At a research institute in Hungary not far from the banks of the Danube, an emotional bond began to grow between an elderly night janitor and an old watchdog living there named Balthasar. The dog would sometimes spend the day at the janitor’s home. “Unfortunately, this relationship lasted only a few months, because the janitor became ill ... and eventually died,” writes animal behaviorist Vilmos Csányi, founder of the department of ethology at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, in his book If Dogs Could Talk. Shortly after the janitor’s death, researchers at the institute noticed that Balthasar would disappear from time to time, particularly in the mornings. “We tracked down what he was doing during his absences,” Csányi reports, “and found that he would cross the busy highway, go to his adoptive master’s old house in the village, and sit in front of it for hours.”

Relationships between people and dogs have spawned a myriad of fascinating stories, not least because the association is so improbable. Just take a look at your dog or at any dog in your neighborhood. Would you expect these creatures to be humanity’s best friends? They look very different from us. They behave very differently. They do not seem to have an affinity for culture. And they cannot speak a single word. Yet most people in Western cultures regard their dogs as members of the family in the truest sense. And now behavioral science is starting to reveal how this unlikely friendship came to be.

Almost 20 years have passed since scientific teams led by psychologist Michael Tomasello of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and Csányi in Budapest independently published research papers on how family dogs can follow human pointing gestures to find hidden food. That work marked the birth of a flourishing field of investigation into the biological foundations of the human-dog bond. Since then, researchers have learned that humans and their dog companions live in an attachment relationship, just like mothers and infants. They enjoy one another’s company and find mutual support in potentially challenging circumstances. Attachment relationships also provide the foundation of cooperation: humans help dogs navigate modern society; dogs, in return, help us when we lack a specific ability, such as sight. And when dogs are treated poorly, they sometimes show the same psychological symptoms of an attachment gone wrong that children do.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Research has also shown that dogs have been able to adjust smoothly to family life because of their attentiveness and their sensitivity to human modes of communication and emotional behavior. Dogs tend to express their emotions through vocalization, just as humans do, and they seem to react to the emotional nuances of human speech and cries. Dogs can put on displays of behavior with the canniness of any adolescent to elicit a desired response from their owner. They also excel in learning from humans through observation, which allows them to follow the rules of the family.

The sensitivity of dogs to human emotions means they might also experience stress when their owner is crying. Credit: Getty Images

Now modern technology is extending the human-dog relationship, both by helping us to understand it better and by enabling different forms of interaction. Images of brain activity in humans and dogs show striking parallels in how each species encodes the emotional content of the other’s vocalizations. And devices ranging from state-of-the-art sensors to interactive robots may one day let dogs participate in new cooperative tasks with humans. As we move into an ever more complex future, the ability of dogs to attach and adapt should keep them close by our side.

Fitting In

Dogs are unique in the animal kingdom because they have figured out how to join the community of an entirely alien species—evidence of sophisticated social competence. Psychologists define social competence as the ability of individuals to harmonize their needs and expectations with those of the collective, letting them fit in with the group. Social competence depends on mastering a set of skills, including the abilities to form attachments, regulate aggression, learn and follow rules, provide assistance and participate in various group activities.

Social competence also comes into play when members of a nonhuman species join our social units. So when I design studies of the human-dog relationship with my group at Eötvös Loránd, we focus on the ability of dogs to exhibit each of the components of social competence. In this way, we come to understand their compatibility with us. But a noteworthy question is how dogs were able to develop this competence in the first place.

Anybody who has had the luck or misfortune to raise wolves and dogs at home would agree that the difference between the two is a big one. Wolves do not easily become members of the family, despite all efforts to socialize them to human life. Dogs have been able to bridge the divide because of significant changes in their genes over centuries of domestication, marked by the selection of genetic components that support the development of humanlike social competence when dogs are raised among people.

Attachment for Life

A crucial component of social competence is the ability to form an attachment. Most researchers agree that the attachment between juvenile and adult dogs and their owners closely resembles the bond that exists between mothers and very young children. In the 1960s psychologists John Bowlby of the Tavistock Clinic in London and Mary Ainsworth, then at Johns Hopkins University, developed an intriguing theory to explain the strong tie between mothers and their babies. They argued that this bond, known as attachment, ensures that the baby develops in a safe environment, with opportunities to explore and learn about the complexities of human life.

