Abstract

Aminoglycoside antibiotics rapidly enter and kill cochlear hair cells via apical mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) channels in vitro. In vivo, it remains unknown whether systemically-administered aminoglycosides cross the blood-labyrinth barrier into endolymph and enter hair cells. Here we show, for the first time, that systemic aminoglycosides are trafficked across the blood-endolymph barrier and preferentially enter hair cells across their apical membranes. This trafficking route is predominant compared to uptake via hair cell basolateral membranes during perilymph infusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, like gentamicin, are widely-used and clinically essential for preventing or treating Gram-negative bacterial sepsis and tuberculosis1. However, these drugs carry significant risk of nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. In the inner ear, systemic aminoglycosides cross the blood-labyrinth barrier (BLB) and preferentially kill cochlear sensory hair cells, leading to lifelong hearing loss and deafness1, the most prevalent sensory disability worldwide. The cochlear trafficking route(s) by which systemic aminoglycosides reach hair cells has remained an important, yet unanswered, question for over 60 years.

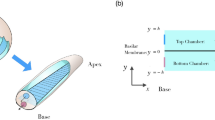

Cochlear hair cells are highly specialized neuro-epithelial cells immersed in two electrochemically distinct extracellular fluids. Their basolateral membranes are immersed in perilymph that fills the scala tympani and extracellular spaces of the organ of Corti (Fig. 1). Their apical membranes, including the mechanically-sensitive stereocilia, are bathed in endolymph. Tight junctions couple all cells lining the endolymphatic space, limiting paracellular ion movements between endolymph and perilymph (Fig. 1). Endolymph is rich in potassium and low in sodium and calcium (157, 1.3, 0.023 mM respectively); perilymph has typical extracellular levels of potassium, sodium and calcium (4.2, 148, 1.3 mM respectively)2. The distinctive ionic composition of endolymph is regulated by the stria vascularis that actively transports potassium into endolymph; while the positive endolymphatic potential (+80 mV) drives sodium out through non-specific cation channels in sensory and non-sensory cells. The positive endolymphatic potential also provides a rapid potassium-rich depolarizing current into hair cells via mechanically-gated mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) channels located at the tips of most hair cell stereocilia3. These MET channels are non-selective cation channels permeable to aminoglycosides in vitro4,5, raising the question of whether systemic aminoglycosides are trafficked into endolymph prior to entering hair cells via MET channels in vivo. The most direct route for vascular aminoglycosides to enter endolymph is to cross the tight junction-coupled endothelial cells of strial capillaries into the intra-strial space and be taken up by marginal cells, prior to clearance into endolymph (Fig. 1). Previous in vivo studies6,7 revealed that systemic fluorescently-tagged gentamicin (GTTR) was preferentially taken up by the stria vascularis in the cochlea, providing suggestive, but inconclusive, evidence for trans-strial trafficking of systemic gentamicin into endolymph and hair cells.

Diagram illustrating potential intra-cochlear trafficking of systemic aminoglycosides to hair cells.

Endolymph trafficking route is indicated by red dashed arrow, while perilymph trafficking route is indicated by blue dashed arrows. The endolymphatic space is encapsulated by tight junctions depicted by thick black lines. Cochlear capillaries are located in the stria vascularis (a), in the modiolus (b), on the scala tympani side of the basilar membrane (c) and within the spiral ligament of the lateral wall (d).

Alternatively, vascular aminoglycosides could traffic through the tight junction-coupled endothelial cells of non-strial capillaries, in the spiral limbus, basilar membrane and spiral ligament and load perilymph in the scala tympani8, with access to hair cell basolateral membranes (Fig. 1). However, there is little evidence that aminoglycosides cross hair cell basolateral membranes.

This study provides evidence that systemic gentamicin is trafficked across the blood-endolymph barrier and preferentially enter hair cells from endolymph in vivo. This has scientific and clinical implications for understanding the trafficking mechanisms involved and developing novel, systemic approaches to preventing gentamicin-induced ototoxicity in humans.

