Abstract

Study design:

Exploratory qualitative.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to describe the experiences of bowel and bladder dysfunction on social activities and relationships in people with spinal cord injury living in the community.

Setting:

People living with spinal cord injury experiencing bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Methods:

Participants were recruited through the Australian Quadriplegic Association Victoria. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were undertaken with purposively selected participants to ensure representation of age, gender, spinal cord injury level and compensation status. A thematic analysis was performed to interpret patient experiences.

Results:

Twenty-two participants took part in the study. Bladder and bowel dysfunction altered relationships because of issues with intimacy, strained partner relationships and role changes for family and friends. A lack of understanding from friends about bladder and bowel dysfunction caused frustration, as this impairment was often responsible for variable attendance at social activities. Issues with the number, location, access and cleanliness of bathrooms in public areas and in private residences negatively affected social engagement. Social activities were moderated by illness, such as urinary tract infections, rigid and unreliable bowel routines, stress and anxiety about incontinence and managing the public environment, and due to continuous changes in plans related to bowel and bladder issues. Social support and adaptation fostered participation in social activities.

Conclusion:

Tension exists between managing bowel and bladder dysfunction and the desire to participate in social activities. Multiple intersecting factors negatively affected the social relationships and activities of people with spinal cord injury and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secondary health conditions from spinal cord injury (SCI) can significantly reduce quality of life, independence, productivity and can result in poor health outcomes.1, 2, 3, 4 Bowel and bladder dysfunction have been raised as priority secondary health conditions for improvement by people with SCI.5, 6 Following SCI, changes in neurological pathways to the bladder impair its capacity to store urine and alter voiding processes, making urinary tract infections (UTIs) a recurring problem.7 UTIs and other urological complications from bladder dysfunction can cause pain, hospital admissions and compromised kidney function.8 Similarly, neurological control of bowel function is impaired as nerves innervating sphincters and pelvic floor muscles are disrupted by SCI, preventing voluntary control.7 These physical changes can dramatically alter health, usual elimination methods and continence, profoundly disrupting social conventions, activities and relationships.

Few studies have been published which describe the impacts of bowel and bladder dysfunction on social activities and relationships. Some quantitatively designed studies have addressed global and health-related quality of life and bladder management methods or bowel characteristics,9, 10, 11, 12 and methods of bladder management and complications.13 Although these studies did not directly focus on social impacts, those with a social domain within the quality in the life measures reported that people living with SCI may have difficulty initiating new social contacts if dependant,9 or experience social limitation if incontinent.10 Craig et al.,14 however, examined inpatient factors that contributed to social participation following rehabilitation and discharge into the community and found that less severe bladder and bowel dysfunction predicted social engagement. Although a few qualitative studies have explored the experiences of living with neurogenic bladder and bowels, they have been limited to studies of either bowel or bladder dysfunction,15, 16 or the perspective of a particular gender only.16, 17 Further, while barriers to social, leisure, physical and work activities are well-documented consequences of secondary conditions,3, 4, 14, 18 these investigations have not captured the specific nuances of bowel and bladder problems.

People living with SCI can experience diminished opportunities to socialize and develop relationships because of problems such as a lack of financial and transportation resources, poor environmental accessibility, the negative attitudes of others and depression.19 As social engagement and relationships are critical to well-being and quality of life,19, 20, 21 it is important to gain detailed understandings about how bladder and bowel dysfunction impact on social participation. With detailed knowledge on this topic, targeted and proactive interventions can be developed, implemented and evaluated. The aim of this study was to describe the experiences of bowel and bladder dysfunction on social activities and relationships in people living in the community with SCI.

Materials and methods

Participants

This exploratory qualitative study aimed to recruit people living with SCI in Victoria, Australia. Approval for this project was granted by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project number CF15/2994–2015001228). We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. The eligibility criteria for the study were as follows: 18 years of age or over; English speaking; experience with bladder and bowel dysfunction due to SCI; and received most healthcare services within Victoria.

In total, the experiences of 22 participants were captured in the same number of interviews. A carer was present and contributed minor information to one interview. Most participants were funded by Medicare, Australia’s publically funded universal healthcare system (n=12), with others (n=5) funded by the TAC (the state’s ‘no fault’ insurer for road injury) or WorkSafe Victoria (insurer for Victorian workplace injuries), or by other sources (n=5) such as disability pensions, compensation payouts or private insurance schemes. Other participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Procedures

Participants were purposively selected to ensure representation of age, gender, SCI level and compensation status. Recruitment took place through the Australian Quadriplegic Association Victoria, a non-profit organization that offers information and peer support services to paraplegics and tetraplegics affected by SCI. An advertisement about the study and an invitation to participate were distributed by the Australian Quadriplegic Association through their website, Facebook page, fortnightly newsletter and in an e-mail to registered members. Interested people contacted researchers at the university directly by telephone or e-mail. Potential participants were provided with information about the study and emailed a participant and information consent form. Twenty-six individuals expressed an interest in the study and 22 consented to participate. Four potential participants could not be contacted or contacted the researchers after recruitment had closed.

