Key Points

-

Helicobacter pylori is a human-specific pathogen that resides in the stomach. To adapt, survive and proliferate in such environment, this bacterium has elaborated a unique set of virulence factors. The study of their mode of action is unravelling novel aspects of bacterial physiology and, at the same time, of our own physiology, and of the inflammatory and immune response.

-

The continuing research has highlighted the role of the following molecules: a powerful urease; flagellar proteins; a H-gated urea transporter; several adhesins; a vacuolating toxin that causes several specific cellular alterations that seem to be functional for the survival of the bacterium; and bacterial factors that activate inflammatory cells either directly or indirectly through inducing the tissue cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines.

-

Research is being done to develop vaccines based on studies of modified or unmodified virulence factors. The hope is to be able to prevent or eradicate infection.

Abstract

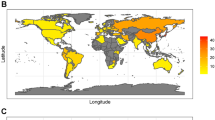

Helicobacter pylori was already present in the stomach of primitive humans as they left Africa and spread through the world. Today, it still chronically infects more than 50% of the human population, causing, in some cases, severe diseases such as peptic ulcers and stomach cancer. To succeed in these long-term associations, H. pylori has developed a unique set of virulence factors, which allow survival in a unique and hostile ecological niche — the human stomach.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Warren, J. R. & Marshall, B. J. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1, 1273–1275 (1983).The beginning of a Copernican revolution in gastroenterology, which has led to a complete change of perspective and therapeutic approach with a tremendous improvement of human health.

Achtman, M. & Suerbaum, S. (eds) Helicobacter pylori: Molecular and Cellular Biology (Horizon Scientific, Norfolk, 2001).The most updated multi-author book covering the molecular and tissue mechanisms of action of H. pylori virulence factors.

Parsonnet, J. The incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 9, suppl. 2, 45–51 (1995).

Covacci, A., Telford, J. L., Del Giudice, G., Parsonnet, J. & Rappuoli, R. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science 284, 1328–1333 (1999).

Donati, M. De Medica Historia Mirabili (Mantua, 1586).

Go, M. F. What are the host factors that place an individual at risk for Helicobacter pylori-associated disease? Gastroenterol. 113, S15–S20 (1997).

Marshall, B. J. & Langton, S. R. Urea hydrolysis in patients with Campylobacter pyloridis infection. Lancet 26, 965–966 (1986).

Hu, L. -T. & Mobley, H. L. T. Purification and N-terminal analysis of urease from Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 58, 992–998 (1990).

Labigne, A., Cussac, V. & Courcoux, P. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequences of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J. Bacteriol. 173, 1920–1931 (1991).

Jabri, E., Carr, M. B., Hausinger, R. P. & Karplus, P. A. The crystal structure of urease from Klebsiella aerogenes. Science 268, 998–1004 (1995).

Bauerfeind, P., Garner, R., Dunn, B. E. & Mobley, H. L. Synthesis and activity of Helicobacter pylori urease and catalase at low pH. Gut 40, 25–30 (1997).

Weeks, D. L., Eskandari, S., Scott, D. R. & Sachs, G. A H+-gated urea channel: the link between Helicobacter pylori urease and gastric colonization. Science 287, 482–485 (2000).A remarkable paper on how this bacterium handles the vital urea molecule.

Phadnis, S. H. et al. Surface localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and a heat shock protein homolog requires bacterial autolysis. Infect. Immun. 64, 905–912 (1996).

Dunn, B. E. et al. Localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and heat shock protein in human gastric biopsies. Infect. Immun. 65, 1181–1188 (1997).

Eaton, K. A., Brooks, C. L., Morgan, D. R. & Krakowka, S. Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect. Immun. 59, 2470–2475 (1991).

Clyne, M., Labigne, A. & Drumm, B. Helicobacter pylori requires an acidic environment to survive in the presence of urea. Infect. Immun. 63, 1669–1673 (1995).

Megraud, F., Neman-Simha, V. & Brugman, D. Further evidence of the toxic effect of ammonia produced by Helicobacter pylori urease on human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60, 1858–1863 (1992).

