Key Points

-

Over the past two decades, phylogenetic analyses of mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome polymorphisms supported a simple model of human origins, called the single origin hypothesis.

-

The single origin model proposes that anatomically modern humans trace their ancestry to a single small population that lived in Africa, and that, following a speciation bottleneck, the population expanded and completely replaced archaic forms of humans.

-

More sophisticated methods of analysis, based on the coalescent approach, are being applied to a plethora of new genomic sequence data.

-

These new analyses of multilocus sequence data show a large variance in the shape and depth of genealogies for X-chromosomal and autosomal loci, and present a more complex picture of human demographic history.

-

Non-African populations have reduced diversity and fewer rare polymorphisms than African populations, suggesting a history of bottlenecks. By contrast, African populations do not exhibit the predicted patterns of polymorphism after a speciation bottleneck.

-

These genome-scale patterns could be best accounted for by models that involve low levels of gene flow among archaic populations before the emergence of anatomically modern humans — that is, they imply the existence of ancestral population structure.

-

There is also growing evidence that some highly divergent genetic lineages might have entered our genome through hybridization between an expanding anatomically modern human population and archaic forms of humans.

-

Further tests of the predictions of these models await more systematic surveys of DNA sequence variation in multiple human populations, along with more sophisticated methods of population genetic inference.

Abstract

Analyses of recently acquired genomic sequence data are leading to important insights into the early evolution of anatomically modern humans, as well as into the more recent demographic processes that accompanied the global radiation of Homo sapiens. Some of the new results contradict early, but still influential, conclusions that were based on analyses of gene trees from mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome sequences. In this review, we discuss the different genetic and statistical methods that are available for studying human population history, and identify the most plausible models of human evolution that can accommodate the contrasting patterns observed at different loci throughout the genome.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Day, M. H. Omo human skeletal remains. Nature 222, 1135–1138 (1969).

McDougall, I., Brown, F. H. & Fleagle, J. G. Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature 433, 733–736 (2005).

Wood, B. Hominid revelations from Chad. Nature 418, 133–135 (2002).

Anton, S. C. & Swisher, C. C. Early dispersal of Homo from Africa. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 33, 271–296 (2004).

Teshima, K. M., Coop, G. & Przeworski, M. How reliable are empirical genomic scans for selective sweeps? Genome Res. 16, 702–712 (2006).

Stringer, C. B. & Andrews, P. Genetic and fossil evidence for the origin of modern humans. Science 239, 1263–1268 (1988). An early synthesis of genetic and fossil evidence that supports the recent African origin of anatomically modern humans.

Cann, R. L., Stoneking, M. & Wilson, A. C. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature 325, 31–36 (1987). An influential paper that discusses one of the first attempts to use mtDNA data to infer the origin of anatomically modern humans.

Excoffier, L. Human demographic history: refining the recent African origin model. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 675–682 (2002).

Harpending, H. C. et al. Genetic traces of ancient demography. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1961–1967 (1998). One of the first comparisons of haploid and non-haploid sequence data in the context of explicit models that incorporate a history of bottlenecks and different ancestral effective population sizes for modern humans.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P. & Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1994).

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. & Feldman, M. W. The application of molecular genetic approaches to the study of human evolution. Nature Genet. 33, S266–S275 (2003).

Hey, J. & Machado, C. A. The study of structured populations — new hope for a difficult and divided science. Nature Rev. Genet. 4, 535–543 (2003).

Avise, J. C. et al. Intraspecific phylogeography: the mitochondrial bridge between population genetics and systematics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18, 489–522 (1987).

Vigilant, L., Stoneking, M., Harpending, H., Hawkes, K. & Wilson, A. C. African populations and the evolution of human mitochondrial DNA. Science 253, 1503–1507 (1991).

Ingman, M., Kaessmann, H., Pääbo, S. & Gyllensten, U. Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature 408, 708–713 (2000).

Hammer, M. F. et al. Out of Africa and back again: nested cladistic analysis of human Y chromosome variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 427–441 (1998).

Underhill, P. A. et al. Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations. Nature Genet. 26, 358–361 (2000).

Takahata, N., Lee, S. H. & Satta, Y. Testing multiregionality of modern human origins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 172–183 (2001).

Garrigan, D., Mobasher, Z., Severson, T., Wilder, J. A. & Hammer, M. F. Evidence for archaic Asian ancestry on the human X chromosome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 189–192 (2005).

Wilder, J. A., Mobasher, Z. & Hammer, M. F. Genetic evidence for unequal effective population sizes of human females and males. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2047–2057 (2004).

