Abstract

Study design:

A process evaluation of a clinical trial.

Objectives:

To describe the roles fulfilled by peer health coaches (PHCs) with spinal cord injury (SCI) during a randomized controlled trial research study called ‘My Care My Call’, a novel telephone-based, peer-led self-management intervention for adults with chronic SCI 1+ years after injury.

Setting:

Connecticut and Greater Boston Area, MA, USA.

Methods:

Directed content analysis was used to qualitatively examine information from 504 tele-coaching calls, conducted with 42 participants with SCI, by two trained SCI PHCs. Self-management was the focus of each 6-month PHC–peer relationship. PHCs documented how and when they used the communication tools (CTs) and information delivery strategies (IDSs) they developed for the intervention. Interaction data were coded and analyzed to determine PHC roles in relation to CT and IDS utilization and application.

Results:

PHCs performed three principal roles: Role Model, Supporter, and Advisor. Role Model interactions included CTs and IDSs that allowed PHCs to share personal experiences of managing and living with an SCI, including sharing their opinions and advice when appropriate. As Supporters, PHCs used CTs and IDSs to build credible relationships based on dependability and reassuring encouragement. PHCs fulfilled the unique role of Advisor using CTs and IDSs to teach and strategize with peers about SCI self-management.

Conclusion:

The SCI PHC performs a powerful, flexible role in promoting SCI self-management among peers. Analysis of PHC roles can inform the design of peer-led interventions and highlights the importance for the provision of peer mentor training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a complex condition that requires significant adjustment for the individual, their family and community.1, 2 Those living with SCI are at risk of developing conditions that impact physical and psychosocial health,2, 3, 4, 5 many of which can be successfully managed with appropriate resources and services.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Unfortunately, individuals with SCI struggle with adjustment because they often lack access to these resources and do not have the skills to effectively manage their long-term health.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Self-management emphasizes a person-centered role in chronic health management and focuses on medical management, maintaining life roles, managing negative emotions, such as fear and depression, and providing individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills and confidence to deal with health-related problems.16, 17 Finally, self-management prepares individuals to collaborate with health-care professionals and effectively navigate the health-care system.16, 17 Successful self-management is linked to health-care empowerment: being engaged, informed, collaborative, committed, and tolerant of uncertainty regarding health care.18 It emerges from a combination of an individual’s self-efficacy and support through social networks and social services.18, 19, 20, 21

Peer support has shown promise in encouraging self-management and increasing health information knowledge for adults during the first year post-SCI.5, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 SCI peer mentors have a lived experience with SCI, including acute hospitalization, rehabilitation and successful community re-integration.1 They provide understanding and support to help another adjust to living with and managing an SCI.1, 25, 27, 28 Most existing models of SCI peer mentoring involve face-to-face meetings between peers and peer mentors who are carefully matched based on demographics, such as age, race, etiology, severity of injury and geographic location.1, 24, 25, 29 The influence of peer support during the first year post-SCI has been shown to have a positive influence on adjustment and self-efficacy.1, 25, 27 Specific components that distinguish the peer mentor relationship from other supportive relationships include credibility, equitability, mutuality, acceptance and normalization.1 Community-based peer support is valuable to both individuals with SCI and the multidisciplinary health-care team and results in positive self-management outcomes.2, 30 Little remains known about how SCI peer mentors interact with community-dwelling peers beyond the first year post-injury.2, 22, 23, 31

Results of an SCI self-management intervention called ‘My Care My Call’ (MCMC) show promising impact of a trained SCI peer health coach (PHC). MCMC reported statistically significant improvements in: health self-management skills and behavior, experiences with primary care engagement, health-related quality of life, and social medical support for those who received self-management coaching from a PHC via telephone for 6 months compared with those who did not.30 PHCs are people with chronic conditions who are trained to provide self-management education and support to others with the same chronic condition.32, 33

The results of MCMC warrant secondary analysis to advance the understanding of the SCI PHC. Identifying the fundamental functions of an SCI PHC informs the design of peer-led interventions for those with SCI, is beneficial for organizations that provide peer mentor training and provides an argument to incorporate SCI PHCs into the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. This paper uses the qualitative methodology of directed content analysis34, 35 to explore PHC roles in MCMC. The major aims include: (1) describing the communication tools and information delivery strategies used by PHCs; (2) describing PHC roles and identifying the components of each role in relation to the interplay of communication tools and information delivery strategies; (3) examining patterns of PHC roles during the 6-month PHC–peer relationship.

