Key Points

-

The human Y chromosome is male-sex-determining and haploid, and so escapes recombination for most of its length. Haplotypes, which can be defined by the many binary markers and microsatellites that are available, pass down paternal lineages and change only by mutation.

-

A small effective population size and the practice of patrilocality accentuate drift, which leads to the marked geographical differentiation of Y haplotypes. This makes the Y chromosome a powerful tool for investigating events in human genetic history.

-

The study of mutation on the Y chromosome clarifies intra-allelic processes in general, and provides specific information about mutation rates that is useful in estimating the coalescent times of lineages. Intrachromosomal paralogous sequences are plentiful and cause pathogenic and non-pathogenic structural rearrangements.

-

Selection might be important in shaping Y-chromosome diversity in populations, but it has been difficult to identify. Some studies show associations between deleterious phenotypes and particular haplotypes, but these associations are weak; some coalescence times are younger than expected, which indicates recent selection, but these estimates are uncertain, and population phenomena might be an alternative explanation.

-

The phylogeny of binary Y haplogroups is well established, but the dates of branchpoints are uncertain. Many populations have been poorly sampled, and there is ascertainment bias in the set of available binary markers.

-

The recent coalescence time, rooting of the Y phylogeny in Africa and evidence for an 'Out-of-Africa' range expansion, all show that modern Y-chromosome diversity arose recently in Africa and replaced Y chromosomes elsewhere. The pattern of Y-chromosome variation broadly fits a model of a southern migration that reached Australia, and a northern migration into Eurasia.

-

Many features of the patterns of modern Y-chromosome diversity reflect later range expansions and contractions that were driven by changes in climate and lifestyle. Long-term population size, social structures and social selection have also been important.

-

Future developments in the field are likely to include more markers, and a move towards the unbiased resequencing of samples.

-

Other parts of the genome might show a 'haplotype-block' structure that is made up of regions of strong linkage disequilibrium. If this is so, then methods pioneered in the analysis of the Y chromosome could be widely applicable.

Abstract

Until recently, the Y chromosome seemed to fulfil the role of juvenile delinquent among human chromosomes — rich in junk, poor in useful attributes, reluctant to socialize with its neighbours and with an inescapable tendency to degenerate. The availability of the near-complete chromosome sequence, plus many new polymorphisms, a highly resolved phylogeny and insights into its mutation processes, now provide new avenues for investigating human evolution. Y-chromosome research is growing up.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Skaletsky, H. et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome: a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature 423, 825–837 (2003). Analysis and evolutionary interpretation of the near-complete sequence of Y euchromatin, including thorough gene identification.

Bailey, J. A. et al. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 297, 1003–1007 (2002).

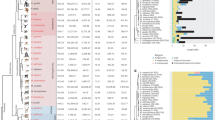

Y Chromosome Consortium. A nomenclature system for the tree of human Y-chromosomal binary haplogroups. Genome Res. 12, 339–348 (2002). A collaborative effort by most of the groups in the field to produce a unified phylogeny and nomenclature, with a built-in updating mechanism, which is becoming widely adopted.

Hammer, M. F. A recent common ancestry for human Y chromosomes. Nature 378, 376–378 (1995).

Thomson, R., Pritchard, J. K., Shen, P., Oefner, P. J. & Feldman, M. W. Recent common ancestry of human Y chromosomes: evidence from DNA sequence data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7360–7365 (2000). The largest study of Y-SNP variation free from ascertainment bias, which is based on DHPLC and proposes a common ancestor ∼59 kya.

Murdock, G. P. Ethnographic Atlas (Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1967).

Burton, M. L., Moore, C. C., Whiting, J. W. M. & Romney, A. K. Regions based on social structure. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 87–123 (1996).

Seielstad, M. T., Minch, E. & Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. Genetic evidence for a higher female migration rate in humans. Nature Genet. 20, 278–280 (1998). This paper proposed that patrilocality, the practice of a wife moving near to the birthplace of her husband after marriage rather than vice versa , could explain most of the excess geographical clustering of Y variants.

Kayser, M. et al. Independent histories of human Y chromosomes from Melanesia and Australia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 173–190 (2001).