Jaruzelska, J., Zietkiewicz, E. & Labuda, D. Is selection responsible for the low level of variation in the last intron of the ZFY locus? Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1633–1640 (1999).

Harding, R. M. & McVean, G. A structured ancestral population for the evolution of modern humans. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 667–674 (2004).

Watterson, G. A. On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor. Popul. Biol. 7, 256–276 (1975).

Tajima, F. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics 105, 437–460 (1983).

Hammer, M. F. et al. Heterogeneous patterns of variation among multiple human X-linked loci: the possible role of diversity-reducing selection in non-Africans. Genetics 167, 1841–1853 (2004).

Harding, R. M. et al. Archaic African and Asian lineages in the genetic ancestry of modern humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60, 772–789 (1997). A seminal paper on the use of autosomal resequencing data to infer the history of modern human populations.

Zhao, Z. et al. Worldwide DNA sequence variation in a 10-kilobase noncoding region on human chromosome 22. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11354–11358. (2000).

Yu, N. et al. Global patterns of human DNA sequence variation in a 10-kb region on chromosome 1. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 214–222 (2001).

Fischer, A., Wiebe, V., Pääbo, S. & Przeworski, M. Evidence for a complex demographic history of chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 799–808 (2004).

Yu, N. et al. Low nucleotide diversity in chimpanzees and bonobos. Genetics 164, 1511–1518 (2003).

Kaessmann, H., Wiebe, V., Weiss, G. & Pääbo, S. Great ape DNA sequences reveal a reduced diversity and an expansion in humans. Nature Genet. 27, 155–156 (2001).

Tajima, F. The effect of change in population size on DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 597–601 (1989).

Fu, Y. X. & Li, W. H. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133, 693–709 (1993).

Fay, J. C. & Wu, C. I. A human population bottleneck can account for the discordance between patterns of mitochondrial versus nuclear DNA variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1003–1005 (1999). The first paper to recognize that differences in the effective population sizes of the haploid and autosomal compartments of the genome result in a different frequency spectrum after a population bottleneck.

Charlesworth, B., Charlesworth, D. & Barton, D. E. The effects of genetic and geographic structure on neutral variation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 34, 99–125 (2003).

Hammer, M., Blackmer, F., Garrigan, D., Nachman, M. & Wilder, J. Human population structure and its effects on sampling Y chromosome variation. Genetics 164, 1495–1509 (2003).

Ptak, S. E. & Przeworski, M. Evidence for population growth in humans is confounded by fine-scale population structure. Trends Genet. 18, 559–563 (2002).

Kingman, J. F. C. On the genealogy of a large population. J. Appl. Probab. 19A, 27–43 (1982).

Kingman, J. F. C. The coalescent. Stochastic Process Appl. 13, 235–248 (1982).

Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference in molecular population genetics. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 62, 605–655 (2000).

Beaumont, M. A. Recent developments in genetic data analysis: what can they tell us about human demographic history? Heredity 92, 365–379 (2004).

Tavare, S., Balding, D. J., Griffiths, R. C. & Donnelly, P. Inferring coalescence times from DNA sequence data. Genetics 145, 505–518 (1997). Presents for the first time the argument that the likelihood of an evolutionary model can be calculated from a statistical summary of genetic data, rather than directly from the data.

Pritchard, J. K., Seielstad, M. T., Perez-Lezaun, A. & Feldman, M. W. Population growth of human Y chromosomes: a study of Y chromosome microsatellites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1791–1798 (1999).

Voight, B. F. et al. Interrogating multiple aspects of variation in a full resequencing data set to infer human population size changes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18508–18513 (2005). A recent study of 50 non-coding resequenced loci that supports a strong genetic bottleneck as humans migrated from Africa.

Wall, J. D. & Przeworski, M. When did the human population size start increasing? Genetics 155, 1865–1874 (2000). Among the first analyses to acknowledge that there is too much variance in the genomic frequency spectrum to be compatible with any simple neutral model of population history.

Slatkin, M. & Hudson, R. R. Pairwise comparisons of mitochondrial DNA sequences in stable and exponentially growing populations. Genetics 129, 555–562 (1991).

Di Rienzo, A. & Wilson, A. C. Branching pattern in the evolutionary tree for human mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 1597–1601 (1991).

Rogers, A. R. Genetic evidence for a Pleistocene population explosion. Evolution 49, 608–615 (1995).

Hey, J. Mitochondrial and nuclear genes present conflicting portraits of human origins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14, 166–172 (1997).

Przeworski, M., Hudson, R. R. & Di Rienzo, A. Adjusting the focus on human variation. Trends Genet. 16, 296–302 (2000).

