a semi-analytical way.

In our study, we consider the case when the core-thickness d is not large so that only one oscillating mode, namely, TM2 mode, can be supported in the metamaterial waveguide (The case for a thicker core layer and the consequent appearance of high order oscillating mode are considered in the Supplementary Materials). Here we calculate the reflection of optical power on two kinds of tapered waveguides with the same core layer thickness at the input port (din = 55 μm) but different core layer thickness at the output port (dout): (i), dout < dc; (ii), dout > dc.

For the waveguide with dout < dc (here dout = 52.4 μm ≈ dc−0.05 μm), the output waveguide cannot support any guided mode and consequently no transmission is expected. We approximate the tapered structure with many steps and increase the total number of steps N to approach a smoothly tapered waveguide (see Fig. 2a). The incident optical power carried by a forward mode in the input waveguide will be channeled to different modes after it enters the tapered waveguide. The exact ratio of the optical power in each mode, which is obtained from our mode matching calculation, is shown in Fig. 2b. In particular, we are interested in the following power flow channels (see the colored arrows in Fig. 2a): R11 (conventional reflection from the incident right-going forward mode to the left-going forward mode), R12 (reflection due to the coupling from the incident forward mode on the lower branch to the backward mode on the upper branch, see the red open arrow in the inset of Fig. 2a) and the power scattered to leaky modes. Our calculation results of Fig. 2b show that, (1) when the number of steps N is small (~10), the optical power scattered into leaky modes is observable. However, it deceases quickly as the tapered waveguide becomes smoother and smoother (N>20); (2) when N is small, R11 is comparable with R12. However, R11 also deceases to nearly zero as the tapered waveguide becomes smoother and smoother (N>60); (3) for a sufficiently smooth waveguide, R12 is precisely unity, which indicates that all the energy of the incident forward mode will be eventually coupled to the left-going backward mode and flow out from the input port.

The above calculation results indicate that the sudden transition of wave vector (βf to -βf) is unlikely to occur in a slowly tapered waveguide, while the transition/coupling of similar wave vectors (βf to βb) is much more preferable due to the intrinsic degeneracy of βf and βb modes at the critical thickness. Both the wave vectors and the modal profiles are exactly the same at the critical thickness dc for the specified wavelength λc. This can also be understood as follows. The slow tapering can be considered as a sort of small perturbation so that the wave vector should vary bit by bit. For example, for a periodic grating with a period Λ for small refractive index change, the wave vector of the scattered field can be changed by 2π/Λ due to the phase matching condition. If the period Λ is very large (very small inhomogenity), then 2π/Λ becomes very small and thus the change in the wave vector should also be small, i.e., the wave vector will remain the same direction (though the magnitude will be changed slightly). Thus we should expect similar behavior of wave vector in our slowly tapered waveguide. Only the coupling between modes with similar wave vector is likely to occur in a slowly tapered metamaterial waveguide and the coupling between two nearly degenerated modes is inevitable even the tapering of the waveguide is extremely slow. A tiny perturbation (tapering) will lead to strong intermodal coupling between these two modes. This is the underlying mechanism for the reflection of the incident energy in a tapered metamaterial waveguide.

Next we turn to the case of dout > dc (here dout = dc + 10−3 μm). In contrast to the previous case, the output waveguide still supports some guided modes in this situation (see Fig. 2c). In order to clarify the contribution of each slice of the tapered waveguide to the energy reflection, we introduce the concept of invariant imbedding11 into this structure. Specifically, we choose two cross sections perpendicular to the z axis in the tapered waveguide, denoted by Plane A (z = z1) and Plane B (z = z2). The segment sandwiched between Plane A and Plane B will contribute to a certain amount of reflection, which can also be calculated exactly by applying the mode matching method on this specific segment. By varying z1 or z2, we can calculate r12 (z1, z2), r11 (z1, z2) and t12 (z1, z2), where rij or tij represent the field component reflection or transmission of the j mode under the excitation of the i mode. For example, r12 (0, 20 λc) is the reflection for the whole tapered waveguide while r12 (0, z) tells the accumulated contribution from the segment in the interval [0, z] of the whole tapered waveguide. The reflection and transmission of incident energy can be obtained simply by Rij = |rij|2, Tij = |tij|2, where i,j = 1,2.

