Abstract

Study design:

Cross-sectional.

Objective:

The objective of the study is to examine whether alcohol use disorders should be conceptualized categorically as abuse and dependence as in the 'Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders' 4th edition or on a single continuum with mild to severe category ratings as in the 'Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders' 5th edition in people with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

United States of America.

Methods:

Data from 379 individuals who sustained SCI either traumatically or non-traumatically after the age of 18 and were at least 1 year post injury. Rasch analyses used the alcohol abuse and dependence modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP).

Results:

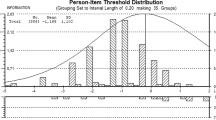

Fifty-seven percent (n=166) of the entire sample endorsed criteria for alcohol abuse, and 25% (n=65) endorsed criteria for alcohol dependence. Fit values were generally acceptable except for one item (for example, alcohol abuse criterion 2), suggesting that the items fit the expectation of unidimensionality. Examination of the principal components analysis did not provide support for unidimensionality. The item–person map illustrates poor targeting of items.

Conclusions:

Alcohol abuse and dependence criterion appear to reflect a unidimensional construct, a finding that supports a single latent construct or factor consistent with the DSM-5 diagnostic model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, between 250 000 and 500 000 people sustain a spinal cord injury (SCI) annually, and the primary causes of SCI are motor vehicle collisions, falls and violence.1 Preinjury alcohol use problems have been identified as a common comorbid condition associated with SCI as well as obstacles to rehabilitation (for example, see refs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Given that alcohol problems are common and potentially disabling in persons with SCI, it is important to examine how these problems are formally diagnosed and categorized in this population. How alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are categorized may have implications for secondary prevention or intervention research in persons with SCI. Without an easily measured physiological marker for severity of alcohol use, diagnostic criteria are the only gold standard for clinical diagnosis. Criteria have been evolving through iterations of different diagnostic classification systems. But, iterations of diagnostic classification systems may result in different diagnoses in patient populations. The purpose of this manuscript was to help lend guidance to whether the new diagnostic classification scheme for alcohol use is appropriate for individuals who have suffered a SCI.

The goal of this investigation was to examine whether AUDs are more accurately conceptualized categorically as abuse and dependence as in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV9) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition -Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR10) or on a single continuum with mild to severe category ratings as in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-511). According to both the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR, alcohol abuse was defined as a maladaptive pattern of chronic alcohol use accompanied by psychosocial consequences, whereas alcohol dependence was defined as the combination of cognitive, behavioral and physiological symptoms resulting from alcohol use despite the experience of adverse consequences.9, 10 Alcohol dependence requires the experience of tolerance, withdrawal and/or compulsive drug use. Compulsive drug use includes behaviors such as increased consumption of alcohol in larger quantities over time, unsuccessful quit attempts, spending a great deal of time obtaining alcohol, using it, or recovering from its effects, and/or continued use despite social, occupational, physical or psychological consequences. The current diagnostic classification system, DSM-5, integrates the two DSM-IV disorders, alcohol abuse and dependence, into a single disorder called AUD with mild, moderate and severe sub-classifications (Table 1).

Research using population-based and clinical samples of adults and adolescents has provided mixed support for the dichotomous categorical structure of DSM-IV AUDs (for example, see refs 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). Test–retest reliabilities have been found to be moderate to high for alcohol dependence, but lower for alcohol abuse (for example, see refs 17, 18). Factor analytic studies of AUDs have produced inconsistent findings. Some studies indicate better fit for a two-factor model, supporting the DSM-IV diagnostic structure (for example, see refs 19, 20). In other studies, a dominant single factor emerges that is consistent with the DSM-511 diagnostic classification (for example, see refs 15, 16, 21). Overall, findings from test–retest and factor analytic studies provide inconclusive evidence with respect to the structure of DSM-IV AUD criteria.

