Abstract

Study design:

The study uses a cross-sectional, group comparison, questionnaire-based design.

Objectives:

To determine whether spinal cord injury and pain have an impact on spiritual well-being and whether there is an association between spiritual well-being and measures of pain and psychological function.

Setting:

University teaching hospital in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Methods:

Questionnaires evaluating pain, psychological and spiritual well-being were administered to a group of people with a spinal cord injury (n=53) and a group without spinal cord injury (n=37). Spiritual well-being was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness and Therapy – Spirituality Extended Scale (FACIT-Sp-Ex). Pain and psychological function were also assessed using standard, validated measures of pain intensity, pain interference, mood and cognition.

Results:

Levels of spiritual well-being in people with a spinal cord injury were significantly lower when compared with people without a spinal cord injury. In addition, there was a moderate but significant negative correlation between spiritual well-being and pain intensity. There was also a strong and significant negative correlation between depression and spiritual well-being and a strong and significant positive correlation between spiritual well-being and both pain self-efficacy and satisfaction with life.

Conclusion:

Consequences of a spinal cord injury include increased levels of spiritual distress, which is associated, with higher levels of pain and depression and lower levels of pain self-efficacy and satisfaction with life. These findings indicate the importance of addressing spiritual well-being as an important component in the long-term rehabilitation of any person following spinal cord injury.

Sponsorship:

This study was supported by grant funding from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain following a spinal cord injury (SCI) can have a major impact on psychological function.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Although there is evidence to indicate that many people following a SCI adjust well over the long term,7 a substantial proportion of people have ongoing mood dysfunction.3, 4, 7 For those who have pain associated with their SCI, the added stress of persistent pain can place an additional burden that has a further impact on psychological function and quality of life.8, 9

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in existential or spiritual distress as an important component of suffering in response to disease or trauma. Although these issues have been well explored by those involved in end-of-life care,10, 11, 12, 13, 14 there is emerging evidence and support for their importance in the pain and rehabilitation settings.15, 16

The definition of spirituality sometimes causes confusion, and it is often assumed that it refers to a religious experience.17, 18 However, emerging consensus is that spirituality is a broader concept that for some people has no link to religion and incorporates more general issues of meaning, purpose and identity.14, 19, 20, 21, 22

It is often assumed that spirituality is more relevant to end-of-life care and has thus received greater attention because of specific issues related to death and dying. However, one study examining spiritual well-being in people with SCI demonstrated high levels of spiritual distress that significantly exceeded groups of people with cancer.15 Furthermore, in contrast to the people with cancer, spiritual distress was also a significant contributor to satisfaction with life in the rehabilitation group and more important than the physical disability associated with their injury.15

Although previous research15 has shown the importance of spiritual well-being in people with a SCI, the association with pain, a common additional cause of suffering in people with a SCI, has not been explored.23 Preliminary evidence within the cancer context suggests that the experience of pain is linked to higher levels of existential and spiritual distress.24 Therefore, the presence of pain in association with a SCI may place an additional burden.

Previous research in people with chronic pain indicates that higher levels of spiritual well-being are associated with an enhanced ability to cope with pain25, 26 and improved satisfaction with life.27 Thus, a better understanding of the impact of both SCI and pain on spiritual well-being and quality of life would assist in determining the importance of addressing spiritual well-being as part of a long-term rehabilitation approach.

The aims of this study, therefore, were to determine whether SCI was associated with high levels of spiritual distress and to examine the relationship between spiritual well-being and pain, as well as measures of physical and psychological function.

Materials and methods

Participants

People with SCI were recruited from a SCI participant database. The study included both men and women at least 18 years of age with complete and incomplete spinal cord lesions including those with paraplegia and tetraplegia.28 Participants were excluded if they had a diagnosed brain injury or were cognitively impaired. Control participants were individuals older than 18 years of age without SCI, brain injury or dementia who were able to understand and complete self-reporting psychological questionnaires. They were recruited through personal contact and unpaid advertisements in the local hospital setting. Ethics approval was obtained from the local institutional ethics committee, and all participants gave their own informed consent to participate in the study.