In-depth semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted. Telephone interviews were selected to facilitate access to people living with SCI and to promote free discussion of a sensitive topic. The disadvantage of telephone interviews are that non-verbal communication cannot be assessed and rapport could be more difficult to establish. Consent for participation in the study was audio recorded at the commencement of the interview. Three researchers trained in in-depth interviewing, and knowledgeable about serious injury, performed the interviews using a topic guide (Table 2). The interview topics were designed to comprehensively explore the impacts of bowel and bladder dysfunction on social activities and relationships through multiple and diverse processes. Questions were formulated to examine self-management, interactions with family, friends and community members, as well as health professionals. Interviews took place between September and October 2015 with each interview taking an average of 40 min to complete, and resulting in approximately 15 to 18 pages of transcription. Data saturation was achieved at 22 participants. All the interviews were fully transcribed and loaded into NVivo (Version 10, QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) for data management.

Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using the Framework Method developed by Ritchie and Spencer.22 This framework approach to qualitative data analysis is not aligned with any particular theoretical standpoint. The analysis commenced with repeatedly listening to the data and reading of the transcripts to ensure familiarization. Interviews were inductively coded based on their content and meaning. Groups were formed as repetition and associations among the codes were noted. Using an iterative process, patterns and connection were searched for within and between the groups. Repeated reference was made back to the original research aim to ensure it was fully addressed. This process established a framework of themes and subthemes, which was applied back to the original transcripts for adjustment and to check the scope of its representation. Two researchers (who also conducted the interviews), performed the analysis independently, and regularly met to discuss the developing framework. Inconsistencies were resolved with discussion and minor changes.

Results

Six main themes were identified, some with subthemes as shown in Table 3.

Altered social relationships

The constant need to manage bladder and bowel issues negatively impacted on the initiation and conduct of social relationships.

Role changes

Changes in relationships affected partners as well as other family members and friends, as participants perceived themselves as a ‘burden’ because of their loss of independence in managing bowel and bladder function. The need for assistance with bladder management systems and dealing with incontinence negatively impacted some close personal relationships. Before the SCI, friends or family members would not be involved in toileting, or cleaning up and changing clothes after an episode of incontinence, but since the SCI, family and friends were sometimes called upon to perform these tasks.

‘It causes a lot of stress that gets transferred to my family…At times some of my extended family… because I know they’ve got to witness what I’ve got to do… if I have an accident, I pee my pants and I’m out. I’ve been with my sister-in-law and she’s had to help my wife clean me up. And that’s not what, something that every brother- and sister-in-law have to do together.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #906)

‘My partner’s had to do a lot of extra work, which causes numerous conflict… for example, a bowel accident, that’s all new. I didn’t have bowel accidents before the spinal cord injury… and the bowel accidents have had to be cleaned up by my partner…. A full bag needs to be drained sometimes. My hands haven’t been well so I’ve asked her to drain it, so that impacts… the biggest impact has been on my partner and just drawn us further apart I think.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_18-50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #901)

Dealing with intimacy

A source of concern with intimate relationships was the risk of incontinence. Some participants described being unsure about how best to reveal the realities of bladder dysfunction to a new partner. This issue was difficult to navigate, as it was reported that health professionals failed to discuss intimate relationships and because information available on the topic was scarce.

‘Relationships are very difficult because when do you tell them about it… When you meet a girl and you go out and you hang around with her for a little while, do you tell her straightaway? If you don’t tell her straightaway, the anxiety starts to build about it, about the sexual dysfunction, about pee bottles and going to the toilet.’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #908)

Some participants reported their complex bowel and bladder issues made relationships too difficult. The presence of permanent catheters in the body reduced participants’ confidence in the way they looked, and produced negative attitudes from some partners.

‘And I don’t think I’d ever get into... I don’t think I’ll be able to get into a relationship now, I just feel it’s a putting off thing…. And the way I look at it is if I do get close to someone and there is going to be a sexual thing involved, if I pull down my pants …I’d be just put off….I had a relationship when this happened to me. He was very good, he stayed around for... we broke up two years ago when this bowel thing started happening. I spoke to him a couple of months ago, but if he knew I had a catheter and all that in me now, my god, he’d run the other way.’

