Abstract

Two paradigm shifts in DNA sequencing technologies—from bulk to single molecules and from optical to electrical detection—are expected to realize label-free, low-cost DNA sequencing that does not require PCR amplification. It will lead to development of high-throughput third-generation sequencing technologies for personalized medicine. Although nanopore devices have been proposed as third-generation DNA-sequencing devices, a significant milestone in these technologies has been attained by demonstrating a novel technique for resequencing DNA using electrical signals. Here we report single-molecule electrical resequencing of DNA and RNA using a hybrid method of identifying single-base molecules via tunneling currents and random sequencing. Our method reads sequences of nine types of DNA oligomers. The complete sequence of 5′-UGAGGUA-3′ from the let-7 microRNA family was also identified by creating a composite of overlapping fragment sequences, which was randomly determined using tunneling current conducted by single-base molecules as they passed between a pair of nanoelectrodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Human Genome Project has provided a complete genetic road map, which has expanded our knowledge about not only biology of humans but also of other organisms. We believe that the emerging high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies would allow us to acquire such information at a much greater rate than those possible using the current technologies. For example, we will be able to follow up on the evolution of viral and bacterial drug resistance in real time, uncover the huge diversity of novel genes that are currently inaccessible and provide physicians with genomics-based preventive diagnostics and therapeutics that specifically and comprehensively target individual patients1,2,3.

First and second generation DNA sequencing technologies identify nucleotides through light emission. They require PCR for the amplification of sequencing templates in order to produce sufficient material to generate detectable signals. Third generation DNA sequencing technologies detect single nucleotides directly by changes in electric current, thereby negating the need for either fluorescent probes or PCR amplifications1,2,3,4.

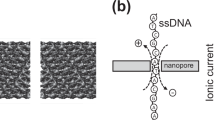

Nanopores are a key component of third generation DNA sequencing technologies5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. These devices provide two possible approaches to DNA sequencing. The first includes use of bio-nanopores5,6,7,8 or solid-state nanopores9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. As each nucleotide in a DNA strand translocates through a nanopore, it specifically modulates the ionic current being passed through the nanodevice; this allows the identification of each nucleotide and eventually of the DNA sequence6,7. The second method includes use of gating nanopores18,19,20,21,22,23, in which DNA can be identified via the tunnelling current they conduct as they pass between a pair of nanoelectrodes24,25,26 (Fig. 1a). Measurable changes in the current occur in response to small differences in the electronic structure of the DNA molecule, making it possible to identify the type and arrangement of individual base molecules.

Schematic diagram of single-molecule electrical sequencing of DNA and RNA.

(a) Single base molecules on a DNA molecule in a solution are identified via a tunnelling current that passes between nanoelectrodes. Nanogaps of 0.8 nm were fabricated using a nano-MCBJ. A constant DC voltage of 0.4 V was applied between the nanoelectrodes and electrical signals were measured at a sampling rate of 10 KHz. (b) Molecular structures of deoxynucleoside monophosphates of DNA and (c) nucleoside monophosphates of RNA.

Single-molecule electrical sequencing via tunnelling current provides two means of sequencing long, single-stranded DNA molecules. One method enables one-by-one identification of the base molecules along a long, single-stranded DNA molecule22. The alternative method enables the determination of the sequence of a DNA molecule as a composite of overlapping randomly-fragmented sequences; this method is aptly termed as random DNA sequencing27,28.

Because single-molecule electrical-random sequencing has not yet been reported, the determination of random sequences of short DNA and RNA composed of known sequences (resequencing DNA and RNA) is a significant milestone in sequencing. Here we report about single-molecule electrical resequencing of DNA and RNA by a hybrid method of identifying single base molecules via a tunnelling current and random sequencing. Nine DNA oligomers composed of 3 base molecules were sequenced by our single-molecule electrical sequencing method. 5′-UGAGGUA-3′ miRNA was completely resequenced by our hybrid method of single-molecule electrical sequencing and random resequencing.