Ainsworth and her colleagues introduced a simple test that is now the standard method for measuring the quality of this bond in everyday life. Mothers and babies of around 12 to 18 months in age were observed in a series of settings in which the baby was exposed to a strange female or separated from the mother for short periods. The study showed that the babies regarded their mother as a safe base, returning to her from time to time. They also approached her for consolation after being left alone.

It took ethologists many years to recognize that dogs and their owners show this attachment pattern, too. In 1998 animal behaviorist József Topál, then at Eötvös Loránd, and his colleagues asked 51 dog owners to participate in an experiment much like the study of mothers and their babies. The owner and dog were brought to an unfamiliar room and spent some time playing together, first just with each other, then with a toy offered by the owner. Next a friendly stranger entered. The owner left, and the dog spent some time either alone or in the company of the stranger. Somewhat to the surprise of the researchers, most of the dogs behaved like human infants. When the owners were present, the dogs stayed near them and did not attempt to leave the room. Most of the dogs also played readily with their owner. They played less with the stranger, and most stopped playing with the stranger when their owner left. The researchers interpreted this preference as an indication that the dog regarded the owner as a safe refuge in case of potential danger, as attachment theory would predict.

Topál’s team then set out to test whether this behavior represents an attachment relationship with a comparative study of juvenile dogs and wolves. In this experiment, 13 wolves and 11 dogs were separated from their mothers within four to six days of birth and raised by humans until they were four months old. The researchers then conducted the experiment of the stranger and the toy. Despite having the same social experience as the dogs, the wolves did not differentiate between their owner and the stranger, and only dogs used their owner as a secure base. In a parallel study in 2001 animal behaviorist Márta Gácsi of Eötvös Loránd discovered that even adult dogs could develop an attachment relationship with humans, as when an older dog is rescued from a shelter. (As head of the group, I was also on the team for this study and all of the others conducted at Eötvös Loránd.) Thus, the ability to form an attachment relationship with humans is lifelong.

For Better or for Worse

The propensity that dogs show for attachment leaves their relationships with us open to some familiar, humanlike dysfunctions, especially for pets of city-dwelling people. Dogs that a century ago would have had the freedom to wander off and encounter people and other dogs are now often confined to apartments, lonely and with few opportunities to enjoy their time. Most people do well at socializing their dogs, perhaps even without knowing it. But when the owners are neglectful, their dogs, just like infants, are prone to develop separation anxiety. When left alone, these dogs bark excessively, try to escape by destroying walls and doors, and defecate and urinate on the floor.

Dogs that disobey rules—by stealing a sock, say—may appear guilty to their owners but are more likely fearful of punishment. Credit: Getty Images

A 2011 study of this phenomenon conducted by ethologist Veronika Konok and her colleagues at Eötvös Loránd found that when separated from their owner, most dogs stay close to the chair where the owner usually sits. In contrast, dogs displaying signs of separation anxiety do not show a preference for objects touched or left behind by their owner. The researchers concluded that these dogs might have problems associating their owner with his or her home or possessions, so the dogs do not feel safe when their owner is absent.

And just as with distressed infants, anxiety in canines is often an outcome of their caregiver’s personality. In a study published in 2015 in PLOS ONE, Konok and her colleagues reported that owners who show greater degrees of avoidance in their human attachment relationships (say, by not accepting help from others) tend to have dogs with higher levels of separation anxiety. This correlation suggests that behavioral problems in dogs could arise when owners interact with their dogs in an inappropriate way. The owners might not be providing social support when the dog needs it, or they might be absent or negligent when an inexperienced dog is exposed to a social threat. In contrast, a stable and balanced attachment relationship makes dogs feel safe, and it creates a strong emotional bond between dogs and their owners.

Helping tend the flock has long been a canine practical specialty; a modern equivalent is assisting people with physical disabilities. Credit: Getty Images (herding dog and assistance dog);Richard Levine(guide dog)

Emotional Ties

Not least because of this bond, dogs are often admired for their emotional sensitivity, and people living with dogs have always attributed emotions to their animal companions, assuming that dogs are happy, sad, angry and jealous just as humans are. Yet for years academic researchers refused to attribute emotions to animals. That attitude is changing slowly, and nowadays talking about emotions in dogs or other nonhuman species is no longer considered sacrilege.

