Abstract

Study design:

An end-user response survey and assessments of inter-rater reliability before and after training.

Objectives:

Evaluate the spinal cord injury (SCI) application of the international classification of external cause of injury (ICECI) in a mixed group of untrained and trained coders to assess agreement, refine coding and training methodology.

Setting:

An interactive coding workshop for an international group of coders with varying previous training.

Methods:

Evaluate content validity (qualitative survey) and inter-rater reliability (kappa estimate of agreement) of the ICECI in a variety of injury scenarios presented within a computerized data-entry and training module. The results of this evaluation are compared with an earlier published gold standard.

Results:

The ICECI is a flexible data coding system that appears to work with reasonable content validity in the regions assessed with English-language coders. Training appeared to narrow the difference between the inexperienced and trained coders. This is reflected in a borderline tendency for lower kappa scores pre-training compared with an earlier examined group of expert coders (P=0.073) but no difference in kappa scores after training (P=0.67). Computer-based training on a face-to-face level with computerized data entry appears an effective tool for training coders to use the ICECI.

Conclusions:

This report shows that using electronic data-entry and training assistance, inexperienced coders using the SCI–ICECI computerized system quickly approach the levels of agreement of trained coders in related data systems. The content validity of the training data set is adequate but needs to include more cases representative for use in SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Few available spinal cord injury (SCI) data systems provide data suitable for global injury surveillance. There is an unavoidable ethnocentricity in most western database systems, which make them difficult to translate, validate and use globally. A global system needs to capture the worldwide diversity of injury mechanisms and ideally should analyze data on a number of different conceptual and resource levels.

The international classification of external cause of injury (ICECI) is part of the World Health Organisation Family of International Classifications and maps to the ninth and tenth revisions of the International Classification of Diseases. The ICECI classifies how injuries occur and was designed for use in international injury prevention.1

The ICECI has multiple axes of: intent, mechanism, object/substance, place, activity, alcohol use and drug use. Importantly, it separates the mechanism into underlying and direct categories to facilitate effective prevention strategy development (Figure 1) and consequently lends itself well to conceptual models such as the Haddon Matrix.2 It operates on three possible levels from level 1 (minimal data set) to a level 3 (full data set), allowing adjustment for different coding requirements and resources.

Different types of mechanisms are usually involved in an injury. For example, if a person trips over a carpet and hits their head on a table, tripping is the underlying mechanism (the action that starts the injury event), and the contact with the table is the direct mechanism (the action that causes the actual physical harm).1 Separating underlying from direct mechanisms enables more sophisticated prevention strategies to be designed and evaluated. The ICECI provides an adjunct (and upgrade path) to the current International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) endorsed International SCI Core Data Set3 for countries who wish to develop detailed policy relevant to SCI prevention.

The ICECI can be collected in the field with the use of a simple structured narrative of the injury (Box 1). All subsequent coding can be conducted by a trained coder at the data collection center.

This study evaluates the content validity and inter-rater reliability (agreement) of the ICECI in a variety of injury scenarios using a computerized system. It assesses whether computerized data entry is as effective as paper-based systems and evaluates the effect of training on coding of injury scenarios. The results of this evaluation are compared with an earlier published gold standard.4

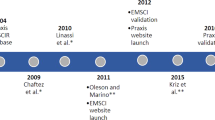

Our group takes a holistic approach toward the development of these standards including providing tools to assist spinal units to train end users and to provide a basic mechanism for electronic data entry in which these resources may not exist as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5 This project is part of the Data Sets initiative of ISCoS and the ISCoS Prevention Committee.

Method

A computer program was created (RC) to facilitate coding of the scenarios using the ICECI at level 3. Data input into the coding program used a cascading menu system that assists the coding process. Only relevant coding choices are allowed as the coder progresses through the coding structure. The program provides basic instruction as well as serves as a data repository.

Invitations were sent to interested clinicians worldwide through the ISCoS conference network to participate in testing the computerized system.

Assessment of inter-rater agreement and content validity

This consisted of two phases (Figure 2) which were compared with a reference standard.

The reference set of scenarios from Steenkamp comprised 100 scenarios many of which aimed to evaluate specific issues likely to be important to capture, difficult to code or to be characteristic of cases presenting to emergency services.4 In all, 25 scenarios were selected by RC as being relevant to SCI presentations.

Phase 1 involved seven experienced SCI clinicians from Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Korea and South Africa. These clinicians used an early version of the computerized program with minimal assistance. Each was given a searchable electronic copy of the ICECI1 (with no further instruction) and were asked to code 25 gold-standard (reference) scenarios. At the end of the coding session, qualitative feedback on the coding program was obtained through a questionnaire, which assessed categories relevant to international coding of injury scenarios (language and cultural issues, content validity, coding and computer issues). Qualitative feedback was used to modify the computer coding program subsequently used in phase 2.