Outcome measures

All participants completed self-report measures relating to pain intensity, pain interference, psychological function and spiritual well-being. A pain numerical rating scale (NRS11, 0–10) was used to measure the average pain intensity over the previous week and high and low pain intensity scores. In order to assess the interference of SCI and associated pain on life, the pain interference subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory was used, a valid and widely used measure for assessing clinical pain.29 To reduce the potential bias associated with marked differences in locomotor function between groups, we changed item ‘c’ of the Brief Pain Inventory from ‘walking ability’ to ‘mobility’. This subscale scores 0 as no interference and 10 as complete interference. Participants’ mood was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), which uses a 4-point Likert-type scale and is well validated and widely used.30 Pain self-efficacy was measured using the pain self-efficacy questionnaire (PSEQ).31 Cognitive well-being was measured using the Satisfaction with Life (SWL) scale. The SWL scale is a reliable and valid tool that has also been shown to correlate with other measures of mental health and be predictive of future behaviours.32, 33

Spiritual well-being was assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Spiritual Well-Being-Extended questionnaire (FACIT-Sp-Ex). This is a widely used and validated scale that measures spiritual well-being as a component of quality of life in people diagnosed and treated for serious illness including people with cancer and HIV/AIDS.34 Responses are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0=not at all and 4=very much). There are subscales within the FACIT-Sp-Ex, with part A (items 1–12) measuring both meaning, peace and purpose in life (items 1-8) and faith (comfort and strength in one’s spiritual beliefs) (items 9–12), and part B (items 13–23) assessing relational aspects of spiritual well-being.35 Finally, we used the Spiritual Index of Well-Being (SIWB), another questionnaire designed to measure spirituality as a dimension of well-being36 in addition to the assessment of relationships between existential distress and satisfaction with life.37

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterise participants at study entry. To examine the impact of pain, group comparisons were made between those with no, minimal or mild pain (0–3 on pain intensity NRS) and those with moderate or severe pain (4–10 on pain intensity NRS). Groups (SCI with no or mild pain; SCI with moderate or severe pain; controls) were compared using the Mann–Whitney's U-test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Because of there being only three groups corrections to alpha levels were not considered necessary for the above post hoc tests.38 We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to measure relationships between scores from the FACIT-Sp-Ex with other variables.

Statement of Ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Demographics

Fifty-three participants with a SCI (39 males; 74%) were included in the study (aged 55.74±13.8 s.d. years; range 22–80 years). Thirty-seven control participants without SCI or pain (18 males; 49%) were also included (aged 62.81±16.22 s.d.; range 26–88 years). In the SCI group, 31 patients had complete SCI and 22 had incomplete SCI, 36 were paraplegic and 12 tetraplegic, whereas data regarding the level of injury were missing for five SCI participants. As there were only 3 participants without pain, it was decided to group into no or mild pain (0–3/10 NRS) or moderate-to-severe pain (4–10/10 NRS) on average over the previous week for most group comparisons. When divided into no or mild pain and moderate-to-severe pain, 23 participants described no or mild pain, whereas 30 participants described moderate-to-severe pain (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in age or gender when Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was applied.

Spiritual well-being (FACIT-Sp-Ex)

Spiritual well-being (as measured by the 23-item FACIT-Sp-Ex) was significantly lower in those with a SCI when compared with control participants without a SCI (54.0±19.6 s.d. versus 74.3±13.9 s.d.; P=0.00002). However, there was no significant difference in spiritual well-being between paraplegic and tetraplegic participants (56.2+19.0 versus 48.5+17.0, P=0.21). When the group with a SCI was split into those with no or mild pain (NRS 0–3; n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (NRS 4–10;n=30), there was no significant difference in spiritual well-being between the two groups (57.5±20.4 s.d. versus 51.0±20.4 s.d., P=0.12; Table 2).

As described previously, the 23-item FACIT-Sp-Ex can be divided into subscales: meaning/peace/purpose (items 1–8); faith (items 9–12); and relational aspects of spiritual well-being (items 13–23). When these subscales were analysed, a similar pattern to the findings with the overall FACIT-Sp-Ex score was found. There were significant differences between those with SCI and control participants in the mean scores for meaning (peace/purpose in life) (20.7±7.2 s.d. versus 27.7±7.2 s.d., P=0.00002), faith (comfort/strength in spiritual belief; 5.3.±5.2 s.d. versus 9.9±5.1 s.d., P=0.00007) and relational aspects (28.5.±8.9 s.d. versus 36.6±6.1 s.d., P=0.00001). There was also a significant difference between paraplegic and tetraplegic participants concerning faith (6.1+5.4 s.d. versus 2.8+3.6 s.d., P=0,04) but not for meaning (21.7+7.0 versus 19.0+6.1, P=0.22). However, there were no significant differences between the SCI group with no or mild pain compared with the group with moderate or severe pain on the meaning (23.7±6.4 s.d. versus 20.6.±7.2 s.d., P=0.472), faith (8.3±6.5 s.d. versus 5.1±5.1 s.d., P=0.38) and relational (30.0±9.5 s.d. versus 28.3.±8.9 s.d., P=0.88) subscales (Table 2).

