Abstract

Study design:

This is a prospective open-cohort case series.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to assess changes over time in the duration of key acute hospital process barriers for patients with spinal cord damage (SCD) from admission until transfer into spinal rehabilitation unit (SRU) or other destinations.

Setting:

The study was conducted in Acute hospitals, Victoria, Australia (2006–2013).

Methods:

Duration of the following discrete sequential processes was measured: acute hospital admission until referral to SRU, referral until SRU assessment, SRU assessment until ready for SRU transfer and ready for transfer until SRU admission. Time-series analysis was performed using a generalised additive model (GAM). Seasonality of non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (SCDys) was examined.

Results:

GAM analysis shows that the waiting time for admission into SRU was significantly (P<0.001) longer for patients who were female, who had tetraplegia, who were motor complete, had a pelvic pressure ulcer and who were referred from another health network. Age had a non-linear effect on the duration of waiting for transfer from acute hospital to SRU and both the acute hospital and SRU length of stay (LOS). The duration patients spent waiting for SRU admission increased over the study period. There was an increase in the number of referrals over the study period and an increase in the number of patients accepted but not admitted into the SRU. There was no notable seasonal influence on the referral of patients with SCDys.

Conclusions:

Time-series analysis provides additional insights into changes in the waiting times for SRU admission and the LOS in hospital for patients with SCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient flow problems are acknowledged as major problems in emergency departments1 and acute care hospitals2, 3 in many countries. This challenge will quite likely become harder to manage with population ageing in the decades ahead.4 There has been comparatively little attention to examining the barriers for acute hospital patients waiting for inpatient rehabilitation,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 or discharge barriers for rehabilitation patients remaining in hospital after they no longer need inpatient rehabilitation.8, 10 These barriers reduce bed availability for other patients and increase the risk of iatrogenic11 or impairment-related complications.5, 12

People with spinal cord damage (SCD) from any cause—either traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) or non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (SCDys)—need optimal care from the onset of their SCD in order to prevent secondary complications. Patients have improved outcomes with a specialised and systematic approach to their care.12, 13

A number of studies have highlighted the problem faced by some patients with SCD who have barriers for admission into a specialised spinal rehabilitation unit (SRU),5, 6, 14, 15 and this has been highlighted as an international issue.16 We have recently reported the duration of process barriers for patients with SCD in acute hospital, the variables that influenced them, along with the impact on a range of outcomes.17 That study, however, used the pooled waiting times for the different processes and did not explore whether there were any changes in the process barriers over time or whether there was any seasonal influence on referral patterns. These are important because if system changes were implemented to address the process barriers, the pooling of results would mask these. Furthermore, there are no previous reports in the literature of seasonal variation in the occurrence or referral of patients with SCDys.

The primary objective of this study was to perform a time-series analysis of the duration of the process barriers for patients with SCD admitted to acute hospital who need admission into an SRU. A secondary objective was to explore whether there was any seasonality in the referral of patients with SCDys.

Materials and Methods

Setting

The SRU at Caulfield Hospital, Victoria, Australia is a 12-bed adult inpatient unit located in a public hospital and funded by the State. Patients are referred from both private and public hospitals from greater metropolitan Melbourne and elsewhere in the State.

The subjects of this study have been described previously in the report mentioned above concerning process barriers for patients with SCD in acute hospital and referred to the SRU.17 Additional details regarding the setting of the study, the typical patient pathway from onset of SCD to admission into SRU, participants and background to the outcome measures, and data collection and storage are given in this previous publication.

Study design

This was a prospective open-cohort case series of patients with SCD consecutively referred to the SRU between 1 September 2006 and 31 July 2013.

Participants

All patients with a recent onset of SCD who were referred and accepted for admission into the SRU were included in the study. Patients with a chronic SCD re-admitted to acute hospital for management of late-onset complications after a previous rehabilitation admission were excluded. There was no selection bias regarding the aetiology of a patient’s SCD.