Results

Single-molecule identification of DNA and RNA bases

In this study, we investigated the conductance values of the four bases of DNA and RNA. Four deoxyribonucleoside monophosphates (dAMP, dCMP, dGMP, dTMP) and four ribonucleoside monophosphates (rAMP, rCMP, rGMP, rUMP) could be identified by the tunnelling current they conducted as they passed between a pair of nanoelectrodes separated by a gap of 0.8 nm (Fig. 1). This gap was set using a nanofabricated, mechanically controllable break junction (nano-MCBJ)29 (Supplementary Figs. S1–S6). We also determined the time dependence of the electrical current between the nanoelectrodes when each of the single nucleotides stochastically passed through the nanoelectrode gap by Brownian motion. Spike-like electrical signals were observed at high frequencies for approximately 100 ms and peak electrical currents ranged from 10 pA to several hundred pA, indicating the presence of a base molecule between the nanoelectrodes (Figs. 2a and 2b and Supplementary Fig. S7). The electrical signals were characterised by Ip and td, which were defined as the maximum current and the duration of the current, respectively. Typical values of Ip and td for dGMP were 100 pA and 1 ms, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Single-molecule identification of deoxynucleoside monophosphates of DNA and nucleoside monophosphates of RNA.

(a) Typical current–time profiles obtained from 0.10 μM solutions of dGMP. (b) Expanded figure of a typical electrical signal, which is characterized by td and Ip, where Ip is defined as the maximum current and td as the duration of the current. (c) Conductance histograms of four deoxynucleoside monophosphates of DNA, constructed from 1000 Ip for each molecule. The blue, red, purple and green lines indicate the single-molecule conductance of dGMP, dAMP, dCMP and dTMP, respectively. The colour codes of lines corresponding to the Ip histograms represent Gaussian fitted lines. (d) Conductance histograms of four nucleoside monophosphates of RNA. The blue, red, purple and green lines indicate the single-molecule conductance values of rGMP, rAMP, rCMP and rUMP, respectively. The colour codes of lines corresponding to the Ip histograms represent Gaussian fitted lines. The single-molecule conductance values are summarized in Table 1. The Ip histograms were constructed from 1000 Ip data points for each nucleoside monophosphate. (e) Typical td histograms of dGMP and GGG constructed from 1000 td data. The line curve shows a Gaussian fitted line with a peak td of approximately 1 ms.

Single-molecule conductance (Ip/V) histograms were then constructed from the Ip data using approximately 1000 spikes for each molecule and were analysed using Gaussian fit curves. The G values (the peak value in each conductance histogram) for each single nucleotide was found to be in the following order: dGMP (87 pS) > dAMP (67 pS) > dCMP (60 pS) > dTMP (39 pS) for DNA and rGMP (123 pS) > rAMP (92 pS) > rCMP (64 pS) > rUMP (50 pS) for RNA. The relative G normalized by dGMP and rGMP was also compared to explore the order of conductance and the following results were found: dGMP = rGMP = 1, dAMP (0.77) ∼ rAMP (0.75) > dCMP (0.69) > rCMP (0.52) > dTMP (0.45) > rUMP (0.41) (Table 1). Calculations based on density functional theory indicated that the order based on the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy was as follows: guanine (−5.7 eV) > adenine (−5.9 eV) > cytosine (−6.1 eV) > thymine (−6.6 eV) > uracil (−6.9 eV) (Supplementary Table S1). Note that this order corresponds to the order of the relative G values, suggesting that our single-molecule electrical detection method can identify molecular species based on characteristic energy levels, particularly the HOMO energy level.

Single-molecule electrical resequencing of DNA oligomers

In addition, dual level conductance–time profiles were obtained for TGT, GTG, ATA, CAC and GAG DNA oligomers (Figs. 3b–3f and Supplementary Fig. S9). Single-molecule conductance histograms constructed from the G-t profiles showed two peaks corresponding to dual level conductance. When the relative G for the higher G corresponding to single-molecule conductance of dGMP was set to 1, the relative G for the lower G in TGT, GTG and GAG conductance histograms was calculated as 0.29 ± 0.12, 0.35 ± 0.12 and 0.68 ± 0.08, respectively. (Table 2). Since these values were within the ranges of the relative G for dTMP (0.45 ± 0.12) and dAMP (0.77 ± 0.20), the obtained values, 0.29, 0.35 and 0.68, were assigned to dTMP, dTMP and dAMP, respectively. Similarly, when the higher G was set relative to G = 0.77 (obtained from the conductance histogram for dAMP), the lower relative G in ATA and CAC conductance histograms was calculated to be 0.41 ± 0.07 and 0.52 ± 0.11, respectively. Since these values were within the ranges of the relative G for dTMP (0.45 ± 0.12) and dCMP (0.69 ± 0.25), the obtained values, 0.41 and 0.52, were determined to be those of dTMP and dCMP, respectively. Therefore, the type of base molecules forming DNA oligomers could be identified using the relative G of the single base molecules.