(Female_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #914)

Keeping it personal to support social relationships

Although it was not always possible to keep bowel and bladder dysfunction private, such as when assistance was required or incontinence occurred, most participants reported their preference for keeping this information private. Thus, despite the considerable impact of bowel and bladder dysfunction on their daily lives, information about this issue was only shared with friends and family if participants perceived it to be necessary.

‘Firstly, most of them wouldn’t have a clue, that’s something that I know about but they don’t know about, and I probably wouldn’t share it... well, I would share it with them if I thought it was relevant but I certainly don’t specifically need to.’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #921)

While desiring privacy, participants also wanted greater understanding from friends about such SCI issues. This tension caused frustration, as participants did not feel comfortable with revealing the significant daily challenges faced with managing bowel and bladder dysfunction that were largely responsible for their variable attendance at social activities.

‘And the bowel and bladder issues are the most debilitating and the most important as far as managing the spinal cord injury…. Generally, people don’t understand that at all. And you don’t feel like enlightening them.’

(Female_paraplegic_incomplete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #920)

‘People don’t get it. They don’t understand. You just have to come to terms with the fact that your friends just don’t understand how hard it is for you, and you have to just suck it up, really, just get on. It’s just something that, I don’t know, no-one really understands.’

(Female_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #909)

Lack of adequate bathrooms is a social barrier

Social interaction outside the home was affected by available bathroom facilities. When access to and the location of disabled public bathroom facilities was unclear, it influenced the type of activities undertaken, enjoyment of the activity and the length of activity engagement outside the home. Significant uneasiness arose for participants when access to bathrooms was restricted, such as in private residences.

‘Most of my friends are in (name of area), but the few friends that are here, their houses aren’t accessible, or if they are, their toilets aren’t. I can get in the house but I can’t get in the loo, so I have to take a bottle with me. I empty my catheter into the bottle and then get someone to tip that in the toilet for me, it’s embarrassing.’

(Female, paraplegic_ complete_>50yrs_6-15yrs post-injury_non-compensable_ #909)

Inaccessible bathrooms at private properties also impeded the establishment of new relationships and affected the maintenance of existing relationships.

‘I can’t stay with my... I’ve got a son and daughter-in-law and a little grandchild... I can get into the house, I can’t get into the toilet or the bathroom. So I can’t stay with them. So I don’t often see my grandchild because of that.’

(Female_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #909)

Strain in relationships also developed when public disabled bathrooms were difficult to find and enter.

‘The built environment, it’s not made for people in chin controlled electric wheelchairs that can only move around and go certain places, to manage you better and bladder and bowel when you’re out. It causes a lot of stress that gets transferred to my family and that. It restricts me from doing things at times.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #906)

Social support and networks promote social participation

Social activities were facilitated when participants had good social supports, as bowel and bladder dysfunction were perceived to be more manageable. Social support, such as physical and emotional support and advice, arose from different sources of social networks including partners, family, friends, carers and peer supports.

‘Probably the biggest of all is carer support, without that I’d be useless. Plus a lot of emotional support from family and friends.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_18–50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #901)

For some, social activities were only possible when carers were available to assist with managing bowel and bladder dysfunction. Inadequate carer support was reported as a major barrier to social engagement outside the home.

‘My carers are very good. If I didn’t have them I don’t know what I would do because there is no way I can change myself. And when I do go away, like I said, with this girlfriend now, I have to take a carer with me, because I just can’t do things on my own – all the changing stuff.’

(Female_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #914)

In seeking support and advice to manage bowel and bladder dysfunction, some participants reported new friendships and alliances through SCI peer networks. Peer and advocacy organizations promoted networking among people with SCI, and were identified as valued sources of information. Information shared at these meetings provided practical advice from those with experience in managing bladder, bowel and SCI problems.

‘I always talk with my friend, the spinal cord injured friend. We have a network, like all friends, spinal people. We all get the same things.’

(Male_paraplegic_incomplete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #917)

Moderated social activities

Participation in social activities was profoundly reduced and disrupted by illness, stomach upsets, routines for regular bowel function and stress and anxiety about managing outside the home. Constant changes in social plans and emotional reactions eventuated.

Daily routines

Routines to manage bowel dysfunction were reported to be inflexible and time consuming. This meant social activity was required to fit around non-negotiable bowel schedules.