Outcome measures

The duration of sequential non-overlapping key processes from acute hospital admission until transfer into SRU were recorded, along with key demographic and clinical data. The following key processes were recorded: acute hospital admission (or onset of SCD if after admission) until referral to SRU, referral until assessment by the SRU, assessment by SRU until deemed ready for transfer to rehabilitation and ready for transfer until SRU admission, or other destination. These key processes are based on previous research.18, 19 In addition, the following were also recorded: presence of a pelvic region pressure ulcer on admission to SRU; referral source (same health network as the SRU or another network); age on admission to acute hospital (years); gender; level of SCD (tetraplegia or paraplegia); aetiology of SCD (traumatic SCI or non-traumatic SCDys); American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grade of injury;20 and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM).21 The latter two measures were recorded on admission and discharge from the SRU, for those patients who were admitted there.

Statistical analysis

A semi-parametric Poisson regression model was used to examine the association between outcome variables with the seven covariates (dependant variables) using a generalised additive model (GAM).22, 23 The GAM method is a flexible and effective approach for performing non-linear regression analysis in time-series studies. It allows nonparametric adjustments for non-linear confounding effects of seasonality and trends. It is more flexible than parametric linear regression—which forces linearity—because using GAM methods the results are data-driven, and the resulting fitted values do not come from a priori model. The data determine the shape of the response curve and smoothing functions are applied, with the degree of smoothing controlled by degrees of freedom.

We developed a base model with a smooth age (that is, non-linear effect of age). The other six covariates were as follows: gender (male reference category), level of SCD (paraplegia reference category), AIS on admission (AIS D as the reference category), referral source (parent network as the reference category), pelvic region pressure ulcer on SRU admission (pressure ulcer present was reference category) and admission FIM motor subscale. The non-linear associations were fitted using a GAM approach. Penalised regression splines were used to estimate smooth terms (automatic selection) in the models using the GAM function in the mgcv package of R.24 Diagnostic plots were checked for model fit and distribution of residuals.

Time-series data can exhibit a variety of patterns, and it is helpful to categorise some of these. Time-series decomposition involves separating a time series into several distinct components. There are three components that are typically of interest: trend component, seasonal component and the remainder or irregular component. A trend exists when there is a long-term increase or decrease in the data. It does not have to be linear. Sometimes a trend changes direction from an increasing trend to a decreasing trend. A seasonal pattern exists when a series is influenced by seasonal factors (for example, the quarter of the year, the month or day of the week). Seasonality is always of a fixed and known period. The remainder or irregular component is what remains when the seasonal and trend components have been subtracted from the data. We had no prior hypothesis as to whether there would be any seasonality influence on the referral of people with non-traumatic SCDys.

All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. The project was approved by the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee. P-values of <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/) software version 3.1.0.25

Results

As previously reported,17 there were 347 patients ranging in age from 17 to 93 years (median 65, interquartile range [IQR] 52–76) referred to the SRU during the study period and who were included in the analysis. There were slightly more male patients (n=203, 58.5%), and most patients had SCDys (n=280, 80.7%), paraplegic level of injury (n=267, 77%) and a third of patients were motor incomplete (AIS grade D; n=95, 33.4%). Most (n=210, 60.5%) of the patients where referred from acute hospitals in other health networks to that which the SRU is affiliated. There was a median of 12 days (IQR 6–20) from acute hospital admission until referral, a median of 1 day (IQR 0–2) from referral until SRU assessment, a median of 0 (IQR 0–3.5) days from assessment deemed ready and a median of 7 (IQR 2–20) days from deemed ready until transfer to SRU, or other destination. Further details regarding these patients are reported elsewhere.17