Oota, H., Settheetham-Ishida, W., Tiwawech, D., Ishida, T. & Stoneking, M. Human mtDNA and Y-chromosome variation is correlated with matrilocal versus patrilocal residence. Nature Genet. 29, 20–21 (2001). Empirical support for the hypothesis of Seielstad et al . in reference 8.

Nachman, M. W. & Crowell, S. L. Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics 156, 297–304 (2000).

Crow, J. F. The origins, patterns and implications of human spontaneous mutation. Nature Rev. Genet. 1, 40–47 (2000).

Ebersberger, I., Metzler, D., Schwarz, C. & Pääbo, S. Genomewide comparison of DNA sequences between humans and chimpanzees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1490–1497 (2002).

Blanco, P. et al. Divergent outcomes of intra-chromosomal recombination on the human Y chromosome: male infertility and recurrent polymorphism. J. Med. Genet. 37, 752–758 (2000).

Kamp, C., Hirschmann, P., Voss, H., Huellen, K. & Vogt, P. H. Two long homologous retroviral sequence blocks in proximal Yq11 cause AZFa microdeletions as a result of intrachromosomal recombination events. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2563–2572 (2000).

Sun, C. et al. Deletion of azoospermia factor a (AZFa) region of human Y chromosome caused by recombination between HERV15 proviruses. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2291–2296 (2000).

Repping, S. et al. Recombination between palindromes P5 and P1 on the human Y chromosome causes massive deletions and spermatogenic failure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 906–922 (2002).

Kuroda-Kawaguchi, T. et al. The AZFc region of the Y chromosome features massive palindromes and uniform recurrent deletions in infertile men. Nature Genet. 29, 279–286 (2001).

Bosch, E. & Jobling, M. A. Duplications of the AZFa region of the human Y chromosome are mediated by homologous recombination between HERVs and are compatible with male fertility. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 341–347 (2003).

Rozen, S. et al. Abundant gene conversion between arms of massive palindromes in human and ape Y chromosomes. Nature 423, 873–876 (2003).

Heyer, E., Puymirat, J., Dieltjes, P., Bakker, E. & de Knijff, P. Estimating Y chromosome specific microsatellite mutation frequencies using deep rooting pedigrees. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 799–803 (1997).

Kayser, M. et al. Characteristics and frequency of germline mutations at microsatellite loci from the human Y chromosome, as revealed by direct observation in father/son pairs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 1580–1588 (2000). Still the largest published study to measure the mutation rates at Y-chromosomal microsatellites using father–son pairs. This is more laborious than using deep-rooting pedigrees or sperm pools, but produces more reliable measurements.

Carvalho-Silva, D. R., Santos, F. R., Hutz, M. H., Salzano, F. M. & Pena, S. D. J. Divergent human Y-chromosome microsatellite evolution rates. J. Mol. Evol. 49, 204–214 (1999).

Holtkemper, U., Rolf, B., Hohoff, C., Forster, P. & Brinkmann, B. Mutation rates at two human Y-chromosomal microsatellite loci using small pool PCR techniques. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 629–633 (2001).

Jeffreys, A. J., Murray, J. & Neumann, R. High-resolution mapping of crossovers in human sperm defines a minisatellite-associated recombination hotspot. Mol. Cell 2, 267–273 (1998).

Jobling, M. A., Bouzekri, N. & Taylor, P. G. Hypervariable digital DNA codes for human paternal lineages: MVR-PCR at the Y-specific minisatellite, MSY1 (DYF155S1). Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 643–653 (1998).

Jobling, M. A., Heyer, E., Dieltjes, P. & de Knijff, P. Y-chromosome-specific microsatellite mutation rates re-examined using a minisatellite, MSY1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2117–2120 (1999).

Andreassen, R., Lundsted, J. & Olaisen, B. Mutation at minisatellite locus DYF155S1: allele length mutation rate is affected by age of progenitor. Electrophoresis 23, 2377–2383 (2002).

Berta, P. et al. Genetic evidence equating SRY and the testis-determining factor. Nature 348, 448–450 (1990).