Spiritual well-being (Spiritual Index of Well-being)

There were significant differences in scores using the Spiritual Index of Well-being in those with a SCI when compared with control participants without a SCI (52.3±10.3 s.d. versus 45.1±1.3 P=0.0003). When the SCI group was split into those with no or mild pain (n=20) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30), there was no significant difference between the two groups (47.1±8.7 s.d. versus 43.6±9.8 s.d., P=0.21; Table 2).

Mood

There were significant differences in depression scores between participants with and without a SCI as measured using the DASS-21 (10.2±9.3 s.d. versus 3.0±4.1 s.d., P=0.0003). There were no significant differences between paraplegic and tetraplegic participants in depression, anxiety or stress (Table 3). When the SCI group was split into those with no or mild pain (n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30), there was no significant difference between the two groups (7.4±5.8 s.d. versus 12.4±10.8 s.d., P=0.11; Table 2).

There were no significant differences between participants with SCI and controls in anxiety as measured using the DASS-21 (5.7±7.5 s.d. versus 3.4±6.4 s.d., P=0.58). When the SCI group was split into those with no or mild pain (n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30), there was no significant difference between the two groups (3.9±4.7 s.d. versus 7.1±9.0 s.d., P=0.27; Table 2).

There were no significant differences between participants with SCI and controls in stress as measured using the DASS-21 (10.1±9.2 s.d. versus 7.8±7.4; P<0.22). When the SCI group was split into those with no or mild pain (n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30), there was no significant difference between the two groups (7.6±7.4 s.d. versus 12.0±10.2 s.d., P=0.95; Table 2).

Interference with activities due to pain

There were significant differences between participants with and without a SCI and controls in activity interference due to pain as measured using the BPI (23.3±19.5 s.d. versus 1.9±3.2 P=0.00001). There were no significant differences between paraplegic and tetraplegic participants (24.4±19.6 versus 23.6±21.0, P=0.82). Further analysis comparing those with no or mild pain (n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30) found a significant difference between the two groups with a significantly higher level of pain-related disability in those in the moderate-to-severe pain group (7.2±7.2 s.d. versus 35.8±16.6 s.d., P=0.000001; Table 2).

Satisfaction with life

There were significant differences between participants with and without a SCI in satisfaction with life as measured using the SWL scale (17.11±7.6 s.d. versus 28.4±4.9; P=0.000001). There were no significant differences between paraplegic and tetraplegic participants (18.2+7.6 versus 14.7+7.0, P=0.17). When the group with a SCI was split into those with no or mild pain (n=23) and those with moderate or severe pain (n=30), there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups with a higher level of satisfaction with life in those with no or mild pain (19.6±8.0 s.d. versus 15.2±6.9 s.d., P=0.04; Table 2).

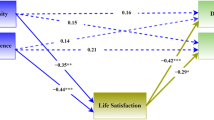

Relationships between spiritual well-being and other variables

There was a strong and statistically significant positive correlation between the total score on the FACIT-Sp-Ex spiritual well-being scale and satisfaction with life (r=0.69, P<0.000001) and pain self-efficacy (r=0.60, P<0.000001) and a moderate but statistically significant negative correlation between the total score on the FACIT-Sp-Ex scale and depression (r=−0.59, P<0.000001) and interference with activities (r=−0.48, P<0.000002). There was also a moderate but statistically significant negative correlation between the FACIT-Sp-Ex total score and pain intensity as measured by the NRS (r=−0.43, P<0.00002; Table 4). These relationships were almost identical when the shorter 12-item FACIT-Sp was used: satisfaction with life (r=0.68, P<0.0001), pain self-efficacy (r=0.60, P<0.0001), depression (r=−0.60, P<0.0001) and interference with life (r=−0.48).