Phase 2 involved seven participants from a broader cross-section of both experienced and inexperienced clinicians from Australia, Canada, China and India. The data were collected as part of a regional (ANZCoS) SCI–ICECI training workshop.6

Inter-rater agreement was assessed using unweighted kappa statistics for two unique raters. All comparisons for both phases 1 and 2 were assessed against a reference standard adapted to the project by RC, BL and JH using data from Steenkamp.4 Summary statistics for kappa scores are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. Strength of agreement was evaluated as; <0.20 poor, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 good, 0.81–1.00 very good.7 Analysis was performed using multilevel linear regression models with a random intercept to account for clustering within both events and individuals. (Stata version 10.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Phase 1 evaluation

Seven participants from six countries were involved in the qualitative evaluation (Table 1). The participants were experienced clinicians (mostly medical practitioners) rather than professional coders and had varying familiarity with health and injury coding. All participants spoke English at a professional level. Analysis of agreement to reference standard (kappa) is presented in Table 2.

Some coders showed difficulty coding using an unfamiliar injury classification and computer program without formal training. Problems were identified in the following broad areas:

Structured injury narrative

The structured injury narrative provides a coding base as well as a free-text searchable information resource. Its formulation is the key part of data collection and represents the minimal case information required to code an injury event. One respondent felt the narrative table (Box 1) was difficult to understand. All respondents felt that the computer program handled their self-entered injury events well. Linguistically, all respondents felt that local cultural issues had no effect on interpreting the narrative, however it is likely that this will have to be evaluated more widely.

Linguistic issues with the data structure (international classification of external cause of injury) and computer program

Respondents felt that it would be useful to translate the ICECI into other languages (Danish, Korean, Afrikaans and Xhosa). It is important to acknowledge that all respondents had a good command of English (although English language proficiency was not formally evaluated) and as such, the study still biases toward the English medium. The investigators felt it was important to assess how the coding was undertaken without a major intrinsic language barrier so local environmental and ethnographic factors could be analyzed. This study is intended to be repeated to assess the relative agreement of foreign language versions of the computer program and coding structure as we gain collaborating teams able to conduct such trials.

Content validity

Pilot phase respondents broadly agreed that many of the types of injury events observed in their SCI practice were not covered by the training injury narratives.

A median kappa statistic for the seven participants was calculated for each of the 25 coded scenarios (Table 2). None of the median kappa's were poor or fair (<0.4), 13 (52%) had moderate levels of agreement (0.41–0.60) and 12 (48%) had good levels of agreement (0.61–0.80).

Phase 2 evaluation

Phase 2 (A)

In this section of the workshop, untrained participants were given an introduction to the program and had access to trained coders (RC, BL) for direction. Direct answers were not given to the participants, only general coding advice. The median kappa statistics for four coding scenarios for the phase 2 (A) coders were between moderate (0.59) and very good (0.89). They did not perform quite as well as the less mixed group of coders in the reference group (Table 3). This was reflected in a borderline tendency for these reference kappas to be higher than the phase 2 (A) kappas (median (interquartile range)=0.71 (0.55, 0.89) versus 0.79 (0.69, 0.89)) respectively, P=0.073).

Phase 2 (B)

In this part of the workshop, the seven participants did not have assistance from trained coders and coded independently. By now all had familiarity with the coding software and had a basic level of training. The median kappa statistics for the four coding scenarios compared with (Steenkamp) reference group ranged between moderate (0.48) and good (0.62). The lower levels of agreement for both the phase 2 (B) and the reference group reflected the more challenging scenarios presented. The individual kappa statistics for both groups were similar (median (interquartile range)=0.54 (0.45, 0.68) versus 0.62 (0.47, 0.74)) respectively (P=0.67) (Table 4).

Discussion

The ICECI at level 3 appears to work with reasonable content validity in the regions assessed with English-language coders. Injury coding systems tend to be complex to teach and learn, and previous evaluation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention5 advocated the addition of computerized data entry. We decided that computerized training and data entry would simplify both training, and evaluation, and would provide an accessible (and free) data-entry tool for units without local information technology resources. In the following discussion, we have attempted to address the coders-specific concerns identified in the evaluation process.