‘Well, it usually means if I want to go out... if I want to stay somewhere overnight, like at my girlfriend’s, if I want to stay I have to work out if the next day is a bowel day, I really should be at home, that’s kind of how it impacts.’

(Female_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #910)

Strict bowel routines, however, did not guarantee reliable attendance at social occasions.

‘And, certainly, my bowels would be the chief call on me not going to functions I think. If my bowels go badly I’m a bit loathe to going out to have bowel actions, so I’ll not go out.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #904)

Stress and anxiety

Most participants described embarrassing situations when management of their bowel and bladder dysfunction had failed. The aftermath of such incidents was stress and anxiety about engaging in future social activities.

‘If they’re not going the way they’re meant to, it affects your social life in a big way. If your bowels have been playing up that means you’re going to hesitate about planning activities. You might need to stay at home, close to your bathroom for a week or until it settles down, so it can completely stop for a period of time. If you have a bowel accident or your condom comes off and you get wet while you’re away, if you’re out with friends and stuff like that. And next time, that will make you think what if it happens again? You might stop going out.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #915)

To alleviate stress and anxiety about potential bowel and bladder accidents, the participants limited their travel to familiar local areas, reduced the number of activities in which they engaged, and developed a preference for staying at home. These restrictions also diminished opportunities for spontaneous social activity.

‘…because it’s one of the things that if you can’t control your bladder, and you piss all the time, it’s one of the things that stops you from wanting to go anywhere. You’ll travel locally around here, where you can keep everything under control, but if somebody said to you do you want to come for a trip to Sydney with me, managing your bowels and your bladder and all that sort of stuff, you just go ‘No’.’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #908)

Negative emotions and a reduction in the enjoyment of social activities resulted from the ever-present concern of bowel and bladder accidents and the embarrassment when they did occur.

‘It’s always a concern of having a bowel accident. Yeah, that doesn’t go away… it brings me down knowing that I’m vulnerable to at any time having accidents… There have been times when I’ve been out and I’ve had a bowel accident and just everything else that comes through that, having to be cleaned up, having to leave the premise or leave where I am, having literally come and clean the mess up that’s been created, the whole mess, mentally and physically.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #923)

Participants described missing out on particular social activities to be disappointing, upsetting and stressful.

‘It just makes you feel pretty shit sometimes because … it might be somewhere where you really wanted to go, something that you’re really looking forward to you can’t do, you can’t go or whatever.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #915)

In a negative cyclic pattern, bowel and bladder problems reduced confidence in, and reinforced stress and anxiety about, social activities.

‘Last year my son got married and I was stressing out about that for a year, as to how I’m going to cope on the wedding day…. Anyway, they got married and most of the family and friends stayed the night. My cousin stayed with me in the room… I was in pain, in the middle of the night I started feeling sick…. I had the catheter in but every time I was urinating it was just killing me, it was really hurting… Every time I do something there’s always a problem.’

(Female_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #914)

‘It’s very inconvenient when you have a bowel accident, after not having a successful time in the bathroom. It doesn’t give you the confidence to do anything or go anywhere.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_6-15yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #907)

Changing plans

Participants reported performing daily assessments of their capacity to engage in social activities. Changes in social plans were attributable to illness, stomach upsets, a lack of carers to manage bowel and bladder issues, episodes of incontinence and problems with bladder management equipment.

‘I’ll tell you now that affects everything in your day because if things aren’t working, or you’re on the way to an appointment and you have a bowel accident, well, guess what, the whole day’s ruined and everything is cancelled. So day-to-day life is impacted by bowels and bladder in particular. And throw pain into the equation as well.’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #918)

When participants were hospitalized or housebound due to feeling unwell from UTIs or stomach upsets, social activities were put on hold. As many participants experienced frequent episodes of illness, periods of social isolation were common. Social isolation was self-imposed as most participants stated their preference for no visitors when bedbound or hospitalized, and most did not want the burden of socializing when feeling unwell.

‘If I’m not feeling well I don’t go out, you stay home. Or if you’re in hospital or you’re sick or you’re on antibiotics or whatever, well, then you tend to be more isolated because you don’t go out… They all impact on how you are as a person, because when you’re unwell, you’re not the same person that you are and if you’re sick or tired you can’t do the things that you normally would do, so it has a huge impact… Because when I get a UTI I’m really unwell.’

(Female_paraplegic_incomplete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #920)

Even when participants were feeling well, bowel and bladder issues significantly altered their participation in social activities. Attendance at planned activities were frequently delayed, cancelled, shortened or not arranged. Accordingly, participants could not guarantee their presence at social events.