Sun, C. et al. An azoospermic man with a de novo point mutation in the Y-chromosomal gene USP9Y. Nature Genet. 23, 429–432 (1999).

Kuroki, Y. et al. Spermatogenic ability is different among males in different Y chromosome lineages. J. Hum. Genet. 44, 289–292 (1999).

Carvalho, C. M. et al. Lack of association between Y chromosome haplogroups and male infertility in Japanese men. Am. J. Med. Genet. 116, 152–158 (2003).

Previderé, C. et al. Y-chromosomal DNA haplotype differences in control and infertile Italian subpopulations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 7, 733–736 (1999).

Jobling, M. A. et al. A selective difference between human Y-chromosomal DNA haplotypes. Curr. Biol. 8, 1391–1394 (1998). The first example of differential selection acting on Y haplogroups, which is supported by a plausible molecular mechanism.

Krausz, C. et al. Identification of a Y chromosome haplogroup associated with reduced sperm counts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1873–1877 (2001).

Raitio, M. et al. Y-chromosomal SNPs in Finno-Ugric-speaking populations analyzed by minisequencing on microarrays. Genome Res. 11, 471–482 (2001).

Paracchini, S., Arredi, B., Chalk, R. & Tyler-Smith, C. Hierarchical high-throughput SNP genotyping of the human Y chromosome using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e27 (2002).

Zerjal, T. et al. The genetic legacy of the Mongols. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 717–721 (2003). Selective expansion of a single Y haplotype, which is explained by a social rather than a biological mechanism.

Pritchard, J. K., Seielstad, M. T., Perez-Lezaun, A. & Feldman, M. W. Population growth of human Y chromosomes: a study of Y chromosome microsatellites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1791–1798 (1999).

Hammer, M. F. & Zegura, S. L. The human Y chromosome haplogroup tree: nomenclature and phylogeny of its major divisions. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 31, 303–321 (2002).

Ingman, M., Kaessmann, H., Paabo, S. & Gyllensten, U. Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature 408, 708–713 (2000).

Kaessmann, H., Heissig, F., von Haeseler, A. & Paabo, S. DNA sequence variation in a non-coding region of low recombination on the human X chromosome. Nature Genet. 22, 78–81 (1999).

Harris, E. E. & Hey, J. X chromosome evidence for ancient human histories. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3320–3324 (1999).

Harding, R. M. et al. Archaic African and Asian lineages in the genetic ancestry of modern humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60, 772–789 (1997).

Tremblay, M. & Vezina, H. New estimates of intergenerational time intervals for the calculation of age and origins of mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 651–658 (2000). Genealogical research in Quebec, Canada, which shows that the male generation time in this population (∼35 years) is longer than the female generation time (∼29 years) and considerably longer than is commonly assumed (20–25 years).

Helgason, A., Hrafnkelsson, B., Gulcher, J. R., Ward, R. & Stefansson, K. A populationwide coalescent analysis of Icelandic matrilineal and patrilineal genealogies: evidence for a faster evolutionary rate of mtDNA lineages than Y chromosomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1370–1389 (2003).

Brunet, M. et al. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature 418, 145–151 (2002).

Jobling, M. A. & Tyler-Smith, C. New uses for new haplotypes: the human Y chromosome, disease, and selection. Trends Genet. 16, 356–362 (2000).

Shen, P. et al. Population genetic implications from sequence variation in four Y chromosome genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7354–7359 (2000).

Hurles, M. E. et al. Native American Y chromosomes in Polynesia: the genetic impact of the Polynesian slave trade. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1282–1287 (2003). This paper shows the importance of taking historical information into account when interpreting genetic data.

Heyerdahl, T. Kontiki: Across the Pacific by Raft (Rand McNally, Chicago, 1950).

Swisher, C. C. et al. Age of the earliest known hominids in Java, Indonesia. Science 263, 1118–1121 (1994).

Gabunia, L. et al. Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science 288, 1019–1025 (2000).

Bermúdez de Castro, J. M. et al. A hominid from the lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: possible ancestor to Neandertals and modern humans. Science 276, 1392–1395 (1997).