Frisse, L. et al. Gene conversion and different population histories may explain the contrast between polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium levels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 831–843 (2001).

Harpending, H. & Rogers, A. Genetic perspectives on human origins and differentiation. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1, 361–385 (2000).

Adams, A. M. & Hudson, R. R. Maximum-likelihood estimation of demographic parameters using the frequency spectrum of unlinked single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Genetics 168, 1699–1712 (2004).

Marth, G. T., Czabarka, E., Murvai, J. & Sherry, S. T. The allele frequency spectrum in genome-wide human variation data reveals signals of differential demographic history in three large world populations. Genetics 166, 351–372 (2004).

Reich, D. E. et al. Linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nature 411, 199–204 (2001).

Akey, J. M. et al. Population history and natural selection shape patterns of genetic variation in 132 genes. PLoS Biol. 2, e286 (2004).

Pluzhnikov, A., Di Rienzo, A. & Hudson, R. R. Inferences about human demography based on multilocus analyses of noncoding sequences. Genetics 161, 1209–1218 (2002).

InternationalHapMapConsortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature 437, 1299–1320 (2005).

Lonjou, C. et al. Linkage disequilibrium in human populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 6069–6074 (2003).

Wakeley, J. & Aliacar, N. Gene genealogies in a metapopulation. Genetics 159, 893–905 (2001).

Klein, R. G. The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999).

Wakeley, J., Nielsen, R., Liu-Cordero, S. N. & Ardlie, K. The discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms and inferences about human demographic history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 1332–1347 (2001).

Satta, Y. & Takahata, N. The distribution of the ancestral haplotype in finite stepping-stone models with population expansion. Mol. Ecol. 13, 877–886 (2004).

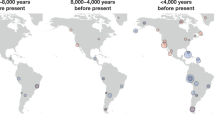

Templeton, A. R. Out of Africa again and again. Nature 416, 45–51 (2002).

Zietkiewicz, E. et al. Haplotypes in the dystrophin DNA segment point to a mosaic origin of modern human diversity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 994–1015 (2003).

Harris, E. E. & Hey, J. X chromosome evidence for ancient human histories. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3320–3324 (1999). One of the first papers to show the effects of ancient population structure on patterns of polymorphism at a locus in humans.

Garrigan, D., Mobasher, Z., Kingan, S. B., Wilder, J. A. & Hammer, M. F. Deep haplotype divergence and long-range linkage disequilibrium at Xp21.1 provide evidence that humans descend from a structured ancestral population. Genetics 170, 1849–1856 (2005). The first resequencing data set to reject the hypothesis that humans are descended from a single, randomly mating ancestral population.

Baird, D. M., Coleman, J., Rosser, Z. H. & Royle, N. J. High levels of sequence polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium at the telomere of 12q: implications for telomere biology and human evolution. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 235–250 (2000).

Barreiro, L. B. et al. The heritage of pathogen pressures and ancient demography in the human innate-immunity CD209/CD209L region. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 869–886 (2005).

Hardy, J. et al. Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens. Biochem. Soc. Trans 33, 582–585 (2005).

Stefansson, H. et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nature Genet. 37, 129–137 (2005).

Hayakawa, T., Aki, I., Varki, A., Satta, Y. & Takahata, N. Fixation of the human-specific CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase pseudogene and implications of haplotype diversity for human evolution. Genetics 172, 1139–1146 (2006).

Koda, Y. et al. Contrasting patterns of polymorphisms at the ABO-secretor gene (FUT2) and plasma α(1,3)fucosyltransferase gene (FUT6) in human populations. Genetics 158, 747–756 (2001).

Wolpoff, M. H. Paleoanthropology (McGraw-Hil, Boston, 1999).

Stringer, C. Human evolution: out of Ethiopia. Nature 423, 692–693 (2003).

Brauer, G. in The Human Revolution: Behavioural and Biological Perspectives on the Origins of Modern Humans (eds Mellars, P. & Stringer, C.) 123–154 (Edinburgh Univ. Press, Edinburgh, 1989).

Smith, F. H., Jankovic, I. & Karavanic, I. The assimilation model, human origins in Europe, and the extinction of Neanderthals. Quaternary Int. 137, 7–19 (2005).

Eswaran, V. A diffusion wave out of Africa: the mechanism of the modern human revolution? Curr. Anthropol. 43, 749–774 (2002).

Relethford, J. Genetics and the Search for Modern Human Origins (Wiley-Liss, New York, 2001).

Plagnol, V. & Wall, J. D. Possible ancestral structure in human populations. PLoS Genet. 2, e105 (2006).