Methods

Design

The MCMC study is described in detail elsewhere.21, 30 This RCT enrolled 42 individuals in the intervention group compared with 42 control individuals who received usual care. Eligibility criteria included: age ⩾18 years, chronic traumatic SCI (⩾1 year postinjury), endorsement of an unmet primary prevention or self-management need, and telephone access. The intervention consisted of 8 weekly calls, 4 bi-weekly calls and 2 monthly calls, for a total of 14 calls over the course of 6 months. Calls focused on self-management and unmet health-care needs, peers chose conversation topics and PHCs had the flexibility to use specific tools and strategies to facilitate and focus conversations. PHCs and peers mutually agreed to extend weekly or bi-weekly calls based on individual circumstances.

Two experienced peer mentors with SCI 5+ years post injury were trained as PHCs to tele-coach peer participants (peers) on self-management of health and health-care needs. Both PHCs were part-time paid employees and members of the MCMC research team. PHCs received training in: peer mentoring from an SCI association, SCI-related resources, effectively using their story to coach peers, essential motivational interviewing (MI) skills, and certification in Brief Action Planning (BAP).36 BAP is a highly structured goal-setting tool that follows the health empowerment approach and uses a detailed conversation script to support self-management behaviors through setting goals that are specific, measureable, achievable, relevant and timed.34, 35, 36 PHCs completed 15 h of in-person and 40 h of telephone-based training over 12 weeks.

During the intervention, PHCs conducted calls with peers utilizing a ‘toolkit’ comprised of seven communication tools (CTs), and five information delivery strategies (IDSs). CTs are semiscripted conversation guides, including: Shared Story (SS), a method of communicating specific personal experiences; Identifying Support Systems, a method of assisting a peer with identifying supports and support services; BAP; Resource Review (RR) for education and resource referral; Affirmation Statements for support; In-between Call Text Encouragement and Reminders; and Reflective Listening (RL) and related essential MI skills. RL is the most active form of listening, with the peer sharing his/her experience and the PHC reflecting this back to the peer in a non-judgmental way. For example, the Resource Review CT directs the PHC to use RL by asking a peer to share what they learned after reviewing a specific piece of information (that is, a health-related factsheet). The PHC then reinforces learning by restating and affirming what the peer shared. CTs are described in detail in Table 1.

IDSs are approaches PHCs utilized to focus a call, choose CTs and/or deliver, enhance and simplify information exchange (Table 1). Relationship Building was used to cultivate a rapport based on trust, credibility and mutual respect; Sharing of Opinion was used to share perspective with a peer about the topic discussed (used with peer-granted permission); Sharing of Advice was used to provide specific ideas and information the PHC believed helpful for a peer regarding the topic discussed (used with peer-granted permission); Action Planning addressed an issue through problem-solving and decision-making; and sending Postcall Support Package texts and/or emails were strategies PHCs used to encourage peer education and resource awareness.

Data

Data for this qualitative analysis includes the CTs and IDSs used by PHCs and how they were incorporated during interactions. PHCs documented CT and IDS utilization on a secured, online tracking site. ‘Check box’ responses linked to open-ended ‘text box’ responses allowed PHCs to connect relevant contextual information CT and IDS use. Additionally, peers and PHCs completed postintervention telephone interviews regarding their satisfaction with, and experiences during, the intervention. Interviews were transcribed from audio recordings and relevant quotes were incorporated into the analysis. Five hundred and four calls were conducted over 6 months.

