« Prev Next »

In today’s podcast, Ilona talks to Steve Haddock, a Scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and an Adjunct Professor at UC Santa Cruz. Steve specializes in bioluminescence and gelatinous zooplankton. He recently began a project called Jellywatch, a website for collecting data all around the world about jellyfish sightings. Inspired by widespread misunderstandings about jellyfish blooms and why they happen, Steve and his colleague Katherine Elliott started Jellywatch as a real live database that everyone can participate in, worldwide. Listen to this podcast to learn how Jellywatch is an example of a growing citizen science movement, and how anyone, inside or outside a classroom, can participate. [10:50]

In today’s podcast, Ilona talks to Steve Haddock, a Scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and an Adjunct Professor at UC Santa Cruz. Steve specializes in bioluminescence and gelatinous zooplankton. He recently began a project called Jellywatch, a website for collecting data all around the world about jellyfish sightings. Inspired by widespread misunderstandings about jellyfish blooms and why they happen, Steve and his colleague Katherine Elliott started Jellywatch as a real live database that everyone can participate in, worldwide. Listen to this podcast to learn how Jellywatch is an example of a growing citizen science movement, and how anyone, inside or outside a classroom, can participate. [10:50]

![]()

Full transcript

ILONA MIKO: Welcome to the latest edition of Nature edcast by Nature Education. I'm Ilona Miko, and today we are talking with Steve Haddock from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute about citizen science. Steve Haddock is a scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and an adjunct professor at University of California–Santa Cruz, specializing in bioluminescence and gelatinous plankton. He recently began a project called Jellywatch, a website for collecting data all around the world about jellyfish sightings. Inspired by widespread misunderstandings about jellyfish blooms and why they happen, Steve and his colleague, Katherine Elliott, started Jellywatch as a real live database that everyone can participate in worldwide. Jellywatch is an example of a growing citizen science movement, wherein the public sends in data from any geographical location and participates in research that ultimately helps survey our natural environment on a larger scale than one single research lab is able to do. Steve is also currently finishing a book called, Practical Computing for Biologists, along with his colleague, Casey Dunn. Welcome, Steve.

STEVE HADDOCK: Thanks a lot for having me.

MIKO: Thanks for joining us. Jellywatch has its origins in some research you did in the Google News archive. What prompted you to do this research and what'd you find?

HADDOCK: Well, I work on jellyfish and if you just relied on the news media to understand sort of the world and the environment around us, you would think, you know, shark attacks are on the rise or that jellyfish are taking over the world, because those stories have really popular appeal. And so I think this reliance gives a bit of a distorted picture of what's really going on. And we're interested in this question of whether jellyfish are — are there more jellyfish than there used to be? What's their distribution? And so, I sort of did a search through the Google News archives going back to the early 1900s. It's funny because you can always find people saying, “Oh, we've never seen this many jellyfish before” or “jellyfish are invading our shores by the millions,” and then you look at the date and it's like 1906 or 1952 or something. So it's part of the life cycle of jellies; it's not a new phenomenon. They've been blooming and investing for millions of years because that's sort of how they produce, and so we wanted to basically get data to see if there is evidence that there's been any changes in this population dynamic.

MIKO: So they have an annual cycle of blooming and birthing and dying, but these bigger blooms that seem to get picked up by the news are, you're saying, is also part of a natural sort of meta-cycle?

HADDOCK: Yeah, there's a lot of periodicity to the events. You know, you could have daily changes as the tide goes in and out. You can have annual changes, sort of seasonality, just like you would see, you know, more plants certain times of year every year. But then there's also larger scale cycles going on where maybe every 10 or 12 years you'll have a large event, or you'll have water circulation such that all the jellyfish that are normally offshore are brought on onshore where everybody's, you know, hanging out and swimming.

MIKO: And they're going to attack all the babies on the beach and things like that? [laughter].

HADDOCK: Right. And so, you know, lifeguards probably often work at a beach for five, six, eight years, and so they probably have never seen this before, but if you look back, you know, ten years go, the same thing was going on, in most cases. So partly I think it's just the ubiquity of media now. You know, you can pop up a webpage and find the headlines in any country in the world, so the news travels a lot faster now, too.

MIKO: In the reports that I have seen, it's been attributed to climate change in some way — some temperature change has affected blooms. Is there any evidence to support that?

HADDOCK: There's not a lot of data for that. You know there's lots of factors that people try to attribute jellyfish blooms to — try to say that these are the causes of blooms — and there really aren't that many experiments or scientific studies that support any one of those hypotheses, so —

MIKO: — So we don't really know.

HADDOCK: Yeah, and that's partly what we wanted to do is to try to fill in that gap and say first of all, are they actually increasing, or are we just, you know, have more eyes around the world. And then, what are the potential causes for it?

MIKO: — So how does Jellywatch work?

