Abstract

Study design:

Retrospective, open-cohort, consecutive case series.

Objective:

To describe the demographic characteristics, clinical features and outcomes in patients undergoing initial in-patient rehabilitation after an infectious cause of spinal cord myelopathy.

Setting:

Spinal Rehabilitation Unit, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Admissions between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2010.

Methods:

The following data were recorded: aetiology of spinal cord infection, risk factors, rehabilitation length of stay (LOS), level of injury (paraplegia vs tetraplegia), complications related to spinal cord damage and discharge destination. The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) and functional independence measure (FIM) were assessed at admission and at discharge.

Results:

Fifty-one patients were admitted (men=32, 62.7%) with a median age of 65 years (interquartile range (IQR) 52–72, range 22–89). On admission, 37 (73%) had paraplegic level of injury and most patients (n=46, 90%) had an incomplete grade of spinal damage. Infections were most commonly bacterial (n=47, 92%); the other causes were viral (n=3, 6%) and tuberculosis (n=1, 2%). The median LOS was 106 days (IQR 65–135). The most common complications were pain (n=47, 92%), urinary tract infection (n=27, 53%), spasticity (n=25, 49%) and pressure ulcer during acute hospital admission (n=19, 37%). By the time of discharge from rehabilitation, patients typically showed a significant change in their AIS grade of spinal damage (P<0.001). They also showed significant improvement (P<0.001) in their FIM motor score (at admission: median=27, IQR 20–34; at discharge: median=66, IQR 41–75).

Conclusion:

Most patients returned home with a good level of functioning with respect to mobility, bladder and bowel status, and their disability improved significantly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infections are a well-established but poorly studied cause of spinal cord myelopathy (SCM).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The most common pathogens that cause infections resulting in SCM are bacteria, but Mycobacterium tuberculosis and viruses are also well documented, while fungal and parasitic aetiologies are rare.1, 2, 3, 4 There are numerous risk factors associated with infections that cause SCM, including intravenous drug abuse, immune suppression (including due to diabetes, HIV infection, malnutrition, renal failure, use of steroids or alcohol), surgical procedures, sepsis and infections, and pulmonary tuberculosis.2, 4, 5 Because of the insidious onset of clinical symptoms and the nonspecificity of examination findings, there is often a delay in the diagnosis and management of spinal infections that increases their morbidity and mortality.6, 7 The prevalence of spinal epidural abscess, the most common type of infection that causes SCM in developed countries, is reported to be 2–3 per 10 000 hospital admissions.3, 4

The prevalence of infections causing SCM among patients admitted to spinal rehabilitation units that care for patients other than those with traumatic spinal cord injury varies widely, from 4% in a previous study of our patients8 up to 25% in India.9 However, there are only a few previous reports detailing specifically the functional outcomes following infectious causes of SCM.10, 11 Limitations of these previous publications include a small sample size, both originating from the USA, and not reporting longer-term outcomes. It is important that long-term functional outcomes following infectious causes of SCM are better understood, from the perspective of patients, their families and health-care providers.

The objective of this project was to describe, in a cohort of consecutive patients undergoing initial in-patient rehabilitation after a recent infectious cause of SCM, a broad range of outcomes. This includes demographic characteristics, clinical features and functional abilities, and a selection of key functional abilities at 1-year post discharge from rehabilitation.

Patients and methods

Setting, study sample and study design

The Spinal Rehabilitation Unit at Caulfield Hospital, Victoria, Australia, is a 12-bed adult in-patient unit. It is located in a public hospital and funded by the State, but patients are referred from both private and public hospitals.

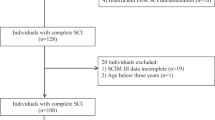

A retrospective chart review was carried out on consecutive admissions over a 16-year period, between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2010. The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition,12 was used to identify potential cases. The files were reviewed to confirm the aetiology and that patients met the inclusion criteria—only those with a new onset of SCM due to an infection were included. Patients were excluded if they were not admitted for their initial admission after the onset of SCM. Patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury who developed an infection as a complication were also excluded.