Analysis

A directed content analysis approach was utilized to organize and examine data34, 35 in order to validate and conceptually expand on previous research reported about diabetes self-management peer coaches.37 Data were co-analyzed by the first author who was a PHC and the second author who assisted with PHC training and met weekly with both PHCs via phone meetings during the intervention phase.

At study completion, analysts developed operational definitions for each CT and IDS. Content was then coded into reported roles fulfilled by diabetes self-management peer coaches: Role Model, Supporter, and Advisor, and subcoded into six subcategories also identified by Goldman et al.37 Quotes from poststudy participation interviews with peers and PHCs were also coded to increase understanding of peer and PHC perceptions of PHC roles.

Researchers compared coded categories and subcategories to determine consistency, frequency and context of CT and IDS utilization. Additionally, the NVivo version 11.3 software was used to understand the combinations of tools and strategies used in each role. Inter-relations were conceptually mapped to develop models for PHC roles. Finally, data were analyzed in three 2-month time periods to explore PHC roles throughout the 6-month intervention.

Each investigator independently coded data and then compared coding. Disagreement was found in very few cases, and consensus was easily reached as rationales for coding were further discussed. In this analysis, the validity of responses as representative of the overall PHC role framework was determined by reaching a state of saturation (when very little new information was gleaned from additional coding). Saturation was reached after 20 data points were subcoded and supportive quotes were categorized. Analysis was structured so that only aspects that fit the matrix were chosen.

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research and that authors were given institutional approval to conduct this qualitative analysis.

Results

Aim 1: tool and strategy use

Table 2 illustrates the results of CT and IDS analysis, and Table 3 describes the frequencies of CT and IDS utilization with examples from the analysis.

RL was the most frequently used CT, and three CTs served multiple functions. PHCs incorporated RL and SS in Role Model, Supporter and Advisor interactions. PHCs used Identifying Supports in the role of Supporter by assisting peers in identifying personal supports (friends and family) and in the role of Advisor by assisting peers in identifying providers (physicians, therapists, personal care attendants, rehabilitation facilities/clinics and durable medical equipment vendors). Similarly, PHCs used text messaging to both support and advise.

Postcall Support Package was the most frequently used IDS. PHCs reported specific IDSs for each role: opinion and advice sharing while acting as Role Model, providing affirmations and support when working as Supporter, and goal setting and sending Postcall Support Packages when working as Advisor.

Aim 2: SCI PHC role and components

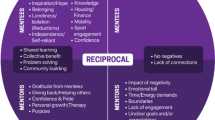

PHCs reported utilizing CTs and IDSs in specific and consistent combinations to perform as Role Model, Supporter and Advisor. Exploring this interplay provides an in-depth understanding of PHC roles. Figure 1 presents a visual representation of each role in relation to its components. Table 4 describes the frequency of call topics.

PHC as role model

During Role Model interactions, PHCs used RL to empathize and bond with peers over common encounters and struggles, such as medication use as a necessity, regardless of side effects. SS was used to disclose personal experiences and lessons learned regarding successfully managing their SCI.38 PHCs used the IDSs of opinion and advice sharing related to exemplifying self-management, for example, directing wheelchair maintenance. PHCs also modeled health-care communication and navigation skills.

Peer-identified Role Model interactions postintervention:

‘I learned that there were a lot of people out there that go through the same things that I went through and are able to do fine in life after having something like that happens’.

‘[What was most helpful was my PHC] listening to my problems and giving me advice on it.’

A PHC was able to describe using Role Model CTs postintervention:

‘…using your story, along with this really powerful tool…reflective listening, combining those two things—how to stay with someone, be with someone, let them know you’ve heard them and then relate experiences you have had and how, what you did, but not in a judgmental way’.

PHCs related to peers using their personal experiences of managing an SCI, including sharing their opinions and advice when appropriate.

PHC as supporter

The Supporter role incorporated RL, SS, In-between Call Support, Identifying Supports, Providing Affirmations and the IDS Relationship Building.38 PHCs used RL and SS to build trust with peers and focus calls on building confidence in self-management skills. Affirmations guided peers in strengthening personal support systems by identifying supportive friends and family members. Additionally, text messaging was used to provide In-between Call Support. PHCs reported the need to build a relationship so they could encourage and motivate.