White, T. D. et al. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 423, 742–747 (2003).

Valladas, H. et al. Thermoluminescence dating of Mousterian 'proto-Cro-Magnon' remains from Israel and the origin of modern man. Nature 331, 614–616 (1988).

Valladas, H. et al. Thermoluminescence dates for the Neanderthal burial site at Kebara in Israel. Nature 330, 159–160 (1987).

Mellars, P. Archaeology and the origins of modern humans: European and African perspectives. Proc. Brit. Acad. 106, 31–47 (2002).

Hammer, M. F. et al. Out of Africa and back again: nested cladistic analysis of human Y chromosome variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 427–441 (1998). A sophisticated model-based approach to testing hypotheses to explain patterns of global Y diversity.

Cruciani, F. et al. A back migration from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa is supported by high-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome haplotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1197–1214 (2002).

Underhill, P. A. et al. Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations. Nature Genet. 26, 358–361 (2000). This study introduced 160 new binary Y markers and revealed much of the shape of the Y phylogeny and the geographical distribution of lineages.

Bowler, J. M. et al. New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia. Nature 421, 837–840 (2003).

Goebel, T. Pleistocene human colonization of Siberia and peopling of the Americas: an ecological approach. Evol. Anthropol. 8, 208–227 (1999).

Mellars, P. in The Speciation of Modern Homo sapiens (ed. Crow, T. J.) 31–47 (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, UK, 2002).

Redd, A. J. et al. Gene flow from the Indian subcontinent to Australia: evidence from the Y chromosome. Curr. Biol. 12, 673–677 (2002).

Zerjal, T. et al. Genetic relationships of Asians and northern Europeans, revealed by Y-chromosomal DNA analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60, 1174–1183 (1997).

Phillipson, D. W. African Archaeology 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1993).

Rosser, Z. H. et al. Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 1526–1543 (2000).

Semino, O. et al. The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective. Science 290, 1155–1159 (2000).

Bhattacharyya, N. P. et al. Negligible male gene flow across ethnic boundaries in India, revealed by analysis of Y-chromosomal DNA polymorphisms. Genome Res. 9, 711–719 (1999).

Ramana, G. V. et al. Y-chromosome SNP haplotypes suggest evidence of gene flow among caste, tribe, and the migrant Siddi populations of Andhra Pradesh, South India. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 9, 695–700 (2001).

Kivisild, T. et al. The genetic heritage of the earliest settlers persists both in Indian tribal and caste populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 313–332 (2003).

Karafet, T. M. et al. High levels of Y-chromosome differentiation among native Siberian populations and the genetic signature of a boreal hunter–gatherer way of life. Hum. Biol. 74, 761–789 (2002). A good example of what can be done with the present set of markers and analytical tools.

Zerjal, T., Wells, R. S., Yuldasheva, N., Ruzibakiev, R. & Tyler-Smith, C. A genetic landscape reshaped by recent events: Y-chromosomal insights into Central Asia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 466–482 (2002).

Meltzer, D. A. Monte Verde and the Pleistocene peopling of the Americas. Science 276, 754–755 (1997).

Pena, S. D. et al. A major founder Y-chromosome haplotype in Amerindians. Nature Genet. 11, 15–16 (1995).

Underhill, P. A., Jin, L., Zemans, R., Oefner, P. J. & Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. A pre-Columbian Y chromosome-specific transition and its implications for human evolutionary history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 196–200 (1996).

Karafet, T. M. et al. Ancestral Asian source(s) of New World Y-chromosome founder haplotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64, 817–831 (1999).

Lell, J. T. et al. The dual origin and Siberian affinities of Native American Y chromosomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 192–206 (2002).

Tarazona-Santos, E. & Santos, F. R. The peopling of the Americas: a second major migration? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1377–1380 (2002).

Hurles, M. E. et al. European Y-chromosomal lineages in Polynesia: a contrast to the population structure revealed by mitochondrial DNA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 1793–1806 (1998).

Saillard, J., Forster, P., Lynnerup, N., Bandelt, H. -J. & Nørby, S. mtDNA variation among Greenland Eskimos: the edge of the Beringian expansion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 718–726 (2000).