Pääbo, S. The mosaic that is our genome. Nature 421, 409–412 (2003).

Wilder, J. A., Kingan, S. B., Mobasher, Z., Pilkington, M. M. & Hammer, M. F. Global patterns of human mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome structure are not influenced by higher migration rates of females versus males. Nature Genet. 36, 1122–1125 (2004).

Kitano, T., Schwarz, C., Nickel, B. & Pääbo, S. Gene diversity patterns at 10 X-chromosomal loci in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1281–1289 (2003).

Alonso, S. & Armour, J. A. A highly variable segment of human subterminal 16p reveals a history of population growth for modern humans outstide Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 864–869 (2001).

Martinez-Arias, R. et al. Sequence variability of a human pseudogene. Genome Res. 11, 1071–1085 (2001).

Rieder, M. J., Taylor, S. L., Clark, A. G. & Nickerson, D. A. Sequence variation in the human angiotensin converting enzyme. Nature Genet. 22, 59–62 (1999).

Clark, A. G. et al. Haplotype structure and population genetic inferences from nucleotide-sequence variation in human lipoprotein lipase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 595–612 (1998).

Fullerton, S. M. et al. Apolipoprotein E variation at the sequence haplotype level: implications for the origin and maintenance of a major human polymorphism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 881–900 (2000).

Bamshad, M. J. et al. A strong signature of balancing selection in the 5′ cis-regulatory region of CCR5. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10539–10544 (2002).

Wooding, S. P. et al. DNA sequence variation in a 3.7-kb noncoding sequence 5′ of the CYP1A2 gene: implications for human population history and natural selection. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 528–542 (2002).

Toomajian, C. & Kreitman, M. Sequence variation and haplotype structure at the human HFE locus. Genetics 161, 1609–1623 (2002).

Harding, R. M. et al. Evidence for variable selective pressures at MC1R. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 1351–1361 (2000).

Harris, E. E. & Hey, J. Human populations show reduced DNA sequence variation at the factor IX locus. Curr. Biol. 11, 774–778 (2001).

Alonso, S. & Armour, J. A. Compound haplotypes at Xp11.23 and human population growth in Eurasia. Ann. Hum. Genet. 68, 428–437 (2004).

Templeton, A. R. Haplotype trees and modern human origins. Yearb. Phys. Anthropol. 48, 33–59 (2005).

Patin, E. et al. Deciphering the ancient and complex evolutionary history of human arylamine N-acetyltransferase genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78, 423–436 (2006).

Vander Molen, J. et al. Population genetics of CAPN10 and GPR35: implications for the evolution of type 2 diabetes variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 548–560 (2005).

Acknowledgements

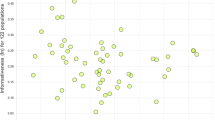

We thank A. Di Rienzo for providing Tajima's D values and the following people for providing feedback on the manuscript: M. Cox, L. Excoffier, F. Mendez, C. Stringer, J. Wilder and E. Wood. Some of the work presented here was made possible by a US National Science Foundation HOMINID grant to M.F.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Glossary

- Hominin

-

All the taxa on the human lineage after the split from the common ancestor with the chimpanzee.

- Neutral DNA polymorphism

-

Nucleotide variants that segregate in a population but have frequencies that are not influenced by natural selection.

- Demographic processes

-

Changes in population size, distribution and structure.

- Bottleneck

-

A transient reduction in the abundance of a population. This could occur, for example, because of environmental catastrophe or after the founding of a new population.

- Pleistocene

-

An epoch of the Quaternary period beginning 1.8 million years ago and transitioning to the Holocene epoch approximately 10,000 years ago. The Pleistocene is characterized by a cool climate and extensive glaciation of northern latitudes.

- Population phylogeny

-

The hierarchical relationship among individual populations, typically inferred from pairwise genetic differences between populations.

- Summary statistics

-

Statistics that describe some aspect of polymorphism data, such as the number of polymorphic sites, the distribution of mutation frequencies or the extent of association between linked polymorphisms. Summary statistics are often estimates of parameters in an evolutionary model.

- Coalescent approach

-

A probabilistic construct that describes the hierarchical common ancestry of a sample of gene copies. The probability that two gene copies share a common ancestor (or coalesce) in the preceding generation is proportional to the reciprocal of the size of the entire population.

- Haplotype

-

A contiguous DNA sequence of arbitrary length along a chromosome that has a primary structure that is distinct from that of other homologous regions in a given population.

- Place of the most recent common ancestor

-

The geographical area, of arbitrary scale, where the ancestry of a current sample of gene copies can be traced back to a single, endemic ancestral population.

