Abstract

Vaccination is the only type of medical intervention that has eliminated a disease successfully. However, both in countries with high immunization rates and in countries that are too impoverished to protect their citizens, many dilemmas and controversies surround immunization. This article describes some of the ethical issues involved, and presents some challenges and concepts for the global community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Vaccines stand out as being among the most efficacious and cost-effective of global medical interventions1 (Box 1). Vaccines have saved millions of lives, prevented significant morbidity and suffering, and even eradicated a disease. This last accomplishment, the eradication of smallpox, highlights what can be achieved by vaccination. However, unfortunately, the inequalities in the distribution and use of vaccines are also striking. If vaccines can be deployed so successfully worldwide that a disease can be eliminated, why do millions of children still die each year from other vaccine-preventable diseases? From ethical and humanitarian perspectives, this should be unacceptable. However, despite the medical evidence of the benefits of vaccines, both immunization itself as a goal, as well as the actual efforts for global immunization, are often debated and criticized. So, the ethics of whether, and how, to vaccinate all of the world's population are much more complex than it would seem at first glance. Some of these issues will be examined and a call for action raised in this article.

Current state of immunization rates

At present, in industrialized countries such as the United States, infants routinely (∼80–95% coverage) receive vaccines against diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B, varicella, pneumococcus and, often, hepatitis A. The efficacy of these vaccines and the success of routine immunizations are such that in the United States, for example, the morbidity from previously routine childhood diseases has been reduced by 90–100% since the introduction of standard immunization2 (Table 1). In developed countries, the near disappearance of these diseases from normal childhood has removed much of the fear of the illnesses that they cause. The result is that the consequences of not vaccinating against these diseases are sometimes not fully appreciated by the public.

In developing countries, one in every four children born annually will not be vaccinated3. In many of the impoverished countries in which these children reside, the concomitant lack of health care, inadequate nutrition4, higher prevalence of disease, decreased hygiene and over-crowding conspire to increase the incidence of, as well as the morbidity and mortality from, both vaccine-preventable and other infectious diseases. Six children die every minute as a result of infectious diseases that could be prevented by existing vaccines, and for measles alone, nearly one million children die each year3. So, each day, 4,000–8,000 people3, mainly children, die from vaccine-preventable diseases (Table 2).

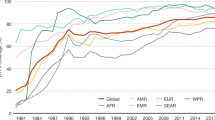

Various efforts to increase global immunization rates have protected many children successfully. For example, in 1974, before the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) was established, an estimated 8 million children died each year from measles5. Since then, the EPI has targeted six diseases: tuberculosis, measles, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio (Fig. 1). By 1980, the incidence of measles had been reduced by ∼50% (Fig. 2). In that year, the World Summit for Children set a goal of 80% coverage for these six basic immunizations to be achieved by 1990. Laudably, those efforts succeeded in raising global immunization rates from less than 10% to almost 80% in that decade6, with a concomitant reduction in disease burden (for example, see Fig. 2). But, a combination of complacency, competition for health-care resources with other diseases (such as HIV) and other factors, such as an inadequate and ageing health-care infrastructure, resulted in a subsequent plateau5 or decline in average immunization rates in the developing world6. This trend is worrying because of what it represents in terms of the commitment and sustainability of immunization programmes. Maintenance of a high level of coverage for immunization is crucial — unless a certain minimum percentage of the population is immune, the benefits of herd immunity (when sufficient people are immune such that a pathogen cannot easily persist and spread in a population) will not be achieved.

As shown, the number of vaccines (y axis) that are given to children has risen steadily since 1985 in industrialized countries, but not in developing countries. DPT is a combination vaccine against three separate pathogens: diphtheria (D), pertussis (P) and tetanus (T). BCG is the Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmètte–Guerin vaccine against tuberculosis. The loss of life due to lack of infant immunization in developing countries is due to the smaller number of vaccines that are routinely used, as well as to lower immunization rates. Reproduced, with permission, from the World Health Organization6.

The global incidence of measles has declined as immunization coverage has increased. The level of immunization coverage plateaued in the 1990s, leaving a significant number of cases of measles still occurring each year. Reproduced, with permission, from the World Health Organization22.

Ethics of immunization and vaccines

The economic and human benefits of vaccination are clear for many vaccines. But, economic and political realities, along with philosophical questions, raise certain ethical issues concerning the use and distribution of vaccines7. What are the rights of individuals in deciding about vaccination versus the rights of, and risks to, society? Should different standards for the efficacy and safety of a particular vaccine be set for different populations for which the risk:benefit ratio might be different? How should priorities be set for different areas between and within countries? Which regulatory bodies have the right to make decisions at the individual or national level? Although few would argue against the responsibility of developed nations to help poorer countries and peoples to develop and use the necessary vaccines, what are the precise responsibilities of both developed and developing countries? Here, we examine several of these issues to highlight the complexities of the ethics of vaccine development and use.