Results

To determine which intra-cochlear trafficking route aminoglycosides primarily follow to enter hair cells, we used both fluorescently-tagged gentamicin-Texas Red (GTTR) or immunodetection of gentamicin (Fig. 2c). Although larger in size and mass than gentamicin, GTTR is cationic, permeates the MET channel and is rapidly localized at hair cell stereocilia following systemic injection, like gentamicin5,7.

Greater hair cell uptake of GTTR via endolymph trafficking.

(a) Diagram illustrating systemic GTTR delivery with scala tympani perilymph wash. AP, artificial perilymph. (b) Diagram illustrating perilymph infusion with GTTR. (c) Space-fill models of gentamicin and GTTR. Robust GTTR fluorescence in the stria vascularis (d) and in OHCs, IHCs and pillar cells of the organ of Corti (e) after systemic GTTR delivery with perilymph wash. Negligible GTTR fluorescence in the stria vascularis (f) and weak fluorescence in the organ of Corti (g) after scala tympani infusion of GTTR. Negligible autofluorescence (λ >615 nm) in the stria vascularis (h) and organ of Corti (i). Scale bars = 20 μm. All images were acquired and processed using identical settings. (j) CAPs were largely maintained in the 2–9 kHz region (gray region) corresponding to the third coil from the cochlear apex10. (k) Cochlear sensitivity was preserved during scala tympani infusion of GTTR. (l) The intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs was quantified from single confocal planes. More robust fluorescence was present in cochleae exposed to systemic GTTR plus perilymph wash compared to scala tympani infusion of GTTR (p < 0.001; n = 8 per condition, post hoc unpaired t-test). Red (or magenta) circles indicate the same batch of GTTR used among experiments. After scala tympani infusion of GTTR, fluorescence in OHCs was weak, but detectable and statistically greater than in untreated OHCs (p = 0.0009; n = 8 per condition, unpaired t-test). A.U., arbitrary units.

GTTR was given intravenously (1 mg/kg gentamicin base) while the scala tympani was perfused with artificial perilymph to reduce GTTR access to the basolateral membranes of hair cells (Fig. 2a). After 30 minutes, cochlear tissues were systemically perfusion-fixed and processed for confocal microscopy. Robust GTTR fluorescence was observed in single optical sections of the stria vascularis and organ of Corti (Fig. 2d and e respectively), similar to cochleae treated with systemic GTTR without perilymph wash (Supplementary Fig. 1). Serum levels of GTTR were ∼7.0 μg/ml (n = 5) 15 minutes post-injection.

The reciprocal drug delivery paradigm was to infuse 1.4 μg/ml GTTR in artificial perilymph through the scala tympani for 30 minutes, providing GTTR access only to the basolateral membranes of hair cells (Fig. 2b). This dose was derived from the perilymph-to-serum aminoglycoside ratio of 20% after a 6-hour i.v. infusion9 and likely higher than GTTR levels in perilymph 30 minutes after systemic injection7. After 30 minutes, there was negligible GTTR fluorescence in the stria vascularis and weak fluorescence in hair cells (Fig. 2f and g respectively). Two batches of GTTR were used and cellular fluorescence intensities were found to be segregated by batch (Fig. 2l). A two-way ANOVA revealed fluorescence variation in the batches of GTTR used (F[1,12] = 54.44, p < 0.0001) and more importantly, fluorescence variation in the GTTR delivery route used (F[1,12] = 245.35, p < 0.0001). Post hoc unpaired t-tests (assuming unequal variances) confirmed that the intensity of systemic GTTR in hair cells after trafficking across the strial blood-endolymph barrier was significantly greater than that delivered by scala tympani infusion (p < 0.001, n = 8; Fig. 2l), indicating that hair cells preferentially take up GTTR from endolymph.