‘And if you do have a problem, whether your condom comes off or you have a bowel action that means either you just have to cancel it or you’re going to have to go late. So sometimes my friends will think I’m not reliable because of that.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #915)

Adaptation for social engagement

Although the management of bowel and bladder dysfunction consistently raised challenges for participation in social activities, some, but not all, participants reported making psychological and lifestyle adjustments to minimize their impact.

Acceptance

A number of participants reported a level of acceptance about the daily bowel and bladder issues they encountered and their impacts on social activities. Reaching acceptance entailed a positive attitude, prioritization of activities, formulating a plan to manage the problem and being flexible with social plans.

‘You’re restricted with the pain you get from the bladder pain or the autonomic dysreflexia… It takes a bit away from my social life. I like to be able to get out and do things at night now, but now I’ve got to go and see movies, or matinees or things in the afternoon. That’s okay… you’ve got to make it work.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #911)

Modified diet

To reduce the anxiety, stress and embarrassment associated with unplanned bowel actions, participants reduced their intake of food, consumed specialized diets and confined their meals to a certain time of day. Controlled food consumption instilled confidence in participants to engage in social activities without experiencing unplanned bowel actions.

‘I eat lots of fruit, I try not to eat too much crap at night. I may just even have a bowel of veggies for dinner, which I hate. But it’s good for the bowels and I really don’t want to have bowel accidents while I’m out, say, in the car or visiting friends or something like that because it’s not pleasant.’

(Male_tetraplegia_incomplete_18-50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #901)

A restricted diet was also considered beneficial for reducing the incidence of UTIs.

‘Bladder infections are a problem. You’ve got to watch your diet, that’s probably the biggest thing that affects it. No dairy products, or keep them down to a bare minimum. Not drinking too much beer, that dehydrates you. Chocolate is an enemy because of the sugar.’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #908)

Although controlled food consumption assisted with adherence to bowel routines, it also had the potential to create awkward social situations.

‘At work and stuff, if there’s a morning tea or they throw an afternoon tea… and I refuse to eat any of the cupcakes or the food and people are like ‘Why? Go on have a cupcake’. ‘It’s not part of my routine.’ ‘Why?’...’ I won’t go into details and say if I eat this cupcake I’ll probably have a bowel accident without any warning. I don’t ever go into that nitty-gritty.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #919)

Planning

Some participants made plans in an effort to reduce potential issues or to be prepared to deal with problems should they arise.

‘If my guts are playing up and stuff like that, and I think maybe if I go out, if I push my wheelchair or to play sport, it could happen, so I just won’t attend; I won’t go… or sometimes you’ve just got to come up with plans. So if you’re out you might have to leave early, just to reduce the risk.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #915)

‘You plan for things now. I’ve always got a spare set of clothes and a change of clothes in the car…’

(Male_paraplegic_complete_18-50yrs_ ⩽ 5yrs_post-injury_compensable_ #918)

Preference for home

To balance the complexities of managing bowel and bladder dysfunction in the built environment, with the desire to participate in social activities, some participants preferred people to visit them in their home environment.

‘I’ve got (number of) sisters and they all live nearby and I’ve got lots of friends. I’m a very social person, I just don’t go out much. But I’ve sort of created an environment around me where everyone who knows me know they’re welcome to come and see me, and they also understand it’s much easier for them to come to me than me to come to them. So I just have that network of people that do that.’

(Male_tetraplegia_complete_>50yrs_ ⩾ 16yrs_post-injury_non-compensable_ #912)

Discussion

This study highlights the diverse challenges to social engagement that stemmed from bowel and bladder dysfunction and their associated complications following SCI. Although participants coveted privacy and control over bowel and bladder dysfunction, this was often unachievable, and profound changes in relationship and social activities occurred. Reduction in social engagement can reduce access to social support and lessen opportunities for social activities and relationship development, potentially compromising physical and mental health and well-being.19, 20, 21 To optimize social connections and participation, targeted interventions to improve management of and coping with bowel and bladder dysfunction could benefit people living with SCI.

Undertaking social activities outside the home was moderated by multiple factors, of which a key consideration was the risk of bowel and bladder incontinence. Consistent with other studies, participants felt stress and anxiety about the risk of uncontrolled bowel motions and bladder accidents12 and wanted to keep information about the issue personal.23 Concern about incontinence impeded social activities outside the home17, 24 and any episode that did occur incited further stress, and added to feelings of embarrassment and vulnerability. Further, most participants did not want to alter social relationships by asking family or friends for assistance with toileting, emptying bladder management systems, or changing clothes, which limited the times for, and types and places of, social activities. Such requests were perceived to push normal social boundaries and overstepped the role of family and friends.