Suzuki, M. et al. Helicobacter pylori-associated ammonia production enhances neutrophil-dependent gastric mucosal cell injury. Am. J. Physiol. 263, G719–G725 (1992).

Sommi, P. et al. Significance of ammonia in the genesis of gastric epithelial lesions induced by Helicobacter pylori: an in vitro study with different bacterial strains and urea concentrations. Digestion 57, 299–304 (1996).

Williams, C. L., Preston, T., Hossack, M., Slater, C. & McColl, K. E. Helicobacter pylori utilizes urea for amino acid synthesis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 13, 87–94 (1996).

Harris, P. R., Mobley, H. L., Perez-Perez, G. I., Blaser, M. J. & Smith, P. D. Helicobacter pylori urease is a potent stimulus of mononuclear phagocyte activation and inflammatory cytokine production. Gastroenterol. 111, 419–425 (1996).

Ferrero, R. L., Thiberge, J. -M., Huerre, M. & Labigne, A. Recombinant antigens prepared from the urease subunits of Helicobacter pylori spp: evidence of protection in a mouse model of gastric infection. Infect. Immun. 62, 4981–4989 (1994).

Del Giudice, G., Covacci, A., Telford, J. L. Montecucco, C. & Rappuoli, R. The design of vaccines against Helicobacter pylori and their development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 523–563 (2001).A thorough and updated analysis of the current status of the effort to produce an anti H. pylori vaccine.

Josenhans, C. & Suerbaum, S. in Helicobacter pylori : Molecular and Cellular Biology (eds Achtman, M. & Suerbaum, S) 171–184 (Horizon Scientific, Norfolk, UK, 2001).

Yoshiyama, H., Nakamura, H., Kimoto, M., Okita, K. & Nakazawa, T. Chemotaxis and motility of Helicobacter pylori in a viscous environment. J. Gastroenterol. 34, suppl. 11, 18–23 (1999).

Slomiany, B. L. & Slomiany, A. Role of mucus in gastric mucosal protection. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 42, 147–161 (1991).

Lichtenberger, L. M. The hydrophobic barrier properties of gastrointestinal mucus. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 565–583 (1995).

Bhaskar, K. R. et al. Viscous fingering of HCl through gastric mucin. Nature 360, 458–461 (1992).

Slomiany, B. L., Murty, V. L., Piotrowski, J. & Slomiany, A. Gastroprotective agents in mucosal defense against Helicobacter pylori. Gen. Pharmacol. 25, 833–841 (1994).

Boren, T., Falk, P., Roth, L. A., Larson, G. & Normark, S. Attachment of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric epithelium mediated by blood group antigens. Science 262, 1892–1895 (1993).

Ilver, D. et al. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science 279, 373–377 (1998).

Evans, D. G., Karjalainen, T. K., Evans, D. J., Graham, D. Y. & Lee, C. -H. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a gene encoding an adhesion subunit protein of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 175, 674–683 (1993).

Jones, A. C. et al. A flagellar sheath protein of Helicobacter pylori is identical to HpaA, a putative N-acetylneuraminyllactose-binding hemagglutinin, but is not an adhesin for AGFS cells. J. Bacteriol. 179, 5643–5647 (1997).

Tomb, J. F. et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388, 539–547 (1997).Although H. pylori is the most recent bacterial pathogen discovered, its genome was one of the first to be sequenced. The genome sequence provides a fundamental step in the understanding of H. pylori.

Alm, R. A. et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397, 176–180 (1999).

Valkonen, K., Wadstrom, T. & Moran, A. P. Identification of the N-acetylneuraminyllactose-specific laminin binding protein. Infect. Immun. 65, 916–923 (1993).

Lingwood, C. A. et al. Receptor affinity purification of a lipid-binding adhesin from Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 61, 2474–2478 (1993)

Namavar, F., Sparrius, M., Veerman, E. C. I., Appelmelk, B. J. & Van Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C. M. Neutrophil-activating protein mediates adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to sulphated carbohydrates on high-molecular weight salivary mucin. Infect. Immun. 66, 444–447 (1997).