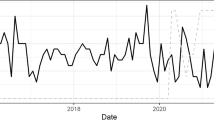

The results of the regression model are shown in Table 1, and Figure 1 presents the non-linear effect of age on key waiting periods. These graphs are plotted using results from fitted non-linear GAM regression models. The time patients spent waiting for admission was 22% longer for female patients, 26% longer in those with tetraplegia, 38% longer for patients with a pressure ulcer on admission, 26% shorter in those with AIS grade D on admission, 81% longer for patients referred from another network and 0.6% shorter for every increase in the FIM motor score. Age was related to the duration of waiting for admission in a non-linear relationship (Figure 1a). The waiting period increased as the patients’ age increased from 20 to around 35 years, and then reduced as the patients become older towards 80 years of age. In this and the other two components of Figure 1, the wide confidence interval at the extremes is because of the low number of patients at the extremes of age, and the apparent trend should be disregarded at the extremes. The duration of both the acute hospital and SRU length of stay (LOS) was higher for female patients (9% longer in acute and 25% longer in SRU), higher if patients had tetraplegia (14% longer in acute and 13% longer in SRU) and shorter for patients with AIS grade D spinal damage (45% acute and 16% in SRU). The SRU LOS was 39% longer if there was a pressure ulcer on admission, 18% shorter for those referred from the parent network and shorter if they were less disabled on admission (2.4% shorter for every one point increase in FIM motor score). Age had a non-linear influence on both the acute hospital LOS (Figure 1b) and SRU LOS (Figure 1c).

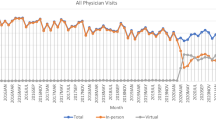

The changes over the study period regarding the number of patients in different situations and the duration of various waiting states are shown in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The graphs all used quarterly data to optimise the smoothing of variation in events because of the relatively low number of patients.

The time patients spent waiting for admission into the SRU showed no change over time for patients referred from the parent network, but for patients in other networks there was a trend towards an increasing duration of waiting for admission over time along with increasing volatility, Figure 2.

The duration of the key process barriers for patients in acute hospitals is shown in Figure 3. There were no apparent changes in the duration of ‘referral to assessment’ and the ‘assessment completed to ready’ waiting times. There was a trend towards increasing duration of the ‘admission to referral’, but it is important to note that the high peak in 2010 was because of a single patient. There was a trend towards increasing duration and volatility of the ‘ready until admission into the SRU’ waiting period.

The number of patients referred to the SRU showed a linear increase for the parent network that appeared to stabilise in the first quarter of 2011. The number referred from the non-parent networks showed a non-linear increase over time until 2011 and then there was a reduction (Figure 4).

There was a linear increase over time in the number of patients admitted into the SRU until late 2012 and then the number decreased, whereas the number not admitted into the SRU showed a linear increase over the study period with periods of volatility (Figure 5).

Periods with an increased number of referrals appeared to coincide with more patients not being admitted to the SRU. There did not, however, appear to be a relationship between the peaks in these two events and the waiting time for admission into the SRU (Figure 6).

The seasonal variation in the number of patients with non-traumatic SCDys referred to the SRU is shown in Figure 7. The top panel presents the raw data, showing relative stability over time. The grey bar on the right side of the y-axis shows the relative contribution of the different components of the data. The smaller the bar length the larger the contribution, indicating that the seasonal influence was very small in comparison with the trend influence.

Discussion

Age had a non-linear effect on the acute and SRU LOS and the duration of time spent waiting for transfer from acute hospital to SRU. The time patients spent waiting for admission into the SRU increased over the study period, and this was primarily as a result of the increase in the waiting time for patients referred from hospitals in other health networks to the parent network. There was an increase in the number of referrals over the study period, but also an increase in the number of patients who were accepted but subsequently not admitted into the SRU. There was no notable seasonal influence on the referral of patients with SCDys.

The GAM regression results presented here have both similarities and differences when compared with the linear regression results reported previously for these patients.17 In the linear regression model, only being female, referral from another health network and having a pelvic region pressure ulcer were significant influences on the waiting for a SRU bed after being deemed ready for transfer, whereas in the GAM analysis we found that in addition to these variables the level, grade and admission motor FIM were significant influences on the waiting period. The linear regression of factors influencing the SRU LOS found that the time patients spent waiting for a SRU bed and the admission motor FIM were the only significant variables, whereas in contrast the GAM analysis found that significant increases in the SRU LOS were associated with being female, having tetraplegia, being motor complete, referral from another health network, pressure ulcer on admission and those who were more disabled.