Today people own dogs just for the pleasure of it, but in earlier times, dogs had to earn their keep by doing jobs such as helping with the hunt. Credit: Getty Images

Still an open question, though, is whether a dog’s emotions signify what we think they do. Although some researchers accept that dog happiness and fear are akin to the human experience, experimental work has shown that dogs and humans differ in emotions of greater complexity, such as guilt. In humans, guilt arises when people violate a social rule, such as stealing someone’s food.

Two independent studies, one led by cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz of Barnard College in 2009 and the other by canine behavioral researcher Julie Hecht, then at Eötvös Loránd, in 2012, examined dogs’ behavior after they were told not to break just such a rule. In Horowitz’s experiment, 14 dogs were told by their owners not to eat food on a table in the living room. The owners then left the room, presumably to give the dogs a chance to obey or disobey. But an experimenter then surreptitiously either offered the treat to the dogs (guaranteeing disobedience) or took it away (guaranteeing obedience).

Next the experimenter reported the dogs’ behavior to the owners, sometimes truthfully, sometimes not, and directed the owners of “obedient” dogs to greet their pets in a friendly manner and to scold dogs they were told had disobeyed. All the dogs that were scolded, whether or not they actually ate the food, displayed in equal measure the behaviors that owners identified as signs of guilt, suggesting that dogs were reacting to the behavior of their owners—that is, scolding and a dissatisfied expression—rather than awareness of their own transgression. Hecht also noted that the dogs’ demeanor was a survival mechanism of sorts, reporting that when asked about their habits at home, owners who observed guilty behavior said they were less likely to scold their dogs after discovering a misdeed.

No definitive research exists on dogs and sorrow, whether they feel their own or react to ours, but psychologists Deborah Custance and Jennifer Mayer, both then at Goldsmiths, University of London, were able to provide scientific evidence for the long-held belief that human crying evokes affiliated behavior in dogs. In a 2012 study, the experimenters observed the reaction of 18 dogs in a home setting as their owners and strangers hummed, talked or pretended to cry. Almost all the dogs approached the crying person, looked at her and touched her. These behaviors were much less frequent when the humans were talking or humming. Although owners may anthropomorphize the dogs’ behavior and believe it to be a sign of empathetic skills, the authors of the study concluded that there is a simpler explanation. They argued that the human cry was similar to distress vocalizations of mammals, including dogs, so the cries evoked distress as opposed to empathy, which would have required the dog to recognize the humans’ inner state.

Supporting this conclusion, a 2014 study led by psychologists Ted Ruffman and Min Hooi Yong of the University of Otago in New Zealand showed that listening to a human baby cry evokes stress in dogs, as revealed by an increase in the levels of cortisol in their blood. Needless to say, when your dog nuzzles you, his behavior is comforting whatever the impetus, but keep in mind that if you are tempted to elicit some affection by showing your sadness, your dog may not be feeling bad for you; he may just be feeling bad because he is stressed out.

Do as I Do!

Much of human culture is based on social learning. Language, the rules of society and the use of objects are all transmitted from the old to the young and from peer to peer. Dogs are very keen to learn by observation, too. The ability to learn socially is widespread among animals, but learning from representatives of a different species is much rarer. Because dogs regard humans as their social companions, their eagerness to learn by observing our activities should not be surprising; shepherds have long known as much. Yet science began probing the depth of this canine facility only in the past five years or so.

One of the most common tests of observational abilities involves a simple detour task, in which a dog must go around a fence of about three meters in length to reach a visible target (such as some food or a toy). In a 2001 study, animal behaviorist Péter Pongrácz and his team at Eötvös Loránd showed that family dogs need six or seven attempts to master this task through trial and error—but they can learn to make the detour after watching an expert dog complete the task only once. And the dogs learned equally well by watching a human expert.

Search-and-rescue dogs are learning to form cooperative relationships not only with people but with machines; one day airborne robots might direct the dogs to the vicinity of a missing person. Credit: Kennan Harvey Aurora Photos

The age-old imitation game that parents like to play with their babies is also helping researchers understand how dogs learn by observing. Mothers and fathers often demonstrate a specific action (such as touching the tip of the nose with their index finger) and then encourage their infant to do the same. In 2006 Topál, then at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and his team were the first to show that people could play a similar game with dogs. A human first trains the dogs to perform three or four tasks (such as turning around, jumping on a table or going around a cone) by demonstrating each of the actions and telling the dog, “Do it!” The dog receives a reward when it completes the task. Most dogs can learn these rules quickly. Then the human demonstrates new tasks (such as touching the cone with a hand). After regular practice, the dogs will naturally imitate such novel actions performed by their human companions.