Odenbreit, S. et al. Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1537–1548 (1999).

Edwards, N. J. et al. Lewis X structures in the O antigen side-chain promote adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to the gastric epithelium. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1530–1539 (2000).

Smoot, D. T. et al. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to cultured human gastric epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 61, 350–355 (1993).

Segal, E. D., Falkow, S. & Tompkins, L. S. Helicobacter pylori attachment to gastric cells induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 1259–1264 (1996).

Marshall, B. J., Armstrong, J. A., McGeche, D. B. & Glancy, R. J. Attempt to fulfil Koch's postulates for pyloric Campylobacter. Med. J. Austr. 142, 436–439 (1985).A classic of medical microbiology.

Fiocca, R. et al. Epithelial cytotoxicity, immune responses, and inflammatory components of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 205, 11–21 (1994).

Dixon, M. F., Genta, R. M., Yardley, J. H. & Correa, P. Classification and grading of gastritits. The updated Sidney System. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20, 1161–1181 (1996).

Yoshida, N. et al. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. Gastroenterology 105, 1431–1440 (1993).

Evans, D. J. Jr et al. Characterization of a Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein. Infect. Immun. 63, 2213–2220 (1995).

Satin, B. et al. The neutrophil activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a protective antigen and a major virulence factor J. Exp. Med. 191, 1467–1476 (2000).An accurate characterization of the mode of activation and chemotaxis induced by HP-NAP, including the first demonstration that HP-NAP is a major antigen.

Montemurro, P. et al. HP-NAP of Helicobacter pylori alters the coagulation-fibrinolysis balance of human blood mononuclear cells by stimulating the expression of Tissue Factor and PAI-2. J. Infect. Dis. 183, 1055–1062 (2001).

Crabtree, J. E. et al. Induction of interleukin-8 secretion from gastric epithelial cells by cagA negative isogenic mutant of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Pathol. 48, 967–969 (1995).

Shimoyama, T., Everett, S. M., Dixon, M. F., Axon, A. T. R. & Crabtree, J. E. Chemokine mRNA expression in gastric mucosa is associated with Helicobacter pylori positivity and severity of gastritis. J. Clin. Pathol. 51, 765–770 (1998).

Cover, T. L. & Blaser, M. J. Purification and characterization of the vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 10570–10575 (1992).The original description of the VacA toxin.

Salama, N., Otto, G., Tompkins, L. & Falkow, S. Vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori plays a role during colonization in a mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 69, 730–736 (2001).An almost textbook example of insightful study of bacterial ecology.

McClain, M. S., Cao, P. & Cover, T. L. Amino-terminal hydrophobic region of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) mediates transmembrane protein dimerization. Infect. Immun. 69, 1181–1184 (2001).

Telford, J. L. et al. Gene structure of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin and evidence of a key role in gastric disease. J. Exp. Med. 179, 1653–1658 (1994).

Atherton, J. C. et al. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific VacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17771–17777 (1995).

Pagliaccia, C. et al. The m2 form of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin has cell-type-specific vacuolating activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10212–10217 (1998).

McClain, M. S., Schraw, W., Ricci, V., Boquet, P. & Cover, T. L. Acid activation of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) results in toxin internalization by eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 433–442 (2000).

Szabo, I. et al. Formation of anion-selective channels in the cell plasma membrane by the toxin VacA of Helicobacter pylori is required for its biological activity. EMBO J. 18, 5517–5527 (1999).

Tombola, F. et al. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin forms anion-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 76, 1401–1409 (1999).

Iwamoto, H., Czajkowsky, D. M., Cover, T. L., Szabo, G. & Shao, Z. VacA from Helicobacter pylori: a hexameric chloride channel. FEBS Lett. 450, 101–104 (1999).

Lupetti, P. et al. Oligomeric and subunit structure of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J. Cell. Biol. 133, 801–807 (1996).

de Bernard, M. et al. Low pH activates the vacuolating toxin of Helicobacter pylori, which becomes acid and pepsin resistant. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23937–23940 (1995).