Peers expressed Supporter role interactions postintervention:

‘[It’s] good for people to know there’s someone willing to stand by them, even if it’s only through phone contact, someone who actually is consistent’.

‘[My PHC] was a good cheerleader, a person who would support you regardless of how you were able to accomplish what they suggested. [The PHC] was a very positive, re-enforcer to whatever you achieved’.

A PHC described the Supporter role postintervention:

‘Consistency of ‘every week I’m going to call you’….a lot of people who don’t have a lot of support don’t trust other people for good reason, because people don’t stick around for them. Having to prove yourself is pretty important. I’m not going to make you share your life with me and then just leave’.

As Supporters, PHCs used specific CTs to build supportive relationships based on reliability and reassuring encouragement.

PHC as advisor

RL, SS, Identifying Supports, BAP, Resource Review and In-Between Call Text Reminders were the CTs reported to encompass the Advisor role.38 IDSs included sending tailored Postcall Support Packages and Action Planning. The Advisor role involved teaching and strategizing interactions. PHCs taught by combining RL and Resource Review to share pertinent information with peers regarding health and SCI, assistive technology and navigating the health-care system. As teachers, PHCs sent Postcall Support Packages to reinforce peer learning. When strategizing, PHCs used RL, SS, Identifying Supports and BAP (Figure 2) to facilitate self-management skill development and behavior change. Additionally, PHCs provided peer-requested text messages in between calls, reminding peers of their goals and action plans. Action Planning was the identified IDS during strategizing calls.

Peers recognized Advisor role interactions:

‘[The MCMC program] kept me accountable to myself, helped me set goals, and kept me apprised of those goals, kept reminding me of what they were and that I needed to work toward them’.

‘It was easier to do the things you needed to do, and having someone to talk to about it every week and that holds you accountable’.

PHCs identified acting as Advisor:

‘BAP [is] a great process and I really saw some awesome results. It made a big impact’.

‘You use your story to just be there with someone, which is being a peer. Saying ‘I have experience with that, do you want to know what I did?’ and they say ‘yeah I do’ and you tell them…that’s when you’re a coach’.

Accountability and the ability to strategize are important aspects of the Advisor role.

Aim 3: PHC role patterns

Figure 3 describes PHC roles in relation to each 2-month timeframe of the intervention. Months 1–2 involved weekly calls, and PHCs reported the majority of their interactions with peers as Supporter, followed by Advisor, then Role Model. Months 3–4 consisted of bi-weekly calls, and 11 (26%) peers chose to continue with weekly call. During this timeframe, PHCs interacted mostly as Supporter followed by Role Model and Advisor. Months 5–6 consisted of monthly calls, with 17 (40%) peers continuing with a bi-weekly calls schedule. PHCs reported the most interactions as Supporter and Advisor during the final 2 months.

Discussion

Utilizing an SCI PHC to address self-management with peers is an expanded application of SCI peer mentoring. Targeted training in MI skills allowed PHCs to interact with peers in a judgment-free space and cultivate relationships based on understanding and trust. Training allowed PHCs to develop proficiency in using a variety of CTs and IDSs to provide peers with empathy, modeling, encouragement, educational information and assistance with developing problem-solving and goal-setting skills.

Analysis confirmed PHCs fulfilled three principal roles during MCMC: Role Model, Supporter, and Advisor.38 Role Model was foundational in that PHCs used shared, real-life experiences to relate to peers and therefore become a credible resource.2 Supporter was more complex because PHCs utilized additional CTs and interactions to emotionally connect, support and build trust with peers.