Fig. 2d shows the calculated R12 (0, z) (accumulated contribution to reflection R12 from the coupling in the interval [0, z] of the whole tapered waveguide) and T11(0, z) as a function of z. From Fig. 2d one sees that more and more incident optical power is reflected as z increases, until the reflection approaches unity. The starting segment [where dgap (≡ d − dc) is large (1 or 2 μm)] of the tapered waveguide contributes little to the reflection. However, significantly reflection arises at the segment where dgap approaches 0 (i.e., when d is close to the critical thickness).

From the mode matching calculation results, we can conclude that a significant amount of the incident energy carried by a forward mode will couple to the backward mode BEFORE the group velocity decreases to exactly zero. Strong intermodal coupling of forward mode and backward mode occurs for a tapered waveguide with an output port whose core thickness is close enough to the critical thickness. It is the similarities in the wave vectors and modal profiles of the two nearly degenerated modes at the segment where the core thickness is close to (but still slightly larger than) dc that lead to considerable energy reversal.

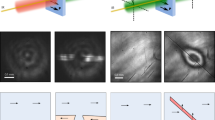

The field distributions inside tapered waveguides of different output ports, especially the local field enhancement around the critical thickness are shown in Fig. 3. The first waveguide has an output port with core layer thickness slightly smaller than dc (dout = 52.4 μm ≈dc − 0.05 μm), while the second waveguide has an output port with core layer thickness larger than dc (dout = dc + 10−3 μm). The ultra-small difference of the two output ports leads to distinct behavior of local field distributions around the critical thickness. In the first waveguide, the propagation constant of the output port becomes a complex one and thus the field is exponentially attenuated at the output segment. On the contrary, the output port of the second waveguide can still support guided wave. As can be seen from Fig. 3c and d, the optical field magnitude is enhanced by approximately 4 times in a large area (however, the transmitted energy flow has a vanished value since the integrated Poynting vector is ultra-small at the output port with nearly zero energy velocity). This property is highly encouraging for applications related to enhanced light-matter interaction. Here we also note the following intrinsic property of a slow light waveguide: the energy flow may be ultra-small at a location where the energy velocity is nearly zero even though the field intensity may be quite large there.

Local field enhancement around the critical thickness due to slow light effect.

The linearly tapered section locates between z = 0 and z = 6000 μm for both waveguides. (a) and (b) The core thicknesses of the input and output waveguides are 55 μm and 52.4 μm, respectively. (a) Distribution of field magnitude |Hy| calculated with the mode matching technique. (b) The plots of |Hy| (normalized to the incident field) along line z = 0 calculated using two different methods. The FEM simulation (commercial software COMSOL) gives exactly the same field distribution as the calculated result of the mode matching technique, which shows the reliability of our results calculated with the mode matching technique. In the FEM simulation, an adiabatic scalar absorbing layer20 is used to eliminate parasitic reflection. The profile of launching source has been specified to ensure the purely excitation of the forward mode. In (c) and (d) the same quantity as in (a) and (b) is shown for another tapered waveguide whose core thicknesses of the input and output waveguides are 55 μm and (dc+10−3 μm), respectively. A factor of 4 for the local field enhancement (near the critical core thickness) is observed due to the slow light effect.