Bosch, E. et al. High level of male-biased Scandinavian admixture in Greenlandic Inuit shown by Y-chromosomal analysis. Hum. Genet. 112, 353–363 (2003).

Alves-Silva, J. et al. The ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA lineages. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 444–461 (2000).

Carvalho-Silva, D. R., Santos, F. R., Rocha, J. & Pena, S. D. J. The phylogeography of Brazilian Y-chromosome lineages. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 281–286 (2001).

Carvajal-Carmona, L. G. et al. Strong Amerind/white sex bias and a possible Sephardic contribution among the founders of a population in northwest Colombia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 1287–1295 (2000).

Roewer, L. et al. Online reference database of Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat (STR) haplotypes. Forens. Sci. Int. 118, 103–111 (2001).

Butler, J. M. et al. A novel multiplex for simultaneous amplification of 20 Y chromosome STR markers. Forensic Sci. Int. 129, 10–24 (2002).

Di Bernardo, G. et al. Enzymatic repair of selected cross-linked homoduplex molecules enhances nuclear gene rescue from Pompeii and Herculaneum remains. Nucl. Acids Res. 30, e16 (2002).

Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002).

Su, B. et al. Y-chromosome evidence for a northward migration of modern humans into Eastern Asia during the last Ice Age. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 1718–1724 (1999).

Karafet, T. et al. Paternal population history of East Asia: sources, patterns, and microevolutionary processes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 615–628 (2001).

Eyre-Walker, A. & Awadalla, P. Does human mtDNA recombine? J. Mol. Evol. 53, 430–435 (2001).

Walzer, S. & Gerald, P. S. A chromosome survey of 13,751 male newborns. in Population Cytogenetics (eds Hook, E. B. & Porter, I. H.) 45–61 (Academic Press, New York, 1977).

Chevret, E. et al. Meiotic behaviour of sex chromosomes investigated by three-colour FISH on 35 142 sperm nuclei from two 47, XYY males. Hum. Genet. 99, 407–412 (1997).

Solari, A. J. & Rey-Valzacchi, G. The prevalence of a YY synaptonemal complex over XY synapsis in an XYY man with exclusive XYY spermatocytes. Chrom. Res. 5, 467–474 (1997).

Pecon-Slattery, J., Sanner-Wachter, L. & O'Brien, S. J. Novel gene conversion between X-Y homologues located in the nonrecombining region of the Y chromosome in Felidae (Mammalia). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5307–5712 (2000).

Cooke, H. J. & Noel, B. Confirmation of Y/autosome translocations using recombinant DNA. Hum. Genet. 50, 39–44 (1979).

Andersson, M. et al. Y;autosome translocations and mosaicism in the aetiology of 45,X maleness: assignment of fertility factor to distal Yq11. Hum. Genet. 79, 2–7 (1988).

Juvaini, A. -M. The History of the World-Conqueror (UNESCO publishing, 1260) (translated in 1997).

Gill, P., Jeffreys, A. J. & Werrett, D. J. Forensic application of DNA 'fingerprints'. Nature 318, 577–579 (1985).

Sibille, I. et al. Y-STR DNA amplification as biological evidence in sexually assaulted female victims with no cytological detection of spermatozoa. Forens. Sci. Int. 125, 212–216 (2002).

Rolf, B., Keil, W., Brinkmann, B., Roewer, L. & Fimmers, R. Paternity testing using Y-STR haplotypes: assigning a probability for paternity in cases of mutations. Int. J. Legal Med. 115, 12–15 (2001).

Kayser, M. et al. Online Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat haplotype reference database (YHRD) for US populations. J. Forens. Sci. 47, 513–519 (2002).

Jobling, M. A. In the name of the father: surnames and genetics. Trends Genet. 17, 353–357 (2001).

Sykes, B. & Irven, C. Surnames and the Y chromosome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 1417–1419 (2000).

Daly, M. J., Rioux, J. D., Schaffner, S. F., Hudson, T. J. & Lander, E. S. High-resolution haplotype structure in the human genome. Nature Genet. 29, 229–232 (2001).