Supporter and Role Model are typical roles in SCI peer mentoring.1, 25, 27 That of trained Advisor is unique. As Advisor, PHCs worked as teacher and strategist by utilizing CTs and IDSs to support peers with acquiring knowledge, building competence in self-management skills and embracing positive behavior change.37, 39

Analysis revealed that PHCs utilized CTs and IDSs to listen attentively, ask questions relevant to the needs of peers and assist peers with addressing self-management in between coaching calls (Figure 1). PHC roles provided flexibility, a key characteristic in effective peer-based programming.2 The flexibility of using one CT in different ways allowed PHCs to remain peer-focused and adjust the conversation to meet a peer in a comfortable space to support learning. Flexibility to extend calls to weekly or bi-weekly gave peers the choice to continue working with a PHC more extensively.

When people are able to tell their story and feel listened to, they become a part of the process and, therefore, a willing co-problem solver.39, 40 This process is based on self-determination theory and embraced in the MI approach.41 It seeks to activate individuals by making them a part of the decision-making process, supporting self-reflection and engaging in problem-solving.42 Moreover, a person will take a more active role in enhancing their well-being once they recognize their social supports and social service resources.39

PHC role utilization and activation

An individual’s ability and willingness to take on the role of managing their health and health care is referred to as activation.43 Those who are more activated are more likely to display self-management and health information-seeking behaviors.18, 21, 37, 43 PHCs utilized their perception of a peer’s level of activation to tailor coaching calls38 by selecting CTs and appropriate information to share with peers. These are important foundations for tackling further self-management skills.43 PHCs worked with peers on handling new or challenging situations as they appeared. Not everyone is ready to address self-management, and when a peer was overwhelmed and unprepared to take action, the PHC met them in this space as Role Model and/or Supporter. PHCs worked as Advisor only when peers were ready to take action, and interactions focused on the adoption of a new health behavior (for example, deciding to quit smoking) and/or the development of problem-solving skills (for example, contacting a research study for free smoking patches).

PHCs fulfilled all three roles in varied proportions during intervention timeframes. The Supporter role was utilized the most in all three timeframes, illustrating that peers needed continued support to build a sense of self-efficacy.42, 44, 45 Role Model interactions were reported highest during the first 2 months, showing that the ability to relate is foundational to an effective PHC–peer relationship.1, 2 CT use was highest during the first 2 months, meaning PHCs used their training to ensure that calls were meaningful. Peers identified the ability to relate, credibility and reliability as important PHC characteristics that facilitated transition into Advisory role functions.

The Advisor role was relatively consistent throughout the intervention as PHCs worked with peers on a variety of self-management issues from understanding and addressing pain, spasticity and bladder management to fixing broken wheelchairs and encouraging effective communication with doctors and other health-care professionals. Peers needed an advisor to improve competence, and PHCs addressed this need.

It is widely accepted that an SCI peer mentor is a significant source of social support.29, 30, 32, 33 Yet the consistency with which PHCs acted as Advisor suggests that this role is meaningful in supporting self-management and improving activation.30 Our analysis demonstrates that a PHC can work with a peer through modeling, supporting and promoting self-management skills through teaching and strategizing. Trained SCI PHCs are powerful self-management resources for people living with SCI.

Limitations

The small size of the intervention group (n=42) in a small geographic area may have limited generalizability and was limited to working with people who could communicate by telephone, text and email. Peer participants needed to endorse an unmet primary prevention or self-management need to meet eligibility criteria and so may have been more aware of or motivated to address an unmet need. Finally, not everyone who has been living with an SCI for at least 1 year can relate to or benefit from this intervention because they may not need it when it is presented or may need more intensive assistance than a PHC can provide.

Conclusion

Tele-coaching by a trained PHC is a viable way to address SCI self-management effectively. Peer mentor programs can expand their community-based focus by reaching out to those beyond the first year post-SCI and training peer mentors in essential MI skills, RL and Advisor role tools and strategies. Telephone, email and text-based communication should also be encouraged, and virtual communication should be considered. A multisite trial conducted across community- and rehabilitation-based settings would be useful in verifying the adaptability and impact of the PHC role. SCI PHCs as members of the SCI health-care team may be a cost-effective approach, and further research to understand this potential will be beneficial.1, 24 We hope the SCI community will be the ultimate beneficiaries of this research.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA, Yasui NY . Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 2006; 51: 289–298.