Whose choice is it? During the period when polio epidemics struck terror into the hearts of the population, the public clamoured for, supported the development of (for example, The March of Dimes in the United States, a national public compaign to raise donations to fund the research and development of polio vaccines) and welcomed a vaccine against polio. The live attenuated vaccine made possible a global mass-immunization campaign; on a single day of the various National Immunization Days, 83–147 million children were immunized8,6. Now, at a time when wild-type polio has been eliminated from the Western Hemisphere and nearly eradicated globally, the only cases of polio in the Western Hemisphere are caused by reversion mutants of the live-attenuated vaccine strain of the virus. For society as a whole, the total elimination of polio seems the obvious and correct path. But, as the probability of an individual being exposed to the virus decreases, and as the devastation of the historic polio epidemics fades in our memories, the rare cases of disease due to reversion of the vaccine itself become more prominent. The benefit of immunization for any given individual decreases (due to a lower probability of contracting the disease), whereas the perception of risk might increase9. So, what is best for the individual might be seen as potentially different from what will benefit society as a whole. However, it has only been through the participation of hundreds of millions of individuals in vaccination programmmes that unimmunized individuals have the luxury of an altered risk:benefit ratio. Interestingly, in 1980, the year that smallpox was officially declared to be eradicated, prominent individuals in the international health-planning community were critical of the smallpox campaign. They felt that the approach of 'top–down' (mandated and orchestrated by global bodies) programmes was wrong and contrary to more-localized, primary health care10,11. Even this pre-eminent example of the beneficial power of immunization was not without controversy.

In the same manner, other vaccines have become victims of their own success. As diseases disappear from the general population after successful vaccination campaigns, the real risk of an individual contracting the disease decreases and the perception of the seriousness of the disease, even if contracted, is reduced. Concomitantly, concerns about the real or imagined adverse effects of the vaccines increase. As a result, individuals might disagree with government mandates for population-wide vaccination. For example, before the introduction of a vaccine against pertussis, there were approximately 2 million cases annually in the United States. In Great Britain, in the mid-1970s, some adverse reactions to the vaccine were widely publicized, and immunization rates declined from 80–90% to 30%. As a consequence, the population was vulnerable to two subsequent severe outbreaks of whooping cough, which resulted in more than 120,000 recorded instances of disease, hundreds of cases of serious complications and 28 deaths12. More recently, heightened fears of the perceived adverse effects of other vaccines (such as measles and hepatitis B), even if unproven, have had an impact on immunization rates and the incidence of disease6,13,14,15. A greater awareness of the consequences of failure to vaccinate, through better education, might be the best tool to combat this problem16.

Poverty and priorities. In wealthier countries, the ethical issues that surround vaccination tend to focus on the rights of individuals versus government or society. In poorer countries, the fundamental issue is the lack of access to basic necessities for health, such as adequate nutrition, clean water, medicines or vaccines. Although poverty is clearly the main cause of these deficiencies, other factors contribute, such as the low priority given to health and preventive measures, the disenfranchisement and lack of political and economic power of the people most affected (children and women), corruption and regional warfare.

In the year 2000, only 10% of global medical-research funds were directed towards the 90% of diseases that affect the world's poorest people6. It would seem obvious from the economic benefits that prevention of disease (and health in general) should be a priority for poor countries. It would seem equally obvious that helping to ensure such health should be a high priority for wealthy nations, even if simply to protect their own populations. Not only can newly emerging diseases spread rapidly across the globe, but pathogens eliminated from one population can be 're-imported' (or new strains introduced) by travellers or immigrants17.

At present, only about 1% of contributions to overseas development are directed towards immunizations6. The hurdle is not simply the purchase price or availability of vaccines, but for many poor countries, there is a lack of infrastructure for health care in general, and vaccine delivery specifically. The needs are so great and so widespread, both geographically and technologically, that assigning priority is difficult. This prioritization is considered by some to be an ethical issue, but in reality, it might be simply that the pie is not sufficiently large, rather than that the pie should be sliced differently. The trade-off of protecting children now from disease versus an emphasis on the development of new vaccines to protect children in the future is not a debate that can be resolved even by Solomonic wisdom. Neither trade-off is ethically defensible, and the world should, instead, work constructively to increase the resources devoted to health, nutrition, prevention and specifically immunization, to make vaccines available to all people as required. But, how is this to be accomplished?