These findings suggest the need for health professional involvement for people with SCI to manage the psychological and emotional consequences of bowel and bladder dysfunction. Counselling could assist with adaptation strategies by addressing difficulties with asking for and receiving help, emotional reactions to bowel and bladder accidents, managing others’ attitudes, dealing with changes in body image, and coping with strained social relationships.25 Regular contact with a continence/urological nurse consultant could also be of benefit.26 This could insure that people are linked to the appropriate contacts to discuss issues, assess current bowel and bladder management practices, and receive ongoing support, education and up to date information. Specifically, optimal bowel and bladder management could be achieved, assisting to mitigate this barrier to participation in social activities.

A complex relationship exists between the environment, disability and participation in social activities and relationships for people living with SCI.27 Environmental factors impeded independence and social activities when issues were encountered with the attitudinal, social and physical environment. Societal attitudes have been previously noted as a barrier to social participation for people living with SCI,19, 27, 28, 29, 30 but not in the context of bowel and bladder dysfunction. Previous studies have not addressed the negative attitudes and perceived judgement from others about bowel and bladder incontinence and the use of equipment (such as permanent catheters) to manage the dysfunction reported in our study. However, previous research has highlighted poorly functioning close relationships and difficulty commencing new relationships due to bowel and bladder dysfunction.9, 28 The built environment impeded social activities and the enjoyment of them because of poor access to, and a lack of, adequate disabled bathrooms. This is of particular concern given Australian federal legislation (Disability Discrimination Act 1992) exists about access to disabled toilet facilities31 and the issue has been previously well reported.12, 17, 29, 32, 33 Access to private property and bathrooms has also been reported as a social limiter.29

As environmental barriers are often interconnected and cumulative,27 a multidimensional approach could lessen their existence. To facilitate health, dignity, independence and participation in social activities, the lack of adequate disabled bathroom facilities in the public environment needs to be improved.32, 33 By working in collaboration with people with SCI, council planners, business owners and designers of public spaces can address barriers to disabled bathroom access and use, as well as other physical barriers in the environment to social activities. To address attitudinal barriers, education to increase societal awareness about SCI and secondary problems is needed, as well as the importance of participation in social activities. To improve the social environment, mental health support services specialized in dealing with SCI need to be accessible to prevent significant strain on relationships with partners and families, avoid social isolation and lessen stress and anxiety about engaging in social activities.17 In addition, an enabling social environment can be fostered through adequate formal care provision, which can prevent partner or family relationships from becoming overburdened with informal care duties.15, 18, 28 Sufficient paid carer support could lessen the burden of having to ask friends and family for assistance with personal body functions, and promote confidence in social activities.

The provision of social support and good social networks also positively influenced the social environment. Social support is known to buffer the impacts of health stressors and positively assist with managing stress.34 In our study, some social relationships facilitated the daily management of bowel and bladder dysfunction, thereby removing some of the challenges involved in social engagement. Increased social participation can expand social networks, which can in turn increase support for the management of bladder and bowel function.18 Our study also reported that social activities were fostered by peer support providing information about managing bladder and bowel function, suggesting that this relationship could be a beneficial resource for expanding social networks, supports and promoting adaptation.28, 29, 35 These results highlight the need to comprehensively understand the diverse impacts of environmental influences on managing bowel and bladder dysfunction and social activities, as much as the mechanics of elimination in SCI.

To deal with the tension between social engagement and managing bowel and bladder dysfunction, participants described an ongoing process of adaptation. Participants exercised autonomy over variables within their control to mitigate this conflict, consistent with an ‘engagement’ coping strategy used for adjustment to living with SCI.36 In our study, engagement strategies included acceptance, planning and problem solving (such as modified diets). However, adaptation to bowel and bladder dysfunction in our results revealed acceptance of issues and adjustments to work around them, rather than the need to accept a method of bladder management as suggested by Shaw and Logan.37 Although adaptations enabled social participation, they restricted the times and places social activities could occur. Such compromise emphasizes the importance participants attached to managing bowel and bladder dysfunction to achieve maximal independence for social engagement.25 It also highlights the continued need to research ways of managing bladder and bowel dysfunction, as this is a priority issue for people living with SCI,5, 6 and little research has been conducted in this area.38

The development of UTIs negatively impacted on social activities. UTIs were a constant cause of unstable health, necessitating significant changes in social plans and self-imposed isolation. Although UTIs are among the most frequently experienced secondary conditions,39, 40, 41 the impact of UTIs on social activities has been largely unaddressed. Our findings are in contrast to those of Barclay et al.19 who reported that physical health issues in people living with SCI were not a barrier to social and community participation. This difference may be explained by their sample containing a higher proportion of those with partners, or due to varying bladder management methods that were not reported. Overall, these results draw attention to the need for development of new technologies and process for managing bladder dysfunction and preventing urinary and bladder infections.