When the FACIT-Sp was broken into two subscales (meaning/purpose/peace and faith), slight differences in the correlations were found (Table 4). There were strong and significant correlations between scores on the meaning/purpose/peace subscale and satisfaction with life (r=0.69, P<0.000001), pain self-efficacy (r=0.69, P<0.000001) and depression (r=−0.67, P<0.000001), a moderate but significant correlation with interference with life (r=−0.48, P<0.000002) and a moderate but significant negative correlation with pain intensity (r=−0.41, P<0.00001). On the other hand, when the faith subscale was used, there were weaker (although still statistically significant) correlations with satisfaction with life (r=−0.51, P<0.000001), depression (r=−0.40, P=0.00008), interference with life (r=−0.37, P<0.0002), pain self-efficacy (r=0.36, P<0.002) and pain intensity (r=−0.32, P<0.002).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that a SCI has a major negative impact on spiritual well-being or conversely is associated with high levels of spiritual distress. Our results also demonstrate that there is a significant relationship between spiritual well-being and pain in this group, with higher levels of pain associated with higher levels of spiritual distress. In addition, lower levels of spiritual well-being are associated with higher levels of depression and pain-related interference with activities and lower levels of pain self-efficacy and satisfaction with life.

High levels of spiritual distress in those with a SCI are consistent with the one previous study investigating this area, which used the same measure of spiritual well-being.15 Of note, both studies confirm that people with SCI have lower levels of spiritual well-being when compared with scores taken from other populations including cancer (breast and prostate), amputation, poliomyelitis and HIV/AIDS.15, 39, 40 Interestingly, the mean level of spiritual well-being in our group of people with a SCI was even lower than in the Tate and Forchheimer15 study (27.6 versus 34.5 mean scores FACIT-Sp).

Although there are previous data for comparison regarding spiritual well-being in people with a SCI,15 this is the first study investigating the impact of both SCI and pain on spiritual well-being. In line with our original hypothesis, a significant correlation was found between spiritual well-being and pain intensity. More specifically, lower levels of spiritual well-being globally and on each of the subscales of meaning, faith and relational aspects are all positively associated with higher levels of pain.

Of note, when groups with low (NRS11 0–3/10) and high levels of pain (NRS11 4–10/10) were compared, no significant difference was found. Although this does not match our correlation findings, the absence of an absolute difference between the two groups may be contributed to by a ‘floor effect’ due to the presence of a SCI with known high levels of spiritual distress masking any additional impact of pain. Insufficient power to detect a statistically significant difference is also likely given the high level of variability in spiritual well-being scores. A post hoc analysis revealed that more than 100 participants in each group would be necessary to detect a significant difference using these groupings.

Previous studies examining the relationship between pain intensity and spiritual well-being are mixed. Although some have shown a relationship between spirituality and pain intensity,41 others have shown that levels of spiritual well-being are more related to mood, pain tolerance and ability to cope rather than pain intensity itself.42 Whatever the specific link between spiritual well-being and levels of pain, there is certainly accumulating evidence showing spiritual well-being to be an important factor that is linked to mood, disability and satisfaction with life in people experiencing chronic pain.26, 43

It is not possible to determine the mechanisms responsible for this relationship between pain coping and spiritual well-being. However, one of the strongest relationships in this study was the positive correlation between pain self-efficacy and spiritual well-being and in particular the meaning and purpose subscale of the FACIT-Sp. Pain self-efficacy refers to a person’s confidence in engaging in activities despite the presence of pain31 and is also linked to resilience.44, 45 Therefore, there is a potentially interesting (although speculative) link between these different factors. The demonstrated positive association between spiritual well-being and pain self-efficacy may be due to the fact that people who have greater confidence in their ability to function at a higher level despite the presence of pain (or SCI) are able to engage in activities that give them a greater sense of meaning and purpose. In turn, this may enhance their coping and resilience.

One of the interesting and potentially very relevant findings from the study is the demonstration of a ‘cut-off’ or ‘threshold’ in the meaning component of the spiritual well-being scale, below which there is an increasing likelihood of poorer psychological status. Although it is not possible to determine direction of causality from this cross-sectional data, the findings nevertheless suggest that a score of 22 or lower on the meaning subscale of the FACIT-Sp is a strong ‘predictor’ of psychological dysfunction. This is particularly noticeable when examining the relationship between scores using the FACIT-Sp and the depression subscale of the DASS-21 (Figure 1). It can be seen that, with only two exceptions, those who scored 23 or above on the meaning subscale of the FACIT-Sp had scores on the DASS-21 depression scale that were 9 or less, which is regarded as in the normal range.30 However, scores of 22 and below on the meaning subscale of the FACIT-Sp were associated with a rising increase in DASS-21 scores, indicating rising levels of depression. In addition, low levels of meaning appeared to compound the effect of pain such that the only groups exhibiting severe depression were those with both moderate-to-severe pain and low levels of meaning (Figure 1). Although it would need to be examined more systematically, this suggests that a score of 22 or below on the meaning subscale of the FACIT-Sp may be a clinical indicator or flag for the presence of psychological dysfunction, particularly in those who have moderate or severe pain. Conversely, it fits with the writings of Viktor Frankl and others who suggest that having a strong sense of meaning and purpose is protective in the face of pain and suffering.46 This is line with our findings that indicate that spiritual well-being (and a strong sense of meaning and purpose in particular) enhances a person’s ability to cope with pain with reduced psychological distress.