The do-as-I-do game awakens the natural inclination of dogs to copy our behavior. Yet we do not always wish them to do so. Who wants a puppy to eat from the table, dig in the garden or “read” the newspaper? So humans often discourage dogs from imitating them, and the dogs quickly learn not to copy most activities performed by their human companions. Even so, the number of things dogs learn by watching us might surprise even people who have had dogs for years. Some dogs may learn to open doors by watching their owners turn the handle, or they may jump on a sled just because they see people having fun as they slide down a hillside. Indeed, the ability to learn from observation helps dogs master the rules necessary to fit in with human groups and their owners’ idiosyncratic habits.

Cooperation: Getting Practical

In modern Western society, dogs are often loved just because they are dogs. But dogs would probably not be around today if they had not proved themselves so useful to societies in the past—serving as household alarm systems, protecting the herd from wolves, pulling sledges. And that usefulness continues today as dogs assist the police (with drug detection, say) and help people living with disabilities. Guide dogs for the blind and dogs for people in wheelchairs or living with hearing impairment not only provide round-the-clock practical help but also fill important social roles, of which friendship is one of the most important.

Indeed, a vital element of dogs’ social competence involves their impressive cooperative skills. In a useful partnership, each individual must display self-control, take notice of the other’s goals and actions, and learn to take turns, so that at different times one or the other is in the lead. Studies have shown that guide dogs possess all these skills. In 2001 a detailed behavioral analysis of blind people and their guide dogs, conducted by animal behaviorist Szima Naderi, then at Eötvös Loránd, and her team revealed the fine-grained nature of the interaction as the two walk together, with each partner acknowledging the objectives of the other and switching leadership very rapidly. For example, the blind person initiates a turn to the left or right (because she knows where she wants to go) while the dog takes the lead in evading an obstacle in the street (because the canine can see it).

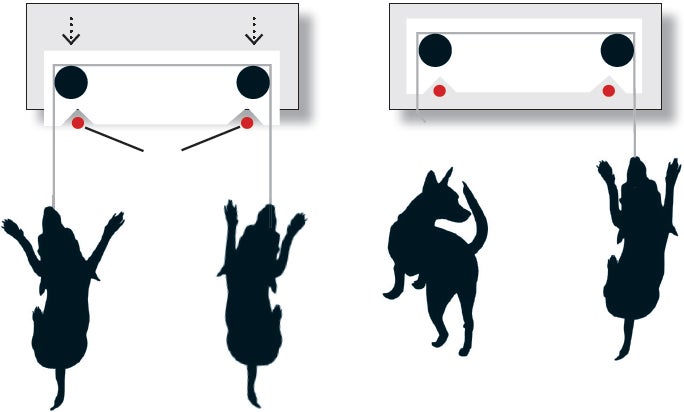

Dogs can also collaborate on tasks in which they seem to understand the consequences of coordinated action. In a study published in 2014, psychologists Ljerka Ostojic and Nicola Clayton, both at the University of Cambridge, reported on dogs’ ability to solve the so-called loose-string task, considered a benchmark test for joint problem solving. In the usual setup, the partners are given a box from which two strings emerge. In fact, they are seeing two ends of a single string. If both partners take an end and pull simultaneously, they will move the target object (placed at the back of the box) to within their reach. If only one tugs at the string, however, it will slip out of the apparatus without moving the prize.

During the experiment, dogs learned to get the prize by coordinating their behavior with either a human or a dog partner. Thus, dogs were able to recognize that the specific actions of the other were necessary for their own success. And this rapid development of cooperative behavior between the dogs and their partners explains why dogs are so good at helping humans in tasks that are narrowly defined, such as leading a sightless person through busy city streets. [For more on how animals work together to solve problems and learn skills, see “The Social Genius of Animals,” by Katherine Harmon Courage].

Dogs in the High-Tech Future

The invasion of modern technology into everyday life may have dog owners wondering how their relationship with their companions will fare in the digital age. Yet dogs have already begun to interact with today’s technology and even to form ad hoc partnerships with devices. In an experiment published in PLOS ONE, animal behaviorist Anna Gergely, then at Eötvös Loránd, and her team delivered some food to family dogs via a remote-controlled car. After a few such interactions, the dogs began to look at, touch or push the car when it was not moving, as if their goal was to get the car to do its “job.” On the surface, the dogs’ actions resembled those they displayed toward their owners in similar circumstances. In principle, if the abilities of devices grow more complex, so should the relationship between dogs and machines.