Jeffreys, A. J., Kauppi, L. & Neumann, R. Intensely punctate meiotic recombination in the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex. Nature Genet. 29, 217–222 (2001).

Phillips, M. S. et al. Chromosome-wide distribution of haplotype blocks and the role of recombination hot spots. Nature Genet. 33, 382–387 (2003).

Kauppi, L., Sajantila, A. & Jeffreys, A. J. Recombination hotspots rather than population history dominate linkage disequilibrium in the MHC class II region. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 33–40 (2003).

Santos, F. R., Pandya, A. & Tyler-Smith, C. Reliability of DNA-based sex tests. Nature Genet. 18, 103 (1998).

Semino, O., Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S., Falaschi, F., Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. & Underhill, P. A. Ethiopians and Khoisan share the deepest clades of the human Y-chromosome phylogeny. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 265–268 (2002).

Wells, R. S. et al. The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10244–10249 (2001).

Qian, Y. et al. Multiple origins of Tibetan Y chromosomes. Hum. Genet. 106, 453–454 (2000).

Kayser, M. et al. Reduced Y-chromosome, but not mitochondrial DNA, diversity in human populations from West New Guinea. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 281–302 (2003).

Capelli, C. et al. A predominantly indigenous paternal heritage for the Austronesian-speaking peoples of insular Southeast Asia and Oceania. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 432–443 (2001).

Underhill, P. A. et al. Maori origins, Y-chromosome haplotypes and implications for human history in the Pacific. Hum. Mutat. 17, 271–280 (2001).

Tarazona-Santos, E. et al. Genetic differentiation in South Amerindians is related to environmental and cultural diversity: evidence from the Y chromosome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 1485–1496 (2001).

Thangaraj, K. et al. Genetic affinities of the Andaman islanders, a vanishing human population. Curr. Biol. 13, 86–93 (2003).

Paracchini, S. et al. Y-chromosomal DNA haplotypes in infertile European males carrying Y-microdeletions. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 23, 671–676 (2000).

Quintana-Murci, L. et al. The relationship between Y chromosome DNA haplotypes and Y chromosome deletions leading to male infertility. Hum. Genet. 108, 55–58 (2001).

Paracchini, S. et al. Relationship between Y-chromosomal DNA haplotype and sperm count in Italy. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 25, 993–995 (2002).

Kittles, R. A. et al. Cladistic association analysis of Y chromosome effects on alcohol dependence and related personality traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4204–4209 (1999).

Ellis, J. A., Stebbing, M. & Harrap, S. B. Significant population variation in adult male height associated with the Y chromosome and the aromatase gene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 4147–4150 (2001).

Charchar, F. J. et al. The Y chromosome effect on blood pressure in two European populations. Hypertension 39, 353–356 (2002).

Ellis, J. A., Stebbing, M. & Harrap, S. B. Association of the human Y chromosome with high blood pressure in the general population. Hypertension 36, 731–733 (2000).

Shoji, M. et al. Lack of association between Y chromosome Alu insertion polymorphism and hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 25, 1–3 (2002).

Ewis, A. A. et al. Linkage between prostate cancer incidence and different alleles of the human Y-linked tetranucleotide polymorphism DYS19. J. Med. Invest. 49, 56–60 (2002).

Quintana-Murci, L. et al. Y chromosome haplotypes and testicular cancer in the English population. J. Med. Genet. 40, e20 (2003).

Passarino, G. et al. Y chromosome binary markers to study the high prevalence of males in Sardinian centenarians and the genetic structure of the Sardinian population. Hum. Hered. 52, 136–139 (2001).

Jamain, S. et al. Y chromosome haplogroups in autistic subjects. Mol. Psychiatry 7, 217–219 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Karafet for unpublished information on American populations, the Y Chromosome Consortium for consultation and for allowing us to include figure 3, and M. Hurles, F. Santos and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. M.A.J. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship in Basic Biomedical Science. We apologize to those collegues whose work we could not cite because of limited space.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Related links

Related links

Databases

LocusLink

Further information

Phylogenetic Network Analysis Shareware Software

Y-STR Haplotype Reference Database Asia

Glossary

- SATELLITE DNA

-

A large tandemly-repeated DNA array that spans hundreds of kilobases to megabases.