'Trickle-down' or simultaneous introduction. A marked effort is required to introduce vaccines into all necessary areas of the globe in a more timely fashion. The average time lag between licensing of a new vaccine for industrialized countries and its use in less developed countries is 10–20 years6. There are many reasons for this, including the lack of manufacturing capability for vaccines that require new technology in their production, return on investment and the cost of manufacturing newer technology-based vaccines. For example, when the recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine was first introduced, there was not sufficient capacity worldwide for its production. Moreover, the cost of manufacturing such a 'high-tech' vaccine put it beyond the reach of the existing purchasing programmes at the time. Although the technology that supports recombinant protein vaccines is now available worldwide, it took time and effort to develop that capacity, even in developed countries.

People are created equal, but different

The simultaneous introduction of vaccines into developed and developing countries is an important goal. However, this is easier said than done. In addition to the issues of availability and economics, it cannot be assumed that disease burden, strain prevalence, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness (how well a vaccine works in clinical trials and real-world settings, respectively), immunization schedules or risk:benefit ratio will be standard or will justify the use of a vaccine in all areas. Differences in genotype and health status of individuals could affect how their immune system responds to a given immune stimulus. Environmental influences on the immune system (for example, indigenous parasitic infections that affect the predominant cytokine-secretion profile of helper T cells, or bacterial infections that facilitate or hinder immunity against closely related pathogens) might affect the immunological outcome of a particular type of vaccine.

Just as a vaccine that works in one population might not be as effective in another population, so might adverse effects of a vaccine be specific to one population. Hence, a vaccine company might be reluctant to simultaneously test a vaccine in two populations, for fear that an adverse effect in one population (due to genetic, nutritional or other health factors, or limitations of the infrastructure for vaccine delivery) would halt the development of a vaccine that could be both useful and commercially viable in another population. More importantly, the higher background rates of morbidity and mortality in certain developing countries might cause problems when presenting vaccines for licensure in more developed countries.

A counter-example to illustrate why vaccines might need to be tested simultaneously in developed and developing countries is provided by a rotavirus vaccine. Rotavirus is a major cause of diarrhoea in infants. In the United States, 20 children die each year from rotavirus infection, and worldwide, the virus kills 600,000 children under the age of five annually18. In 1998, a new rotavirus vaccine was licensed in the United States. But by 1999, reports emerged from American clinics of the occurrence, after immunization, of a small number of cases of intestinal intussusception — a 'telescoping' of the small intestine that often requires emergency surgery18. The number of cases was small, and the aetiological link has been debated, but the vaccine was withdrawn from the market. Clinical trials that were testing the vaccine in developing countries were stopped. So, we do not yet know whether the vaccine would have been effective or caused side effects in children from developing countries, for whom the risk:benefit ratio might well be quite different. More than half a million children continue to die each year due to rotavirus infection (although it is hoped that other rotavirus vaccines that are under development will be approved for use). The issue of how to speed up vaccine deployment for developing countries and how to develop vaccines that specifically address the needs of those countries should not be oversimplified. Different vaccines (for example, for different virus strains) might be required to prevent the same disease in different parts of the world. The needs of people in developing countries must be specifically, rapidly and directly addressed to develop appropriate vaccines. To make this happen in a timely manner, more thought and effort is required at early stages of vaccine development. But, by whom and at whose expense?

A farewell to arms

In the face of the unacceptable and gaping inequalities in access to vaccines, the temptation has been to 'point the finger' at various countries or segments of society. A chief target for many of these denouncements has been large vaccine manufacturers, as well as the people and governments of their home countries. It has been easy to stir up indignation, although a thoughtful evaluation of the real contributions, roles and responsibilities of all parties has been more productive (Box 2). The cries for companies to lower the prices of their vaccines has reinforced the unwarranted notion that vaccines should be inexpensive — an idea that perpetuates the vicious cycle of the low valuation of health care, prevention and children's lives. Obviously, low cost might be an important means of increasing access to vaccines, but the fundamental problem is the low priority given to children, health and prevention.

Most vaccines that are in use today were developed fully and are manufactured by industry, rather than the public sector. Commercial companies have responsibilities to their shareholders and are driven by profits. But, it is these profits that have enabled the companies to take the huge economic risks that are required for the long process of discovery, research and development of vaccines. If all economic incentive were removed, or made too small, even fewer companies would bother to make vaccines19, and, instead, would concentrate solely on therapeutic agents, because people will pay more for drugs that treat, rather than prevent, disease.

So, companies should not be expected to be philanthropic, although they should be expected to be generous global citizens. Indeed, industry-driven scientific and technological advances have had an important impact on improving global health. Combination vaccines — whereby several vaccines can be given with a single injection — were developed in part for the market advantage that they would provide but have been an important tool for increasing global vaccination rates. In addition, industry and academia are both contributing to the continuing development of vaccines that do not require refrigeration or needles and can be given orally or nasally — a true 'farewell to arms'.

