Key Points

-

Escherichia coli O157 is one of the most important causes of bloody diarrhoea and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), especially in children and the elderly, and is therefore a zoonosis of substantial public health concern.

-

The incidence of E. coli O157 infection in Scotland is consistently one of the highest in the world.

-

The epidemiology of E. coli O157 could be largely driven by a small number of colonized cattle — its main reservoir — that for a period shed large numbers of bacteria (>104 CFU per gram of faeces), and are therefore called super-shedders.

-

We currently have only a limited understanding of both the nature and the determinants of super-shedding. However, super-shedding has been observed to be associated with colonization at the terminal rectum and it may be also more probable with certain pathogen phage types.

-

Super-shedding has important consequences for the epidemiology of E. coli O157 in cattle and for the risk of human infection, particularly through environmental exposure.

-

Super-shedding may be important in other bacterial and viral infections. If so, this will have profound implications for our understanding of the epidemiology and control of many infectious diseases. For E. coli O157 in cattle, this could potentially lead to a reduction in the risk of human infections.

Abstract

Cattle that excrete more Escherichia coli O157 than others are known as super-shedders. Super-shedding has important consequences for the epidemiology of E. coli O157 in cattle — its main reservoir — and for the risk of human infection, particularly owing to environmental exposure. Ultimately, control measures targeted at super-shedders may prove to be highly effective. We currently have only a limited understanding of both the nature and the determinants of super-shedding. However, super-shedding has been observed to be associated with colonization at the terminal rectum and might also occur more often with certain pathogen phage types. More generally, epidemiological evidence suggests that super-shedding might be important in other bacterial and viral infections.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Karmali, M. A. Infection by shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. An overview. Mol. Biotechnol. 26, 117–122 (2004).

Griffin, P. M. & Tauxe, R. V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli and the associated haemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol. Rev. 30, 60–98 (1991).

Caprioli, A., Morabito, S., Brugère, H. & Oswald, E. Enterohaemorragic Escherichia coli: emerging issues on virulence and modes of transmission. Vet. Res. 36, 289–311 (2005).

[No authors listed]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ongoing multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 infections associated with consumption of fresh spinach — United States, September 2006. MMWR 55, 1045–1046 (2006).

Mead, P. S. & Griffin, P. M. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lancet 352, 1207–1212 (1998).

Sakuma, M., Urashima, M. & Okabe, N. Verocytotoxin producing Escherichia coli, Japan, 1999–2004. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 323–325 (2006).

Pollock, K. G. J., Beattie, T. J., Reynolds, B. & Stewart, A. Clinical management of children with suspected or confirmed E. coli O157 infection. Scott. Med. J. 52, 5–7 (2007).

Armstrong, G. L., Hollingsworth, J. & Morris, J. G. Emerging food pathogens: Escherichia coli O157:H7 as a model entry of a new pathogen into the food supply of the developed world. Epidemiol. Rev. 18, 29–51 (1996).

Michel, P. et al. Temporal and geographic distributions of reported cases of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in Ontario. Epidemiol. Infect. 122, 193–200 (1999).

Valcour, J. E., Michel, P., McEwen, S. A. & Wilson, J. B. Associations between indicators of livestock farming intensity and incidence of human shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 252–257 (2002).

Innocent, G. T. et al. Spatial and temporal epidemiology of sporadic human cases of Escherichia coli O157 in Scotland 1996–1999. Epidemiol. Infect. 153, 1033–1041 (2005).

Gunn, G. J. et al. An investigation of factors associated with the prevalence of verocytotoxin producing Escherichia coli O157 shedding Scottish beef cattle. Vet. J. 174, 554–564 (2007).

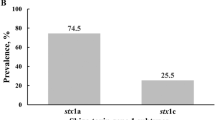

Chase-Topping, M. E. et al. Risk factors for the presence of high-level shedders of Escherichia coli O157 on Scottish farms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1594–1603 (2007). The first study to examine risk factors for super-shedders on farms. The authors highlighted an association between PT 21/28 and super-shedders.