Graph showing the relationship between depression and the meaning subscale of the FACIT-Sp divided into three groups: controls without SCI or pain; those with SCI and no or mild pain; and those with SCI and moderate or severe pain. The horizontal dashed line indicates the threshold for mild depression using the DASS questionnaire. Scores above this are regarded as being in mild, moderate or severely depressed range.30 The vertical dashed line indicates our proposed threshold for meaning using the FACIT-Sp. As can be seen, scores above this are almost all within the normal range for depression, and, scores below this are associated with increasing depression, particularly in those with severe pain.

The findings of this survey have relevance for clinical management. Within the subscales of the FACIT-Sp-Ex, it emerges that the most severely affected aspect is meaning and purpose (items 1–8). It is quite understandable that, for many people, a SCI with or without the presence of pain results in a major disability that can threaten a sense of meaning and purpose because of its impact on the ability to engage in activities that previously provided these things. However, given the clear link between spiritual distress and psychological dysfunction, particularly in the presence of pain, it supports the inclusion of assessment of spiritual well-being into routine clinical assessment. It also suggests that treatments that are designed to address issues of meaning and purpose may be an important component of enabling a person to build resilience and adapt to the presence of their injury.

In summary, a SCI is commonly associated with high levels of spiritual distress even in those who have low levels of pain. However, higher levels of pain are associated with even higher levels of spiritual distress. In addition, lower levels of spiritual well-being are associated with higher levels of depression and interference with activities and lower levels of pain self-efficacy and satisfaction with life. The demonstration that higher levels of spiritual well-being, including a sense of meaning and purpose, are ‘protective’ against increased psychological distress in the presence of pain indicates that identifying and assessing spiritual well-being is important. Furthermore, it suggests that developing strategies that enable people to have a greater sense of meaning and purpose will enable them to adapt to the presence of SCI and pain with better psychological health.

References

Jensen MP, Kuehn CM, Amtmann D, Cardenas DD . Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 638–645.

Störmer S, Gerner HJ, Grüninger W, Metzmacher K, Föllinger S, Wienke C et al. Chronic pain/dysaesthesiae in spinal cord injury patients: results of a multicentre study. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 446–455.

Richards JS, Meredith RL, Nepomuceno C, Fine PR, Bennett G . Psycho-social aspects of chronic pain in spinal cord injury. Pain 1980; 8: 355–366.

Summers JD, Rapoff MA, Varghese G, Porter K, Palmer RE . Psychosocial factors in chronic spinal cord injury pain. Pain 1991; 47: 183–189.

Budh CN, Osteraker A-L . Life satisfaction in individuals with a spinal cord injury and pain. Clin Rehabil 2007; 21: 89–96.

Nicholson Perry K, Nicholas MK, Middleton J . Spinal cord injury-related pain in rehabilitation: a cross-sectional study of relationships with cognitions, mood and physical function. Eur J Pain 2009; 13: 511–517.

Craig AR, Hancock KM, Dickson HG . A longitudinal investigation into anxiety and depression in the first 2 years following a spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 675–679.

Wollaars MM, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA, Brand N . Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain 2007; 23: 383–391.

Widerström-Noga EG, Duncan R, Turk DC . Psychosocial profiles of people with pain associated with spinal cord injury: identification and comparison with other chronic pain syndromes. Clin J Pain 2004; 20: 261–271.

Clark D . 'Total pain', disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med 1999; 49: 727–736.

Brooksbank M . Palliative care: where have we come from and where are we going? Pain 2009; 144: 233–235.

Rousseau P . Spirituality and the dying patient. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 2000–2002.

Breitbart W . Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002; 10: 272–280.

Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C . The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 2010; 24: 753–770.