In response to evidence that the DSM-IV AUD criteria do not represent distinct diagnostic categories entities (for example, see refs 15, 16, 21), the current edition of the DSM, DSM-5,11 has combined alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence into one diagnostic entity, AUD, with associated severity indicators (Table 1). Despite the fact that ~48% of persons at least 1 year following SCI engage in moderate to heavy drinking,23 and ~14% of persons 10 years following SCI screen positive for alcohol abuse,8 no research has examined the proposed factor structure of AUD criteria using a sample of individuals with SCI.

Previous studies have examined the factor structure of DSM-IV AUD criteria in other clinical samples (for example, see ref. 21), but none have examined the dimensionality of these criteria using Rasch analysis in individuals with SCI. The goal of this study was to examine the dimensionality and other psychometric characteristics of DSM-IV AUD symptoms in a sample of individuals with SCI. We hypothesized that the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) will be unidimensional in our sample of individuals with SCI, reflecting a single latent construct or factor consistent with the DSM-511 diagnostic model.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data for this study were drawn from a multi-center (that is, University of Michigan, University of Washington, Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan and Santa Clara Valley Medical Center) investigation of risk factors associated with post-injury depression. Informed consent procedures were completed according to institutional review board guidelines. Participants completed an in-depth, structured interview that involved the assessment of early childhood exposure to adversity, stressful life events, social support, current depressive symptoms and injury-related factors. Participants also completed a telephone interview lasting 30–40 min. Data used in this current analysis were demographic and injury-related characteristics (that is, cause of injury, date of injury, injury level and severity), as well as the alcohol abuse and dependence modules of the SCID-I/NP22. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Participants

Data from 379 individuals who sustained SCI either traumatically or non-traumatically after the age of 18 and were at least 1 year post injury were used for this investigation. There were no exclusions based on level, severity or etiology of SCI, with the exception of individuals who incurred their SCI because of terminal disease or other chronic disease with gradual onset of impairment.

Measures

Demographic and injury characteristics

Participants provided demographic information including gender, age, racial background, time since injury, type and cause of injury (for example, paraplegic, tetraplegic, complete vs incomplete) and highest education level via telephone interview or medical record review.

Alcohol use

AUD symptoms were assessed using the SCID-I/NP;22 a semi-structured clinical interview designed to be administered by mental health professionals was completed via telephone. The SCID-I/NP22 includes modules specifically dedicated to assess alcohol abuse and dependence according to the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria (Table 1). Only participants who meet screening criterion for the lifetime assessment of AUDs according to the SCID-I/P NP completed alcohol abuse and dependence modules. Screening criterion was a question assessing lifetime use of five or more drinks in one occasion. If participants responded yes, they completed the lifetime assessment of alcohol use module. Training for the SCID was coordinated between centers to ensure that research assistants administered the instrument in a standardized fashion.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for the sample and endorsement of the SCID-I/NP alcohol abuse and dependence criteria were examined to assess prevalence statistics in this sample. The Rasch rating scale model was used to evaluate dimensionality of the SCID-I/NP alcohol abuse and dependence criteria. The Rasch rating scale model rather than the partial credit model was used because the SCID-I/NP alcohol abuse and dependence items all share the same rating scale structure. Rasch analysis is a probabilistic mathematical model that estimates item difficulty, person ability and threshold for each response category on a single continuum logit scale (log-odds units). Rasch analysis was conducted using Winsteps 3.80.1 software.24 To evaluate the SCID-I/NP items, unidimensionality, reliability and targeting were examined.

Unidimensionality indicates that a score produced by a measure represents a single concept. To assess unidimensionality, infit and outfit mean squares statistics were examined.25, 26 Infit means inlier-sensitive, whereas outfit means outlier-sensitive fit. Infit and outfit mean-square ranges of 0.6–1.4 are considered reasonable for rating scales.26, 27, 28 Unidimensionality was also assessed using a principle component analysis of Rasch residuals, where residuals can be understood as the difference between observed and expected values. Rasch rating scale structure parameters were examined via Andrich thresholds.