Matthews, L. et al. Heterogeneous shedding of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle and its implications for control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 547–552 (2006).

Omisakin, F., MacRae, M., Ogden, I. D. & Strachan N. J. C. Concentration and prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle faeces at slaughter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 2444–2447 (2003).

Naylor, S. W. et al. Lymphoid follicle-dense mucosa at the terminal rectum is the principal site of colonisation of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the bovine host. Infect. Immun. 71, 1505–1512 (2003). The first study to report the terminal rectum as the site of colonization of E. coli O157 in the gut.

Low, J. C. et al. Rectal carriage of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in slaughtered cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 98–107 (2005). This study found an association between rectal carriage and a high number of E. coli O157-shedding bacteria.

Lim, J. Y. et al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization at the rectoanal junction of long duration culture positive cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1380–1382 (2007).

Cobbold, R. N. et al. Rectoanal junction colonization of feedlot cattle by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its association with supershedders and excretion dynamics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1563–1568 (2007).

Davis, M. A. et al. Comparison of cultures from rectoanal-junction mucosal swabs and feces for detection of Escherichia coli O157 in dairy herds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3766–3770 (2006).

Fox, J. T., Shi, X. & Nagaraja, T. G. Escherichia coli O157 in the rectoanal mucosal region of cattle. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 5, 69–77 (2008).

Ziebell, K. et al. Genotypic characterization and prevalence of virulence factors among Canadian Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4314–4323 (2008).

Hancock, D. D. et al. Multiple sources of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlots and dairy farms in the northwestern United States. Prev. Vet. Med. 35, 11–19 (1998).

Ogden, I. D., MacRae, M. & Strachan, N. J. C. Concentration and prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in sheep faeces at pasture in Scotland. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98, 646–651 (2005).

Berg, J. et al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 excretion by commercial feedlot cattle fed either barley- or corn-based finishing diets. J. Food Protect. 67, 666–671 (2004).

Matthews, L. et al. Super-shedding cattle and the transmission dynamics of Escherichia coli O157. Epidemiol. Infect. 134, 131–142 (2006). Together with Reference 14, this study provides mathematical evidence for super-shedders that could explain the prevalence of E. coli on Scottish farms. These references also highlight how targeting super-shedders could reduce the incidence of E. coli O157 on farms.

Vali, L. et al. Comparison of diversities of Escherichia coli O157 shed from a cohort of spring-born beef calves at pasture and in housing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 1648–1652 (2005).

Halliday, J. E. B. et al. Herd-level factors associated with the presence of Phage type 21/28 E. coli O157 on Scottish farms. BMC Microbiol. 6, 99 (2006).

Besser, T. E., Richards, B. L., Rice, D. H. & Hancock, D. D. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection of calves: infectious dose and direct contact transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 127, 555–560 (2001).

Wetzel, A. N. & LeJeune, J. T. Clonal dissemination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 subtypes among dairy farms in northeast Ohio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2621–2626 (2006).

Vali, L. et al. High-level genotypic variation and antibiotic sensitivity among Escherichia coli O157 strains isolated from two Scottish beef cattle farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5947–5954 (2004).

Renter, D. G., Sargeant, J. M. & Hungerford, L. L. Distribution of Escherichia coli O157:H7 within and among cattle operations in pasture-based agricultural areas. Am. J. Vet. Res. 65, 1367–1376 (2004).

Davis, M. A. et al. Correlation between geographic distance and genetic similarity in an international collection of bovine faecal Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates. Epidemiol. Infect. 131, 923–930 (2003).

Sargeant, J. M., Shi, X., Sanderson, M. W., Renter, D. G. & Nagaraja, T. G. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns of Escherichia coli O157 isolates from Kansas feedlots. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3, 251–258 (2006).

Hancock, D. D. et al. The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy and beef cattle in Washington State. Epidemiol. Infect. 113, 199–207 (1994).

Wilson, J. B. et al. Risk factors for bovine infection with verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Ontario. Prev. Vet. Med. 16, 159–170 (1993).