Collected data

Data on the following variables were recorded: demographic characteristics, aetiology of spinal cord infection, including the type of organism and the specific species if identified, location of infection, risk factors for infection and treatments given for spinal infection (surgery or medications), premorbid accommodation, rehabilitation length of stay (LOS), level of injury (paraplegia vs tetraplegia), common complications related to spinal cord damage, discharge destination and supports. Complications were diagnosed on the basis of clinical assessment and relevant investigations, and recorded if their occurrence necessitated treatment, either pharmacological or other. Pain and spasticity were recorded as complications if they required treatment or interfered with functioning.

Neurological impairment was assessed at admission and discharge using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS).13 The functional independence measure (FIM) is the most widely used measure of disability in rehabilitation.14 There are motor and cognitive domains,15 but in patients with SCM (including spinal cord infection) the cognitive subscale has a high ceiling effect and is of limited utility.16 Therefore, only the motor subscale was recorded within 72 h of admission and discharge. The raw FIM motor subscale scores were also transformed using a Rasch analysis conversion table to facilitate parametric analysis.17

A range of outcomes were documented at admission and discharge from in-patient rehabilitation and at the routine 12-month (range 12–16 months) postdischarge review. These included the following: mobility (walking unaided, walking ⩾100 m±gait aid, walking ⩾10 m±gait aid, wheelchair independent, and wheelchair dependent); faecal continence (faecally incontinent, colostomy, controlled faecal continence using aperients±suppositories, bowel continent without aperients); bladder control (urinary incontinent, reflex voiding+condom drainage, indwelling urethral or supra-pubic catheter, intermittent self-catheterization, and voiding on sensation); accommodation setting (home alone, home with others, hostel type, nursing home, or other).

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using Stata (version 11, Statacorp, TX, USA). Descriptive analysis was performed, including medians and interquartile range (IQR) for variables not normally distributed. The relationship between categorical variables was determined using the χ2-test, with the Fisher exact correction because of small numbers. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine the relationship between ordinal variables (e.g. AIS, mobility) and between the median FIM motor scores on admission and discharge.

P-values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Fifty-one patients with an infectious cause of spinal cord damage were admitted during the study period out of 474 patients with new onset of SCM (11.6%). The median age was 65 years (IQR 52–72, range 22–89) and the majority were men (n=32, 62.7%). The pathological organism causing infection leading to SCM was most commonly bacterial (n=47, 92%), with viral infections seen in three patients (6%, HIV in one and herpes simplex myelopathy in two) and M. tuberculosis in one case (2%) (Table 1). The location of the infection-related spinal cord damage was most often associated with epidural abscess (n=37, 73%), with osteomyelitis in 11 patients (22%), discitis in eight (16%) and myelopathy in four (8%)—multiple sites were present in six patients (four had epidural abscess, osteomyelitis and discitis and two had epidural abscess and discitis). Most patients (n=34, 67%) underwent surgery with subsequent prolonged courses of antibiotic treatment, whereas 17 (33%) had only pharmacological treatment. The pattern of onset of neurological symptoms in the acute phase prior to diagnosis of the infection was acute (<1 day) in three cases (6%), subacute (<1 week) in 19 patients (37%), prolonged (>1 week) in 17 (35%) and lengthy (>1 month) in 10 cases (20%).

The median LOS in rehabilitation was 106 days (IQR 65–135). The demographic and clinical characteristics, aetiology and infection risk factors are shown in Table 2. Eleven (22%) patients had no risk factors, 27 patients (53%) had one risk factor and 13 (25%) had two or more risk factors. Complications were very common, with only three patients (6%) not having any complication documented during their rehabilitation admission. Multiple complications were common: 15 (29%) patients had two complications and 23 (45%) patients had three or more. No patient had thrombo-embolism (prophylaxis is routine for all at-risk patients—those not ambulating more than 10 m or at less than 3 months post injury) or a pneumonia documented (Table 3). No patient died during the course of their rehabilitation admission and there were no recorded cases of late complications of infection recurrence or kyphosis, either during rehabilitation or in the subsequent 1-year follow-up period, although about a third of the study sample was lost to follow-up.

Most (n=46; 90%) patients had an incomplete grade of spinal cord damage (AIS grade B, C or D) on admission. There was significant improvement in the AIS grade of injury during the course of the patients’ rehabilitation admission (Wilcoxon signed-rank test z=−3.9, P<0.001; Table 4). Among patients who were AIS A on admission, 2/5 improved to AIS B. Among patients who were AIS B on admission, 5/10 improved to AIS C and 1/10 to AIS D. There were 10/25 AIS C patients on admission who improved to AIS D, but 1/25 worsened to AIS B.