We would like to emphasis that, the local field is greatly enhanced around the critical thickness due to the slow light effect, but light cannot be trapped and stay standstill at the critical thickness. In Fig. 3, we observe clearly standing-wave characteristics in both waveguides for field magnitude |Hy| (normalized with the incident field magnitude), with alternative peaks and nodes along the z direction (Slow waves in a flat slab waveguide with grading refractive index exhibits similar standing-wave characteristics, which indicates the occurrence of intermodal coupling. The detail calculation can be found in Supplementary Materials. This additional calculation shows that the reflection is due to the physical intermodal coupling, rather than the inexact numerical modeling of the tapered boundary). This is a straightforward evidence for the occurrence of intermodal coupling induced backward mode: the backward mode and forward mode interfere coherently with each other, forming alternative peaks and nodes of the field magnitude. If we assume that the trapping of incident energy can truly occur, the field at the critical thickness should be infinitely large since the energy will keep increasing at the critical thickness region due to the continuous transportation of energy from the incident port. Thus the finite enhancement (about 4 times) of the field also indicates the breakdown of light trapping.

Tsakmakidis et al. claimed in5 that a tapered metamaterial waveguide could lead to a complete standstill of light at the critical core thickness. Their theoretical conclusion is based on the application of adiabatic approximation method. To ensure the reliability of the adiabatic approximation method, the variation of core thickness d along the propagation direction z [i.e., z derivative of d(x)] has to fulfill the following condition12

where βi and βjstand for the propagation constants of an arbitrary pair of modes in the slab waveguide. Since the forward mode and backward mode degenerate at the critical thickness dc, the right side of equation (1) can be infinitesimal and consequently the adiabatic approximation becomes inapplicable for dealing with systems containing degenerating modes (e.g., the degeneracy of forward mode and backward mode in our tapered waveguide structure).

Intermodal coupling and reflection in time domain

It is noted that all the above results are calculated in frequency domain (for a single frequency of 1 THz). In order to show the slow light effect and intermodal coupling effect in a straightforward way, it is necessary to exhibit the propagation of a wave packet in time domain.

Here we form a guided wave packet through the superposition of 100 wavelengths with a central wavelength of 300 μm (i.e., 1 THz). Their amplitudes are modulated by a Gaussian function (see Fig. 4a). The spatial profile of this wave packet inside the input segment is shown in Fig. 4b. Through the superposition of the calculated field inside the whole tapered waveguide for all the spectral components, the propagation of the wave packet in time domain is obtained.

Propagation and reflection of a guided wave packet in time domain in a tapered slow light metamaterial waveguide.

(a) Components of 100 wavelengths (frequencies) used to construct the guided wave packet in time domain. (b) The spatial distribution of the field magnitude of the wave packet in the input waveguide. (c) The peak location of field magnitude |Hy| at different instants (in unit of wavelength after multiplying with light speed c in free space). Since several peaks exist inside the waveguide, two peaks with comparable amplitudes may cause some sudden transition of the peak location in (c) if the smaller peak becomes larger than the other peak of the double peaks. (d)–(h) The field pattern of |Hy| at different times after the wave packet enters the tapered slow light waveguide. The mode matching method is used in the calculation for each frequency component. The core thicknesses for the input port and output port of this waveguide are fixed to 55 μm and 52.2 μm, respectively. The length of the tapered section is 40 λc.

Fig. 4c shows the trajectory of the wave packet center inside the tapered waveguide. The instantaneous snaps of magnetic field |Hy| at 5 temporal slices are shown in Fig. 4(d–h). As the wave packet propagates into the tapered section, the spatial width of the packet gets compressed while the amplitude of the wave packet grows (see Fig. 4f). However, the pulse cannot be frozen at this location forever to form a ‘trapped rainbow’ (a dream described in [5] that light of different frequencies will be trapped to a complete standstill at different locations of critical thickness). The packet will eventually propagate backward after a relatively long period due to the intermodal coupling mechanism (Fig. 4f, g and h). It should be noted that the incident forward wave packet is loosely confined in lateral direction in Fig. 4d. In comparison, the reflected backward wave packet is tightly confined (see Fig. 4h). This modal confinement contrast serves as another evidence of considerable coupling of incident energy into backward mode. Thus we conclude that a wave packet can genuinely be slowed down for quite a while using this tapered waveguide structure, but a complete standstill is impossible. Similar results for a lossy case are given in Supplementary Information, as well as some animations showing the reflection process of the wave packet in both the lossless and lossy cases. The simulation result for the case of a lossy metamaterial waveguide (Fig. S5 and the animation on the wave packet movement in the supporting material) can also support our intermodal coupling mechanism and conclusion.