Tate DG, Forchheimer M . Quality of life, life satisfaction, and spirituality: comparing outcomes between rehabilitation and cancer patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 81: 400–410.

Siddall PJ, Lovell M, MacLeod R . Spirituality: what is its role in pain medicine? Pain Med 2015; 16: 51–60.

Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Powell T . Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet 1999; 353: 664–667.

Koenig HG . Religion, spirituality and health: an American physician's response. Med J Aust 2003; 178: 51–52.

Sulmasy DP . A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 24–33.

Selman L, Harding R, Gysels M, Speck P, Higginson IJ . The measurement of spirituality in palliative care and the content of tools validated cross-culturally: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 41: 728–753.

Tanyi RA . Towards clarification of the meaning of spirituality. J Adv Nurs 2002; 39: 500–509.

Chochinov HM, Cann BJ . Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. J Palliat Med 2005; 8: S103–S115.

Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ . A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003; 103: 249–257.

Strang P . Existential consequences of unrelieved cancer pain. Palliat Med 1997; 11: 299–305.

Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG . Religiousness and spirituality in fibromyalgia and chronic pain patients. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2008; 12: 327–332.

Dezutter J, Robertson LA, Luyckx K, Hutsebaut D . Life satisfaction in chronic pain patients: the stress-buffering role of the centrality of religion. J Sci Study Relig 2010; 49: 507–516.

Cotton S, Puchalski C, Sherman S, Mrus J, Peterman A, Feinberg J et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21: S5–S13.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS . Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain 2004; 20: 309–318.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH . The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995; 33: 335–343.

Nicholas MK . The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007; 11: 153–163.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S . The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985; 49: 71.

Pavot W, Diener E . The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol 2008; 3: 137–152.

Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D . A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 1999; 8: 417–428.

Bredle MJ, Salsman JM, Debb SM, Arnold BJ, Cella D . Spiritual well-being as a component of health-related quality of life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions 2011; 2: 77–94.

Frey BB, Daaleman TP, Peyton V . Measuring a dimension of spirituality for health research: validity of the spirituality index of well-being. Res Aging 2005; 27: 556–577.

Daaleman TP, Frey BB . The spirituality index of well-being: a new instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med 2004; 2: 499–503.

Keselman HJ, Games PA, Rogan JC . Protecting the overall rate of Type I errors for pairwise comparisons with an omnibus test statistic. Psychol Bull 1979; 86: 884–888.

Kinney C, Rodgers D, Nash K, Bray C . Holistic healing for women with breast cancer through a mind, body, and spirit self-empowerment program. J Holist Nurs 2003; 21: 260–279.

Peterman A, Fitchett G, Brady M, Hernandez L, Cella D . Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002; 24: 49–58.

Lucchetti G, Lucchetti AG, Badan-Neto AM, Peres PT, Peres MF, Moreira-Almeida A et al. Religiousness affects mental health, pain and quality of life in older people in an outpatient rehabilitation setting. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 316–322.

Wachholtz A, Pearce M . Does spirituality as a coping mechanism help or hinder coping with chronic pain? Curr Pain Headache Rep 2009; 13: 127–132.

Nsamenang SA, Hirsch JK, Topciu R, Goodman AD, Duberstein PR . The interrelations between spiritual well-being, pain interference and depressive symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med 2016; 39: 355–363.

Craig A . Resilience in people with physical disabilities Kennedy P The Oxford Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA. 2012.

Bonanno GA, Westphal M, Mancini AD . Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011; 7: 511–535.

Frankl VE . Man's Search for Meaning. Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA. 1946.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant funding from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siddall, P., McIndoe, L., Austin, P. et al. The impact of pain on spiritual well-being in people with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 55, 105–111 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.75

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.75

This article is cited by

-

Association of pain management and positive expectations with psychological distress and spiritual well‑being among terminally ill cancer patients admitted to a palliative care unit

BMC Nursing (2023)

-

Australian Patient Preferences for the Introduction of Spirituality into their Healthcare Journey: A Mixed Methods Study

Journal of Religion and Health (2023)

-

The Effect of Spiritual Well-being on Hope in Immobile Patients Suffering From Paralysis Due to Spinal Cord Injuries

Journal of Religion and Health (2022)

-

Longitudinal changes in spiritual well-being and associations with emotional distress, pain, and optimism–pessimism: a prospective observational study of terminal cancer patients admitted to a palliative care unit

Supportive Care in Cancer (2021)

-

The role of spirituality in spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation: exploring health professional perspectives

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)