Divanoglou A, Georgiou M . Perceived effectiveness and mechanisms of community peer-based programmes for spinal cord injuries—a systematic review of qualitative findings. spinal Cord 2016; 55: 225–234.

NSCISC National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Complete Public Version of the 2015 Annual Statistical Report for the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, USA, 2015).

Gabbe BJ, Nunn A . Profile and costs of secondary conditions resulting in emergency department presentations and readmission to hospital following traumatic spinal cord injury. Injury 2016; 47: 1847–1855.

Cogan AM, Blanchard J, Garber SL, Vigen CL, Carlson M, Clark FA . Systematic review of behavioral and educational interventions to prevent pressure ulcers in adults with spinal cord injury. Clin. Rehab. 2016; 20: 871–80.

McColl MA, Aiken A, McColl A, Sakakibara B, Smith K . Primary care of people with spinal cord injury. Can Fam Physician 2012; 58: 1207–1216.

The Special Interest Group (SIG) on SCI Model System Innovation. Toward a Model System of Post-rehabilitative Health Care for Individuals with SCI [Internet]. Washington, DC: National Rehabilitation Hospital: National Capital Spinal Cord Injury Model System (NCSCIMS); 2010. Available from: http://www.msktc.org/lib/docs/scimodelsysteminnovationreport.pdf.

Harrington AL, Hirsch MA, Hammond FM, Norton HJ, Bockenek WL . Assessment of primary care services and perceived barriers to care in persons with disabilities. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 88: 852–863.

Iezzoni LI, Killeen MB, O’Day BL . Rural residents with disabilities confront substantial barriers to obtaining primary care. Health Serv Res 2006; 41: 1258–1275.

Kroll T, Beatty PW, Bingham S . Primary care satisfaction among adults with physical disabilities: the role of patient-provider communication. Manag Care Q 2003; 11: 11–19.

Veltman A, Stewart D, Tardif G, Branigan M . Healthcare for people with physical disabilities - access issues. Medscape, 2016 [cited 19 December 2016]. Available from http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408122.

Lawthers AG, Pransky GS, Peterson LE, Himmelstein JH . Rethinking quality in the context of persons with disability. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15: 287–299.

Emerich L, Parsons KC, Stein A . Competent care for persons with spinal cord injury and dysfunction in acute inpatient rehabilitation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012; 18: 149–166.

Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Gray DB, Stark S, Kisala P et al. Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: a qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: 578–588.

Kroll T, Jones GC, Kehn M, Neri MT . Barriers and strategies affecting the utilisation of primary preventive services for people with physical disabilities: a qualitative inquiry. Health Soc Care Community 2006; 14: 284–293.

Barlow JH, Wright CC, Turner AP, Bancroft GV . A 12-month follow-up study of self-management training for people with chronic disease: are changes maintained over time? Br J Health Psychol 2005; 10: 589–599.

Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M . Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract 2001; 4: 256–262.

Shearer N . Health empowerment theory as a guide for practice. Geriatr Nurs 2009; 30 (2 Suppl): 4–10.

Hibbard H, Greene J, Tusler M . Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient’s level of activation. Am J Manag Care 2009; 15: 353–360.

Gutnick D, Reims K, Davis C, Gainforth H, Jay M, Cole S . Brief action planning to facilitate behavior change and support patient self-management. Cited 20 December 2016. Available from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286176637_Brief_action_planning_to_facilitate_behavior_change_and_support_patient_self-management.

Houlihan BV, Everhart-Skeels S, Gutnick D, Pernigotti D, Zazula J, Brody M et al. Empowering adults with chronic spinal cord injury to prevent secondary conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016; 97: 1687–1695.e5.

Dorstyn D, Mathias J, Denson L . Applications of telecounselling in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: a systematic review with effect sizes. Clin Rehabil 2013; 27: 1072–1083.

Dorstyn D, Mathias J, Denson L, Robertson M . Effectiveness of telephone counseling in managing psychological outcomes after spinal cord injury: a preliminary study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 2100–2108.