Yahiro, K. et al. Activation of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin by alkaline or acid conditions increases its binding to a 250-kDa receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase beta. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36693–36699 (1999).

Cover, T. L., Hanson, P. I. &. Heuser, J. E. Acid-induced dissociation of VacA, the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin, reveals its pattern of assembly. J. Cell Biol. 138, 759–769 (1997).

Eaton, S. & Simons, K. Apical, basal, and lateral cues for epithelial polarization. Cell 82, 5–8 (1995).

Papini, E. et al. Selective increase of the permeability of polarized epithelial cell monolayers by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 813–820 (1998).

Pelicic, V. et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin associated with bacteria increases epithelial permeability independently of its vacuolating activity. Microbiology 145, 2043–2050 (1999).

de Bernard, M., Moschioni, M., Napolitani, C., Rappuoli, R. & Montecucco, C. The VacA toxin of Helicobacter pylori identifies a new intermediate filament interacting protein. EMBO J. 19, 48–56 (2000).

Hotchin, N. A., Cover, T. L. & Akhtar, N. Cell vacuolation induced by the VacA cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori is regulated by the Rac1 GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14009–14012 (1999).

Ricci, V. et al. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin accumulates within the endosomal-vacuolar compartment of cultured gastric cells and potentiates the vacuolating activity of ammonia. J. Pathol. 183, 453–459 (1997).

Molinari, M. et al. Vacuoles induced by Helicobacter pylori toxin contain both late endosomal and lysosomal markers. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25339–25344 (1997).

Papini, E. et al. The vacuolar ATPase proton pump is present on intracellular vacuoles induced by Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 44, 1–6 (1996).

Papini, E. et al. The small GTP binding protein rab7 is essential for cellular vacuolation induced by Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin. EMBO J. 16, 15–24 (1997).The demonstration that VacA induced cell vacuolization is a specific process requiring the enzymic activity of a specific Rab protein involved in the control of membrane transport at the late endosomal level.

Gunther, W., Luchow, A., Cluzeaud, F., Vandewalle, A. & Jentsch, T. ClC-5, the chloride channel mutated in Dent's disease, colocalizes with the proton pump in endocytotically active kidney cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 8075–8080 (1998).Identification of ClC-5 as the Cl− channel isoform that limits the rate of endosomal acidification by providing the counter-anion necessary for electric balance.

Tombola, F. et al. Inhibition of the vacuolating and anion activities of the VacA toxin of Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Lett. 460, 221–225 (1999).

De Bernard, M. et al. Helicobacter pylori toxin VacA induces vacuole formation by acting in the cell cytosol. Mol. Microbiol. 26, 665–674 (1997).

Ye, D., Willhite, D. C. & Blanke, S. R. Identification of the minimal intracellular vacuolating domain of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9277–9282 (1999).

Galmiche, A. et al. The N-terminal 34 kDa fragment of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin targets mitochondria and induces cytochrome c release. EMBO J. 19, 6361–6370 (2000).

Molinari, M. et al. Selective inhibition of Li-dependent antigen presentation by Helicobacter pylori toxin VacA. J. Exp. Med. 187, 135–140 (1998).

D'Elios, M. M. et al. Th1 effector specific for Helicobacter pylori in the gastric antrum of patients with peptic ulcer disease. J. Immunol. 158, 962–967.

Shirai, M., Arichi, T., Nakazawa, T. & Berzofsky, J. A. Persistent infection by Helicobacter pylori down-modulates virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response and prolongs viral infection. J. Infect. Dis. 177, 72–80 (1998).

Satin, B. et al. Vacuolating toxin of Helicobacter pylori inhibits maturation of procathepsin D and degradation of epidermal growth factor in HeLa cells through a partial neutralization of acidic intracellular compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25022–25028 (1997).

Censini, S. et al. Cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 14648–14653 (1996).The demonstration that virulent H. pylori contain a 40-kb foreign DNA (called pathogenicity island or PAI) coding for a type IV secretion system represented a milestone in the understanding of H. pylori pathogenesis and provided an explanation for the presence of the cagA gene only in a subset of strains. Also see reference 95.

Hacker, J. & Kaper, J. B. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 641–679 (2000).