In the loose-string task, two dogs learn that if they pull together, they can move a treat (red) within reach. But if one pulls and the other does not, the string slips out and the prize is lost. Credit: iStock Photo

Such dog-machine interactions can also have practical benefits. In a project headed by computer engineering professor Bernhard Plattner of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, researchers tested the idea that searches for people lost in the woods or mountains would be more effective if the human rescuers were complemented by a team of dogs and airborne robots armed with cameras. Animal behaviorist Linda Gerencsér of Eötvös Loránd worked with dog trainer Barbara Kerekes to teach four dogs to follow a flying robot over a distance of 100 to 150 meters. They also trained the dogs to stop following the robot and start searching for the missing person by smell if they saw the robot hovering above a specific location. Dogs would then alert the human rescuers by barking if they found the missing person. Researchers believe that as the technology develops, such machine-aided groups will outperform traditional rescue teams, especially if dogs acknowledge the flying robot as a social partner—one to which they might respond with the eagerness they would show to a human companion.

Human life is growing ever more distant from the natural world, and dogs will never be able to understand the breadth of these changes. But their social competence will help them successfully negotiate an evolving society, just as they have since beginning their long journey alongside the human family.

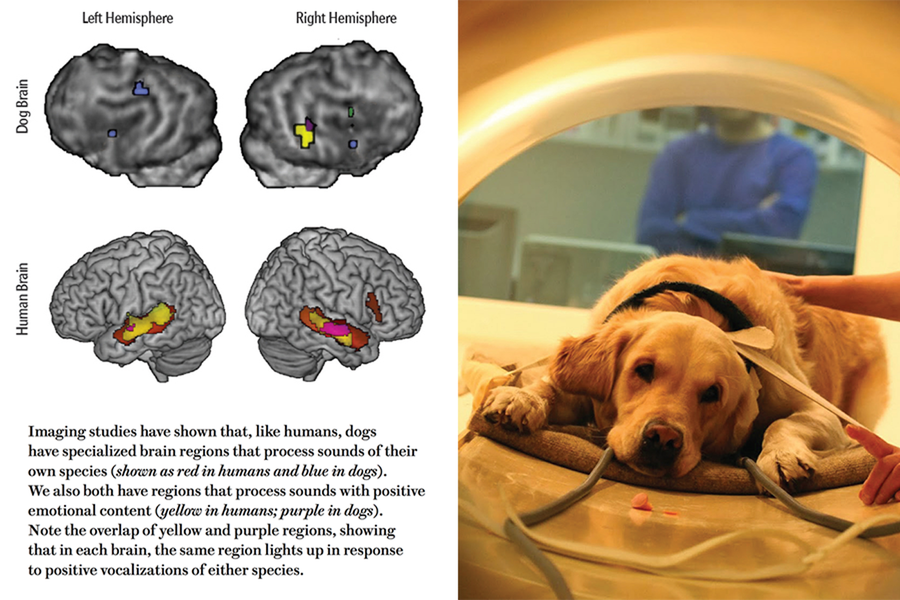

Parallel Brains

Researchers of the human-canine bond have long wanted to see how a dog’s brain reacts to human emotional signals. But the main tool for investigating neural activity—functional magnetic resonance imaging—requires a subject to lie completely still for several minutes. Within the past several years dogs became the first nonhuman species to learn to lie motionless in the apparatus without being physically restrained. On the strength of this breakthrough, in 2014 Attila Andics of the MTA-ELTE Comparative Ethology Research Group in Budapest and his colleagues performed a comparative imaging study of humans and dogs to investigate whether canine and human brains process nonlinguistic acoustic stimuli in a similar way.

Source: “Voice-Sensitive Regions in the Dog and Human Brain Are Revealed by Comparative FMRI,” by Attila Andics et al., in Current Biology, Vol. 24, No. 5; March 3, 2014; Department of Ethology, Eötvös Loránd University (dog in MRI scanner)

Andics’s team recorded more than 100 vocalizations by humans and dogs and asked humans to judge the negative or positive emotional content of the sounds. Twenty-two people and 11 specially trained dogs listened to a long sequence of excerpts from these recordings while their brain activity was recorded. Even though the canine brain is much smaller than the human one, the researchers were able to locate two neural areas that performed similar functions in both species. One area was mostly active when the subjects listened to vocalizations of their own species independent of the emotional content of the voice, showing that dogs and humans each have a brain area in about the same location dedicated to this function.

