Abstract

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives:

(1) To examine the association between social participation (SP) and social support (SS) with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction and (2) to explore the joint association and interactions of SP and SS with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction in community-dwelling adult men with spinal cord injury.

Setting:

Members of the Spinal Injuries Japan organization.

Methods:

We sent questionnaires to 2731 registered members of Spinal Injuries Japan via mail. Responses from 625 men aged ⩾40 years were analyzed. Respondents were categorized into four groups: SP/sufficient SS, SP/insufficient SS, no SP/sufficient SS and no SP/insufficient SS. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the odds ratios for self-rated health and dietary satisfaction according to the SP/SS categories.

Results:

Relative to participants in the no SP/insufficient SS category, those in the SP/sufficient SS group demonstrated significantly better self-rated health and dietary satisfaction after adjusting for sociodemographic variables. There was no interaction between SP and SS in self-rated health or dietary satisfaction. SP was associated with high self-rated health without SS, and sufficient SS was associated with high dietary satisfaction without SP.

Conclusions:

Relative to other groups, participants with SP/sufficient SS demonstrated higher self-rated health and dietary satisfaction. Sufficient SS was associated with high dietary satisfaction without SP. This study suggested the importance of addressing aspects of both SP and SS using self-rated health and dietary satisfaction as outcome measures in health promotion programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) are more likely to experience preventable health risk factors such as obesity, physical inactivity and smoking relative to individuals without disabilities.1, 2 Many individuals with SCI participate socially (for example, through study or work) while leading an unassisted home life. Health promotion programs for community-dwelling adults with SCI reduce the risk of chronic disease, maintain health and enable individuals to enjoy high quality of life.

Both social participation (SP) and social support (SS) are social determinants of health3, 4 and are indispensable to health promotion programs. SP is defined as activities and participation, learning and applying knowledge, general tasks and demands, communication, mobility, self-care, domestic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships in major life areas and community/social and civic life in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.5 Several reports have suggested that SP increased healthy behavior6 and self-rated health7 in elderly individuals. SP is strongly recommended as a means of health promotion in individuals with disabilities.8

Numerous studies have reported that SS contributes to health promotion.9, 10, 11 SS is described as ‘aid and assistance exchanged through social relationships and interpersonal transactions.’12 SS is divided into four broad types, namely emotional, instrumental, appraisal and informational support, and it is defined interpersonal transaction as inclusive of at least one of these four types.13 SS has been associated with increased physical activity and vegetable and fruit intake.10, 11 In addition, an intervention program to promote SP and SS in community-dwelling adults with SCI was found to be more likely to promote healthy lifestyles.8, 14

There is a possibility that self-rated health could be used to evaluate physical function, illness and mental health and social function15 and may be a predictive factor for mortality.16 Therefore, self-rated health was used as an outcome in the health promotion intervention.

Dietary lifestyle is an important element in planning health promotion programs. Interventions that focus on dietary lifestyle require evaluation of diet-related quality of life. One of the subscales of the Subjective Diet-Related quality of life Scale includes dietary satisfaction.17 High dietary satisfaction has been shown to be related to healthy dietary behavior (for example, heeding regarding the diet and eating sufficient vegetables) in community-dwelling individuals with SCI.18 Measurement of dietary satisfaction is useful in examining health promotion programs associated with healthy dietary behavior or predisposing factors.

Both SP and SS are social determinants of health. We hypothesized that SP and SS would also be related to self-rated health and dietary satisfaction in community-dwelling adults with SCI. Intervention programs designed to promote both SP and SS could be expected to exert a strong effect on health promotion. In developing an effective program, it is necessary to clarify the relationship between health promotion outcomes and SP and SS. However, to our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to examine the association between SP and SS with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction in community-dwelling adults with SCI. With respect to promoting SP and SS programs simultaneously, a synergistic effect may occur in the evaluation of self-rated health and dietary satisfaction, and consideration of this effect is valuable in the development of effective health promotion programs. Therefore, this study aimed to (1) examine the association between SP and SS with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction and (2) explore the joint association and interactions of SP and SS with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and procedures

We used a cross-sectional study design. The target group included community-dwelling individuals with SCI. In September 2011, we sent questionnaires to 2731 registered members of the Spinal Injuries Japan organization via mail. Spinal Injuries Japan has 45 branch offices across the country; they perform activities such as reporting on SCI and offering peer support. With regard to the attributes of registered members, the average age is approximately 65 years, 80% are men, 20% are women and the most common lesion type is thoracic SCI, followed by cervical cord and lumbar SCI.