Analysis based on energy conservation and momentum conservation

Above we have studied the reflection of the incident energy in the tapered metamaterial waveguide numerically and semi-analytically through the intermodal coupling mechanism. Below we show that the reflection is actually a natural requirement of energy conservation and momentum conservation.

The total momentum of optical wave in a medium is composed of two parts, the electromagnetic momentum and the mechanical momentum13,14. Since metamaterial is intrinsically dispersive, the momentum carried by an electromagnetic wave in a metamaterial has to be treated in a time-causal way. Thus it is necessary to construct a wave packet and study the amount of momentum (both the electromagnetic part and mechanical part) picked up by this wave packet during its propagation14. The momentum flow of the electromagnetic wave along its propagation direction is the amount of overall momentum per unit time. Using such a formulism, we can obtain an analytical formula for the momentum flow of guided waves in a slow light waveguide of uniform core layer thickness [see eq. (S17) in the Supplementary Materials].

Fig. 5a shows the momentum flow Pz (the z direction momentum flow across the lateral cross-section for a specific guided mode) of guided modes in a uniform waveguide as the core layer thicknesses varies. It is worthwhile to define a dimensionless quantity η ≡ c·Pz/Sz for the guided wave, where Sz is the corresponding energy flow and c is the light speed in vacuum. It is somewhat counter-intuitive that Pz remains finite at the critical thickness (Fig. 5a), although Sz has vanished at this thickness, which leads to a divergence of the dimensionless quantity η at the critical thickness (Fig. 5b).

Momentum flow inside a uniform metamaterial waveguide as the core layer thicknesses varies.

(a) Momentum flow |Pz| (normalized to the magnetic field at x = 0) inside uniform waveguide structures versus the variation of core thicknesses d. (b) Dimensionless quantity η versus the variation of core layer thickness d. It is noted that η diverges when d approaches dc.

Now we can derive the reflection and transmission based on the conservation laws of the energy and momentum. Since our metamaterial waveguide is adiabatically tapered, the wave vector must change bit by bit. Thus only three waveguide modes with similar wave vector are required to be taken into account for the conservation calculation, namely, the incident forward mode  , the coupled backward mode

, the coupled backward mode  and the transmitted forward mode

and the transmitted forward mode  . In a time-harmonic system, the incoming and outgoing energy flows should cancel each other, as well as the incoming and outgoing momentum flows.

. In a time-harmonic system, the incoming and outgoing energy flows should cancel each other, as well as the incoming and outgoing momentum flows.

In our tapering waveguide structure, we choose a region enclosing the tapering section for our conservation study. Assuming a unity energy flow is carried by the incident forward mode at the input port, we can obtain the following energy flow balance and momentum flow balance equations for the energy reflection R at the input port and the energy transmission T at the output port,

Here,  ,

,  and

and  represent the dimensionless quantity η (defined earlier) for the incident forward mode, the coupled backward mode and the transmitted forward mode, respectively and δ is a finite quantity representing the z direction force suffered by the waveguide itself due to the tapering boundary. In eq. (2) or (3), the left hand side is for the incoming amount of energy or momentum, while the right hand side is for the outgoing amount of energy or momentum. After a simple calculation, we obtain

represent the dimensionless quantity η (defined earlier) for the incident forward mode, the coupled backward mode and the transmitted forward mode, respectively and δ is a finite quantity representing the z direction force suffered by the waveguide itself due to the tapering boundary. In eq. (2) or (3), the left hand side is for the incoming amount of energy or momentum, while the right hand side is for the outgoing amount of energy or momentum. After a simple calculation, we obtain