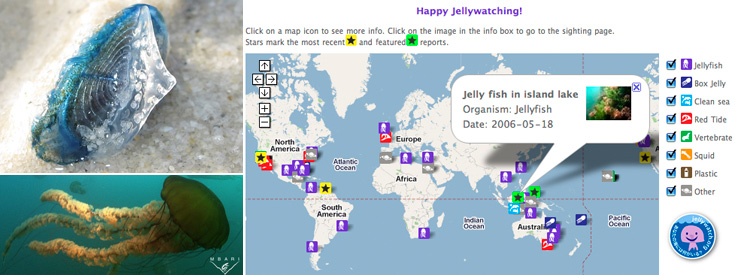

HADDOCK: At its essence, it's a web interface to our database. It's just a webpage that you go to jellywatch.org. You can see a map of all the sightings that people have reported, and then you can report your own sightings as well. And the idea is basically if you were trying to get funding to go out and find all these jellyfish blooms and to monitor them through the years, it would cost millions and millions of dollars and yet we already have people all over the world observing the ocean. I can — there's all these surfers outside my window right now. Those are potential —

MIKO: — data collectors.

HADDOCK: Yeah, deputy data collectors for us. And so we want to tap into that resource basically. People who go out on boats, whale watching or fishing, people who walk the beach every morning — these are great resources because they're basically building up a continuous record of the ocean that's going on around them.

MIKO: And it seems like you get postings far and wide, all over the world.

HADDOCK: It's been really great. I mean we've only really been going for a couple months now, publicly, and we already have from Africa, Europe, South America, Australia, South Pacific, and Indonesia — I mean we've gotten reports from all over the world. We also have a Facebook page. It's sort of accompanies it for discussion and featured sightings and stuff like that, and we've gotten a bunch of fans, from again, just all around the world. So it's really great.

MIKO: So if I'm on the beach in the coast of Africa somewhere, and I see something really interesting, what do I do?

HADDOCK: I mean ideally you would snap a picture of it (even, you know, with a cell phone camera or whatever you happen to have on you) and if you can get to the web, you can go to the website and there's a simple form you fill out. You don't have to register or anything; plug in, you know, this is what I saw; click a little pointer on the map and it will put those coordinates into our database; and then if you have a photo, upload the photo, hit submit, and we will have it in our database.

MIKO: So when you go to Jellywatch, there's a map on the homepage, and that's tracking recent reports?

HADDOCK: Those are all the reports sort of by category, and then the very most recent ones have a little star on them showing some of the featured ones that are especially nice.

MIKO: And then there's sort of a more retrospective database that you're accumulating as well.

HADDOCK: Right. So the other thing that's kind of unique about our site, you know, there's a bunch of sites that are regional in nature for doing similar things, where if you're in the UK or if you're in the Gulf of Mexico or some particular place, then you would email those sightings to somebody there. But the thing about our site that I think is different is that the data — you can download our entire database just with a click — and so it's not like I'm trying to build up my own personal research project. It's a two-way street essentially. And so any of the data that are submitted can be downloaded by researchers or by school groups and other people who are curious about the ocean.

MIKO: So it sounds like Jellywatch has turned into kind of a global research project that's capitalizing on how many people and how often people use the Internet and how it's penetrating into everyone's daily life. So what's the value of something like this? What's the value of having the broader public collect data, outside of just being scientists collect data — what's the value to everyone in general, to education, and to everyone, of a website like this?

HADDOCK: There's a couple different aspects of that I think that make it useful. One is that, I mean the Internet is not just a podium where we sit and deliver lectures from on high about what's going on. It's really a two-way thing. So by having people interact this way with the web, they're providing data and they're also getting the data back. I think it makes them a lot more involved, and hopefully inspires them to sort of care and notice things about the ocean, sort of their ocean. And I feel like it's not our dataset and it's not our ocean, as scientists. There's a lot of these citizen science things going on, and they're really great. There's ones for mushrooms. There's ones for snowfall. There's ones for squirrels. There's bees. There's all kinds of things where researchers are now tapping into this pool of potential data collectors. There's even been papers already that have come out using those kinds of databases.

MIKO: So you think that these things are actually reaching into classrooms? And having some kind of —?

HADDOCK: That's the other hope that we have is that, I mean classrooms could use the data that are already up there to do a project — you know, the jellyfish of Indonesia where they might not normally have real-time data to do that, but they could also have field trips where their own observations end up going into the database and they would feel like they're contributing to the sort of larger scientific effort, in addition to just having that service, the sort of lab notebook for the class.

MIKO: And so it seems like there's broader purposes here. You're into jellies, but it sounds like Jellywatch is really about a lot more than that. So it seems to be about ocean health and you can basically report anything you see. Is that right?

HADDOCK: Yeah. I hope it ends up serving that purpose. We have checkboxes for red tides, for washed up-squids. Sometimes there's reports of these big squid strandings. Kids report trash or marine mammals in distress.

MIKO: Or even a clean area.

HADDOCK: Yeah, clean sea. The important thing, and people always ask me from a scientific context, “Well, that's fine — you get all these people saying there's jellyfish — but how do you know the areas where there aren't jellyfish?” So we want people who are regular beach walkers, for example; they may see jellyfish in the late summer every year, but they may also just go on the beach and not see any. And those sightings are important, too, to just, say, have a time scale of these blooms is happening.

MIKO: Yeah, "no observations" are important. Well, thanks, Steve. That's an interesting project. Thanks for telling us about it.

HADDOCK: Great. Thanks very much.

MIKO: Thank you for listening to this edition of NatureEdcast. You can find this podcast and others at nature.com/scitable. That's nature.com/s-c-i-t-a-b-l-e. Please join us again next time.