Measurements

(1) Exposure variables: SP and SS

We asked one question, which was also used in the Japanese National Health and Nutrition Survey 2008,19 to examine SP. This question was: ‘In the past year, have you participated in the following independent activities individually, with a friend or as part of a group?’ Respondents chose the most applicable of nine responses (hobby, health/sport, production/work, education/culture, social climate improvement, safety management, welfare, community event and no participation). SP was dichotomized into participation (respondents chose one of the following eight activities: a hobby, health/sport, production/work, education/culture, improvement of social climate, safety management, welfare and a community event) and no participation (respondents chose no participation).

The question used to examine SS was: ‘Are the people around you (including family members) supportive of your efforts to maintain your health?’ The possible responses to this question were always, sometimes, seldom and never, with SS dichotomized into sufficient support (always) and insufficient support (sometimes, seldom and never).

(2) Outcome variables: self-rated health and dietary satisfaction

The question regarding self-rated health was: ‘How would you assess your current health condition?’ The possible responses to this question were very good, good, fair and poor. Self-rated health was dichotomized into good (very good with good) and poor (fair with poor). The question regarding dietary satisfaction was: ‘How would you describe your satisfaction with your current diet?’ The possible responses to this question were high, moderate, low and very low. Dietary satisfaction was dichotomized into high (high) and low (moderate, low and very low).

(3) Sociodemographic variables

Data regarding participants’ sex, age(40–55; 56–70; or ⩾71 years), years since injury (⩽9; 10–19; 20–29; 30–39; or ⩾40 years), lesion type (cervical cord injury, thoracic SCI or lumbar SCI), living status (living alone or living with others), current employment status (working: yes or no) and current use of welfare services and support (yes or no) were obtained from the completed questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

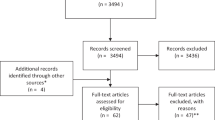

We received responses from 1000 individuals (37% response rate) but excluded responses in which crucial data such as sex, age, lesion type, type of disability, SP and SS, self-rated health and dietary satisfaction were missing and a small number of responses from women and young men. Ultimately, responses from 625 men aged ⩾40 years were analyzed (23% valid response rate).

Respondents were categorized into four groups: SP/sufficient SS, SP/insufficient SS, no SP/sufficient SS and no SP/insufficient SS. The associations between the four groups and sociodemographic variables were analyzed using a X2-test. Correlations between SP and SS and self-rated health and dietary satisfaction were examined using binominal logistic regression analysis. To measure the individual effects of SP and SS, the no SP (in the case of SP) and insufficient SS (in the case of SS) group was used as the reference group in the analysis. Adjusted variables were age, years since injury, lesion type, living status, current employment status, current use of welfare services and support, SS (in the case of SP) and SP (in the case of SS). Logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) for self-rated health and dietary satisfaction according to the four SP/SS groups adjusted for age, years since injury, lesion type, living status, current employment status and current use of welfare services and support. To measure the combined effects of SP and SS, the no SP/insufficient SS group was used as the reference group for each self-rated health and dietary satisfaction variable in the analysis. We also examined the two-way interaction between SP and SS. The dependent variables were self-rated health and dietary satisfaction. The independent variable was the product terms created by SP and SS. Logistic regression analysis was performed, and the adjusted variables were age, years since injury, lesion type, living status, current employment status, current use of welfare services and support, SP and SS. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan); the level of significance was set at 5% for the two-tailed tests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethical committee of Tokyo Metropolitan University.

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

The subjects’ mean age was 62.7 (s.d.=9.9) years. The mean number of years since injury was 28.1 (12.6) years. Of the total respondents, 51.7%, 29.3% and 19.0% had suffered thoracic, cervical and lumbar injuries, respectively. The proportion of subjects who demonstrated SP was 67.5%. In addition, with respect to the question regarding SS, 55.4%, 35.2%, 7.0% and 2.4% of the subjects responded that they always, sometimes, seldom and never received support, respectively. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the total sample and the individual SP/SS groups. Significant differences were observed between groups according to age and living status.