From the above two equations, we can obtain total reflection and zero transmission if the input core layer thickness is relative far from dc and the output core layer thickness is very close to dc (i.e.,  ; for instance, the case in Fig. 2c, d), as

; for instance, the case in Fig. 2c, d), as  becomes singular (see Fig. 5b) while

becomes singular (see Fig. 5b) while  and

and  are finite. Note that partial reflection and partial transmission may occur only if both din and dout are comparable and larger than dc [i.e.,

are finite. Note that partial reflection and partial transmission may occur only if both din and dout are comparable and larger than dc [i.e.,  and

and  are comparable; e.g., the case in our invariant embedding calculation when the core layer thickness of the output port is also relatively far from (larger than) dc]. As expected, total transmission and zero reflection can be deduced from eq. (4) and eq. (5) for a waveguide without tapering, since

are comparable; e.g., the case in our invariant embedding calculation when the core layer thickness of the output port is also relatively far from (larger than) dc]. As expected, total transmission and zero reflection can be deduced from eq. (4) and eq. (5) for a waveguide without tapering, since  and δ = 0 for a uniform waveguide. The tapered metamaterial waveguide will give total reflection and zero transmission if the output core thickness is smaller than dc, as no tunneling is expected at the output port (waves are exponentially attenuated in the output waveguide).

and δ = 0 for a uniform waveguide. The tapered metamaterial waveguide will give total reflection and zero transmission if the output core thickness is smaller than dc, as no tunneling is expected at the output port (waves are exponentially attenuated in the output waveguide).

Therefore, based on a purely analytical analysis utilizing the fundamental laws of energy conservation and momentum conservation, we can obtain a conclusion on energy reflection similar to Fig. 2. These analytical results confirm our intermodal coupling mechanism in a slowly-tapered slow light waveguide and provide a unique insight into the physical interpretation of energy reflection in the metamaterial waveguide structure.

Experimental verification at microwave frequencies

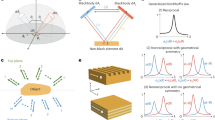

Finally, we would like to verify experimentally the intermodal coupling mechanism by investigating a tapered slow-wave structure at microwave frequencies (Fig. 6a).

Experimental setup and results.

(a) Photograph of our experimental setup. (b) The unit cell for the structure of etched grooves on copper with the following parameters: period g = 3, groove width a = 2, lateral width w = 20, all in unit of mm. Groove depth is denoted by h. (c) Dispersion curves for such periodic structures with different groove depth h. The vertical green line indicates the location of Bloch boundary, where the group velocity is zero. The horizontal black line indicates the frequency of 9.2 GHz. The four points along the horizontal black line indicate four modes. The two in blue are of forward mode (denoted by Mf) and the other two in red (denoted by Mb) are of backward mode. (d) Power detected by the probe along the z direction at the center of the waveguide's surface. (e) Intensity modulation obtained by comparing the peak values and dip values of the detected signal at the specific region z∈[75, 100] (in unit of mm). The red line and green line show the intensity modulations of the experimental result and the simulation result (using the conductivity of real copper σ = 5.8×107 S·m−1), respectively.

The interface between a metal and a dielectric can support a conventional surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode15 at an optical frequency, but not at microwave frequencies due to metal's large permittivity at these frequencies. However, a SPP-like mode can be supported if periodic subwavelength grooves are fabricated on a metal's surface16.