Resequencing of DNA oligomers.

Relative conductance (G)–time profiles of (a) GGG, (b) TGT, (c) GTG, (d) ATA, (e) CAC and (f) GAG. The relative G values are summarized in Table 2. The left panels in each figure show the related G histograms. Upper and lower panels show expanded I-t and smoothed G-t profiles of (g) TGT and (h) GTG. The blue, red, purple and green lines and bands in all figures represent the relative G and its dGMP, dAMP, dCMP and dTMP bands, respectively.

To resequence the base molecules of a single DNA or RNA molecule, we had to extract information about the arrangement of the bases from the I-t profiles. Since the electric signals were composed of Ip and td and the type of base molecule was determined from Ip, the base arrangement could be identified using td. Here we investigated the I-t profiles of dGMP and the GGG DNA oligomer (Supplementary Fig. S10. Supplementary Figure S11 shows I-t profiles of AAA, CCC and TTT). One-level spike-like signals were observed in the I-t profiles of GGG as well as dGMP (Fig. 3a). The td histogram of dGMP showed a peak at approximately 0.8 ms, while that of GGG gave a peak at approximately 0.8 ms and extended to 1000 ms (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. S8). Therefore, it was clear that extraction of electrical signals with a td of more than 2 ms (∼0.8 ms x 3) was required. Using this criterion, electrical signals of single DNA molecules consisting of n base molecules should show n plateaus. For example, the electrical signals of G and T, GT and TG, TGT and GTG would be expected to show one, two and three plateaus, respectively. Thus, the criteria for identifying electrical signals from single DNA molecules consisting of three base molecules are that td should be >2 ms and that the number of plateaus should be 3.

Electrical signals (Figs. 3b–3f) were then automatically extracted using the criteria described above and three obvious plateaus were observed (Supplementary Figs. S12 and S13, Tables S2 and S3). In one case, two lower plateaus of T were observed in the first and third positions, with G forming the middle higher plateau (TGT) (Fig. 3g); in the other case, G was observed to form the first and third higher plateaus, with T in the lower centre position (GTG) (Fig. 3h). The results clearly demonstrated that DNA oligomers could be resequenced. In the experimental conditions using the nano-MCBJ not only GTG and TGT but also G, T, TG, GT, GTGTT and TGTGT could be identified because single DNA molecules were stochastically trapped between the nanoelectrodes because of Brownian motion. For example, when Brownian motion turns over a single TGT oligomer at the T position between nanoelectrodes, we can obtain unexpected G-t profiles such as TGTGT composed of a forward sequence (TGT) and a backward sequence (GT). Therefore, single-molecule electrical resequencing using nano-MCBJ can be used to randomly identify sequences of single base DNA molecules.

Single-molecule electrical random resequencing of miRNA

In random sequencing methods27,28, a DNA molecule is broken up randomly into numerous small fragments. Multiple overlapping reads for the target DNA are obtained by performing several rounds of fragmentation and sequencing. Computer programs then use the overlapping ends of different randomly fragmented sequences to assemble them into continuous sequences (sequence contigs) and further to assemble the contigs into a continuous sequence. To assist in the effort to evaluate the potential for single-molecule electrical resequencing, we selected a common sequence (5′-UGAGGUA-3′) from the let-7 miRNA family30, which is a well-known cancer marker and consists mainly of 22 bases.