It was not possible to explain why female patients had a longer wait for admission into the SRU and a longer LOS in acute hospital. Gender role issues and females potentially being less likely to have a male partner able to care for them are possible explanations for the gender influence on the SRU LOS. It is believed that patients with tetraplegia and complete SCD had a longer LOS in acute and SRU because of their higher disability and greater chance of spinal cord-related complications. Because those with tetraplegia and AIS grades A, B or C would have been more likely to require a hoist for transferring when in acute hospital and the limited capacity of the SRU to manage these patients, as has been reported recently,16 some patients would have waited for a bed because of the limitations of the physical environment and staffing. This was not formally assessed as part of the project. The impact of pressure ulcers on extending SRU LOS is not unexpected.26 The association of pressure ulcers with the waiting time for transfer from acute hospital to SRU may be a cause or an effect of the delay.

We are not able to explain the influence of age on the wait for admission to the SRU after patients were deemed ready for transfer, the LOS in SRU or why younger patients had a longer acute hospital LOS.

There was no seasonality component to the referral of patients with SCDys for rehabilitation. In some ways this is not surprising, given the heterogeneous nature of the aetiology of this condition,27, 28 but it has not been studied previously. There may, however, be seasonality factors influencing variables that have an impact on the aetiology of certain SCDys (for example, infections), but the number of patients was too small to assess the seasonality by specific aetiologies of SCDys. We did not assess seasonality in the referral of patients with traumatic SCI because the number in our sample was too small for this analysis and seasonality has been examined in previous studies of traumatic SCI.

The strengths of this project include that, as far as we are aware, this is the first study that has used GAM and time-series analysis to examine changes over time in hospital process barriers that influence the flow of patients with SCD. It is also the first time that seasonality in patients with SCDys has been studied.

A limitation of this study is that data were limited to a single centre. In addition, as there is no other similar research involving patients with SCD with which we can compare our findings, we are limited in our ability to contrast our results with others and put them into a National or international context.

It is not possible to generalise the findings of this study to other settings because of the unique nature of our SRU, the referral sources and the health system within which it operates.29 However, it is crucial to highlight that one of the main points that we wish to make is that the study methods can be generalised. Other researchers can also use the same methods that we have used to help better understand patient flow problems and to identify inefficiencies, as well as monitor improvements.

There are a number of implications for future research from this study. These include that strategies should be explored to address the main process barriers identified, namely, the delay between admission to acute hospital and referral to SRU, the barriers to admitting patients into the SRU in a more timely manner and the increasing number of patients not able to be admitted. It is intended to repeat this analysis in the future after process improvements have been implemented. Researchers in spinal cord medicine should consider using GAM and time-series analysis, with the assistance of statisticians familiar with these methods, where these methods are appropriate in order to obtain alternative analyses that offer advantages over more familiar techniques.

In conclusion, it is suggested that prospectively monitoring the key process barriers, in particular waiting for a SRU bed and SRU LOS, in real time, will facilitate the earlier detection of significant variation. This will then allow strategies to address these barriers to be implemented in a more timely manner.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Eitel DR, Rudkin SE, Malvehy MA, Killeen JP, Pines JM . Improving service quality by understanding emergency department flow: a white paper and position statement prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med 2010; 38: 70–79.

Weaver FM, Guihan M, Hynes DM, Byck G, Conrad KJ, Demakis JG . Prevalence of subacute patients in acute care: results of a study of VA hospitals. J Med Syst 1998; 22: 161–172.

Flintoft VF, Williams Jl, Williams RC, Basinski AS, Blackstien-Hirsch P, Naylor CD . The need for acute, subacute and nonacute care at 105 general hospital sites in Ontario. Joint policy and planning committee non-acute hospitalization project working group. CMAJ 1998; 158: 1289–1296.

United Nations editor. Report of the Second World Assembly on Ageing; 2002; Madrid, 8–12 April 2002: United Nations, New York.

Pagliacci MC, Celani MG, Spizzichino L, Zampolini M, Aito S, Citterio A et al. Spinal cord lesion management in Italy: a 2-year survey. Spinal Cord. 2003; 41: 620–628.