In our experiment, the spoof plamson waveguide is similar to the recently proposed domino plasmon structure17, which is composed of periodic grooves etched on a metal's surface and the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 6a. Unit cell of this slow-wave structure is shown in Fig. 6b. Its period g and groove-width a are 3 mm and 2 mm, respectively. The lateral dimension w is 20 mm. In Fig. 6c one sees that the depth h of the groove will greatly influence the dispersion curve of spoof plasmon mode. The cutoff frequency decreases as the groove depth increases. Therefore, an electromagnetic wave with a specific frequency can be guided by such a structure with a shallow depth. As the groove depth increases, its group velocity will decrease gradually. Especially, the propagation velocity will approach zero when the depth of groove reaches a critical depth. At the region close to the critical depth, some forward mode and backward mode with nearly the same wave vectors coexist, as can be seen from the modes around the Bloch boundary at kg = π in Fig. 6c (forward mode in blue and backward mode in red). According to our intermodal coupling prediction, strong coupling between the forward mode and the backward mode will occur when their wave vectors get close to each other. This coupling mechanism will lead to an obvious reflection of the incident energy in a tapered slow light waveguide.

Now we would like to verify the coupling induced reflection using the above slow-wave structure with tapered groove depth (Fig. 6a). The waveguide can be divided into three segments based on the depth of the etched grooves. In the 1st segment, the groove depth h increases linearly from 3 mm to 8 mm in 50 periods; in the 2nd segment, h will remain constant (8 mm) for 30 periods; and in the last segment, h decreases linearly back to 3 mm also in 50 periods.

From the dispersion curves in Fig. 6c we see that the deepest groove depth h = 8 mm has a corresponding zero-velocity frequency fc = 8.44 GHz. The propagation of an incident electromagnetic wave with a frequency above fc will be slowed down gradually as the groove depth increases along the waveguide. In the end, it will encounter a region with groove depth close to the corresponding critical depth. At this critical region, the forward mode will be coupled strongly to some backward mode, leading to a significant amount of energy reflection. On the contrary, for an incident electromagnetic wave with frequency below fc, it can not only pass the 1st segment, but also go through the 2nd segment (which has the lowest cutoff frequency) and eventually reach the 3rd segment. The distinct behavior of some higher frequency and lower frequency waves can then be utilized to verify experimentally the intermodal coupling mechanism. By examining the field intensity variation due to the interference of the forward mode and backward mode, the amount of energy reflection can be estimated.

Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) is used for both the signal excitation and detection in our experimental setup (see Fig. 6a). A coaxial antenna is utilized to excite the guided mode in the waveguide. A probe is used to measure the electric field intensity at the surface of the spoof plasmon waveguide. If a significant amount of the incident energy is coupled to the backward mode, a strong intensity contrast at different locations along the propagation direction should be observed due to the standing wave arising from the interference of the incident wave and the reflected wave (similar to the field pattern in Fig. 3).

In Fig. 6d, we show the experimental result at 3 representative frequencies. For frequency above fc, we have observed significant intensity modulation (20 dB) at the surface of the 1st segment in our waveguide and very small signal intensity (<−40 dBm, indicating ultra-small transmitted wave) in the 2nd and the 3rd segments. This is a clear evidence of strong reflection arising from the backward mode coupling. In the meanwhile, the intensity modulation is less then 5dB for the frequency below fc along the whole waveguide. (This small intensity modulation is due to some small energy reflection at the far end of our waveguide.)

The reflection at different frequencies can be evaluated from the intensity modulation at the 1st segment. Here we choose the interval z ∈[75, 100], i.e., h ∈[75, 100] (in unit of mm) for evaluation of the intensity modulation. In this region, the near field effect of the excitation source is negligible and the electromagnetic fields have become purely guided wave. By comparing the peak values and dip values for each frequency, we obtain the intensity modulation shown in Fig. 6e (red line). There is an abrupt increase (more than 20 dB) in intensity modulation at the cutoff frequency fc, which indicates a strong coupling into backward mode and consequently a strong reflection (more than 80%) for waves of high frequency beyond fc. The blue line in Fig. 6e shows a simulation result obtained with CST (Finite Integral Method), which agrees well with our experiment result. Therefore, our experimental results verify the intermodal coupling mechanism in a tapered slow-light waveguide as we reveal in this paper.