Language and cultural issues

Phase 1 coders expressed concern regarding future translation of the data set and program, and we broadly agree that the training application could operate in different languages. Possibilities are to allow local language collection of the structured narrative only, or the much larger task of embarking on a full translation of the ICECI (currently a French draft is available and one in Spanish is contemplated) and/or the computer program. Allowing local language input of the structured injury narrative section is more feasible in the initial stages, although this could require a separate validation process for each language. Assessing the native-language structured narrative concurrently with a translated English narrative would enable international cross-checking and validation of a native-language narrative-based data set. Future programs could store both local and translated vignettes for future auditing purposes in non-English settings should future partners require it.

Content validity

A majority of the phase 1 respondents felt the gold standard injury narratives needed to be made more spinal injury specific. The 25 vignettes assessed in phase 1 were collated from the best validated group of responses available.4 They do provide a coding range of challenge (from easy to hard) but admittedly do not provide a typical spinal injury coding experience. For this pilot, the technical committee wanted to ensure that the gold standards were accurately coded and consequently sacrificed spinal-specific content in the process. The consortium will develop spinal injury-specific gold standards for training purposes.

Time requirements

Training, familiarity and interface changes may improve coding times. Units with fewer resources can reduce time by coding at the faster, simpler (and less rich) levels 1 or 2 or minimally can construct and store a structured injury narrative. Units using this latter modality would need to have their data retrospectively coded to ICECI to extract prevention information.

The effects of training

Training appears to narrow the difference between the inexperienced workshop group and better-trained (Steenkamp) reference group. This is reflected in a borderline tendency (P=0.073) for the reference group kappa to be better than the untrained workshop participants but no different after the participants were trained P=0.67. Computer-based training on a face-to-face basis with computerized data entry appears effective.

Ongoing contributions to international classification of external cause of injury code development

The development of the ICECI is an ongoing iterative process delegated by the World Health Organisation to the ICECI–Coordination and Maintenance Group. In September 2006, our ISCoS development group was recognized as a partner institution in the ICECI–Coordination and Maintenance Group to contribute to ICECI development and enhance its utility in coding SCI.

Conclusion

This report describes the initial international pilot of the SCI–ICECI system for collecting injury codes relevant to an international SCI prevention data set. It shows that electronic data entry and training assistance quickly approaches the levels of agreement of trained coders in related data systems. The content validity of the training data set is adequate but needs to include more SCI-representative cases, which will be undertaken by our group. The basic structured injury narrative (Box 4) can be added to existing data sets, allowing potential retroactive coding of the ICECI (although prospective data entry is likely to be more accurate). A training module for effective narrative construction is available from the ISCoS website and this is the simplest entry point to the methodology. In practice, we recommend that the ICECI coder be trained, and that the ICECI is collected in conjunction with the International SCI Core Data Set3 to provide the core of a spinal injury registry capable of reporting on the effectiveness of prevention programs. It describes the start of an iterative process, which we have opened to the wider spinal community to provide feedback on the data set and the educative and collection systems, which underpin the data system. We encourage the further international development of this system through the free release of the data tools and educational modules and will coordinate a structured open-source approach to its future development. We welcome contact and comments from prospective international partners.

The ICECI training program and SCI case registration database (evaluation version) reside on the ISCoS website at http://www.iscos.org.uk (International Standards/Data sets section).

References

ICECI Coordination Maintenance Group. International classification of external causes of injuries (ICECI) version 1.2. Consumer Safety Institute: Amsterdam and AIHW National Injury Surveillance Unit: Adelaide, Australia, 2004.

Barnett DJ, Balicer RD, Blodgett D, Fews AL, Parker CL, Links JM . The application of the Haddon matrix to public health readiness and response planning. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 561–566.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T et al. International spinal cord injury core data set. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 535–540.

Steenkamp M, Harrison J . ICECI: Case Scenario Testing: http://www.nisu.flinders.edu.au/pubs/reports/2001/iceci_injcat32.pdf4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, 2000.

Annest LJ, Pogostin CL . CDC's Short Version of the ICECI International Classification of External Causes of Injury A Pilot Test Report to the World Health Organization Collaborating Centers. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 2000.

Cripps R, Lee BB, Long D, Iedema R . ICECI Coding Workshop., ANZCoS Annual Meeting, Sydney, Australia 2008.

Altman DG . Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Hall: London, 1991.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 was drawn by Carla F Cripps.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, B., Cripps, R., Woodman, R. et al. Development of an international spinal injury prevention module: application of the international classification of external cause of injury to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 48, 498–503 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.168

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.168

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

International classification of external causes of injury: a study on its content coverage

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2021)

-

Relevance of the international spinal cord injury basic data sets to youth: an Inter-Professional review with recommendations

Spinal Cord (2017)

-

The global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: update 2011, global incidence rate

Spinal Cord (2014)

-

Estimating the global incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2014)

-

International Spinal Cord Injury Quality of Life Basic Data Set

Spinal Cord (2012)