There was significant improvement in patients’ disability during their rehabilitation. The admission motor FIM (raw median=27, IQR 20–34, range 13–63; Rasch median=34, IQR=27–38, range 0–54) increased significantly (raw FIM Wilcoxon signed-rank test Z=5.9, P<0.001; Rasch FIM Wilcoxon signed-rank test Z=−5.6, P<0.001) by discharge (raw median=66, IQR 41–75, range 13–87; Rasch median=56, IQR=43–62, range 0–77). The median FIM motor change for patients was 26 (IQR=16–42, range −21–62) and the FIM motor efficiency was a median of 0.29 (IQR=0.13–0.50).

There was significant improvement in the continence and mobility of patients during their in-patient rehabilitation. Although most patients continued to have ongoing disability at discharge, most returned to a home in the community, but with significantly fewer living alone (Table 5). In the 12 months between discharge and subsequent follow-up, there tended to be little change in continence but there were further significant improvements in mobility.

Discussion

We have found that patients with infectious causes of SCM can have significant improvement in their functional abilities during rehabilitation, particularly mobility and continence control, and that improvement can continue for up to a year post discharge for mobility.

Our results were generally in keeping with previous reports in the literature from developed countries on the infectious causes of SCM. These include the following: the increased occurrence in men between 50 and 70 years of age;4, 5, 10, 11 the range of risk factors,2, 4, 5, 10 including the common occurrence of multiple risk factors in many patients;3 the majority of infections are due to bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus Aureus;2, 3, 4, 10 most infections result from spinal epidural abscess; most patients having a paraplegic SCM and are more likely to have an incomplete lesion;5, 10, 11 and prevalence of the main complications.10 Our findings further reinforce those of others regarding patients typically having a major improvement in their AIS grade.5

Our findings differ from those previously reported for these patients10 in a number of important areas. In our sample there were no patients with thrombo-embolism or pneumonia, our FIM scores at discharge tended to be higher, our LOS in rehabilitation was much longer, as too was our proportion of patients discharged home. Some of these differences, however, may be explained by differences in health-care systems, with no limitations on the duration of in-patient rehabilitation in our unit, whereas in the USA10 limits are imposed on LOS in rehabilitation by managed care.

On comparing our results with other causes of SCM admitted at our unit, it appears that patients with an infectious aetiology tend to be of similar age, have a longer LOS in rehabilitation and have a greater disability on admission but similar disability on discharge.8, 18, 19 Patients with an infectious aetiology also appear to have some notable differences compared with those with spinal cord infarction.18 Regarding the pattern of complications, those with an infectious aetiology have a higher prevalence of spasticity and a lower prevalence of pneumonia. Furthermore, they have a much better improvement in their AIS grade, which explains their significant improvement in bladder, bowel and mobility functioning, as shown in Table 5.

We strongly agree with the recommendation made by other researcher clinicians regarding the management of infections causing SCM that this is a complex area that ideally should include a multidisciplinary team of medical practitioners, including spinal surgeons, infectious disease specialists, radiologists and rehabilitation specialists.1

We were not able to assess the potential difference in outcomes in patients with a shorter period from onset of symptoms until diagnosis because there were only three patients in our sample with symptom onset over less than 24 h.

The advantage of this study is that it is one of the largest published to date detailing the outcomes for patients with infections causing SCM. It details a significant improvement in the grade of injury that occurred during rehabilitation, which has not been reported previously, and is the largest study that reports longer-term outcomes after rehabilitation, with patient functional status and setting of residence reported at 1 year post discharge.

The generalizability of our findings to other settings is probably limited to other developed countries, as exemplified by the similarity of our findings to many previous studies highlighted above, with the exception of the LOS in rehabilitation.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective study design and relatively small sample size. However, it is important to note that this is one of the largest case series of patients with an infectious aetiology of SCM reported in the literature. It is important to emphasize that our results are probably not generalizable to other settings because the occurrence of infections as a cause of SCM globally varies between countries and regions, most notably, and not unexpectedly, between developed and developing countries.20 Differences between the aetiological pathogens (i.e. bacterial, viral, or parasitic) would be expected to be greatly influenced by geographical and environmental factors.