Nielsen, E. M., Tegtmeier, C., Andersen, H. J., Gronbaek, C. & Andersen, J. S. Influence of age, sex and herd characteristics on the occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in Danish farms. Vet. Microbiol. 88, 245–257 (2002).

Schouten, J. M. et al. Risk factor analysis of verocytotoxin producing Escherichia coli O157 on Dutch dairy farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 64, 49–61 (2004).

Lui, W.-C. et al. Metapopulation dynamics of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle: an explanatory model. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 917–924 (2007).

Strachan, N. J. C., Dunn, G. M., Locking, M. E., Reid, T. M. S. & Ogden, I. D. Escherichia coli O157: burger bug or environmental pathogen. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 112, 129–137 (2006).

Locking, M. E. et al. Risk factors for sporadic cases of Escherichia coli O157 infection: the importance of contact with animal excreta. Epidemiol. Infect. 127, 215–220 (2001).

O'Brien, S. J., Adak, G. K. & Gilham, C. Contact with farming environment as a major risk factor for shiga toxin (verocytotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli O157 infection in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 1049–1051 (2001).

Willshaw, G. A., Evans, J., Cheasty, T., Cummins, A. & Pritchard, G. C. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection and private farm visits. Vet. Rec. 153, 365–366 (2003).

Ogden, I. D. et al. Long term survival of Escherichia coli O157 on pasture following an outbreak associated with sheep at a scout camp. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 34, 100–104 (2002).

Cassin, M. H., Lammerding, A. M., Ross, W. & McColl, R. S. Quantitative risk assessment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ground beef hamburgers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 41, 21–44 (1998).

Strachan, N. J. C., Fenlon, D. R. & Ogden, I. D. Modelling the vector pathway and infection of humans in an environmental outbreak of Escherichia coli O157. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203, 69–73 (2001).

Haus-Cheymol, R. et al. Association between indicators of cattle density and incidence of paediatric haemolytic–uraemic syndrome (HUS) in children under 15 years of age in France between 1996 and 2001: an ecological study. Epidemiol. Infect. 134, 712–718 (2006).

Mora, A. et al. Phage types and genotypes of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates from humans and animals in Spain: identification and characterization of two predominating phage types (PT2 and PT8). J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 4007–4015 (2004).

Lahti, E. et al. Use of phenotyping and genotyping to verify transmission of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from dairy farms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21, 189–195 (2002).

Lynn, R. M. et al. Childhood haemolytic uremic syndrome, United Kingdom and Ireland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 590–596 (2005).

Callaway, T. R. et al. What are we doing about Escherichia coli O157 in cattle? J. Anim. Sci. 82, E93–E99 (2004).

Naylor, S. W. et al. Impact of the direct application of therapeutic agents to the terminal recta of experimentally colonised calves on Escherichia coli O157:H7 shedding. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1493–1500 (2007).

Potter, A. A. et al. Decreased shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by cattle following vaccination with type III secreted proteins. Vaccine 22, 362–369 (2004).

Mitchell, R. M. et al. Simulation modelling to evaluate the persistence of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) on commercial dairy farms in the United States. Prev. Vet. Med. 83, 360–380 (2008).

Lawley, T. D. et al. Host transmission of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is controlled by virulence factors and indigeneous intestinal microbiota. Infect. Immun. 76, 403–416 (2008).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Schreiber, S. J., Kopp, P. E. & Getz, W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005).

Fox, J. T. et al. Associations between the presence and magnitude of Escherichia coli O157 in faeces at harvest and contamination of preintervention beef carcasses. J. Food Prot. 71, 1761–1767 (2008).

Woolhouse, M. E. J. et al. Heterogeneities in the transmission of infectious agents: implications for the design of control programs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 338–342 (1997).

Robinson, S. E., Wright, E. J., Hart, C. A., Bennett, M. & French, N. P. Intermittent and persistent shedding of Escherchia coli O157 in cohorts of naturally infected calves. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 1045–1053 (2004).