Amin A, Bernard J, Najarajah R, Davies N, Gow F, Tucker S . Spinal injuries admitted to a specialist centre over a 5-year period: a study to evaluate delayed admission. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 434–437.

Bradley LJ, Kirker SG, Corteen E, Seeley HM, Pickard JD, Hutchinson PJ . Inappropriate acute neurosurgical bed occupancy and short falls in rehabilitation: implications for the National Service Framework. Br J Neurosurg 2006; 20: 36–39.

New PW, Cameron PA, Olver JH, Stoelwinder JU . Key stakeholders’ perception of barriers to admission and discharge from inpatient subacute care in Australia. MJA 2011; 195: 538–541.

New PW, Andrianopoulos N, Cameron PA, Olver JH, Stoelwinder JU . Reducing the length of stay for acute hospital patients needing admission into inpatient rehabilitation: a multicentre study of process barriers. Intern Med J 2013; 43: 1005–1011.

New PW, Jolley DJ, Cameron PA, Olver JH, Stoelwinder JU . A prospective multicentre study of barriers to discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Med J Aust 2013; 198: 104–108.

Andrews LB, Stocking C, Krizek L, Gottlieb L, Krizek C, Vargish T et al. An alternative strategy for studying adverse events in medical care. Lancet 1997; 349: 309–313.

Wolfe DL, Hsieh JTC, Curt A, Teasell RW . The SCIRE research team. Neurological and functional outcomes spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2007; 13: 11–31.

New PW, Simmonds F, Stevermuer T . Comparison of patients managed in specialised spinal rehabilitation units with those managed in non-specialised rehabilitation units. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 909–916.

Aung TS, El Masry WS . Audit of a British centre for spinal injury. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 147–150.

Scivoletto G, Morganti B, Molinari M . Early versus delayed inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation: an Italian study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 512–516.

New PW, Scivoletto G, Smith É, Townson A, Gupta A, Reeves RK et al. International survey of perceived barriers to admission and discharge from spinal cord injury rehabilitation units. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 893–897.

New PW . Reducing the process barriers in acute hospital for patients with spinal cord damage patients needing spinal rehabilitation unit admission. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 472–476.

New PW, Cameron PA, Olver JH, Stoelwinder JU . Defining barriers to discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, classifying their causes, and proposed performance indicators for rehabilitation patient flow. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 201–208.

Poulos CJ, Eagar K, Poulos RG . Managing the interface between acute care and rehabilitation - can utilisation review assist? Aust Health Rev 2007; 31: S129–S140.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SB, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Guide for the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation (including the FIM instrument), version 5.1. Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo 1997.

Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ . Generalized Additive Models. Volume 43 of Chapman & Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics & Applied Probability. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. 1990.

Schimek MGE . Smoothing and Regression: Approaches, Computation, and Application. John Wiley & Son: NY, USA. 2000.

Wood SN . Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R.. Chapman and Hall/CRC: FL, USA. 2006.

Core Team. R . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. 2013.

New PW, Rawicki HB, Bailey MJ . Nontraumatic spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Pressure ulcer patterns, prediction, and impact. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 87–93.

New PW, Cripps RA, Lee BB . A global map for non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 97–109.

New PW, Marshall R . International spinal cord injury data sets for non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 123–132.

New PW, Townson A, Scivoletto G, MWM Post, Eriks-Hoogland I, Gupta A et al. International comparison of the organisation of rehabilitation services and systems of care for patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 33–39.

Acknowledgements

The following Drs are thanked for their assistance with data collection: Irina Astrakhantseva, Puey Ling Chia, Seema Chopra, Harry Eeman, Kapil Gupta, Cristina Manu, Caroline McFarlane, Olivia Ong, Parinaz Sharifi, James Ting and especially Dr Richard Bignell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

New, P., Akram, M. Time-series analysis of the barriers for admission into a spinal rehabilitation unit. Spinal Cord 54, 126–131 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.108

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.108