There are a number of important implications from this project. There is a need for a better global understanding of the infectious causes of SCM, which includes developed and developing countries, in order to more accurately describe the outcomes, particularly longer term. Ideally, this would be through prospective, multicentre studies.

We believe that studies are also required to explore the opportunities for prevention of infections causing SCM. Paralysis is reported to occur in 4–22% of cases of spinal epidural abscess and about half of the patients are initially misdiagnosed.3 The range of available health-care resources in the setting where patients reside, including prompt access to radiological imaging, neurosurgery in the case of most bacterial infections and appropriate antibiotic, antiviral or antiparasitic treatments, as indicated, would greatly influence the incidence of infectious causes of SCM as well as outcomes. Given the challenges to the early recognition of infections causing SCM6, 7 it is possible that cases of infections causing SCM, including TB,21 could be prevented by appropriate education programmes targeting health-care providers. National and global programmes are required to address the educational and resource issues that would help reduce the incidence of infections causing SCM.

In conclusion, patients with infectious causes of SCM tend to have significant improvement in their functional abilities during rehabilitation, particularly in mobility and continence control. Studies are required to explore the opportunities for the prevention of infections causing SCM.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Govender G . Spinal infections. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87-B: 1454–1458.

Grewal S, Hocking G, Wildsmith GAW . Epidural abscesses. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96: 292–302.

Darouiche RO . Spinal epidural abscess. New Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2012–2020.

Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W . Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. Q J Med 2008; 101: 1–12.

Koo DW, Townson AF, Dvorak MF, Fisher CG . Spinal epidural abscess: a 5-year case-controlled review of neurologic outcomes after rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 512–516.

Khanna RK, Malik GM, Rock JP, Rosenblum ML . Spinal epidural abscess: evaluation of factors influencing outcome. Neurosurgery 1966; 39: 958–964.

Maslen DR, Jones SR, Crislip MA, Bracis R, Dworkin RJ, Flemming JE . Spinal epidural abscess: optimizing patient care. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153: 1713–1721.

New PW . Functional outcomes and disability after nontraumatic spinal cord injury rehabilitation: results from a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 250–261.

Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Murali T . Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: epidemiology, complications, neurological and functional outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 307–311.

McKinley W, Merrell C, Meade M, Brooke K, DiNicola A . Rehabilitation outcomes after infection-related spinal cord disease: a retrospective analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 87: 275–280.

Zafonte RD, Ricker JH, Hanks RA, Wood DL, Amin A, Lombard L . Spinal epidural abscess: study of early outcome. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26: 345–351.

National Centre for Classification in Health. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) 2nd edn National Centre for Classification in Health: Sydney, Australia. 2000.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Fin Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Guide for the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation (including the FIM instrument), version 5.1. State University of New York at Buffalo: Buffalo, NY. 1997.

Heinemann AW, Linacre JM, Wright BD, Hamilton BB, Granger CV . Relationships between impairment and physical disability as measured by the Functional Independence Measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 566–573.

New PW, Simmonds F, Stevermuer T . A population-based study comparing traumatic spinal cord injury and non-traumatic spinal cord injury using a national rehabilitation database. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 397–403.

Heinemann AW, Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Wright BD, Linacre JM, Betts HB et al Rating scale analysis of functional assessment measures.: National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. Final Report 1991.

New PW, McFarlane CL . Retrospective case series of outcomes following spinal cord infarction. Euro J Neurol 2012; 19: 1207–1212.

Tan M, New PW . Retrospective study of rehabilitation outcomes following spinal cord injury due to tumour. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 127–131.

New PW, Cripps RA, Lee BB . Global maps of non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 97–109.

Moon MS . Tuberculosis of the spine: controversies and a new challenge. Spine 1997; 22: 1791–1797.

Acknowledgements

Jane Kaye, Linda Rogers and Ellen Foster from the Health Information department at Caulfield Hospital, Alfred Health, are thanked for their assistance with identifying potential cases and for the retrieval of medical files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

New, P., Astrakhantseva, I. Rehabilitation outcomes following infections causing spinal cord myelopathy. Spinal Cord 52, 444–448 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.29

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.29