Ogden, I. D., MacRae, M. & Strachan, N. J. C. Is the prevalence and shedding concentrations of E. coli O157 in beef cattle in Scotland seasonal? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233, 297–300 (2004).

Bach, S. J., Selinger, L. J., Stanford, K. & McAllister, T. A. Effect of supplementing corn- or barley-based feedlot diets with canola oil on faecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by steers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98, 464–475 (2005).

Roe, A. J. et al. Co-ordinate single-cell expression of LEE4- and LEE5-encoded proteins of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 54, 337–352 (2004).

Dziva, F., van Diemen, P. M., Stevens, M. P., Smith, A. J. & Wallis, T. S. Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 150, 3631–3645 (2004).

Naylor, S. W. et al. E. coli O157:H7 forms attaching and effacing lesions at the terminal rectum of cattle and colonizationrequires the LEE4 operon. Microbiology 151, 2773–2781 (2005).

Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P. & Mobley, H. L. T. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2, 123–140 (2004).

Ohnishi, M. et al. Genomic diversity of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 revealed by whole genome PCR scanning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 17043–17048 (2002).

Kudva, I. T. et al. Strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7 differ primarily by insertions or deletions, not single-nucleotide polymorphisms J. Bacteriol. 184, 1873–1879 (2002).

Steele, M. et al. Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genomic regions conserved in strains with a genotype associated with human infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 22–31 (2007).

Besser, T. E. et al. Greater diversity of shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophage insertion sites among Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates from cattle than in those from humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 671–679 (2007).

Tobe, T. et al. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14941–14946 (2006).

Abe, H. et al. Global regulation by horizontally transferred regulators establishes the pathogenicity of Escherichia coli. DNA Res. 15, 25–38 (2008).

Low, A. S. et al. Cloning, expression, and characterization of fimbrial operon F9 from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 74, 2233–2244 (2006).

Spears, K. J., Roe, A. J. & Gally, D. L. A comparison of enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255, 187–202 (2006).

Turner, J., Bowers, R. G., Begon, M., Robinson, S. E. & French, N. P. A semi-stochastic model of the transmission of Escherichia coli O157 in a typical dairy herd: dynamics, sensitivity analysis and intervention/prevention strategies. J. Theor. Biol. 241, 806–822 (2006).

Turner, J., Bowers, R. G., Clancy, D., Behnke, M. C. & Christley, R. M. A network model of E. coli transmission within a typical UK dairy herd: the effect of heterogeneity and clustering on the prevalence of infection. J. Theor. Biol. 254, 45–54 (2008).

Wood, J. C., Spiers, D. C., Naylor, S. W., Gettinby, G. & McKendrick, I. J. A continuum model of the within-animal population dynamics of E. coli O157. J. Biol. Sys. 14, 425–443 (2006).

[No authors listed]. European Centre for Disease Provention and Control. Annual epidemiological report on communicable diseases in Europe 2005. [online], http://ecdc.europa.eu/pdf/ECDC_epi_report_2007.pdf (2007).

[No authors listed]. Health protection Agency, Northern Ireland addition. Gastrointestinal infections: 2005. Monthly Report 15, 2–13 (2006).

[No authors listed]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food — 10 sites, United States 2005. MMWR 55, 392–395 (2006).

Paiba, G. A. et al. Prevalence of faecal excretion of verocytotoxogenic Escherichia coli O157 in cattle in England and Wales. Vet. Rec. 153, 347–353 (2003).

Eriksson, E., Aspan, A., Gunnarsson, A. & Vågsholm, I. Prevalence of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) O157 in Swedish dairy herds. Epidemiol. Infect. 133, 349–358 (2005).

Vold, L., Klungseth, B., Kruse, H., Skjerve, E. & Wasteson, Y. Occurrence of shigatoxinogenic Escherichia coli O157 in Norwegian cattle herds. Epidemiol. Infect. 120, 21–28 (1998).

LeJeune, J. T., Hancock, D., Wasteson, Y., Skjerve, E. & Urdahl, A. M. Comparison of E. coli O157 and shiga toxin encoding genes (stx) prevalence between Ohio, USA and Norwegian dairy cattle. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 109, 19–24 (2006).