Limitations

Limitations to this research exist. Some participants reported difficulty in separating bowel and bladder issues from other issues associated with their SCI, perceiving them all to be interconnected. It is possible that people with a particular interest in or experience with bladder and bowel dysfunction and UTIs were more likely to participate in this study. We interviewed English speaking people only, and therefore it is possible that those with a language other than English may hold varying perspectives. We recruited participants through the Australian Quadriplegic Association Victoria, which predominately relied on the electronic distribution of information for the research project. Thus, those not connected to the Australian Quadriplegic Association or its linked partners, or those without Internet connection, are unlikely to have had the opportunity to participate in the study.

Conclusion

The findings from this study highlight the tension between managing bowel and bladder dysfunction and the desire to participate in social activities. Multiple intersecting factors negatively affected the social relationships and activities of people with SCI and bowel and bladder dysfunction, in particular health, psychological and emotional states, and the attitudinal, social and physical environment. Improvement in all these areas could lessen the negative social impacts for people with SCI living in the community. To potentially promote participation in social activities and relationship development for people with SCI and bowel and bladder dysfunction, a suggested future direction could be to focus on the provision of social support and evaluate other supportive interventions. A further suggestion to promote health and lessen social impacts, could be to broaden techniques that manage continence and reduce infections.

DATA ARCHIVING

There were no data to deposit.

References

Barker RN, Kendall MD, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ, Haines TP, Kuipers P . The relationship between quality of life and disability across the lifespan for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009; 472: 149–155.

Shaw C, Logan K, Webber I, Broome L, Samuel S . Effect of clean intermittent self-catheterization on quality of life: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2008; 616: 641–650.

Guilcher SJT, Craven BC, Lemieux-Charles L, Casciaro T, McColl MA, Jaglal SB . Secondary health conditions and spinal cord injury: an uphill battle in the journey of care. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 3511: 894–906.

Callaway L, Barclay L, McDonald R, Farnworth L, Casey J . Secondary health conditions experienced by people with spinal cord injury within community living: implications for a National Disability Insurance Scheme. Aust Occup Ther J 2015; 624: 246–254.

Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JTC, Wolfe DL Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Research Team. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2012; 298: 1548–1555.

Hammell KRW . Spinal cord injury rehabilitation research: patient priorities, current deficiencies and potential directions. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 3214: 1209–1218.

Francis K . Physiology and management of bladder and bowel continence following spinal cord injury. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007; 5312: 18–27.

Fonte N . Urological care of the spinal cord–injured patient. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2008; 353: 323–331.

Hicken B, Putzke J, Richards S . Bladder management and quality of life after spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 8012: 916–922.

Liu CW, Attar KH, Gall A, Shah J, Craggs M . The relationship between bladder management and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury in the UK. Spinal Cord 2010; 484: 319–324.

Pardee C, Bricker D, Rundquist J, MacRae C, Tebben C . Characteristics of neurogenic bowel in spinal cord injury and perceived quality of life. Rehabil Nurs 2012; 373: 128–135.

Naicker AS, Roohi SA, Naicker MS, Zaleha O . Bowel dysfunction in spinal cord injury. Med J Malaysia 2008; 632: 104–108.

Cameron AP, Wallner LP, Forchheimer MB, Clemens JQ, Dunn RL, Rodriguez G et al. Medical and psychosocial complications associated with method of bladder management after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 923: 449–456.

Craig A, Nicholson Perry K, Guest R, Tran Y, Middleton J . Adjustment following chronic spinal cord injury: determining factors that contribute to social participation. Br J Health Psychol 2015; 204: 807–823.

Burns AS, St-Germain D, Connolly M, Delparte JJ, Guindon A, Hitzig SL et al. Phenomenological study of neurogenic bowel from the perspective of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 961: 49–55.

Engkasan JP, Ng CJ, Low WY . Factors influencing bladder management in male patients with spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Spinal Cord 2014; 522: 157–162.

Nevedal A, Kratz AL, Tate DG . Women's experiences of living with neurogenic bladder and bowel after spinal cord injury: life controlled by bladder and bowel. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 386: 573–581.