In most walks of life, philanthropy usually comes as a consequence of success, and the same is true for medicines. So, the profit-driven priorities of vaccine companies are not unethical per se; rather, they are not driven primarily by ethical concerns, and the challenge is how to increase the efforts of industry that are directed at improving health on a global basis. The fact that only 1% of pharmaceuticals that reached the market-place between 1975 and 1997 were approved specifically for diseases of the developing world6 shows that, as a society, we need to re-evaluate our priorities and our paradigms, not that the economic model of financial incentive driving technical advances is wrong.

The challenge

We should challenge each economic sector, population and government to appropriately fulfil its responsibility to fellow humans or its own citizens; in other words, they should treat all of the world's children as their own, rather than denouncing particular groups as causing these inequities. Further support must be given rapidly to those whose efforts will result in vaccines that are better tailored for developing countries, both in terms of the disease focus and the development of technologies that will facilitate vaccine access and sustainability. New paradigms, including novel public–private partnerships (Box 2) and alliances that are designed to engage local governments and manufacturers at early stages of research and development, are required. In this way, each group can contribute what they do best to the common goals of improving access to existing vaccines, developing new vaccines and technologies for existing diseases (such as HIV and malaria), and ensuring that increases in immunization rates are sustainable. Perhaps most difficult of all will be to change the mindset of people all over the globe. We need to place a higher priority on health and disease prevention, and above all, to value the lives of all people, no matter where they live — even if they are impoverished and powerless.

References

Ten great public health achievements — United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 48, 241–243 (1999).

Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children — United States, 1990–1998. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 48, 243–248 (1999).

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations. Global immunization challenges [online], 〈http://www.vaccinealliance.org/reference/globalimmchallenges.html〉

Rice, A. L., Sacco, L., Hyder, A., & Black, R. E. Malnutrition as an underlying cause of childhood deaths associated with infectious diseases in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 1207–1221 (2000).

Hinman, A. Eradication of vaccine-preventable diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 20, 211–229 (1999).

World Health Organization. State of the World's Vaccine and Immunizations (in the press)

Feudtner, C. & Marcuse, E. K. Ethics and immunization policy: promoting dialogue to sustain consensus. Pediatrics 107, 1158–1164 (2001).

Foege, W. in New Generation Vaccines (eds Levin, M., Woodrow, G., Kaper, J. & Cobon, G.) 97 (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1997).

Wilson, C. B. & Marcuse, E. K. Vaccine safety–vaccine benefits: science and the public's percepion. Nature Rev Immunol 1, 160–165 (2001).

Henderson, D. A. Eradication: lessons from the past. Bull. World Health Organ. 76, 17–21 (1998).

Henderson, D. A. Primary health care as a practical means for measles control. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5, 606–607 (1983).

Ada, G. in New Generation Vaccines 2nd edn (eds Levine, M. et al.) 13–24 (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1997).

Wakefield, A. et al. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 351, 637–641 (1998).

Birmingham, K. UK immunization highs and lows. Nature Med. 7, 135 (2001).

Duffell, E. Attitudes of parents towards measles and immunisation after a measles outbreak in an anthroposophical community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 55, 685–686 (2001).

Bazin, H. The ethics of vaccine usage in society: lessons from the past. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 505–510 (2001).

Hinman, A. Eradication of vaccine-preventable diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 20, 211–229 (1999).

Instussusception among recipients of rotavirus vaccine— United States, 1998–1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 48, 577–581 (1999).

Wilde, H. What are today's orphaned vaccines? Clin. Infect. Dis. 33, 648–650 (2001).

Jimenez, J. Vaccines — a wonderful tool for equity in health. Vaccine 19, 2201–2205 (2001).

Vandermissen, W. WHO expectation and industry goals. Vaccine 19, 1611–1615 (2001).

Department of Vaccines and Biologicals. WHO Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Monitoring System 2001 Global Summary (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2001) 〈http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents/GlobalSummary/GlobalSummary.pdf〉

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank C. Wiley and, in particular, R. Ingrum for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Related links

Related links

FURTHER READING

Public–private partnerships

Global Polio Eradication Initiative

Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative

The Global Alliance for TB Drug Development

Governmental and professional groups

Global Alliance for Vaccines & Immunization

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ulmer, J., Liu, M. Ethical issues for vaccines and immunization. Nat Rev Immunol 2, 291–296 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri780

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nri780

This article is cited by

-

Three Harm-Based Arguments for a Moral Obligation to Vaccinate

Health Care Analysis (2022)

-

A novel vehicle routing problem for vaccine distribution using SIR epidemic model

OR Spectrum (2021)

-

Modeling Optimal Age-Specific Vaccination Strategies Against Pandemic Influenza

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2012)

-

Präventionsmaßnahmen im Spannungsfeld zwischen individueller Autonomie und allgemeinem Wohl

Ethik in der Medizin (2010)

-

Impfprogramme im Spannungsfeld zwischen individueller Autonomie und allgemeinem Wohl

Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (2008)