Ogura, K. et al. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1601–1610 (2000).

Perez-Perez, G. I. et al. The role of CagA status in gastric and extragastric complications of Helicobacter pylori. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 50, 833–885 (1999).

Parsonnet, J. et al. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori strains. Gut 40, 297–301 (1997).

Webb, P. M., Crabtree, J. E. & Forman, D. Gastric cancer, cytotoxin-associated gene A-positive Helicobacter pylori and serum pepsinogens: an international study, the Eurogast Study Group. Gastroenterology 116, 269–276 (1999).

Christie, P. J. & Vogel, J. P. Bacterial type IV secretion: conjugation systems adapted to effector molecules to host cells. Trends Microbiol. 8, 354–360 (2000).

Asahi, M. et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein delivered into the gastric epithelial cells can be tyrosine phosphorylated. J. Exp. Med. 191, 593–602 (2000).

Segal, E. D., Cha, J., Lo, J., Falkow, S. & Tompkins, L. S. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14559–14564 (1999).

Stein, M., Rappuoli, R. & Covacci, A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Helicobacter pylori CagA after cag-driven host translocation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1263–1268 (2000).

Odenbrait, S. et al. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science 287, 1497–1500 (2000).References 91 – 94 each independently reported this unique and novel finding in bacterial pathogenesis. A bacterial protein (CagA) is introduced by a specialized secretion system (type IV secretion) into the host cell, which tyrosine phosphorylates the bacterial protein and initiates a cascade of events, which ultimately led to tissue damage and decrease.

Covacci, A. et al. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 5791–5795 (1993).

Naumann, M. et al. Activation of activator protein 1 and stress response kinases in epithelial cells colonized by Helicobacter pylori encoding the cag pathogenicity island. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31655–31662 (1999).

Pomorski, T., Meyer, T. F. & Naumann, M. Helicobacter pylori-induced prostaglandin E2 synthesis involves activation of phospholipase A2 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 804–810 (2001).

Covacci, A. & Rappuoli, R. Tyrosine-phosphorylated bacterial proteins: Trojan horses for the host cells. J. Exp. Med. 191, 587–592 (2000).

Rappuoli, R. et al. Structure and mucosal adjuvanticity of cholera and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins. Immunol. Today 20, 493–500 (1999).

Ermark, T. H. et al. Immunization of mice with urease vaccine affords protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the absence of antibodies and is mediated by MHC class II–restricted responses. J. Exp. Med. 188, 2277–2288 (1998).

Solnick, J. V. & Schauer, D. B. Emergence of diverse Helicobacter species in the pathogenesis of gastric and enterohepatic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 59–97 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the authors of the many relevant papers that we could not quote owing to space limitations. We thank A. Covacci, M. de Bernard, G. Del Giudice, W. Dundon, E. Papini, J. L. Telford and M. Zoratti for many discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript, and to G. Corsi for the artwork. Work carried out in the authors' laboratories was supported by European Community grants, by the CNR–MURST 5% Project, by MURST 40% Projects on Inflammation and by the Armenise–Harvard Medical School Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Related links

Related links

DATABASE LINKS

epithelial-derived neutrophil-activating protein 78

metaphase chromosome protein 1

mitogen-activated protein kinase

FURTHER INFORMATION

The complete sequences of two strains of H. pylori (J99 and 26695)

Glossary

- GRAM-NEGATIVE BACTERIA

-

Bacteria whose cell walls do not retain a basic blue dye during the Gram-stain procedure. These cell walls are thin, consisting of a layer of lipopolysaccharide outside a peptidoglycan layer.

- ADENOCARCINOMA

-

Cancer originating from uncontrolled proliferation of epithelial cells of the ducts and acini of glandular organs.

- LYMPHOMA

-

Cancer originating from uncontrolled proliferation of lymphocytes.

- MUCUS

-

Slimy substance secreted by mucous cells of the mucosae that consists predominantly of mucins — highly glycosylated proteins of high molecular weight. The function of mucus is to protect the linings of body cavities.