First, when we measured the I-t profiles of miRNA, the current histogram constructed from the profile showed three peaks at I = 70 pA, 50 pA and 33 pA (Fig. 4a). The peaks were assigned to rGMP, rAMP and rUMP, since the relative G values of 1, 0.71 and 0.47 agree with those of these single base molecules for RNA (Table 3). This result shows that three base molecules exist in the miRNA. Fragment sequences were determined using the same procedure as was used to resequence DNA oligomers. In particular, electric signals fluctuating with a period of less than 0.8 ms were ignored because the characteristic dwell time for single bases was 0.8 ms, as shown in Fig. 2e. Figures 4b–4d show typical analysed electrical signals. As is clearly shown in the figures, A, G, U, AU, UGAGG and UGAGGUA were identified as fragment sequences (Supplementary Fig. S14). When 133 electrical signals were analysed in the same way, we obtained randomly fragmented sequences, including 19×A, 15×G, 44×U, 5×UA, 10×GA, 5×UG and the 35 fragments shown in Fig. 4e. As mentioned when resequencing DNA oligomers, characteristic fragment sequences (e.g. GAGAGGUA, UGAGGAGA and UGAGGUAUA) were obtained because of stochastic motions originating from Brownian motion. In addition, both the forward and reverse reads were observed. For example, out of the 15 asymmetric reads of more than three bases (e.g. UGA and GAGGUA), the forward (UGA and GAGGUA) and reverse (AGU and GAGGUA) had yields of 60% and 40%, respectively. Furthermore, we acquired misread fragments of AGAUA and GAGGUG corresponding to AGGUA and GAGGUA, respectively, because the relative G band of rGMP overlaps that of rAMP.

Random resequencing of 5′-UGAGGUA-3′ microRNA.

(a)Typical I–t profiles from a 1.0 μM solution of UGAGGUA with 100 mM phosphate buffer. (b)–(d) Typical relative G histograms, raw and smoothed G-t profiles of randomly fragmented sequences. Purple, red and blue lines and bands show relative G values (Table 3) and rUMP, rAMP and rGMP bands, respectively. (U, G, A, UA), (AU, UGAGG) and (U, UA, UGAGGUA) were resequenced according to the G-t profiles in (b), (c) and (d), respectively. (e) The 35 randomly fragmented sequences used for resequencing the microRNA. Sequence contigs 1–4 were assembled by fragment sequences within the red, green, blue and purple frames. The full sequence of the microRNA was determined by overlapping the 4 sequence contigs.

Next, we used the overlapping ends of the different randomly fragmented sequences to assemble these into continuous sequences (sequence contigs) and then to assemble the contigs into a continuous sequence. One and two read signals (short signals) were too short to determine their assigned positions on the sequence of miRNA. On the other hand, the longer signals (over three reads) can be assigned on the sequence of the miRNA, as opposed to the known sequence of the miRNA. Therefore, only the longer signals were used for signal assembly and formation of contigs. The 35 fragment sequences were used to assemble the sequence contigs (Fig. 4e). Sequence contig 1 was assembled as UGA using 13 fragment sequences within the red frame in Fig. 4e. Similarly, sequence contigs 2–4 were assembled as GAGG, AGGUA and AGGU, respectively, using 17, 10 and 13 fragment sequences within the green, blue and purple frames in the same figure. Since there was no sequence gaps between the sequence contigs due to the short miRNA used, the four sequence contigs were assembled as UGAGGUA. The read error was 10% because by using 35 fragments, the number of wrong read bases (gray bases shown in Fig. 4e) was 17 out of a total of 168 read bases.

Discussion

Single base molecule can be identified using G in DNA and RNA monomers, though conductance histograms exhibit significant overlap due to the large full width at half maximum (FWHM) of G (Figs. 2c and 2d). The large FWHM largely originates from the fact that tunneling current is highly sensitive to configurations of single base molecules with respect to the nanoelectrodes. Therefore, in an effort to decrease the FWHM and to improve the sequencing reliability, it is important to decrease the degree of freedom of configurations.

The electrical measurement of DNA monomers, DNA oligomers and a miRNA showed interesting results to provide one method to reduce the FWHM. We found large FWHM of DNA and RNA monomers, where the FWHM of dGMP, dAMP and dCMP was more than 0.40 while that of rGMP and rAMP were 0.88 and 0.54, respectively (Table 1). However, the FWHM of dGMP in TGT and GAG oligomers decreased though that in GTG showed a slight increase (Table 2). The FWHM of dAMP, dCMP, dTMP in 4 DNA oligomers reduced and that of dCMP in CAC oligomer reduced to 48% of that of single dCMP molecule. Furthermore, fragmented sequences of miRNA had smaller FWHM (Table 3). In particular, the largest FWHM (0.88) of rGMP in the miRNA among 8 base molecules reduced to 36%. The FWHM of rAMP in the miRNA also reduced to 59% of that in the single base molecule. As a result, conductance histograms of rGMP, rAMP and rUMP in fragmented sequences exhibited no overlap within the FWHMs (Figs. 4b–4d).