Table 2 contains self-rated health and dietary satisfaction information for the total sample and individual SP/SS groups. Of the subjects who responded ‘high’ for the dietary satisfaction item, 43.1% were in the SP/sufficient SS group, 34.3% were in the no SP/sufficient SS group, 10.4% were in the SP/insufficient SS group and 6.3% were in the no SP/insufficient SS group.

Table 3 contains the ORs for self-rated health and dietary satisfaction according to SP and SS. High self-related health (OR: 1.76) was more likely in participants with SP relative to those with no SP; however, there was no significant association between SP and dietary satisfaction. High self-rated health (OR:1.86) and dietary satisfaction (OR: 6.53) were more likely in participants with sufficient SS relative to those with insufficient SS.

Table 4 shows the ORs for self-rated health or dietary satisfaction according to the SP/SS group. The SP/sufficient SS and reference groups differed significantly with respect to self-rated health and dietary satisfaction, and the OR for SP/sufficient SS was higher relative to that for the reference group. SP/sufficient SS was significantly associated with self-rated health, whereas no SP/insufficient SS was significantly associated with dietary satisfaction. There were no interactions between SP and SS with respect to self-rated health or dietary satisfaction.

Discussion

In community-dwelling men with SCI, the SP/sufficient SS group was most likely to demonstrate high self-rated health and dietary satisfaction relative to the other SP/SS groups. However, there was no synergistic effect observed for combined SP and SS. SP/sufficient SS was significantly associated with self-rated health, whereas no SP/insufficient SS was significantly associated with dietary satisfaction. These results indicate that self-related health should be used as an outcome measure in intervention programs to promote SP, and dietary satisfaction should be used as an outcome measure in intervention programs to promote SS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to clarify the association between SP and SS using self-rated health and dietary satisfaction. Our results could inform interventions and health promotion programs for community-dwelling adults with SCI.

In a previous study involving elderly individuals, SP was found to be related to decreased risk of reduced capacity for activities of daily living in the future20 and increased physical activity and opportunities to leave the home.6 SP is recommended as a means of promoting health in individuals with disabilities (for example, studies, occupations, sports and local activities).8 Self-rated health consists of physical function, mental health and social function.15 The association between SP and self-rated health in this study suggests that programs to promote SP may enhance self-rated health in community-dwelling adults with SCI.

Sufficient SS showed significantly high ORs for both self-rated health and dietary satisfaction (Table 3). Dietary satisfaction has been associated with healthy dietary behavior in community-dwelling individuals with SCI.18 In addition, SS has been reported to be related to increased intake of vegetables and fruit.10, 11 SS intervention programs should encompass self-rated health,15 healthy dietary behavior and dietary satisfaction.18

The SP/sufficient SS group demonstrated the highest ORs for self-rated health and dietary satisfaction relative to the other groups (Table 4). However, there was no interaction observed between SP and SS; therefore, the hypothesis that a synergistic effect would be found was not supported in this study. SP was associated with high self-rated health without SS (Table 4), but the OR was low (OR: 1.78; P=0.043), and further examination of this relationship is required. Sufficient SS was associated with high dietary satisfaction without SP (Table 4). The results of this study suggested that it is necessary to evaluate both self-related health and dietary satisfaction in health promotion intervention programs for SP and SS; SS intervention programs are required to evaluate dietary satisfaction, and SP intervention programs are required to evaluate self-rated health.

The study was subject to several limitations. First, the study used a cross-sectional design; therefore, it was not possible to make causal inferences regarding SS and SP with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction. Second, 45 employed subjects (7.3%) responded with ‘no participation’ (Table 1). Third, the type of support involved in health promotion was not ascertained with the SS question, ‘Are the people around you (including family members) supportive of your efforts to maintain your health?’ Fourth, the population from which SCI participants were recruited comprised men aged ⩾40 years who were members of the Spinal Injuries Japan organization. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of the overall population of individuals with chronic SCI in Japan. In addition, socioeconomic background information (for example, annual income and education level) was not obtained. Furthermore, we did not analyze data from nonresponders or those who returned questionnaires with missing data. Future research should focus on increasing response rates. Fifth, we did not obtain data regarding levels of injury as defined by the America Spinal Injury Association classifications A or B (motor complete SCI). Sixth, the dietary satisfaction question used had not been validated as an outcome measure. Finally, the distribution for the independent and dependent variables was recorded and they were dichotomized, but they were not validated.