The weak fluorescence in OHCs following scala tympani infusion with GTTR (Fig. 2g) was significantly greater than autofluorescence in OHCs without GTTR exposure (Fig. 2i, 2l; p = 0.0009, n = 8, unpaired t-test). In contrast, strial tissues had negligible fluorescence following scala tympani infusion of GTTR that was not statistically different from the extremely weak autofluorescence observed in untreated stria vasculari imaged at the same laser excitation intensities as in cochleae treated with systemic GTTR (p = 0.22, n = 6, unpaired t-test; Fig. 2f and h), indicating negligible trafficking of GTTR from perilymph into endolymph via the stria vascularis. Cochleae treated systemically with hydrolyzed Texas Red also had negligible fluorescence in hair cells (Supplementary Fig. 1e and f). Thus, weak fluorescence in hair cells following scala tympani infusion of GTTR indicates that hair cells could take up GTTR across their basolateral membranes. However, this perilymph trafficking route is inefficient compared to the robust GTTR fluorescence observed in the stria vascularis and hair cells following systemic injection of GTTR implicating trans-strial trafficking into endolymph and hair cells.

Imaging data were collected and analyzed from only sensitive cochleae with near-normal compound action potentials (CAPs). Sealing the perfusion catheter occasionally induced mild CAP threshold shifts in the 12 to 24 kHz region at the base of the cochlea (e.g. Fig. 2j). However, cochlear sensitivity was well-maintained in the 2–9 kHz frequency range corresponding to the third cochlear coil (from the apex) in either experimental paradigm (Fig. 2j and k) derived from the murine frequency-place map10. This indicates that relatively normal cochlear physiological function was maintained during perfusion (see Discussion).

Since GTTR has a larger molecular mass than gentamicin, we repeated the same experimental paradigms using gentamicin and processed the tissues for immunofluorescence. The results were qualitatively similar to that with GTTR, with characteristic gentamicin immunolabeling in hair cells following systemic gentamicin delivery and perilymph wash (Fig. 3a and b). Following infusion of gentamicin through the scala tympani, the immunofluorescence signal was weak and largely non-specifically distributed throughout the organ of Corti (i.e., not localized to specific cell types; Fig. 3c and d). Significantly, CAP thresholds and thus cochlear sensitivity, were maintained in the cochlear segment of interest (Fig. 3e and f).

Gentamicin immunofluorescence also supports a primary endolymph trafficking route for aminoglycosides.

(a) Characteristic gentamicin immunofluorescence in hair cells in the organ of Corti after systemic gentamicin plus perilymph wash. Inner hair cell bodies are not in the same focal plane (b). (c) Gentamicin immunofluorescence had little cell specificity in the organ of Corti after perilymph infusion. Inner hair cell bodies are not in the same focal plane (d). Scale bar = 20 μm. All confocal images acquired and processed using identical settings. (e) Cochlear sensitivity was largely maintained in a cochlea receiving systemic gentamicin plus perilymph wash. Gray area indicates the frequency region corresponding to the third coil of the guinea pig cochlea. (f) Cochlear sensitivity was also preserved in a cochlea receiving scala tympani infusion of gentamicin.

Discussion

Previous studies reported only very low levels of aminoglycosides in endolymph compared to perilymph in vivo8,9. The +80-mV endolymphatic potential will electrophoretically drive the cationic aminoglycosides present in endolymph through hair cell MET channels, or other aminoglycoside-permeant cation channels into supporting cells4,5,7. This will selectively increase the risk of hair cell toxicity5,11 and simultaneously reduce aminoglycoside levels in endolymph compared to perilymph.

The sensitive hearing monitored by CAP recording during these experiments indicates that the strial BLB maintained its integrity. Loss of BLB integrity, or paracellular extravasation of drug-laden serum into the intra-strial space, would short-circuit the electrophysiological environment in the cochlea with consequent loss of both endolymphatic potential and cochlear sensitivity12,13. This was not observed in these experiments. Furthermore, non-selective, aminoglycoside-permeant cation channels cannot be present in the basolateral membrane of marginal cells14,15, suggesting that uptake of aminoglycosides from the intra-strial space into marginal cells requires active or electrogenic transport across their basolateral membranes. Identifying this molecular mechanism will initiate new, systemic strategies to pharmacologically block aminoglycoside trafficking across the blood-endolymph barrier and into hair cells and subsequent cochleotoxicity.