- Derived

-

The state of genotypic or phenotypic character, possessed by some biological entity, which has mutated from a common ancestral state.

- Paraphyletic

-

When the common ancestor of one natural group is shared with any other such group.

- Time to the most recent common ancestor

-

The number of generations back in time when a single gene copy gave rise to all of the gene copies in a contemporary sample. If n gene copies are sampled from a population of size N, the time to a most recent common ancestor for an autosomal locus is expected to be 4N(1 − 1/n) generations.

- Effective population size

-

The number of individuals of a given generation that contribute gametes to the subsequent generations. This abstract quantity depends on the breeding sex ratio, number of offspring per individual and type of mating system.

- Island model of population structure

-

A commonly used model to describe gene flow in a subdivided population in which each subpopulation of constant size, N, receives and gives migrants to each of the other subpopulations at the same rate, m. Under the Island model, FST = 1/(4Nm + 1).

- Standard neutral model

-

A population genetics model that assumes all individuals in a population are replaced by their offspring each generation, so that the population size remains constant, mating occurs randomly and each parent produces a Poisson-distributed number of offspring. Under these conditions, the model predicts the fate of mutations that are not affected by natural selection.

- Harmonic mean

-

One method for calculating an average, defined as the reciprocal of the arithmetic mean of the reciprocals of a specified set of positive numbers.

- Tajima's D

-

A statistic used to test the standard neutral model for a given region of DNA sequence. It is the standardized difference between the number of pairwise nucleotide differences and the total number of segregating sites.

- Frequency spectrum

-

The distribution of polymorphism frequencies in a sample of DNA sequences. For example, 30% of polymorphisms might occur in a single gene copy, 20% in two gene copies, and so on. Under the standard neutral model, the frequency spectrum is expected to follow a geometric distribution.

- Linkage disequilibrium

-

The non-random association of polymorphisms at two linked loci. Linkage disequilibrium is created by mutation, but broken down over time primarily by crossing over between the two loci.

- Directional selection

-

A form of positive selection in which a single mutation has a selective advantage over all other mutations, resulting in the selected mutation rapidly reaching fixation (that is, a frequency of 100%) in the population.

- Balancing selection

-

A form of positive selection that maintains polymorphism in the population. One well-known form of balancing selection is heterozygote advantage, where an individual who is heterozygous at a selected locus has a higher fitness than either of the homozygous genotypes.

- Population structure

-

Arises when the individual members of a population do not mate at random with respect to geography, age class, language, culture or some other defining characteristic.

- Likelihood-based method

-

A class of statistical methods that calculate the probability of the observed data under varying hypotheses, in order to estimate model parameters that best explain the observed data and determine the relative strengths of alternative hypotheses.

- Bayesian technique

-

An approach to inference in which probability distributions of model parameters represent both what we believe about the distributions before looking at data and the likelihood of the parameters given the observed data.

- Markov chain Monte Carlo technique

-

A simulation technique for producing samples from an unknown probability distribution. By evaluating the probability of the observed data at each step in the Markov chain, an estimate of the probability distribution of model parameters can be obtained by observing the behaviour of the chain as it proceeds through many steps.

- Importance sampling

-

An efficient simulation method for integrating an unknown function, in which only those parameters that can actually produce the observed data are considered.

- Approximate likelihood

-

A measure of the fit of some hypothetical model to a statistic calculated from observed data. For example, if 50% of polymorphisms occur in single individual chromosomes, a population growth model might have a higher likelihood of producing the observed number of singleton mutations than a model of population reduction.

- Deme

-

A geographically localized population of a species that can be considered a distinct, interbreeding unit.

- Neolithic

-

A human cultural period, beginning approximately 10,000 years ago, marked by the appearance in the archaeological record of industries such as polished stone and metal tools, pottery, animal domestication and agriculture.

- Panmictic

-

Describes a diploid population in which each individual of a particular sex has an equal chance of producing offspring with any other member of the opposite sex in the population.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garrigan, D., Hammer, M. Reconstructing human origins in the genomic era. Nat Rev Genet 7, 669–680 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1941

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1941

This article is cited by

-

African mitochondrial haplogroup L7: a 100,000-year-old maternal human lineage discovered through reassessment and new sequencing

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Whole-genome sequence analysis of a Pan African set of samples reveals archaic gene flow from an extinct basal population of modern humans into sub-Saharan populations

Genome Biology (2019)

-

Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018)

-

Interleukin-37 gene variants segregated anciently coexist during hominid evolution

European Journal of Human Genetics (2015)

-

Exploring population size changes using SNP frequency spectra

Nature Genetics (2015)