Discussion

The coupling between the forward and backward modes is due to the special dispersion curve in Fig. 1a. If we can engineer the dispersion of a slow light waveguide in such a way that the upper branch of backward mode can be “mirror-imaged” (around the vertical axis passing the point of zero group velocity) to a left branch (of forward mode type), we would expect little reflection as long as the tapering is smooth enough. As an example to illustrate this, we have studied a tapered slow light photonic crystal waveguide which has a zero-group-velocity point on its dispersion band and the results of negligible reflection are shown in Supplementary Information. This also shows the reflection in a tapered slow light waveguide can be eliminated by engineering carefully the dispersion of the waveguide.

In summary, we have given a clear physical explanation why the previously reported ‘trapped rainbow’ waveguide5 cannot be used to trap light at the critical core thickness. We have shown both semi-analytically and numerically that energy reflection arising from intermodal coupling between two nearly-degenerated modes is inevitable, regardless how slow the metamaterial waveguide is tapered. This is completely different from a conventional case where an adiabatic tapering is typically used to avoid reflection. Furthermore, we have also proved analytically the energy reflection based on the fundamental laws of energy conservation and momentum conservation. Finally, the energy reflection has been verified experimentally from the measured modulation of the field intensity inside a tapered slow-wave waveguide at microwave frequencies.

Reze et al.18 and Tsakmakidis et al.19 have debated on the impact of a small loss of the metamaterial to the ‘trapped rainbow’. In fact, we have shown here that light cannot be trapped in such a tapered slow light metamaterial waveguide even if all the materials are lossless. Nevertheless, some slow light metamaterial (including photonic crystal) waveguides with carefully engineered dispersion can still have interesting potential applications, such as an efficient generator for backward-going backward wave, a tunable splitter to backward and forward waves and large field enhancement for some practical applications. “Trapped rainbow” for storage of light is still hopeful if we can find a smart way to block the coupling between the forward and backward modes in a slow light metamaterial waveguide.

Methods

In all our theoretical studies, the tapered waveguide has the following parameters: ε1 = μ1 = 1−ω2/(ωp2+iωΓ) (for the metamaterial core) with  , ωc/2π = 1 THz (corresponding to λc = 300 μm), ε2 = 2.56 (relative permittivity for lower cladding), μ2 = 1, ε3 = 2.25 (for upper cladding), μ3 = 1. The metamaterial is assumed to be lossless, i.e., Γ = 0 for simplicity. All the calculations are for TM polarized monochromatic continuous wave at the frequency of 1 THz except as otherwise specified.

, ωc/2π = 1 THz (corresponding to λc = 300 μm), ε2 = 2.56 (relative permittivity for lower cladding), μ2 = 1, ε3 = 2.25 (for upper cladding), μ3 = 1. The metamaterial is assumed to be lossless, i.e., Γ = 0 for simplicity. All the calculations are for TM polarized monochromatic continuous wave at the frequency of 1 THz except as otherwise specified.

Change history

28 February 2014

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Shelby, R. A., Smith, D. R. & Schultz, S. Experimental Verification of a Negative Index of Refraction. Science 292, 77–79 (2001).

Smith, D. R., Pendry, J. B. & Wiltshire, M. C. K. Metamaterials and Negative Refractive Index. Science 305, 788–792 (2004).

Pendry, J. B. Negative Refraction Makes a Perfect Lens. Physical Review Letters 85, 3966 (2000).

Pendry, J. B., Schurig, D. & Smith, D. R. Controlling Electromagnetic Fields. Science 312, 1780–1782 (2006).

Tsakmakidis, K. L., Boardman, A. D. & Hess, O. ‘Trapped rainbow' storage of light in metamaterials. Nature 450, 397–401 (2007).