In this study, we used fluorescently-tagged and native gentamicin. Gentamicin induces both cochleotoxicity and vestibulotoxicity and intratympanic administration of gentamicin is used to manage Meniere's disease and vertigo16. Our data show that, in relatively normal physiological conditions, hair cells take up little gentamicin from perilymph compared to trans-strial trafficking of systemic gentamicin from strial capillaries into endolymph and hair cells. However, perilymph is a reservoir for gentamicin deposition8 and pathophysiological conditions, such as Meniere's Disease, could potentially enhance cochlear hair cell uptake of gentamicin from perilymph17. Similarly, trafficking of systemic aminoglycosides to hair cells can also be modulated by acoustic trauma, bacterial sepsis or exposure to loop diuretics18,19,20,21. Although loop diuretics block the sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporter prevalent on the basolateral membrane or marginal cells, the integrity of the blood-labyrinth and perilymph-endolymph barriers are maintained22. This further implicates a transcellular trafficking pathway for gentamicin across the strial blood-endolymph barriers.

In summary, gentamicin is trafficked across the strial BLB into endolymph preferentially enter hair cells across their apical membranes, compared to perilymph trafficking, answering a long-standing question in ototoxicity.

Methods

Animal preparation

Albino guinea pigs (270–500 g, Dunkin-Hartley from Charles River Laboratories International, Inc.) of either sex with Preyer's reflex were anesthetized (ketamine 30 mg/kg and xylazine 5 mg/kg, i.m.). Supplemental doses were given on recovery of toe-pinch withdrawal reflex. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a servo-regulated heating blanket. Experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health & Science University (IS00000351).

The animal was supine to expose the ventral aspect for surgical procedures. The head was held firmly in place and a tracheotomy performed to insert a ventilation tube for unobstructed breathing. A ventral-postauricular approach exposed the left auditory bulla, with the medial portion of the external auditory canal preserved to allow placement of a sound delivery tube. The temporal bulla was opened to access the cochlea.

Measurement of CAPs

A ball electrode made of Teflon-coated silver wire was placed in the round window niche and fixed on the bulla with carboxylate cement. Tone bursts (10 ms duration, 1-ms rise/fall) generated using a 16-bit D/A converter (Tucker Davis Technologies) were delivered to the ear canal to evoke CAPs. The round window signal was amplified 1,000x by an AC amplifier (CWE Inc, model BMA-200) and a custom-designed AC amplifier. After A/D conversion and averaging, the evoked electrical responses were displayed in real time. The minimum sound level-evoked CAP was documented as threshold at each frequency from 0.5 to 32 kHz. The CAP thresholds were obtained prior to procedures on the cochlea, after fixing the perfusion inlet catheter and creating the efflux orifice and after scala tympani perfusion.

Gentamicin-Texas Red

GTTR was produced in large batches as described earlier20 and two batches were used at the same relative fluorescence intensity.

Scala tympani perfusion

Perfusion of the scala tympani with artificial perilymph was performed to remove GTTR or gentamicin from the scala tympani following systemic injection, or to infuse aminoglycosides through the scala tympani. An inlet hole (diameter: 70 μm) was made in the scala tympani of the basal turn and the efflux orifice (diameter: 80 μm) at the apex turn of the cochlea. The inlet catheter (MRE-040, Braintree Scientific) with a fine tip (diameter: 60 μm) was inserted into the inlet hole. Tissue glue fastened the tube in position and sealed the inlet hole. GTTR (0.5 mg/ml) and gentamicin (100 mg/ml) were dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride (Baxter Health Corp.) and further diluted with artificial perilymph (in mM: 125 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 0.15 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 5.0 glucose; pH 7.4; 300±10 mOsm) as needed prior to use. Perfusates were infused into the scala tympani for 30 minutes at 2 μl/min using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, PHD 2000) and efflux absorbed using cotton wicks.</title>