Oporto, B., Esteban, J. I., Aduriz, G., Juste, R. A. & Hurtado, A. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and non-O157 shiga toxin-producing E. coli in healthy cattle, sheep and swine herds in northern Spain. Zoonoses Public Health 55, 73–81 (2008).

Schouten, J. M. et al. Prevalence estimation and risk factors for Escherichia coli on Dutch dairy farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 64, 49–61 (2004).

Schouten, J. M., van de Giessen, A. W., Frankena, K., De Jong, M. C. M. & Graat, E. A. M. Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in Dutch poultry, pig finishing and veal herds and risk factors in Dutch veal herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 70, 1–15 (2005).

Heuvelink, A. E. et al. Occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 on Dutch dairy farms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36, 3480–3487 (1998).

Sami, M., Firouzi, R. & Shekarforoush, S. S. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on dairy farms in Shiraz, Iran by immunomagnetic separation and multiplex PCR. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 8, 319–324 (2007).

Vidovic, S. & Korber, D. R. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in Saskatchewan cattle: characterization of isolates by using random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR, antibiotic resistance profiles and pathogenicity determinants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4347–4355 (2006).

Renter, D. G. et al. Detection and determinants of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Alberta feedlot pens immediately prior to slaughter. Can. J. Vet. Res. 72, 217–227 (2008).

Elder, R. O. et al. Correlation of enterohemorragic Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in feces, hides and carcasses of beef cattle during processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2999–3003 (2000).

Murinda, S. E. et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bulk tank milk survey of dairy farms in east Tennessee. J. Food Prot. 65, 752–759 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This study was part of IPRAVE, Epidemiology and Evolution of Enterobacteriaceae Infections in Humans and Domestic Animals, funded by the Wellcome Trust. D.G. is funded by DEFRA under the Veterinary Training and Research Initiative and by LK0006. The authors thank all members of the IPRAVE consortium who are listed in Supplementary information S1 (table).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Institutions and people in the IPRAVE consortium (PDF 179 kb)

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez Genome Project

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium

FURTHER INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Glossary

- Verocytotoxin

-

A class of bacterial toxin produced by some Escherichia coli strains and Shigella species. The name is derived from the ability of the secreted protein to kill Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells in culture.

- Immunomagnetic separation

-

A laboratory tool used to enhance the sensitivity of bacterial culture techniques. Antibodies that coat paramagnetic beads bind to any Escherichia coli O157 in the test sample, thereby capturing the cells and facilitating their concentration for subsequent routine culture.

- Odds ratio

-

An odds ratio is defined as the ratio of the odds of an event occurring in one group to the odds of it occurring in another group. If the probabilities of the event in each of the groups are p (first group) and q (second group), then the odds ratio is

An odds ratio of 1 indicates that the condition or event under study is equally likely in both groups. An odds ratio that is greater than 1 indicates that the condition or event is more likely in the first group, whereas an odds ratio that is less than 1 indicates that the condition or event is less likely in the first group.

- Phage type

-

A method for discriminating bacterial strains based on their differing susceptibility to lysis by bacteriophages.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chase-Topping, M., Gally, D., Low, C. et al. Super-shedding and the link between human infection and livestock carriage of Escherichia coli O157. Nat Rev Microbiol 6, 904–912 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2029

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2029

This article is cited by

-

Tick salivary gland components dampen Kasokero virus infection and shedding in its vertebrate reservoir, the Egyptian rousette bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus)

Parasites & Vectors (2023)

-

Natural reservoir Rousettus aegyptiacus bat host model of orthonairovirus infection identifies potential zoonotic spillover mechanisms

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Socially engaged calves are more likely to be colonised by VTEC O157:H7 than individuals showing signs of poor welfare

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

The British E. coli O157 in cattle study (BECS): factors associated with the occurrence of E. coli O157 from contemporaneous cross-sectional surveys

BMC Veterinary Research (2019)

-

Enhancing genetic disease control by selecting for lower host infectivity and susceptibility

Heredity (2019)