Reduction of FWHM of base molecules in DNA oligomers and a miRNA comes from decreasing the degree of freedom of configurations, where chemical bonds via sugars and phosphates restrict conformations of single base molecules. In this study, single molecules could move around nanoelectrodes fabricated by nano-MCBJ. Therefore, using gating nanopores composed of nanoelectrodes and nanopores, we would be able to obtain smaller FWHM because configurations of single DNA and RNA molecules are strongly restricted by nanopores.

Methods

Fabrication of nanogaps

A microfabricated MCBJ was employed to form nucleotide-sized electrode gaps (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). The fabrication procedures for MCBJs are described elsewhere.29 First, we coated a phosphor bronze substrate with a thin polyimide layer for electrical insulation. A gold nanojunction was then fabricated using electron beam lithography and a subsequent lift-off process. The junction was then exposed to isotropic reactive ion etching using CF4/O2 gas to remove the underlying polyimide and obtain a free-standing gold nanobridge. The MCBJ sample was mounted in a three-point bend configuration. The substrate was then bent and the junction broken mechanically to form a pair of gold nanoelectrodes. The junction conductance was monitored using a Keithley 6487 picoammeter (Keithley) under a DC bias voltage of 0.1 V. A 10-kΩ resistor was connected in series during this process to protect the junction from overcurrent-induced electromigration failure. Special care was taken while adjusting the electrode gap size by a self-breaking technique.

Materials

We purchased dAMP (2′-deoxyadenosine-5′-monophosphate: Sigma-Aldrich), dCMP (2′-deoxycytidine-5′-monophosphate sodium salt: Sigma-Aldrich), dGMP (2′-deoxyguanosine-5′-monophosphate sodium salt hydrate: Sigma-Aldrich), dTMP (Thymidylic acid disodium salt: Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. (TCI)), rAMP (2′-adenosine-5′-monophosphate disodium salt: Oriental yeast), rCMP (cytidine 5′-monophosphate disodium salt: TCI), rGMP (Guanosine 5′-monophosphate sodium salt hydrate: TCI) and rUMP (uridine 5′-monophosphate disodium salt hydrate: TCI). These were used to make 10 μM aqueous solutions without further purification. DNA oligomers were synthesized by FASMAC Co., Ltd. and Hokkaido System Science Co., Ltd. RNA oligomers were synthesized by Operon Biotechnologies Co., Ltd. No buffer was added to the sample solutions of single nucleotides. A total of 100 mM phosphate buffer was used for all the sample DNA and RNA oligomer aqueous solutions.

Test procedure

We formed a 0.8-nm electrode gap in a dilute Milli-Q solution of a target nucleotide molecule at a concentration of 0.10 μM. The current across the electrodes was recorded at 10 kHz using a custom-built logarithmic current amplifier and a PXI-4071 digital multimeter (National Instruments) under a DC bias voltage of 0.4 V. After every 1 h of I-t measurement, we replaced the MCBJ sample with a new one. With the single-nucleotide measurements, in order to suppress a possible contamination effect on the measurements, about 20 samples were used for each nucleotide to obtain approximately 1000 spike-like signals for constructing the Ip histograms. For the oligonucleotide measurements, about 10 samples were used for each sample oligonucleotide to obtain approximately 200 signals.

Resequencing procedure

Resequencing was performed using the following procedure: (1) measurement of I–t profiles; (2) extraction of electrical signals with td > 2 ms; (3) plotting of I histogram using all data of I–t profiles; (4) determination of current baseline on the basis of the lowest conductance peak; (5) smoothing of all data in an attempt to obtain plateaus; (6) determination of base-type molecules using the relative single-molecule conductance of base molecules, as shown in Table 1; (7) base assignment based on relative single-molecule conductance and plateaus. The detailed sequencing procedures for GGG and GTG are shown in Supplementary Figs. S12 and S13, respectively.

References

Branton, D. et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotech. 26, 1146–1153 (2008).

Schloss, J. A. How to get genomes at one ten-thousandth the cost. Nat. Biotech. 26, 1113–1115 (2008).

Service, R. F. The race for the $1000 genome. Science 311, 1544–1546 (2006).

Zwolak, M. & Di Ventra, M. Colloquim: Physical approaches to DNA sequencing and detection. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 141–165 (2008).

Deamer, D. W. & Branton, D. Characterization of nucleic acids by nanopore analysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 817–825 (2002).

Clarke, J. et al. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 265–270 (2009).