Even more intriguing was the finding on the processing of emotional information—that human and canine brains have analogous regions where activity correlates with increasingly positive emotional content regardless of the species that produces the sounds. Although these brain areas process acoustic stimuli at a relatively basic level (related, for example, to the length and frequency of the vocalizations), the results provide a preliminary hint of the existence of a neural basis for why family dogs (and sensitive owners) may react so strongly to their companion’s emotions. —A.M.

Decoding the Cat

Felines may be hard to study, but we have learned a few things about them

By Julia Calderone

Cats have a curious allure. Even the most pampered house cats seem to flaunt their independence, as if to say that they do not really need us to get by. Despite this hauteur—or perhaps because of it—many of us cannot resist bringing these regal creatures into our homes, litter boxes and all. In fact, cats outnumber canines as human companions, although we know surprisingly little about their cognition.

Our partnership with cats is long-standing. Feline DNA suggests that the domestic cat may have split from its wild counterpart in the Middle East nearly 10,000 years ago. In 2014 a study by Michael J. Montague, then at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues identified a set of genes that may have been crucial in the transformation of the prehistoric cat into the cuddly pets we know today. These genes have been linked to key behavioral traits, such as the ability to learn and reduced fearfulness, which would have helped cats adapt to life in human company.

Yet many mysteries remain in deciphering feline behavior and intelligence, particularly in contrast to our growing knowledge of dogs. This gap arose in part because of the more urgent need to study dogs. Negative interactions between humans and hostile or misbehaving dogs are common societal problems.

A bigger reason for our poor grasp of the feline mind stems from the challenges of cat behavior. Whereas the ancestors of dogs roamed in packs and learned sophisticated strategies for interacting socially with other animals, the wildcat progenitors of today’s house cats were more solitary animals. The patterns that govern their exchanges with one another and humans are therefore harder to parse. Ádám Miklósi and his colleagues have found that like dogs, cats are able to follow a pointed finger to food, but if the setup is rigged (say, if the bowl is just out of reach), the cat will give up; a dog will creatively strategize or look to humans for help. “If there’s a problem,” says John Bradshaw of the University of Bristol in England, a specialist in human-animal interaction, “cats try to solve it on their own. And if they fail, they just walk away.”

Cats are also tough to manage in the laboratory. “The second you take a cat out of its own home, it becomes nervous,” says Marieke Cassia Gartner, now at the Philadelphia Zoo. If the cat is in its own territory, Gartner continues, it will react more naturally. As a result, most studies of cats are based on observations in the home rather than controlled experiments in the lab.

Given these challenges, we still have much to learn about cats. We can easily decipher a score of signals from dogs, but, Bradshaw says, “with cats, it’s more like five or six.” Some of the signs we know are listed below.

Credit: iStock Photo

PURR

The purr seems to serve multiple purposes: to share emotional states such as happiness or distress; to express urgency, typically when a cat wants to be fed; or to signal stress or injury.

MEOW

Cats generally do not meow at one another, but they learn a repertoire of meows to communicate with humans. Typical meow meanings are specific to a given relationship: an owner knows what his or her cat’s meow means but cannot necessarily understand that of another feline.

EARS

Ears back signals aggression. Ears forward signals interest.

TAIL

Tail straight up shows that the cat is fond of you but also acknowledges that you are slightly superior to it.

Tail straight up and puffed out means the cat is angry.

Tail tucked between legs means the cat is insecure, trying to get away or withdrawing from the world.

RUBBING ITS HEAD AND FACE ON THINGS

A cat has glands on the corners of its lips, between its eye and ear, and under its chin; this behavior marks territory, and some scientists believe it could signal affection.

LYING ON ITS BACK, BELLY EXPOSED

The cat is relaxed and trusts you.

KNEADING

Kittens make this motion to stimulate their mother’s milk. In adulthood, researchers suspect the behavior is affectionate and signals that the kneaded individual is in a superior, mothering role.

LICKING

Cats of the same size and status groom one another frequently, which is thought to improve bonds and eliminate aggression within the colony. “It’s a genuine demonstration of affection,” Bradshaw says, “which in cat societies is very important.”

Julia Calderone is a freelance science writer based in New York City.