- RECOMBINATION

-

The formation of a new combination of alleles through meiotic crossing over. Some authors include intrachromosomal gene conversion under this heading. As this has been shown on the Y chromosome, they prefer not to refer to it as 'non-recombining'.

- EUCHROMATIN

-

The part of the genome that is decondensed during interphase, which is transcriptionally active.

- PHYLOGENETIC TREE

-

A diagram that represents the evolutionary relationships between a set of taxa (lineages).

- PARALOGUES

-

Sequences, or genes, that have originated from a common ancestral sequence, or gene, by a duplication event.

- MICROSATELLITE

-

A class of repetitive DNA sequences that are made up of tandemly organized repeats that are 2-8 nucleotides in length. They can be highly polymorphic and are frequently used as molecular markers in population genetics studies.

- HAPLOGROUP

-

A haplotype that is defined by binary markers, which is more stable but less detailed than one defined by microsatellites.

- NRY, NRPY AND MSY

-

Several neologisms have been introduced to refer to the portion of the Y chromosome that excludes the pseudoautosomal regions, for example, non-recombining Y (NRY), non-recombining portion Y (NRPY) and male-specific Y (MSY), but none has achieved wide acceptance.

- EFFECTIVE POPULATION SIZE

-

The size of an idealized population that shows the same amount of genetic drift as the population studied. This is approximately 10,000 individuals for humans, in contrast to the census population size of >6 × 109.

- PARAGROUP

-

A group of haplotypes that contain some, but not all, of the descendants of an ancestral lineage.

- HOMOLOGUES

-

Genes or sequences that share a common ancestor.

- HOMOPLASY

-

The generation of the same sequence state at a locus by independent routes (convergent evolution).

- GENE CONVERSION

-

The non-reciprocal exchange of sequence.

- BALANCING SELECTION

-

Selection that favours more than one allele, for example, through heterozygote advantage, and so maintains polymorphism.

- FREQUENCY-DEPENDENT SELECTION

-

Selection that favours the lower-frequency alleles and so maintains polymorphism.

- XX MALE

-

An individual with a 46,XX karyotype but a male phenotype rather than the expected female phenotype

- PHYLOGEOGRAPHY

-

The analysis of the geographical distributions of the different branches of a phylogeny.

- MULTIFURCATION/BIFURCATION

-

The splitting of an ancestral lineage into two or more daughter lineages.

- HOLOCENE

-

The 'wholly recent' geological period that spans the past ∼11,000 years and is characterized by an unusually warm and stable climate.

- AZOOSPERMIA

-

The absence of sperm in the ejaculate.

- ENDOGAMY

-

The practice of marrying within a social group.

- ΦST

-

A measure of the subdivision between populations that takes into account the molecular distance between haplogroups/haplotypes, as well as their frequency.

- LINKAGE DISEQUILIBRIUM

-

The non-random association between alleles in a population owing to their tendency to be co-inherited.

- HAPLOTYPE BLOCK

-

The apparent haplotypic structure of the recombining portions of the genome, in which sets of consecutive co-inherited alleles are separated by short boundaries; there is debate about the origins of haplotype blocks and whether the boundaries correspond to recombination hotspots.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jobling, M., Tyler-Smith, C. The human Y chromosome: an evolutionary marker comes of age. Nat Rev Genet 4, 598–612 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1124

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1124

This article is cited by

-

Revisiting informed consent in forensic genomics in light of current technologies and the times

International Journal of Legal Medicine (2023)

-

The genetic scenario of Mercheros: an under-represented group within the Iberian Peninsula

BMC Genomics (2021)

-

Y-DNA genetic evidence reveals several different ancient origins in the Brahmin population

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2021)

-

Ancestral genetic legacy of the extant population of Argentina as predicted by autosomal and X-chromosomal DIPs

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2021)

-

Genetic ancestry inferred from autosomal and Y chromosome markers and HLA genotypes in Type 1 Diabetes from an admixed Brazilian population

Scientific Reports (2021)