Guilcher SJ, Casciaro T, Lemieux-Charles L, Craven C, McColl MA, Jaglal SB . Social networks and secondary health conditions: the critical secondary team for individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2012; 355: 330–342.

Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P, Bourke-Taylor H . Facilitators and barriers to social and community participation following spinal cord injury. Aust Occup Ther J 2016; 631: 19–28.

Saunders LL, Krause JS, Focht KL . A longitudinal study of depression in survivors of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2012; 501: 72–77.

Cohen S . Social relationships and health. Am Psychol 2004; 598: 676–684.

Ritchie J, Spencer L . Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R (eds) Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge: London, UK. 1994, pp 173–194.

Koch T, Kralik D, Kelly S . We just don't talk about it: men living with urinary incontinence and multiple sclerosis. Int J Nurs Pract 2000; 65: 253–260.

Burns A St, Germain D, Connolly M, Delparte J, Guindon A, Hitzig S et al. Neurogenic bowel after spinal cord injury from the perspective of support providers: a phenomenological study. PM R 2015; 74: 407–416.

Van De Ven L, Post M, De Witte L, Van Den Heuvel W . Strategies for autonomy used by people with cervical spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 304: 249–260.

Logan K, Shaw C . Intermittent self-catheterization service provision: perspectives of people with spinal cord injury. Int J Urol Nurs 2011; 52: 73–82.

Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Gray DB, Stark S, Kisala P et al. Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: a qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 964: 578–588.

Munce SE, Webster F, Fehlings MG, Straus SE, Jang E, Jaglal SB . Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 48.

Price P, Stephenson S, Krantz L, Ward K . Beyond my front door: the occupational and social participation of adults with spinal cord injury. OTJR 2011; 312: 81–88.

Dickson A, Ward R, O'Brien G, Allan D, O'Carroll R . Difficulties adjusting to post-discharge life following a spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol Health Med 2011; 164: 463–474.

Australian Human Rights Commission. A brief guide to the Disability Discrimination Act: Australian Human Rights Commission; 2016 [cited 13 April 2016]. Available from: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/guides/brief-guide-disability-discrimination-act.

Wilde MH, Brasch J, Zhang Y . A qualitative descriptive study of self-management issues in people with long-term intermittent urinary catheters. J Adv Nurs 2011; 676: 1254–1263.

Vaidyanathan S, Soni BM, Singh G, Oo T, Hughes P . Barriers to implementing intermittent catheterisation in spinal cord injury patients in Northwest Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, Southport, UK. ScientificWorldJournal 2011; 11: 77–85.

Cohen S, Wills TA . Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985; 982: 310–357.

Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A, Gordon S . Using peer mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J Clin Nurs 2011; 203-4: 351–358.

Livneh H, Martz E . Coping strategies and resources as predictors of psychosocial adaptation among people with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 2014; 593: 329–339.

Shaw C, Logan K . Psychological coping with intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) in people with spinal injury: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 5010: 1341–1350.

Coggrave M, Norton C, Cody JD . Management of faecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1: CD002115.

Adriaansen JJ, Post MW, De Groot S, Van Asbeck FW, Stolwijk-Swuste JM, Tepper M et al. Secondary health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study from one to five years post-discharge. J Rehabil Med 2013; 4510: 1016–1022.

D'Hondt F, Everaert K . Urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injuries. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2011; 13: 544–551.

Jensen MP, Truitt AR, Schomer KG, Yorkston KM, Baylor C, Molton IR . Frequency and age effects of secondary health conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Spinal Cord 2013; 5112: 882–892.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Trethewey and express our appreciation to the participants. This project is funded by the Transport Accident Commission through the Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research. BG was supported by a Career Development Fellowship (GNT1048731) from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braaf, S., Lennox, A., Nunn, A. et al. Social activity and relationship changes experienced by people with bowel and bladder dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 55, 679–686 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.19

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.19

This article is cited by

-

Priorities, needs and willingness of use of nerve stimulation devices for bladder and bowel function in people with spinal cord injury (SCI): an Australian survey

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2024)

-

Experiences of people with spinal cord injuries readmitted for continence-related complications: a qualitative descriptive study

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Social Ecology of Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2024)

-

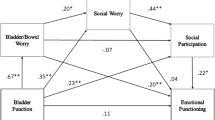

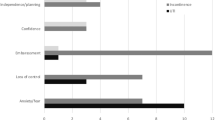

Bladder and bowel function effects on emotional functioning in youth with spinal cord injury: a serial multiple mediator analysis

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Neuromodulation Following Spinal Cord Injury for Restoration of Bladder and Erectile Function

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2023)