Drug delivery

For systemic delivery, 1 mg/kg GTTR (gentamicin base) was injected into the jugular vein, or 200 mg/kg gentamicin intraperitoneally. Serum levels of GTTR or gentamicin, obtained using turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay23 by Lab Services at OHSU (sensitivity: 0.5 μg/ml)7 were ∼7.0 μg/ml (n = 5) or ∼57 μg/ml (n = 3), respectively. Thus, 1.4 μg/ml GTTR or 11 μg/ml gentamicin was delivered by scala tympani infusion (20% of serum level by systemic injection9).

Confocal analysis

After 30 minutes of drug exposure and CAP measurement, guinea pigs were cardiac-perfused with PBS, then 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS. Cochleae were excised and fixed overnight, rinsed in PBS and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for unmasking GTTR fluorescence24 or gentamicin immunolabeling, as follows. Fixed gentamicin-treated cochleae were then immunoblocked in 10% goat serum in PBS for 30 minutes and incubated with 5 μg/ml mouse monoclonal (Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, MA) gentamicin antisera for 2 hours. After washing with 1% goat serum in PBS, specimens were further incubated with 20 μg/ml Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antisera (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), then washed and post-fixed with 4% formaldehyde for at least 15 minutes, as before24. The stria vascularis and organ of Corti from the third coil were excised and whole-mounted in VectaShield (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for confocal microscopy (Bio-Rad MRC 1024 ES).

Imaging and data analysis

Fluorescent images were collected sequentially. Each set of experimental and control tissues were imaged at the same confocal settings. Two sites from the third coil of each cochlea were imaged and identically processed using Adobe Photoshop. High resolution xz optical sections (0.2 μm in z dimension) of the whole-mounted stria vascularis were acquired by confocal image acquisition software. For statistical analysis, GTTR fluorescence intensities were obtained20 for two-way ANOVA (delivery route X GTTR batch) and post hoc t-tests to identify any statistically significant effect of delivery routes. The statistical analysis was performed with Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

References

Forge, A. & Schacht, J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol 5, 3–22 (2000).

Wangemann, P. & Schacht, J. in The cochlea (eds Dallos P.,, Popper A. N.,, & Fay R. R., eds. ) 130–185 (Springer-Verlag, 1996).

Beurg, M., Fettiplace, R., Nam, J. H. & Ricci, A. J. Localization of inner hair cell mechanotransducer channels using high-speed calcium imaging. Nat Neurosci 12, 553–558 (2009).

Marcotti, W., van Netten, S. M. & Kros, C. J. The aminoglycoside antibiotic dihydrostreptomycin rapidly enters mouse outer hair cells through the mechano-electrical transducer channels. J Physiol 567, 505–521 (2005).

Alharazneh, A. et al. Aminoglycosides rapidly and selectively enter inner ear hair cells via mechanotransducer channels. PLoS One 6, e22347 (2011).

Dai, C. F. & Steyger, P. S. A systemic gentamicin pathway across the stria vascularis. Hear Res 235, 114–124 (2008).

Wang, Q. & Steyger, P. S. Trafficking of systemic fluorescent gentamicin into the cochlea and hair cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 10, 205–219 (2009).

Tran Ba Huy, P., Bernard, P. & Schacht, J. Kinetics of gentamicin uptake and release in the rat. Comparison of inner ear tissues and fluids with other organs. J Clin Invest 77, 1492–1500 (1986).

Desjardins-Giasson, S. & Beaubien, A. R. Correlation of amikacin concentrations in perilymph and plasma of continuously infused guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 26, 87–90 (1984).