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight the importance of addressing aspects of both SP and SS using self-rated health and dietary satisfaction as outcome measures. SP and SS vary according to country, area, race and culture. However, the Japanese population’s long life expectancy at birth and overall good health are well known worldwide. Our findings are important to the field of health promotion for community-dwelling individuals with SCI. This research has identified the need to address the following two issues. The first involves the clarification of the types of SS that are easily accessible, namely emotional, instrumental, appraisal and informational support, to increase dietary satisfaction in community-dwelling individuals with SCI. The second involves clarification of the types of SP that are effective in promoting high self-rated health, including hobbies, health/sport, production/work and education/culture.

In conclusion, SP was related to high self-rated health, and SS was related to high self-rated health and high dietary satisfaction in community-dwelling Japanese men with SCI. High self-rated health and dietary satisfaction were more likely in the SP/sufficient SS group relative to the other SP/SS groups. Sufficient SS was associated with high dietary satisfaction without SP.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen SA, Garrison A, Tun CG, Gagnon D et al. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 408–416.

de Groot S, Post MW, Snoek GJ, Schuitemaker M, van der Woude LH . Longitudinal association between lifestyle and coronary heart disease risk factors among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 314–318.

World Health Organization Social Participation. Social Determinants Of Health http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/countrywork/within/socialparticipation/en/ Accessed 5 June 2015.

Wilkinson R, Marmot M (eds) Social Determinants Of Health: The Solid Facts, 2nd edn, World Health Organization. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark. 2003 Available from http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf accessed 5 June 2015.

World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). World Health Organization. 2002. Available from http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 5 June 2015.

Fujiwara Y, Sugihara Y, Shinkai S . Effects of volunteering on the mental and physical health of senior citizens: significance of senior-volunteering from the view point of community health and welfare. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2005; 52: 293–307.

Ichida Y, Hirai H, Kondo K, Kawachi I, Takeda T, Endo H . Does social participation improve self-rated health in the older population? A quasi-experimental intervention study. Soc Sci Med 2013; 94: 83–90.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to improve the health and wellness of persons with disabilities: calling you to action. Office of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services: : Washington, DC, USA. 2005.

Seeman TE, Berkman LF . Structural characteristics of social networks and their relationship with social support in the elderly: who provides support? Soc Sci Med 1988; 26: 737–749.

Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeh MC, Resnicow K . Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2008; 34: 535–543.

Tamers SL, Beresford SA, Cheadle AD, Zheng Y, Bishop SK, Thompson B . The association between worksite social support, diet, physical activity and body mass index. Prev Med 2011; 53: 53–56.

Heaney CA, Israel BA . Social networks and social support. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K (eds) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th edn, Jossey-Bass:: San Francisco, NY, USA., 2008, pp 189–210.

House JS . Work Stress and Social Support. Addison Wesley Publishing Company: : Reading, MA, USA,. 1981.

Rimmer JH, Wang E, Pellegrini CA, Lullo C, Gerber BS . Telehealth weight management intervention for adults with physical disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 92: 1084–1094.

Idler EL, Kasl S . Health perceptions and survival: do global evaluations of health status really predict mortality? J Gerontol 1991; 46: S55–S65.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y . Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997; 38: 21–37.

Ainuki T, Akamatsu R, Hayashi F, Takemi Y . The reliability and validity of the Subjective Diet-related Quality of Life (SDQOL) Scale among Japanese adults. Jpn J Nutr Diet 2012; 70: 181–187.

Hata K, Inayama T . Associations between dietary satisfaction and food intake, behavioral, and dietary environmental factors in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury. Jpn J Nutr Diet 2013; 71: 138–144.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2008. Tokyo; 2011. (in Japanese).

Ishizaki T, Watanabe S, Suzuki T, Shibata H, Haga H . Predictors for functional decline among nondisabled older Japanese living in a community during a 3-year follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1424–1429.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the individuals with SCI who participated in this study. This work was supported by JSPSKAKENHI Grant Number 23500962.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hata, K., Inayama, T., Matsushita, M. et al. The combined associations of social participation and support with self-rated health and dietary satisfaction in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 54, 406–410 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.166

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.166

This article is cited by

-

Influence of social participation and support on self-rated health among Chinese older adults: Mediating role of coping strategies

Current Psychology (2023)

-

Oral health and depressive symptoms among older adults in urban China: a moderated mediation model analysis

BMC Geriatrics (2022)

-

The association between health-related quality of life/dietary satisfaction and perceived food environment among Japanese individuals with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2017)