-

January 18, 2014

Gallery: The Forgotten Asiatic Lion (And Why Po... -

July 04, 2013

Conservation’s Dark Side: How the Bushmen... -

June 18, 2013

Researchers Use Laser Technology and Find a Lon... -

June 16, 2013

What Happens When Artists Look at the Brain? -

June 13, 2013

A Sunken Egyptian City is Rediscovered, Stunnin... -

June 06, 2013

Why Should We Eat Insects? It’s the Futur... -

May 16, 2013

High School "Citizen Scientists'" Work May Help... -

May 06, 2013

CozmicZoom: An App That Will Humble You As You ... -

April 23, 2013

My Grandfather Is In A Sugar-Apple -

April 19, 2013

The Only Positive Effect Of The Cuban Embargo? ... -

March 22, 2013

The Unhappiest Place On Earth (And How Happines... -

March 14, 2013

Tackling Mental Illness In Africa -

March 05, 2013

The Violent History Of Mauritia: Birth, Oblivio... -

February 19, 2013

Is Global Warming Chiefly Manmade? One Graphic ... -

February 14, 2013

Lovers' Hearts Beat At The Same Rate Everyday -

January 22, 2013

My Med Student Friends Are Zombies: On The Comp... -

January 16, 2013

A Story Of Happy And Sad Endings: On An Afflict... -

October 16, 2012

Fukushima Dogs Had Symptoms Comparable To Post-... -

October 03, 2012

Statistics Is The Sexy In Science -

September 18, 2012

New Smart Light Bulb LIFX Might Just Revolution... -

September 14, 2012

Watch New Footage Of Curiosity Landing On Mars ... -

September 11, 2012

Forget Aeolians, We Need Airborne Wind Farms To... -

August 30, 2012

The Internet Is Not Free: We're In The Filter B... -

August 24, 2012

When A Science Writer Turns His Back On Science -

August 16, 2012

When Peer Review Turns Frustrated Authors Into ... -

August 01, 2012

Chronicling The Coming Of Age Of Two Turtledove... -

July 21, 2012

Soccer's Big Data Revolution -

July 11, 2012

Leap Motion: Death Of The Mouse -

July 04, 2012

Higgs Boson: the jokes edition -

June 29, 2012

A Call To Arms For Young Science Journalists -

June 22, 2012

Your Musical Brain -

June 15, 2012

Science With Religion Can Save More Lives -

June 07, 2012

Keep Cool Science Journalists -

May 24, 2012

Son's Cells Linked To Mother's Cancer -

May 10, 2012

Bat-Robot: From Batman To Reality -

May 08, 2012

That The East Is Rising Is Great (Not Bad) News -

May 03, 2012

The Disorder That Killed One Soccer Player And ... -

April 20, 2012

A Rose By Any Other Name Would Look As Red -

April 13, 2012

My Attempt To Further Promote Young Science Wri... -

March 28, 2012

FuturICT: The Tool That Promises To Predict The... -

March 14, 2012

6 Android Apps For Geeks -

March 02, 2012

Lenses On Biology: Scientists And Science Stude... -

February 24, 2012

A Mauritian At Science Online 2012 -

January 03, 2012

Undressing The Brain With Scale -

December 11, 2011

Love You Melbourne -

November 23, 2011

Funny Things Peer-Reviewers Are Saying Behind Y... -

November 05, 2011

What Is The Place Of New Science Bloggers In To... -

October 27, 2011

Scientists Should Remember That Science Is Much... -

October 22, 2011

Of Kindle, Instapaper and Thesis-ing -

September 04, 2011

Encephalon #90 -

August 07, 2011

Define Science -

July 27, 2011

Your Baby On Crack -

July 17, 2011

Are fMRI Telling The Truth? Role Of Astrocytes ... -

July 08, 2011

15 Mistakes Young Researchers Make -

July 05, 2011

Scientific American's New Science Blogging Netw... -

July 03, 2011

Is Google+ The Google Portal? -

July 02, 2011

Social Media: Getting Content That Interests You -

June 02, 2011

In Science, The More The Merrier -

May 15, 2011

Science Blogs Are Good For You -

May 11, 2011

Medical Research In Australia Is Safe -

May 06, 2011

When The Microscope Goes Digital -

May 05, 2011

In Which I Won A Science Blogging Contest -

April 29, 2011

Science On Royal Wedding Day -

April 22, 2011

The Neuroscience Of Smurfs -

April 14, 2011

Medical Research Funding Cutbacks: Proof That S... -

April 10, 2011

Take A Stance Against Medical Research Cutbacks... -

April 03, 2011

Should Extremely Preterm Babies Be Saved? -

March 30, 2011

Dopamine: The Link Between Neuronal Activity An... -

March 21, 2011

Honors Students Are Newbies -

March 18, 2011

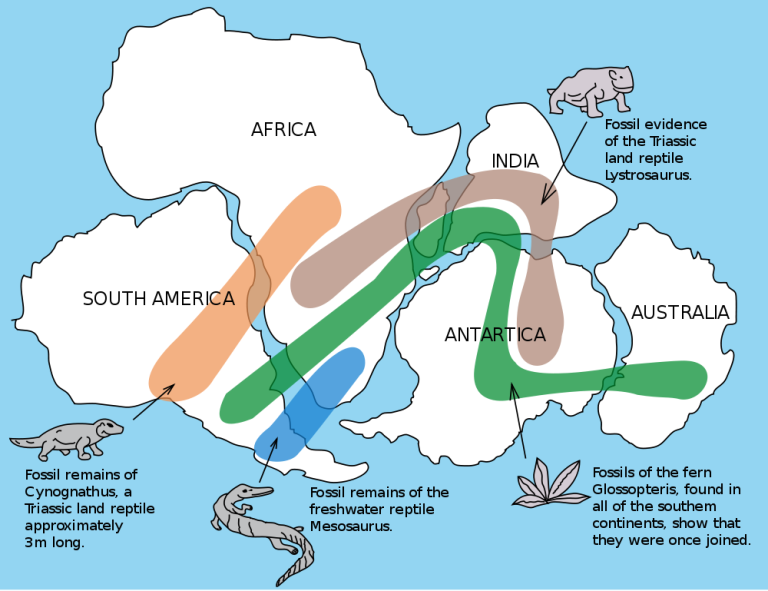

Common Ancestry: We Come From One -

February 25, 2011

Google Teaches Me How To Cook -

February 14, 2011

First Time At The Research Department -

January 31, 2011

Brains Breathe: Dopamine's Role In Preterm Infants -

January 27, 2011

More! More! More! -

January 20, 2011

Building Models: When Science Can Be Fun -

January 14, 2011

An Enjoyable Medical Exam -

January 05, 2011

Application Hassles -

December 29, 2010

The Exam Effect -

December 23, 2010

Welcome, welcome! -

December 20, 2010

In which I help out a researcher...

« Prev « Prev Next » Next »

20 grains of zircons--wow. i don't know much about geoscience methods, but that sounds like some needle/haystack work, no matter how sophisticated your tools are! the nature geoscience paper says beach samples were " sieved and concentrated on location using entirely new equipment."

There is something poetic in such huge conclusions about giant landmasses and millions of years of tectonic plate activity governing their interactions being drawn from such tiny tiny grains of sand.