Greenwood, D. D. A cochlear frequency-position function for several species–29 years later. J Acoust Soc Am 87, 2592–2605 (1990).

Goodyear, R. J., Gale, J. E., Ranatunga, K. M., Kros, C. J. & Richardson, G. P. Aminoglycoside-induced phosphatidylserine externalization in sensory hair cells is regionally restricted, rapid and reversible. J Neurosci 28, 9939–9952 (2008).

Nin, F. et al. The endocochlear potential depends on two K+ diffusion potentials and an electrical barrier in the stria vascularis of the inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 1751–1756 (2008).

Gow, A. et al. Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. J Neurosci 24, 7051–7062 (2004).

Quraishi, I. H. & Raphael, R. M. Computational model of vectorial potassium transport by cochlear marginal cells and vestibular dark cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292, C591–602 (2007).

Hibino, H., Nin, F., Tsuzuki, C. & Kurachi, Y. How is the highly positive endocochlear potential formed? The specific architecture of the stria vascularis and the roles of the ion-transport apparatus. Pflugers Arch 459, 521–533 (2010).

Cohen-Kerem, R. et al. Intratympanic gentamicin for Meniere's disease: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 114, 2085–2091 (2004).

Stepanyan, R. et al. TRPA1-mediated accumulation of aminoglycosides in mouse cochlear outer hair cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol (2011) 10.1007/s10162-011-0288-x.

Dai, C. F., Mangiardi, D., Cotanche, D. A. & Steyger, P. S. Uptake of fluorescent gentamicin by vertebrate sensory cells in vivo. Hear Res 213, 64–78 (2006).

Koo, J.-W., Wang, Q. & Steyger, P. S. Infection-mediated vasoactive peptides modulate cochlear uptake of fluorescent gentamicin. Audiol Neurootol (2011).

Li, H., Wang, Q. & Steyger, P. S. Acoustic Trauma Increases Cochlear and Hair Cell Uptake of Gentamicin. PLoS One 6, e19130 (2011).

Yamane, H., Nakai, Y. & Konishi, K. Furosemide-induced alteration of drug pathway to cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 447, 28–35 (1988).

Higashiyama, K. et al. Bumetanide-induced enlargement of the intercellular space in the stria vascularis critically depends on Na+ transport. Hear Res 186, 1–9 (2003).

Newman, D. J., Henneberry, H. & Price, C. P. Particle enhanced light scattering immunoassay. Ann Clin Biochem 29 (Pt1), 22–42 (1992).

Myrdal, S. E., Johnson, K. C. & Steyger, P. S. Cytoplasmic and intra-nuclear binding of gentamicin does not require endocytosis. Hear Res 204, 156–169 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank Alec Salt and Gregory Frolenkov for constructive discussions, Edward Porsov and Alfred Nuttall for technical support and Qi Wang for synthesizing GTTR. Funded by NIDCD DC04555, DC04555-A2S1 (PSS), R03DC011622 (HL), DC05983 (P30) and by Deafness Research Foundation (HL). The authors would like to thank Drs. Jorge Escobedo and Robert Strongin at Portland State University for molecular modeling (Figure 2c).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL built experimental platform, collected and analyzed the experimental data and prepared the manuscript. PSS conceived the study and edited the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Article File

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Steyger, P. Systemic aminoglycosides are trafficked via endolymph into cochlear hair cells. Sci Rep 1, 159 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00159

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00159

This article is cited by

-

Systemic Fluorescent Gentamicin Enters Neonatal Mouse Hair Cells Predominantly Through Sensory Mechanoelectrical Transduction Channels

Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (2020)

-

In vitro gentamicin exposure alters caveolae protein profile in cochlear spiral ligament pericytes

Proteome Science (2018)

-

Resistance to neomycin ototoxicity in the extreme basal (hook) region of the mouse cochlea

Histochemistry and Cell Biology (2018)

-

Mannitol and the blood-labyrinth barrier

Journal of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery (2017)

-

New treatment options for hearing loss

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.