Haas BM, Price L, Freeman JA . Qualitative evaluation of a community peer support service for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 295–299.

Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A, Gordon S . Using peer mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J Clin Nurs 2011; 20: 351–358.

Munce SE, Webster F, Fehlings MG, Straus SE, Jang E, Jaglal SB . Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 48.

Sherman JE, DeVinney DJ, Spearling KB . Social support and adjustment after spinal cord injury: influence of past peer-mentoring experiences and current live-in partner. Rehabil Psychol 2004; 49: 140–149.

Hernandez B, Hayes E, Balcazar FE, Keys CB . Responding to the needs of the underserved: a peer-mentor approach. SCI Psychosoc Process 2001; 14: 142–149.

Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation. Cited 10 February 2017. Available from https://www.christopherreeve.org/.

Houlihan B, Brody M, Everhart-Skeels S, Pernigotti D, Burnett S, Zazula J et al. Randomized trial of a peer-led, telephone-based empowerment intervention for persons with chronic spinal cord injury improves health self-management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017; 98: 1067–1076.

Haas BM, Price L, Freeman JA . Qualitative evaluation of a community peer support service for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 295–299.

Nettles A, Belton A . An overview of training curricula for diabetes peer educators. Fam Pract 2010; 27 (Suppl 1): i33–i39.

Sullivan ED, Joseph DH . Struggling with behavior changes: a special case for clients with diabetes. Diabetes Educ 1998; 24: 72–77.

Elo S, Kyngäs H . The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–115.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288.

The Centre for Collaboration, Motivation and Innovation (CCMI). Cited 2 December 2016. Available from http://www.centrecmi.ca/.

Goldman ML, Ghorob A, Eyre SL, Bodenheimer T . How do peer coaches improve diabetes care for low-income patients?: a qualitative analysis. Diabetes Educ 2013; 39: 800–810.

Everhart-Skeels S . How an SCI Peer Health Coach Influences Empowerment and Health Self-Management with Peers. American Spinal Injury Association: Albuquerque, NM, USA. 2017.

Wallerstein N, Bernstein E . Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q 1988; 15: 379–394.

Roter DL, Kinmonth A-L . What is the evidence that increasing participation of individuals in self-management improves the processes and outcomes of care? In: Williams R, Herman W, Kinmonth A-L, Wareham NJ (eds). The Evidence Base for Diabetes Care. John Wiley: New York, USA. 2002, pp 679–700.

Miller WR, Rollnick S . Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. Guilford: New York, USA. 2002.

Hibbard JH Using systematic measurement to target consumer activation strategies. Med Care Res Rev 2009; 66: 9S–27S.

Hibbard JH, Greene J . What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32: 207–214.

Bandura A . Self-efficacy mechanism in physiological activation and health-promoting behavior. In: Madden J, Matthysse S, Barchas J (eds). Adaption, Learning, and Affect. Raven Press: New York, USA. 1991, pp 226–269.

Battersby MW, Ask A, Reece M, Markwick MJ, Collins JP . The Partners in Health Scale: the development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management. Aust J Prim Health 2003; 9: 41–52.

Acknowledgements

Content was made possible with support from: The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Grant nos. H133N110019 and H133N120002 and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research Administration for Community Living Grant no. 90SI5013. We thank Pennie Huggins Cuevas, PhD, MD, for her ongoing interest in and support of this work; Damara Gutnick, MD, formerly of the Centre for Collaboration, Motivation and Innovation, for providing training and insight that helped guide the intervention at its inception; and Sam Burnett, MA, Co-director of the Centre for Collaboration, Motivation and Innovation, for ongoing support and open-mindedness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skeels, S., Pernigotti, D., Houlihan, B. et al. SCI peer health coach influence on self-management with peers: a qualitative analysis. Spinal Cord 55, 1016–1022 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.104

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.104

This article is cited by

-

Experiences of peer counselling during inpatient rehabilitation of patients with spinal cord injuries

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

A scoping review of peer-led interventions following spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

Process evaluations for large clinical trials involving complex interventions

Spinal Cord (2017)