Internal consistency of person and item performance on the SCID-I/NP was evaluated by examining separation reliability estimates and separation ratios.26 Separation reliability for persons refers to the consistency of person response across items, whereas the separation reliability for items refers to the consistency of item performances across persons. Similar to Cronbach alpha, separation reliability estimates the ratio of the true score variance to the observed score variance, and its value ranges from 0 to 1. To overcome the potential for ceiling effect in separation reliability, each separation reliability estimate has a corresponding separation ratio (theoretical value ranging from 0 to infinity), which is the ratio of the true adjusted s.d. of measures to the average s.e. of measures. Separation ratios >2 provide evidence of internal consistency.27

Targeting of item endorsability was assessed by comparison of the distribution and spread of items and persons along a common logit scale of the latent construct (for example, examination of the item-person map28). Item targeting is represented by a person–item map that provides visual observation of the relative position of item difficulty to a person's ability. Targeting refers to how well item difficulty matches the participant's ability. Similar to the Rasch model for dichotomous items, the Rasch rating scale model reports both item difficulties and person abilities, and it also provides a single set of thresholds for the rating scale that is common to all the items. These thresholds represent the point or boundary at which the likelihood of being observed in a given response category is exceeded by the likelihood of being observed in the next higher category.28 For a well-targeted instrument, mean item difficulty is usually set at zero; the greater the difference of item and participant parameters, the poorer the targeting.

Results

Sixty-six percent of this sample were male. Seventy-seven percent were Caucasian, 13% were African American, 4% were Hispanic and 2% were Asian. Thirty-four percent earned a college degree, 30% completed some college, 16% earned a graduate degree and 16% earned a high school diploma. The average age was 49 years (s.d.=13.3 years), and the average age at injury was ~34 years (s.d.=14.4 years). The average time since injury was 15 years (s.d.=11.2 years). Fifty-two percent (n=190) of this sample was diagnosed with paraplegia (48% diagnosed with tetraplegia), and approximately half of the entire sample (51%; n=184) had incomplete injuries. Fifty percent of the entire sample (n=183) were injured by vehicular collision, 21% were injured by falling, 11% were injured by violence and 9% were injured by playing sports. Fifty-seven percent (n=166) of the entire sample endorsed criteria for alcohol abuse, and 25% (n=65) endorsed criteria for alcohol dependence.

Overall, fit values were generally acceptable except for one item (that is, alcohol abuse criterion 2), suggesting that the items fit the expectation of unidimensionality (Table 2). Infit mean-square values ranged from 0.76 to 1.30, which is considered to be ‘very good.’ Outfit mean-square values ranged from 0.52 to 2.44. Alcohol abuse criterion 2’s outfit mean-square was 2.44, which suggested item misfit (Table 2). The outfit mean-square values of the remaining items ranged from 0.52 to 1.07. Given that infit and outfit mean-square statistics for alcohol abuse and dependence items were generally acceptable, these results support that the items represent a unidimensional construct.

Examination of the principal components analysis, however, did not provide support for unidimensionality. Variance explained by the scale was only 42.9%. Modeled variance, or the variance that would be explained if the data exactly fit the Rasch model, was 43.4%.

The person separation ratio was 0.99, with a corresponding person reliability of 0.49. The item separation ratio was 6.19, with a corresponding item reliability of 0.97. The item–person map is shown in Figure 1. An item–person map with good targeting would be symmetric along the vertical axis with items and persons clustered in a similar fashion with a similar range. These was not the case for the SCID-I/NP alcohol abuse and dependence items, where item measures ranged from −1.42 to 0.93 logits, whereas person measures ranged from −2.93 to 2.80. As noted earlier, the item–person map illustrates this poor targeting of items. Notably, items on the right side of the map measure a narrower range of the construct of alcohol disorder than would be necessary to adequately characterize the participants.