He, J. & He, S. Slow propagation of electromagnetic waves in a dielectric slab waveguide with a left-handed material substrate. Microwave and Wireless Components Letters, IEEE 16, 96–98 (2006).

Krauss, T. F. Why do we need slow light? Nat Photon 2, 448–450 (2008).

Reiter, J. M. & Arndt, F. Rigorous analysis of arbitrarily shaped H- and E-plane discontinuities in rectangular waveguides by a full-wave boundary contour mode-matching method. Microwave Theory and Techniques, IEEE Transactions on 43, 796–801 (1995).

Kocabas, S. E., Veronis, G., Miller, D. A. B. & Fan, S. Modal analysis and coupling in metal-insulator-metal waveguides. Physical Review B (Condensed Matter and Materials Physics) 79, 035120–035117 (2009).

Gan, Q., Ding, Y. J. & Bartoli, F. J. ”Rainbow„ Trapping and Releasing at Telecommunication Wavelengths. Physical Review Letters 102, 056801–056804 (2009).

He, S. & Strom, S. The electromagnetic scattering problem in the time domain for a dissipative slab and a point source using invariant imbedding. Journal of Mathematical Physics 32, 3529–3539 (1991).

Snyder, A. & Love, J. D. Optical waveguide theory Ch. 19. (Chapman and Hall, 1983).

Yaghjian, A. D. Internal Energy, Q-Energy, Poynting's Theorem and the Stress Dyadic in Dispersive Material. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 55, 1495–1505 (2007).

He, Y., Shen, J. & He, S. Consistent formalism for the momentum of electromagnetic waves in lossless dispersive metamaterials and the conservation of momentum. Progress In Electromagnetics Research 116, 81–106 (2011).

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830 (2003).

Pendry, J. B., Martin-Moreno, L. & Garcia-Vidal, F. J. Mimicking Surface Plasmons with Structured Surfaces. Science 305, 847–848 (2004).

Martin-Cano, D. et al. Domino plasmons for subwavelengthterahertz circuitry. Opt. Express 18, 754–764 (2010).

Reza, A., Dignam, M. M. & Hughes, S. Can light be stopped in realistic metamaterials? Nature 455, E10–E11 (2008).

Tsakmakidis, K. L., Boardman, A. D. & Hess, O. Tsakmakidis et al. reply. Nature 455, E11–E12 (2008).

Loh, P.-R., Oskooi, A. F., Ibanescu, M., Skorobogatiy, M. & Johnson, S. G. Fundamental relation between phase and group velocity and application to the failure of perfectly matched layers in backward-wave structures. Phys. Rev. E 79, 065601 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jinlong He and Xiaocheng Ge for some help in computation and discussion. Yingran He would like to thank Prof. Yungui Ma and Dr. Shuomin Zhong for their help in the microwave experiment. This work is partially supported by the National Basic Research Program and National Natural Science Foundation of China (61178062 and 60990322), the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2010R50007), the Swedish Research Council (VR) and AOARD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. initiated the idea, supervised the finding of the present work and was responsible for scientific explanation for the finding. Y.R.H. performed the experiments and most of the computations. Y.J. contributed to the discussions and computational methods. S. H and Y. R. H. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

animation 1

Supplementary Information

animation 2

Supplementary Information

supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

He, S., He, Y. & Jin, Y. Revealing the truth about ‘trapped rainbow’ storage of light in metamaterials. Sci Rep 2, 583 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00583

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00583

This article is cited by

-

Suppressed phase separation of mixed-halide perovskites confined in endotaxial matrices

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Toppling dynamics of a mass-varying domino system

Nonlinear Dynamics (2019)

-

Completely stopping microwaves with extremely enhanced magnetic fields

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Slow light in a hyperbolic metamaterial waveguide cladded with arbitrary nonlinear dielectric materials

Applied Physics B (2018)

-

Half-spaced substrate integrated spoof surface plasmon polaritons based transmission line

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.