Stoddart, D., Heron, A. J., Mikhailova, E., Maglia, G. & Bayley, H. Single-nucleotide discrimination in immobilized DNA oligonucleotides with a biological nanopore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7702–7707 (2009).

Olasagasti, F. et al. Replication of individual DNA molecules under electronic control using a protein nanopore. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 798–806 (2010).

Storm, A. J., Chen, J. H., Ling, X. S., Zanbergen, H. W. & Dekker, C. Fabrication of solid-state nanopores with single-nanometre precision. Nat. Mater. 2, 537–541 (2003).

Fologea, D. et al. Detecting single stranded DNA with a solid state nanopore. Nano Lett. 5, 1905–1909 (2005).

Storm, A. J. et al. Fast DNA translocation through a solid-state nanopore. Nano Lett. 5, 1193–1197 (2005).

Keyser, U. F. et al. Direct force measurements on DNA in a solid-state nanopore. Nat. Phys. 2, 473–477 (2006).

Dekker, C. Solid-state nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 209–215 (2007).

Gershow, M. & Golovchenko, J. A. Recapturing and trapping single molecules with a solid-state nanopore. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 775–779 (2007).

Singer, A. et al. Nanopore based sequence specific detection of duplex DNA for genomic profiling. Nano Lett. 10, 738–742 (2010).

Hall, A. R. et al. Hybrid pore formation by directed insertion of α-haemolysin into solid-state nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 874–877 (2010).

Garaj, S. et al. Graphene as a subnanometre trans-electrode membrane. Nature. 467, 190–193 (2010).

He, J., Lin, L., Zhang, P. & Lindsay, S. Identification of DNA basepairing via tunnel-current decay. Nano Lett. 7, 3854–3858 (2007).

Chang, S. et al. Tunneling readout of hydrogen-bonding-based recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 297–301 (2009).

Taniguchi, M., Tsutsui, M., Yokota, K. & Kawai, T. Fabrication of the gating nanopore device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 123701–123703 (2009).

Tsutsui, M., Taniguchi, M., Yokota, K. & Kawai, T. Identifying single nucleotides by tunnelling current. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 286–290 (2010).

Huang, S. et al. Identifying single bases in a DNA oligomer with electron tunnelling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 868–873 (2010).

Ivanov, A. P. et al. DNA Tunneling detector embedded in a nanopore. Nano Lett. 11, 279–285 (2011)

Zwolak, M. & and Di Ventra, M. Electronic signature of DNA nucleotides via transverse transport. Nano Lett. 5, 421–424 (2005).

Lagerqvist, J., Zwolak, M. & Di Ventra, M. Fast DNA sequencing via transverse electronic transport. Nano Lett. 6, 779–782 (2006).

Lagerqvist, J., Zwolak, M. & Di Ventra, M. Influence of the environment and probes on rapid DNA sequencing via transverse electronic transport. Biophys. J. 93, 2384–2390 (2007).

Edwards, A. & Caskey, C. T. Closure Strategies for Random DNA Sequencing. Methods. 3, 41–47 (1991).

Fleischmann, R. et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269, 496–512 (1995).

Tsutsui, M., Shoji, K., Taniguchi, M. & Kawai, T. Formation and self-breaking mechanism of stable atom-sizedjunctions. Nano Lett. 8, 345–349 (2007).

Roush, S. & Slack, F. J. The let-7 family of micro RNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 505–516 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This research is partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through its Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. O., M. Taniguchi and T. K. planned and designed experiments. T. O., K. M., M. Tsutsui, M. F. and M. Taniguchi fabricated MCBJ devices, exhibited electrical measurements and performed data analyses. T. O., M. Taniguchi and T. K. co-wrote paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ohshiro, T., Matsubara, K., Tsutsui, M. et al. Single-Molecule Electrical Random Resequencing of DNA and RNA. Sci Rep 2, 501 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00501

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00501

This article is cited by

-

Direct biomolecule discrimination in mixed samples using nanogap-based single-molecule electrical measurement

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Single-molecule RNA sequencing for simultaneous detection of m6A and 5mC

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Top-down nanofabrication approaches toward single-digit-nanometer scale structures

Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology (2021)

-

Time-resolved neurotransmitter detection in mouse brain tissue using an artificial intelligence-nanogap

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Solid-state nanopores towards single-molecule DNA sequencing

Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.