Discussion

Results of Rasch analyses indicated that the data fit a unidimensional model, which provides evidence that previously dichotomized alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms reside on a continuum for persons with SCI. Results of the principle components analysis did not provide support for unidimensionality. This pattern of findings may be due to the following:22 the SCID-I/NP is short with only 11 items,1 the item–person map (Figure 1) reveals poor targeting, and2 there was a floor effect with 20% of the sample obtaining the minimum score. Notably, item–person maps do not directly assess dimensionality, item–person maps address whether the scale assesses the full ‘range’ of the construct (that is, having enough items covering easy endorsibility to infrequent endorsibility). Another problematic aspect of this scale is its middle rating category, ‘sub-threshold.’ It was infrequently endorsed by participants in our sample, which led to disordered Rasch–Andrich thresholds. In addition, results revealed a low person reliability, which also suggests that the SCID-I/NP needs many more items.

Without an easily measured biological marker for severity of alcohol use, its diagnostic criteria are the only gold standard for clinical diagnosis. Criteria have been evolving through iterations of different diagnostic classification systems. This study examined the dimensionality of DSM-IV-Text Revision10 alcohol abuse and dependence criteria in persons with SCI using data from the alcohol use and abuse modules of the SCID-I/NP.22 In light of the recently published DSM-5,11 which integrates the two DSM-IV-Text Revision alcohol-related disorders, alcohol abuse and dependence, into a single disorder called an AUD, as well as the controversy surrounding the factor structure of alcohol abuse and dependence criteria (for example, see refs 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21), this investigation is timely. Overall, the findings from this evaluation lend support for the current diagnostic structure in the DSM-5.11 As noted by Saha et al.,16 the development of measures of AUDs residing on a continuum holds promise for research in the neurobiology and genetics of AUDs given that previous categorical diagnostic phenotypes have posed considerable challenges to those fields.29, 30

Given the high rate of alcohol abuse and dependence among persons with SCI found in this investigation as well as in previous studies,8, 23 accurately assessing alcohol use following SCI is important. Given the paucity of literature on this subject matter, no studies have been conducted to examine that different conceptualizations of problematic alcohol use affect rate of diagnosis. Thus, this is an important target for future research. The consequences of poor identification of alcohol use conditions can negatively impact treatment and subsequently the health of persons with SCI. Crutcher et al.31 found that intoxication in persons with SCI at the time of admission to the hospital was associated with extended length of stay in the hospital, more days spent ventilated, and increased risk for complications including pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Alcohol abuse following SCI has been cited as an obstacle to rehabilitation and correlated with longer hospital lengths of stays, poorer rehabilitation outcomes, decreased life satisfaction, depression, anger, anxiety, as well as poorer ratings of health and impaired self-care.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Problematic alcohol use is likely to negatively affect rehabilitation outcomes such as community integration, return to work, as well as basic/instrumental activities and self-care. Thus, assessment of appropriate diagnostic criteria will guide the rehabilitation specialist to the appropriate intervention and awareness of potential barriers to maximizing rehabilitation.

Conclusion

In summary, the SCID-I/NP alcohol abuse and dependence items appear to be a reasonably unidimensional scale, which reflects a single latent construct or factor consistent with the DSM-511 diagnostic model. One important caveat is that the SCID-I/NP22 appears to have too few items to adequately assess the latent construct of alcohol abuse or dependence. Additional limitations of this investigation include floor effects, poor item–person map targeting and disordered Rasch–Andrich thresholds. Moreover, the ‘sub-threshold’ rating category adds ‘noise’ to the instrument; binary rating of the items (that is, symptom present/absent) should be considered in future revisions of the scale. Thus, the results of this investigation are important but should be replicated in the absence of the aforementioned limitations. To our knowledge, this study includes the largest sample of completed SCID-I/NPs in people with SCI from diverse geographic backgrounds, which are important strengths of this investigation.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

World Health Organization. Spinal Cord Injury. 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs384/en/#. Accessed on May 2015.

Bombardier CH, Stroud MW, Esselman PC, Rimmele CT . Do preinjury alcohol problems predict poorer rehabilitation progress in persons with spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1488–1492.

Bombardier CH, Temkin NR, Machamer J, Dikmen SS . The natural history of drinking and alcohol-related problems after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 185–191.