- LEWIS ANTIGEN

-

A system of soluble antigens in secretions and plasma that represents one of the serologically distinguishable human blood-group substances. Lewis specificities are carried on glycosphingolipids and glycoproteins.

- PERIPLASM

-

Space between the outer and the inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria.

- NEUTROPHIL

-

A phagocytic cell of the myeloid lineage that has an important role in the inflammatory response, undergoing chemotaxis towards sites of infection or wounding.

- MYELOPEROXIDASE

-

Peroxidase from neutrophils that takes part in the bactericidal activity of these cells. The name originates from the first isolation from the blood of patients with myeloid leukaemia.

- MONOCYTE

-

Large leukocytes with a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. They derive from pluripotent stem cells and become phagocytic macrophages when they enter the tissues.

- PROINFLAMMATORY CYTOKINES

-

Secreted proteins with autocrine or paracrine action that regulate the inflammatory response. There are many types of cytokine, which elicit different cellular responses including control of cell proliferation and differentiation, regulation of immune responses and haematopoiesis.

- EPITHELIAL CELLS

-

Polarized cells that cover the outer surfaces of the body and line internal cavities or tubes (except blood vessels).

- OXYNTIC CELLS

-

Cells of the gastric mucosa that secrete hydrochloric acid.

- PERISTALSIS

-

A wave-like sequence of contraction and relaxation that passes along a tube-like structure, resulting in a net forward movement of the content.

- LECTIN

-

Agglutinins and other antibody-like proteins of nonimmune origin that bind sugars.

- ENDOTHELIAL CELLS

-

Flattened cells that grow in a single layer and line blood vessels.

- LPS

-

(Lipopolysaccharide.) Components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria that are made of a lipid, a core oligosaccharide and an O-linked sugar side chain.

- CHEMOKINE

-

A type of chemotactic cytokine that acts primarily on haematopoietic cells in acute and inflammatory processes.

- FIBRINOLYSIS

-

The proteolysis of fibrin by plasmin in blood clots.

- TISSUE FACTOR

-

A transmembrane glycoprotein that initiates blood coagulation.

- TRANS-EPITHELIAL RESISTANCE

-

Electric resistance across epithelial sheets, measured across the apical–basolateral axis of the cell.

- TIGHT JUNCTION

-

A belt-like region of adhesion between adjacent epithelial or endothelial cells. Tight junctions regulate paracellular flux, and contribute to the maintenance of cell polarity by stopping molecules from diffusing within the plane of the membrane.

- APICAL SURFACE

-

Surface of an epithelial or endothelial cell that faces the lumen of a cavity or tube, or the outside of the organism.

- ANTIGEN-PRESENTING CELLS

-

Cells specialized in the generation of epitopes that are presented through major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) to T lymphocytes.

- CD4+ T CELLS

-

T helper cells, which collaborate with antigen-presenting cells in the initiation of an immune response.

- CD8+ CYTOTOXIC TCELLS

-

T cytotoxic cells, which are directly responsible for killing cells that present peptides through MHC I.

- TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENTS

-

Also called transposons. Specific DNA sequences that are transferred as a unit from one replicated DNA sequence to another.

- HORIZONTAL TRANSFER

-

Transfer of DNA sequences from one bacterium to another.

- COMMENSAL

-

Either of two species that live in close association with benefit to one partner but with little or no effect on the other partner.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montecucco, C., Rappuoli, R. Living dangerously: how Helicobacter pylori survives in the human stomach. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2, 457–466 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/35073084

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/35073084

This article is cited by

-

Native microbiome dominates over host factors in shaping the probiotic genetic evolution in the gut

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2023)

-

Design and synthesis of novel nitrothiazolacetamide conjugated to different thioquinazolinone derivatives as anti-urease agents

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Nonlinear machine learning pattern recognition and bacteria-metabolite multilayer network analysis of perturbed gastric microbiome

Nature Communications (2021)

-

In vivo activation of pH-responsive oxidase-like graphitic nanozymes for selective killing of Helicobacter pylori

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis pathway in host genome is associated with Helicobacter pylori infection

Scientific Reports (2021)