Heinemann AW, Doll MD, Kevin JA, Schnoll S, Yarkony G . Substance use and receipt of treatment by persons with long-term spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 72: 482–487.

Richards JS, Kewman DG, Pierce CA . In: Frank RG, Elliott TR (eds). Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. American Psychological Association: Washington, USA. 2000, pp 11–26.

Stroud MW, Bombardier CH, Dyer JR, Rimmele CT, Esselman PC . Preinjury alcohol and drug use among persons with spinal cord injury: implications for rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 461–472.

Tate DG . Alcohol use among spinal cord injured patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 72: 192–195.

Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Krause JS, Meade MA, Bombardier CH . Patterns of alcohol and substance use and abuse in persons with spinal cord injury risk factors and correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1837–1847.

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, USA. 1994.

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, USA. 2000.

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, TX, USA. 2013.

Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Reich T, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, Nurnberger JI Jr et al. Can we subtype alcoholism? A latent class analysis of data from relatives of alcoholics in a multicenter family study of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; 20: 1462–1471.

Kahler CW, Strong DR . A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006; 30: 1165–1175.

Lynskey MT, Nelson EC, Neuman RJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PF, Knopik VS et al. Limitations of DSM-IV operationalizations of alcohol abuse and dependence in a sample of Australian twins. Twin Res Hum Gen 2005; 8: 574–558.

Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW . Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannibis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol 2006; 115: 807–814.

Saha TD, Chou PS, Grant BF . Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 931–941.

Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E . Substance use disorders: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and international classification of diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10). Addiction 2006; 101 (Suppl. 1): 59–75.

Horton J, Compton W, Cottler LB . Reliability of substance user diagnoses among African-Americans and Caucasians. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 57: 203–209.

Harford TC, Muthen BO . The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: a multivariate analysis of DSM-IV symptom items in the national longitudinal survey of youth. J Stud Alcohol 2000; 62: 150–157.

Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthen BO, Yi H, Hasin DS, Stinson FS . DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 86: 154–166.

Ray LA, Kahler CW, Young D, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M . The factor structure and severity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in psychiatric outpatients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2008; 69: 496–499.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW . Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, USA. 2002.

Saunders LL, Krause JS . Psychological factors affecting alcohol use after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 637–642.

Linacre JM . Winsteps Rasch Measurement Computer Program. Beaverton, OR, USA. 2016.

Gustafsson JE . Testing and obtaining fit data to the Rasch model. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1980; 33: 205–233.

Wright BD, Linacre JM . Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions 1994; 8: 370.

Linacre JM . Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J Appl Meas 2002; 3: 86–106.

Bond TG, Fox CM . Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Erlbaum: London, UK. 2001.

Gottesman II, Gould TD . The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 636–645.

Hines L, Ray LA, Hutchinson KE, Tabakoff B . Alcoholism: the dissection for endophenotypes. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2005; 7: 153–163.

Crutcher CL, Ugiliweneza B, Hodes JE, Kong M, Boakye M . Alcohol intoxication and its effects on traumatic spinal cord injury outcomes. J Neurotrauma 2014; 31: 798–802.

Hawkins DA, Heinemann AW . Substance abuse and medical complications following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 1998; 43: 219–231.

Heinemann AW, Hawkins DA . Substance abuse and medical complications following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 1995; 40: 125–140.

Krause JS, Coker J, Charlifue S, Whiteneck GG . Health behaviors among American Indians with spinal cord injury: comparison with data from 1996 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1435–1440.

McKinley WO, Kolakowsky SA, Kreutzer JS . Substance abuse violence and outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 78: 306–312.

Tate DG . The use of the CAGE questionnaire to assess alcohol abuse among spinal cord injury persons. J Rehabil 1994; 60: 31–35.

Bombardier CH, Rimmele C . Alcohol use and readiness to change after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1110–1115.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this paper were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number H133G070020). NIDILRR is a center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS and one should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reslan, S., Kalpakjian, C., Hanks, R. et al. Rasch analysis of alcohol abuse and dependence diagnostic criteria in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 55, 497–501 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.146

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.146